Project Members

advertisement

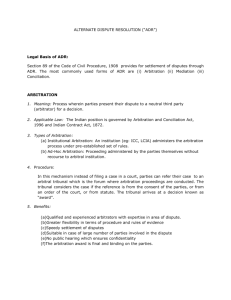

1 2 Project Members Christopher Bloch is a JD candidate with a certificate in international law, graduating in May 2010 from Pace Law School. He completed his undergraduate coursework at Loyola College in Maryland with a degree in political science and minors in marketing and Asian studies. Mr. Bloch taught in the business school of Assumption University in Bangkok, Thailand before coming to Pace Law and has worked during his law school summers at Clayton Utz in Sydney, Australia and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in Cologne, Germany. He is a research assistant at the Pace Institute for International Commercial Law and works as a teacher’s assistant in Contracts, Civil Procedure and Constitutional Law. cbloch@law.pace.edu Rebecca Emory is a JD candidate with a certificate in international law, graduating in May 2010. She completed her undergraduate coursework at George Washington University with a degree in political science. Ms. Emory is a dual citizen of Germany and the United States and spent her law school summers working in Sierra Leone as an intern in the Judicial Chambers of the Special Court of Sierra Leone which tries war criminals from the civil war. She has also done work as a summer associate for Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in Dusseldorf, Germany where she worked in the Corporate Practice Group. remory@law.pace.edu Roberto Pirozzi received his LL.M in Comparative Law with a concentration in International Arbitration from Pace Law School in December 2009 and completed his law degree at LUMSA, University of Rome (2003, summa cum laude). As a qualified Italian attorney since 2006, Mr. Pirozzi worked in Rome as an associate in the Alternative Dispute Resolution Department of Pagani & Partners LLP and a senior associate in the Antitrust Department at Legance LLP. During his time at Pace, Mr. Pirozzi has worked as an intern at Colliern, Halpern, Newberg, Nolletti & Bock LLP in White Plains, NY in their Commercial Litigation Department and spent time as a judicial intern in the chambers of the Honorable Alan D. Scheinkman, New York State Supreme Court, White Plains. rpirozzi@law.pace.edu Leslie Nadelman is a JD candidate at Pace Law School, expecting to graduate in May 2010. She works at the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office, Trial Bureau and is interested in International criminal work. Ms. Nadelman has worked at the Pace Institute for International Commercial Law on several research projects. lnadelman@law.pace.edu 3 Project Aims and Purpose Assess and compare the effectiveness and general use of multi-step arbitration clauses in international commercial contracts through legal research and empirical study focusing on corporate counsel Set forth best practices and model language to be utilized in the application of multi-step ADR clauses based on the survey results 4 Survey Results Survey Results • Arbitration – Definition and Considerations for Their Use • Designating the Substantive Law and Governing Procedures • Enforcing an Arbitral Award Under the New York Convention Survey Results Compelling Compliance • Negotiation – Definition and Considerations for Their Use • Mediation – Definition and Considerations for Their Use • Practical Application Binding Processes • What is a step clause? • Why have step clauses become the norm today according to survey results? • Best Practices for drafting a step clause based on survey Non-Binding Processes Step Clauses Presentation Roadmap • Court Enforcement of Step Clauses • Binding Nature of Clauses on the Parties • Condition Precedent for Steps Survey Results 5 What are Step Clauses? Definition of a step clause Trend towards the use of step clauses Why are step clauses important in international contracts? Single vs. Multi-Step ADR Clauses 18% One Step Multiple Steps 82% 6 Four Basic Questions When are step clauses included? Why are step clauses included? Are step clauses effective compared to standard ADR clauses? What are the essential ingredients in drafting a step clause? Survey Pool Industries Represented in Survey Most survey takers conduct business in North America (43%), Western Europe (23%), and Southeast Asia (15%) with an annual revenue of over $1 Billion (58%) 7 8 Alternative Dispute Resolution Processes Litigation Arbitration Mediation Negotiation Increasing Financial and Relationship Costs Formalities of Arbitration Increase • e.g., discovery procedures Parties Want to Keep Working Relationships Total Contracts Including ADR Clauses 39% 15% 18% 0-25% 11% 9% 25% Contracts Using One Step vs. Multiple Steps 26-50% One Step 51-75% Multiple Steps 76% or more All Contracts 82% 9 Binding Processes as a Last Resort Step clauses are “grounded on the notion that disputes are best resolved by relatively informal, flexible, efficient and inexpensive means, and that binding adjudication through arbitration or litigation should be reserved as a final step in the event all else fails.” -Thomas Stipanowich, T A P (2007) HE RBITRATION ENUMBRA Resolved Through Negotiations Resolved Through Mediation 59% 60% 50% 50% 40% 40% 30% 20% 48% 9% 14% 25% 30% 18% 19% 10% 8% 10% 0% 0-25% 26-50% Series1 20% 51-75% 76% or more 0% 0-25% 26-50% 51-75% 76% or more 10 “Plug and Play” Drafting Since a procedure that may be appropriate for one dispute may not be suitable for another, in