negotiators

advertisement

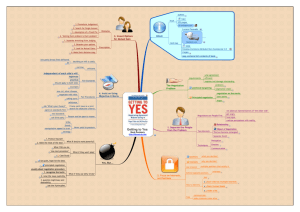

CHAPTER 10 International and Cross-Cultural Negotiation Statements about culture: agree or disagree? 1. When in Rome, do as the Romans do. 2. Cultural stereotypes are a dangerous thing. 3. Business is business all over the world – cultural awareness is not that important. Outline 1. What Makes International Negotiation Different? 2. Conceptualizing Culture and Negotiation. 3. The Influence of Culture on Negotiation. (both the managerial perspectives and the research perspectives ) 4. Culturally Responsive Negotiation Strategies. 1 What makes IB different? (see Phatak and Habib’s (1996) model) Environmental context Immediate context • Political and legal pluralism • Relative bargaining • International economics • Levels of conflict • Foreign governments and bureaucracies • Relationship between negotiators • Instability • Desired outcomes • Ideology • Culture • Immediate stakeholders • External stakeholder power Environmental context FIGURE 10.1 The contexts of IBs Immediate context Legal pluralism Political pluralism External context Relative bargaining power of negotiators and nature of dependence Levels of conflict Immediate stakeholders underlying potential Negotiation negotiations process and Cultural outcomes differences Currency Desired fluctuations and outcome of Relationship between foreign negotiations negotiators before and exchange during negotiation Foreign Govt and bureaucracy Ideological differences Instability and change 1.1 Environmental context • Political and legal pluralism Taxes that an organization pays; Labor codes or standards Different codes of contract law and standards of enforcement Political consideration... • International economics The exchange value of international currencies naturally fluctuates • Foreign governments The extent to the government regulates industries and organizations. 1.1 Environmental context • Instability Lack of resource during business negotiation (paper, electricity, computers); shortage of other goods and service (food, reliable transportation, potable water); and political instability (coups, sudden shifts in government policy, major currency revaluations ) Salacuse (1988) suggests that negotiators facing unstable circumstance should include clauses in their contracts that allow easy cancellation or neutral arbitration, and consider purchasing insurance policies to guarantee contract provisions. Ideology Ideological clashes are manifested at the most fundamental levels about what is being negotiated. Culture (see Box 10.1, Cross-cultural negotiations within the United States, p.277) Deductive or inductive (Salacuse 1988)? Substantive or relational frame? Cultural preference of conflict resolution models External stakeholders Inclusive of business associations, labor unions, embassies, and industry associations, among others, that have an interest or stake in the outcome of the negotiation. 1.2 Immediate context • Relative bargaining power Some contributing factors: The amount of venture (financial and other investment); The management control of the project; The special access to markets; distribution systems or managing government relations. • Levels of conflict Conflict/interdependence Conflict due to ethnicity, identity or geography are more difficult to resolve. 1.2 Immediate context Relationship between negotiators The history of relations (New or old) and the quality of relationship (good or bad). Desired outcomes Some tangible and intangible factors (e.g. the Paris Peace Talks) long-term objectives and short long-term objectives Immediate stakeholders The negotiators themselves and the people they directly represent, such as their managers, employers and boards of directors. 1.3 How do we explain IB outcomes? • No doubt that simple, one-variable arguments are vulnerable. (see Mayer,1992) • e.g. Phatak and Habib’s (1996) model is a good device for guiding our thinking about IB, significantly, multiple factors operating in magnitude over time, and the simultaneous, multiple influences of several factors. 2. Conceptualizing culture and negotiation Four ways to conceptualize culture in IB: 1. Culture as Learned Behavior 2. Culture as Shared Value 3. Culture as Dialectic 4. Culture in Context 2.1 Culture as Learned Behavior This approach to understanding the effect of culture documents the systematic negotiation behavior of people in different cultures. It concentrates on creating a catalog of behavior at foreign negotiators should expect when entering a host culture. 2.2 Culture as Shared Value Understanding central values and norm and then building a model for how these norms and values influence negotiation within that culture. Geert Hofstede (1980a, 1980b,1989,1991)’s cultural dimensions in international business: Individualism/Collectivism; power Distance; career Success/Quality of Life; Uncertainty Avoidance; e.g. Negotiators from low uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to adapt to quickly changing situations and will be less uncomfortable when the rules of the negotiation are ambiguous or shifting. Shalom Schwartz’s 10 cultural values He concentrates on identifying motivational goal underlying cultural values and found 10 values. These 10 values may conflict or be compatible with each other. He also proposed that the 10 values may be represented in two bipolar dimensions: Openness to change/conservatism self-transcendence/self-enhancement Figure10.2 Schwartz’s 10 cultural Values, p.288 Self-transcendence Openness to change Self-direction universalism Benevolence Simulation conformity Hedonism Tradition security Achievement Conservation Self-enhancement Power 2.3 Culture as Dialectic Janosik (1987) recognizes that all cultures contain dimensions or tensions that are called dialectics. Its advantage over the culture-as-shared-values approach lies in that it can explain variations within cultures, suggestive of the need to appreciate the richness of the cultures in which negotiators will be operating. 