File - Michael Klein

advertisement

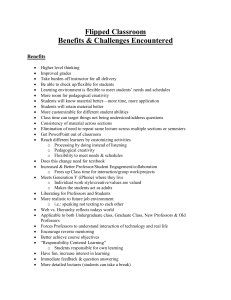

Flipping the Classroom Exploring flipped classrooms in secondary and post-secondary education Michael Klein Spring 2015 With the new fad of flipping the classroom, instructors are hopping on the train and drawing conclusions that are not immediately available. When comparing a flipped and non-flipped classroom, results are not as what expected. It is important to keep in mind other variables that go into a curriculum such as active learning, cooperative learning, constructivism, and peer instruction. Page | 1 Flipping the classroom has been a mainstream trend in educational discussions lately. There are still many questions to be answered about this fad and many more discussions about how to improve the implementation. The flipped classroom simply is not replacing lectures with videos (Bergmann 2014). Learning has to take place in the flipped classroom and when students are in isolation staring at a computer screen of their teacher giving a lecture, it merely is not. Dr. Scot Adams, a University of Minnesota Math Professor, says, “There are two sides to learning: skill training and curiosity. If you do not nurture both, they will die” (Adams 2014). Discovery is crucial to obtaining a deeper understanding of conceptual material and internalizing it. Many students today in college and high school learn enough of the material to pass a final exam and move on to the next topic. In math courses, students who do not absorb concepts get steered away from taking future courses in mathematics. Some may even assume that math is not needed for their degree or for their future (Adams 2014). Math courses can be stimulated by flipping a classroom and by using proper designs to make the material more meaningful and fun for students. The credit of the beginning of the hype is given to two chemistry teachers, Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams, at Woodland Park High School in Colorado. The two teachers were continually spending time re-teaching lessons for students who missed class. After posting lessons online for the students who missed, other students used them for extra review and gave their teachers positive feedback about it. Bergmann and Sams utilized this opportunity to reorganize their class time to be more effective for their students. However, these Woodland Park teachers did more than reshuffle their time. Woodland Park did what most theorists say is the most effective way to implement the flipped classroom, by giving struggling students inspiration and advanced students more freedom to learn independently (Tucker 2012). Salman Page | 2 Kahn says that the teacher is now “liberated to communicate with their students” (Miller 2012). It not only encourages students to interact with each other, but forces teachers to interact with them as well. There are many definitions that spread across the nation. A more general definition is given by Lage et al as “Inverting the classroom means that events that have traditionally taken place inside the classroom now take place outside the classroom and vice versa” (Bishop 2013). That is as general as the definition can get. It does not include any description of how each part of the classroom should be executed. A better definition would be, “An educational technique that consists of two parts: interactive group learning activities inside the classroom, and direct computer based individual instruction outside the classroom.” A flipped classroom is a progression of learning and education, not just a rearrangement (Bishop 2013). There are many other variables that are attributed with flipping a classroom including the pedagogy involved in the design of the curriculum. Constructivism is a pedagogical technique that coincides well with a flipped classroom. Constructivism has to do with building new knowledge based off of previous knowledge. Usually the construction happens when a student is faced with unfamiliar information and uses their prior skills to understand it (Denton 2012). In Denton’s article he brings up some characteristics of constructivism such as facilitation of group dialogue, reference to formal domain knowledge, opportunities for students to select the challenge level, and practice of metacognitive skills. In the flipped classroom, many of these characteristics are brought out by the structure of the course. When students are at home the group dialogue may not be prevalent, but when they are in lecture doing problem solving the communication is somewhat forced. Most of the Page | 3 characteristics are controlled by the instructor, for instance, the problem set and activities should be assembled in a way where students are forced to use skills learned in previous lessons or even past courses. The problems also may need to scaffold which means they could start with a specific problem and then generalize to a larger outcome. Similarly, in order for students to show their metacognitive skills, they