the event that parties can reasonably anticipate disputes between them, their goal should be to manipulate boilerplate or model clauses to fit their individual needs. • Boilerplate clauses should not be inserted directly into contracts, or else they could leave major gaps or lead to ambiguities in the application of such clauses in specific agreements 11 Basic Elements Necessary for a Valid Step Clause Order of steps which must be followed Desired rules and limitations placed on each step Indication of time limits for each step (triggering the following step) Specifying an undisputable trigger for the tolling of such time limits Who must be notified when the step has been completed or moot How and when this notification should be completed 12 Mandatory Negotiation Step Generally, negotiation is more practical for settlement when the parties' need to continue the business relationship outweighs their need to get their way on a particular issue. Successful Resolution Using Negotiation 13 Benefits of Mandatory Negotiations 14 Parties that include a mandatory negotiation step generally name the following reasons: Enhances working relationships (64%) High percentage of successful resolutions at this step (58%) Cost-efficiency (58%) Less formal (45%) Provides a better understanding of client needs (39%) Client requests it (17%) Other (e.g., the need or desire to encourage mid-level managers to resolve issues at this level on their own) (5%) Pursuing Negotiation Regardless of Contract Language If the language does not specifically say that the negotiation is mandatory, parties are not required to enter settlement negotiations at all Parties Negotiating Without the Requirement 15 The Mandatory Mediation Step “Mediation is the intervention of an acceptable, neutral, third party with no binding decision-making authority, who assists the parties involved in the dispute to reach a mutually acceptable settlement of the issue in dispute.” Christopher W. Moore, THE MEDIATION PROCESS: PRACTICAL STRATEGIES FOR RESOLVING CONFLICTS (2003) Mandatory Mediation Step in ADR Clauses 16 Requirements for a Mandatory Mediation Step For any mediation step to be considered mandatory, there are certain requirements that should be included in that portion of a step clause: I. II. III. IV. Reasonable transition from negotiation to mediation; Any party or parties to a dispute may initiate mediation by making a request for mediation; Scope of the disputes intended to be submitted to mediation; and Any desired rules discussed in the following slides 17 18 Successful Resolution in Mediation Although a mere 25% of respondents experience the successful resolution of disputes more than 75% in the use of mediation, several benefits are associated with the use of mandatory mediation in ADR clause, as it will be shown in the next slide Successful Resolution Using Mediation 19 Benefits of a Mandatory Mediation Step Some of these benefits (and percent of results) include: • • • • • • Non-binding, but more structured than negotiation (30%) Third-party neutral involvement (26%) High percentage of successful settlements at this step (23%) Enhances working relationships (21%) Institutional support (13%) Cost-efficiency (3%) Allocation of Mediation Costs Of those surveyed 54% equally share mediation costs, regardless of resolution 20 Post-Dispute Mediation Agreement If parties do not include a mediation agreement in their ADR clause but still want to use a mediation institution to resolve an existing dispute, they can enter into the following submission: Post-dispute agreements are not the norm: •If parties want to mediate, they are advised to include mandatory language in their ADR clause •Current perceptions Post-Dispute Agreements to Mediate 21 22 The Binding Processes Pre-adversarial processes may not result in a complete and final resolution of the dispute: • Because of that possibility, it is necessary to include a binding process that will finally resolve any outstanding issues • 60% of parties will use arbitration rather than litigation to finally resolve any outstanding disputes Finishing with Binding Processes There are considerations to be taken into account in favor of both processes as shown in the following slide 23 Arbitration Preference Avoidance of courts (39%) Time-efficiency (35%) Cost-efficiency (34%) Flexibility and Adaptability (31%) Litigation Preference Established precedent (20%) Procedural Familiarity (17%) Codified rules of evidence (15%) Substantive Appeals (15%) Ad Hoc v. Institutional Arbitration One of the most basic decisions in an arbitration clause • 84 % prefer Institutional arbitration over ad hoc • Common institutions named in the survey American Arbitration Association, International Chamber of Commerce, London Court of International Arbitration) 24 Ad Hoc v. Institutional Arbitration Ad Hoc: The arbitration agreement might simply state that "disputes between the parties will be arbitrated", and if the place of arbitration is designated, that will suffice. This approach would leave all unresolved problems (e.g., appointment of the tribunal and how the proceedings will be conducted) to be determined by the law of the "seat" of the arbitration. This approach will work only if the arbitral seat has an established arbitration law. However, if the parties, at any time in the course of an ad hoc proceeding, decide to engage an institutional provider to administer the arbitration, they are able to do so by mutual agreement. 