MQS execution essay notes

Explain the factors that eventually led to Elizabeth I’s decision to sign the death warrant of Mary

Queen of Scots in 1587. Evaluate the political and religious consequences of Mary’s execution for

Elizabeth and England between 1587 and 1603.

The candidate’s response to the first part of the essay question could include:

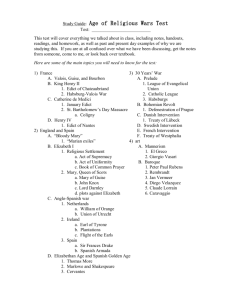

In 1559, Elizabeth returned England to Protestantism, and hoped to embrace Catholics into her

Church Settlement. Under the Act of Uniformity, a shilling fine was levied for each failure to attend church on Sundays and other designated days. A person upholding the Pope as the rightful head of the Church would lose property for the first offence, all goods and liberty for the second offence, and be executed for the third. For the first ten years of Elizabeth ’s reign, this legislation against Catholics was not strictly enforced, and it appears many conformed to the Elizabethan Settlement because it did not threaten them too much. In 1564, a national survey of JPs for the Privy Council r evealed that there were large numbers of ‘Church

Papists’ — Catholic sympathisers who attended Anglican worship to stay clear of trouble, while in the north, Marian priests continued to say Mass with little interference from the authorities. However, Eliza beth’s hope that the advantages of conforming would eventually win over the Catholic laity was to face major challenges during the 19 years of Mary Queen of

Scots’ presence in England.

Mary Queen of Scots’ arrival in England (1568), the Rebellion of the Northern Earls (1569), and the excommunication of Elizabeth by Pope Pius V (1570) signalled a complete change in

Elizabeth’s position. In Catholic eyes, she was now certified a heretic and a usurper. Mary

Queen of Scots was Elizabeth’s cousin and an accessible successor, with (to Catholics) a sounder claim to the throne than Elizabeth. English Catholics were urged to disobey

Elizabeth and actively seek to supplant her. Mary was to become the focus for even further plots and rebellions against Elizabeth.

In 1571, the Ridolfi Plot sought to marry Mary to the Duke of Norfolk and replace Elizabeth as queen. After discovery of the plot, Parliament and most of her Privy Councillors wanted

Elizabeth to execute both Mary and Norfolk. However, Elizabeth believed that executing a divinely appointed legitimate monarch without absolute proof of Mary’s personal involvement in the plot would set a dangerous precedent and give England’s enemies cause to launch a crusade against her. The St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Protestants in France in 1572 made that possibility appear very real.

With the arrival of seminary and Jesuit priests trained at Douai (in the Netherlands), Rheims (in

France), Valladolid (in Spain) and Rome (in Italy), through the 1570s and 1580s, it was clear the Catholic community in England was being given external sustenance and encouragement. The mission of these priests was to prepare the way for the re-conversion of

England once a Catholic regime had been established.

The Papacy actively encouraged rebellion, assassination and foreign conquest. Both King Philip

II of Spain and the Guise party in France were prepared to lend their support to plots to remove Elizabeth and replace her with Mary (Ridolfi 1571, Throckmorton 1583, Parry 1585, and Babington 1586). In these circumstances, harbouring Mary came to seem increasingly like aiding the development of a mortal enemy within. She posed real challenges to the security of the state, Elizabeth’s life and continuance of the established Church.

The assassination of William of Orange (by a Catholic) and the potential for Spanish domination of the Netherlands in 1584 made it clear that England had an important role in ensuring the survival of Protestantism in a European-wide conflict and that the Catholic forces of the

Counter-Reformation were virulent and merciless. Parliament passed the Bond of Association and ordered all Catholic priests to leave the country or be executed.

The outbreak of war with Spain in 1585, Philip II’s preparations for an armada to invade England and the discovery in Mary’s communication of her agreement to the Babington Plot brought unanimous demands for her execution from Elizabeth’s Privy Council and the 1586

Parliament.

Elizabeth did agree to put her on trial for treason at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire.

Mary was found guilty and sentenced to death, but Elizabeth refused to sign the death warrant until February 1587. Even then she refused to let it be sent to Fotheringhay. William

Davidson, her secretary, was persuaded by the Privy Council to release it and Mary was executed on 8 February, passing her claim to Elizabeth’s crown to Philip II of Spain.

The candidate’s response to the second part of the essay question could include:

Immediately, Elizabeth wrote to the young King James VI of Scotland (who was now her heir), apologising for his mother’s death. She refused to speak to Cecil for a month and imprisoned

Davidson. James declaimed his mother’s execution but said he blamed the English Privy

Council rather than Elizabeth and took no further action. Sixteen years later, he inherited the

English throne with Cecil’s son as his chief minister. The execution of Mary had opened up the succession to James and gave Elizabeth a legitimate Protestant heir.

The French protested strongly. However, King Henry III was more worried about the growing power of Spain and the threat of civil war in France. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, England and France were allies.

England and Spain were already at war. Mary’s passing of her claim to the English throne to

Philip II made little difference to his planned invasion of England. The Armada did set sail the following year but was destroyed before it could transfer an army to England’s shores.

Despite the building of further armadas, Philip’s intentions never came to fruition.

However, the consequences for English Catholics who were seen as potential traitors were severe. There were proactive attempts to penalise Roman Catholics through the late 1580s and 1590s. The fortunes of Catholic families diminished. T he Act to retain her Majesty’s

Subjects in their True Obedience made it treason to persuade someone to be a Catholic.

Recusancy fines were increased to £20 a month, with higher fines imposed for hearing or saying Mass. In 1587, recusants defaulting on payment of their fines could have their land seized. The Five Mile Act 1593 required recusants to be confined to within five miles of their homes. These acts of suppression meant that by 1603 there were only about 40 000 Roman

Catholics in England (1% of the population), but may have provoked the Irish Catholic rebellion of the 1590s.

The Act against Jesuit and Seminary Priests meant that Catholic priests failing to leave the country within 40 days were to be executed, and anyone helping or harbouring a priest was liable to suffer death. The Privy Council claimed that the priests were sentenced not for their beliefs but for their implied treason and at their trials all faced the Bloody Question: Whose side would you take if the Bishop of Rome [the Pope] or other prince by his authority should invade the realm? The courage with which execution victims faced their deaths ensured

Catholicism survived. Over the period, about 250 Catholics were put to death or died in captivity, among them 180 priests.

M ary’s execution in 1587 had removed a major internal threat to Elizabeth’s reign. English

Catholics were reluctant to support Spain’s armadas, and there was no further rebellion. Only a tiny minority became involved in plots. Elizabeth’s greatest ally had been the political and largely instinctive loyalty felt by most Catholic gentry towards their monarch. She had the good sense not to jeopardise it. Even in the 1580s and 1590s, those occasionally guilty of recusancy were welcome at court and sat in the House of Lords. It has been calculated that recusancy fines were levied on only 220 people between 1581 and 1593.