will need to be able to not only perform but also explain. In many instances we see students memorize a set of steps and never understand why they are doing a specific problem. Having explanatory problems intertwined in activities helps reassure the students understand concepts clearly and the reasons for learning those concepts. Cooperative learning is another mode of instruction that blends well with a flipped classroom. Cooperative learning is aligned with social interdependence, which means that students must work together in order to complete a problem (Denton 2012). This also forces some of the group dialogue mentioned earlier with constructivism. These two types of instruction are not always associated with a flipped classroom, but are key components to research done on the flipped classroom. There are different types of flipped classrooms and the interaction between students depends on which one is being implemented. The most common type of flipped classroom is called the traditional flipped classroom. This is where most teachers start their flipped classroom experience. It is also the type that best fits the more basic definition given above by Lage et al. Students typically watch the lecture videos at home and then go to class to receive more skill building exercises. This is where students can obtain more engagement from their peers and their teachers (Flipped Classroom). Students are able to get more guidance from their teachers when learning a hard concept. This type fosters more of a “guide on the side” rather than a “sage on the stage” criteria (Miller 2012). Miller also states that this type of flipped classroom must be met with proper instruction. “We Page | 4 must focus on creating the engagement and then look at structures that can support it” (Miller 2012). A second type of flipped classroom is called the flipped mastery. This is the type of classroom that Dr. Mike Weimerskirch, a Contract Assistant Professor and the Lower Division Mathematics Coordinator at the University of Minnesota, implements most in his pre-calculus II course. In a flipped mastery, the students learn at their own pace. Students still watch the lecture videos at home and use class time for practice and skill building, however students must pass an assessment in order to move on to the next objective. If a student does not pass, then they must relearn the material and retry (Flipped Classroom). Weimerskirch has his students take weekly quizzes that they must pass, however Weimerskirch moves on even if all students have not passed the quiz. Although the material keeps moving forward, students still are encouraged to master the previous material first. Weimerskirch (2014) says, “Students are thinking about material where they are at.” They may not understand the material immediately, but when further topics are introduced, students make key connections to past material that enhances their understanding. The peer instruction flipped classroom is another type that teachers are able to implement. This type was started at Harvard and is where students learn the basic material outside of lecture. When the students are in class, they answer key conceptual questions individually about the material. Next, they are attempting to convince their peer of the correct answer. Subsequently, if a student has the wrong answer it is extremely difficult for them to convince their peers of that conclusion (Flipped Classroom). The Peer Assisted Learning (PAL) program at the University of Minnesota could be thought of as a peer instruction flipped classroom. Students in PAL courses have their lectures and learn the material prior to coming to Page | 5 their weekly PAL session. During session, students work in groups and discuss material that they learned in the previous week with their peers. Students are encouraged to collaborate with each other to discuss difficult concepts and work on problems. This is where we see a lot of debate between students about who has the correct answer. Another flipped classroom is the problem based learning flipped classroom in which students explore a project individually and learn through the process. This can be thought of as a learn-as-you-go type of instruction where students may have to learn specific tasks in order to fulfill a part of their project. Once they learn that specific concept, they can continue with their project. An example Byron High School gives is a student building a fuel cell. At a certain point, the student may get stuck on how to balance a chemical equation. They watch a short video on how to perform that task and then continue building their fuel cell (Flipped Classroom). Students get a much more meaningful education through this flipped classroom because of the independence to select their own problem and learn about something that engages their own interests. The last type of flipped class I will talk about is the inquiry flipped classroom. This is similar to the problem based learning flipped classroom