2.4 Culture in Context Tinsley, Brett, Shapiro, and Okumura(2004) proposed cultural complexity theory in which they suggest that cultural values will have a direct effect on negotiations in some circumstances and a moderated effect in others. The increased complexity of such models ironically suggests its dwindling usefulness; however, their strength is in forging a deeper understanding of how cross-cultural negotiations work and using that understanding to prepare and engage more effectively in IB. 3.The Influence of Culture on Negotiation 3.1 The Managerial Perspectives Table 10.2 summarizes 10 different ways that culture can influence negotiation. (p.291) (TBCed) Table 10.2 Ten Ways That Culture Can Influence Negotiation(p.291) Negotiation Factors Range of Cultural Responses Contract Definition of negotiation Negotiation opportunity Distributive Selection of negotiators Experts Protocol Communication Time sensitivity Risk propensity Groups versus individuals Nature of agreements Emotionalism Informal Relationship Integrative Trust associates Formal Direct Indirect High Low High Low Collectivism Specific High Individualism General Low 3.2 Research Perspectives A conceptual model of where culture may influence negotiation has been developed by Jeanne Brett (2001)(see Figure 10.3, p.295) His model identifies how the culture of both negotiators can influence the setting of priorities and strategies, the identification of the potential for integrative agreement, and the pattern of interaction between negotiators. Figure 10.3 How Culture Affects Negotiation (p.295) Interests and priorities Potential for Integrative agreement Interests and priorities Culture A negotiator Type of agreement Culture B negotiator Strategies Pattern of interaction Strategies Brett (2001)(see Figure 10.3) Brett suggests that cultural values should have strong effect on negotiation interests and priorities, while cultural norms will influence negotiation strategies and the pattern of interaction between negotiators will also be influenced by the psychological processes of negotiators, and culture has an influence on these processes. 4. Culturally Responsive Negotiation Strategies Negotiators should be aware of the effects of cultural differences on negotiation and to take them into account when they negotiate. Stephen Weiss(1994)’s culturally responsive strategies based on the level of familiarity (low, moderate, high) that negotiator has with the other party’s culture. 4.1 Low familiarity Employ Agents or Advisers (Unilateral Strategy) This relationship may range from having the other party conduct the negotiations under supervision (agent) to receiving regular or occasional advice during the negotiation Bring in a Mediator (Joint Strategy) Interpreters will often play this role, providing both parties with more information than the mere translation of words. Mediators may encourage one side or the other to adopt one culture’s approaches or a third culture approach. 4.2 Moderate Familiarity Adapt to the Other’s Approach (Unilateral Strategy) Negotiators make conscious changes in their approach so that it is more appealing to TOS. Rather than trying to act like TOS, they maintain a firm grasp on their own approach but make modification to help relations with TOS Coordinate Adjustment (Joint Strategy) Both parties make mutual adjustments to find a common process for negotiation, which requires a moderate amount of knowledge about TOS’s culture and at least some facility with his or her language. 4.3 High Familiarity Embrace the Other’s Approach (Unilateral Strategy) The negotiator, necessarily bilingual and bicultural, adopts completely the approach of the other negotiator. Improvise an Approach (Joint Strategy) Both need to have high familiarity with TOS’ culture and a strong understanding of the individual characteristics of TOS. Effect Symphony (Joint Strategy) This strategy allows negotiators to create a new approach that may include aspects of either home culture or adopt practices from a third culture. Chapter summary A growing field of exploring the complexities of IB Negotiation • Phatak and Habib(1996)’s model of contributing factors to IB negotiation: both environmental and immediate context • Models of how to understand culture, e.g. Robert Janosik(1987)’s, and how cultural differences to influence negotiations: 10 ways from the practitioner perspective and the effect of culture on negotiation outcomes and process, negotiator cognition and ethics, and conflict resolution. • Stephen Weiss’s 8 different culturally responsive strategies Assignment Reading Task: Gesteland, R. R. (2002). Cross-Cultural Business Behavior. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press. (5e,available) • Francis, June N.P. When In Rome? The Effects of Cultural Adaptation On Intercultural Business Negotiations, Journal of International Business Studies, 1991, V. 22, Iss. 3 • Tinsley, C. H., Curhan, Jenifer J., Kwak, Ro Sung, Adopting a Dual Lens Approach for Examining the Dilemma of Differences in International Business Negotiations, International Negotiation 4: 5–22, 1999. • Debate at the course site “All you got to do is act naturally” VS “When in Rome, do as Romans do”