25 Ad Hoc Arbitration Ad hoc arbitration is managed by the parties and by the arbitrators (once appointed) without the assistance of an administering institution It requires the parties to make their own arrangements for the selection of arbitrators and the designation of rules, applicable law, procedures and administrative support In some ad hoc arbitrations, an institutional presence may not be entirely absent – since the parties may designate an established set of rules even without an administering institution and may also designate an institution to act as an appointing authority for the arbitral tribunal in the event that the parties are unable to agree upon tribunal by themselves 26 Benefits of Ad Hoc Arbitration Ad hoc arbitration places more of a burden on the tribunal, and to a lesser extent upon the parties, to organize and administer the arbitration in an effective manner. The primary advantage of ad hoc arbitration is flexibility, which enables the parties to decide upon the dispute resolution procedure A distinct disadvantage of the ad hoc approach is that its effectiveness may be dependent upon the willingness of the parties to agree upon procedures at a time when they are already in dispute 27 Institutional Arbitration An institutional arbitration involves a specialized institution that intervenes, not to arbitrate the dispute, but to assume the functions of administering the arbitral process When naming an arbitral institution at the contract stage, certain factors should be taken into account: I. Nature of the dispute (institutional expertise and connection to various industries) II. Value of the dispute III. Institutional rules (whether they are in line with current practice) IV. Reputation of the institution V. Location VI. Type of Arbitrators 28 Advantages of Institutional Arbitration Some advantages of institutional arbitration and percent of responses: • • • • • • • • • • Established procedural rules (46%) Expertise in arbitration (42%) Assistance in the appointment of arbitrators (37%) Institutional reputation (33%) List of qualified arbitrators (27%) Cost-efficiency (21%) Time-efficiency (19%) Case management services (18%) Aid in the enforcement of the award (13%) Other (e.g., physical facilities) (2%) Cost Myth – Ad Hoc arbitration is not always cheaper because there are no institutional fees 29 Allocation of Arbitration Costs Another consideration to be taken into account when using either institutional or ad hoc arbitration is the allocation of arbitral costs Allocation of Arbitration Costs (Institutional or Ad Hoc) Note: Most institutional rules have a default rule in place giving the arbitrator complete discretion to allocate costs 30 Designating Substantive Law The substantive law is that which governs the substantive rights and obligations of the parties, presenting a significant step in the drafting of any dispute resolution clause. Parties should be aware that they are able to designate different laws to apply to the: • Governing the performance of the contract • Governing the dispute • Governing the procedure of the arbitration Percentage of Parties Designating Governing Law 31 Additional Considerations in Drafting the Arbitration Provision of an Step Clause 32 COMPELLING COMPLIANCE WITH STEP CLAUSES “[A] party cannot be required to submit to arbitration any dispute which he has not agreed to submit” AT&T Tech., Inc. v. Commc’n Workers of America While the ultimate goal of ADR clauses is to stay out of court, improper drafting and straying from the process created will result in delays, or worse – litigation Parties should focus on drafting clear and unambiguous terms including the types of disputes covered, the timelines, and any conditions to move forward with the next step 33 34 JURISDICTIONAL OBJECTIONS • Consent is absolutely necessary • Preconditions must be met to show consent • Jurisdiction of the arbitrators is connected to that consent – parties can resolve it in court 41% 59% Court Arbitration 35 EXAMPLE OF JURISDICTIONAL ISSUE Mediation between A (claimant) and B (respondent). Their step clause calls for A’s Chief Operating Officer to attend the mediation. On the day of mediation, the COO cannot attend due to an emergency Board of Directors’ meeting. COO sends a replacement. The mediation takes place and no resolution is arrived at, so A files a claim at the AAA for arbitration. • Does B have to go to arbitration? • What can B do? 36 COURT REQUIREMENTS FOR COMPULSION Nature of the Dispute • Compulsion only for disputes expressly agreed to Binding Nature • If there are any options or ambiguities in the clause, the court will not find the clause binding Conditions Precedent • Be careful about what preconditions you set, because if they are not met, most courts will not compel the other parties to continue to the next step 37 WAIVER Parties may agree to skip a particular step or waive a condition precedent (e.g., a time limit) jointly • No unilateral waiver or else no jurisdiction Unsettled law, so be careful not to bring the courts in at all – Draft Strong Clauses! 38 Model Clauses • For a breakdown of the common institutional model clauses, please refer to the IACCM Manual distributed with these presentation materials QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS • Thank you for your attention • We will now open up the floor for questions 39