where students get to learn something that is more interesting to them. Students start by watching a video on a related topic that engages their interests. Following, students spend class time digging deeper into the material and begin to learn relations between course material and their topic.. If a student has a misunderstanding, they watch more videos to fill those gaps. Once they feel comfortable with the material and feel they have mastered it, they are able to present it to their classmates (Flipped Classroom). Page | 6 Byron, Minnesota is a small town in southern Minnesota near Rochester. Byron High School had a shortage of funds. They had no money to support their classrooms with little funding from the state and a recent $1.2 million budget cut. Byron had to figure out a solution for the lack resources and came up with a way to get the needed new textbooks. They got rid of them. The math department suggested creating their own curriculum by crafting video lessons after the school agreed to unblock YouTube. After years of carrying out the new curriculum, they adopted the flipped classroom in 2011. That same year, they were awarded the Intel High School Mathematics Award (Fulton 2012). Research on the flipped classroom is difficult because one cannot conclude that it was solely the flipped instruction that pertained to increased scores. However, at Byron High School they have seen a 13.6% increase in their calculus scores with a flipped classroom with peer instruction compared to a regular lecture. Similar results were yielded with pre-calculus, advanced algebra, and geometry (Flipped Classroom). Byron has also seen dramatic increases in their math mastery level, which was at 29.9% in 2006 and had risen to 65.6% in 2010. Just one year later when they implemented the flipped classroom, it was at 73.8% (Fulton 2012). Once again, this cannot be concluded to be exclusively from the flipped classroom, but with the integration of other proper techniques of active learning such as constructivism and cooperative learning. It is important to look at what type of instruction is used within the flipped classroom when comparing results between flipped and non-flipped classrooms. Jean McGivney-Burelle and Fei Xue talk about flipping a calculus course at the University of Hartford. In their study, they looked at two sections of the calculus course taught by the same professor. For the first exam, both lectures were taught the same as a traditional style lecture. After the first exam, the professor switched one of the lectures to a flipped Page | 7 classroom and compared results. After the change, they saw a slight increase in exam two scores in the flipped section compared to the traditional section (McGivney-Burelle, Xue 2013). This cannot be fully attributed to the flipping of the lecture, but the techniques used and the fact that the professor had extra time to interact with students rather than lecture at them. We also see similar results in a biology course. At Brigham Young University, a study was done in a biology course with one traditional style lecture and one flipped lecture (Jensen, Kummer, Godoy 2014). Both lectures were taught by the same professor who implemented an active learning approach in both lectures. The 5-E learning cycle: engage, explore, explain, elaborate, evaluate, was used in the study and the results were as follows. Students who were in the flipped lecture “felt that the activities had a more clear purpose for their learning,” however there was also a recurrent complaint about how the technology system used was a hindrance to their enjoyment of the class (Jensen, Kummer, Godoy 2014). Their final result from the study was that it makes no difference as to which style of lecture is used when both implemented an active learning, constructivist approach. This is allimportant to keep in mind when we look at a second semester pre-calculus course at the University of Minnesota. Pre-Calculus II is taught in two different formats at the University of Minnesota. One is flipped and the other is a traditional style lecture. Demographically, the two lectures were near to identical with student enrollment (OUE 2015). Trying to compare the two lecture styles is difficult because of some factors mentioned before. The lectures are taught by two different professors who may have two different styles of teaching. The more important result we want to look at is the enrollment and success in calculus I. From the flipped pre-calculus II course, about 55% enrolled in calculus I with a little more from the traditional lecture at 59% enrolling. The Page | 8 more astonishing result was that while 16% of those traditional pre-calculus II students withdrew from calculus, there was a much higher withdraw rate coming from the flipped pre-calculus students at just under 26% (OUE 2015). There are no direct conclusions for the reasons of this, but I still find it intriguing. It is also unknown whether all students were enrolled in the same section of calculus I or if those who did withdraw were condensed into one section. Of those who did complete calculus I, there was no significant difference in the scores between flipped and traditional pre-calculus II students. In order to get more reliable conclusions, they would need to ensure both flipped and non-flipped pre-calculus II courses were taught by the same professor with the same pedagogical approach. Going further, it would need to be recorded of those taking calculus I, who has taken the flipped pre-calculus II course, who has taken the traditional course, and who tested into calculus I without taking pre-calculus II at the University of Minnesota. The flipped classroom approach is something that gained popularity and is being used across the world by secondary and post-secondary education facilities. Naively we may assume that flipping the classroom will help students better understand course content, but in reality we need to look at many more factors involved other than the layout of the class. The most important factor to take into consideration is the pedagogical approach the instructor implements within the flipped classroom. In the biology course at Brigham Young University, we saw conclusions that the layout was insignificant due to the fact that both the flipped and non-flipped section were taught by the same professor using the same instructional design and results were similar in both sections (Jensen, Kummer, Godoy 2014). We also looked at trends such as Byron High School in Minnesota where we could see the increase in proficiency as a flipped classroom was implemented. However, we cannot conclude that this was solely the flipped classroom and we must take into consideration the other factors involved in that situation such as removal of Page | 9 textbooks and the implementation of peer instructions along with the flipped classroom (Fulton 2012). Looking at Byron High School is inspiring and can still lead to an increase in proficiency. What a flipped classroom can do is create more in class time for students and teachers to implement the other instructional design methods and become more efficient with their time in the classroom. The time and effort to put into the creation of a flipped classroom is immense. Some lessons may not be able to be put into a short video, so specific content may need that face-to-face interaction. Flipped classrooms are useful in a situation where instead of lecturing about the same material repetitively, an instructor could have students watch the video at home and do an activity in class. These videos can be used year after year, but should still be tweaked when necessary to fit students’ needs in the following years. In conclusion, the flipped classroom can be a beneficial layout of a classroom if implemented properly with another pedagogical approach. When comparing a flipped classroom versus a traditional classroom, it is crucial to keep all variables consistent in order to get a proper comparison. The more popular trend should not be whether or not to implement a flipped classroom, but what type of pedagogical approach to use within their classroom. In order to have an effective flipped classroom, instructors should be putting more time into creating an effective instructional design and then work on how to deliver the curriculum. Page | 10 References Adams, Dr. Scot. Personal interview. 5 Nov. 2014. Bergmann, Jon, Jerry Overmyer, and Brett Wilie “The Flipped Class: Myth vs Reality.” The Daily Riff (2014): 1-4. Google Scholar. Web. 29 Oct. 2014. Bishop, Jacob L., and Dr. Matthew A. Verleger. “The Flipped Classroom: A Survey of the Research.” American Society for Engineering Education (2013): Google Scholar. Web. 29 Oct. 2014. Denton, David W. "Enhancing Instruction through Constructivism, Cooperative Learning, and Cloud Computing." TechTrends 56.4 (2012): 34-41. Google Scholar. Web. “Flipped Classroom – Byron High School Mathematics Department.” Flipped Classroom. Web. 5 Nov. 2014. Fulton, Kathleen. “Upside Down and Inside Out: Flip Your Classroom to Improve Student Learning.” Learning and Leading with Technology June/July (2012): 12-17. Google Scholar. Web. 28 Oct. 2014. Jensen, Jamie L., Tyler A. Kummer, and Patricia Godoy. "Improvements from a Flipped Classroom May Simply Be the Fruits of Active Learning." CBE-Life Sciences Education 14.5 (2015): 1-12. Google Scholar. Web. Mcgivney-Burelle, Jean, and Fei Xue. "Flipping Calculus." Primus 23.5 (2013): 477-86. Google Scholar. Web. Miller, Andrew. “Five Best Practices for the Flipped Classroom.” Web blog post. Edutopia. 24 Feb. 2012. Web. 29 Oct. 2014 Office of Undergraduate Education (OUE) Math 1151 Flipped Classroom Study. 25 Feb. 2015. Raw data. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Tucker, Bill. “The Flipped Classroom: Online Instruction at Home Frees Class Time for Learning.” Education Next Winter (2012): 82-83. Google Scholar. Web. 29 Oct. 2014. Weimerskirch, Dr. Mike. Personal interview. 6 Nov. 2014.