2010.scripts - Vanderbilt Business School

advertisement

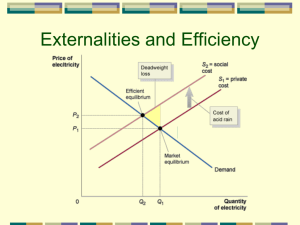

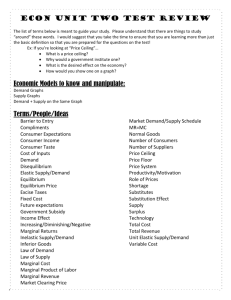

11/28/10 SCRIPTS FOR ONLINE LECTURES TO COMPLEMENT FROEB&MCCANN, MANAGERIAL ECONOMICS CHAPTER 6: SIMPLE PRICING Opening anecdote Background: Consumer Surplus and Demand Curves Marginal Analysis of Pricing Price Elasticity and Marginal Revenue What Makes Demand More Elastic? Forecasting Demand Using Elasticity Stay-Even Analysis, Pricing, and Elasticity Summary & Homework Problems CH 6 Script OUTLINE 1. 2. 3. 4. Intro Demand curves Price elasticity Marginal Analysis of pricing in practice INTRO: This is Luke Froeb at Vanderbilt University. I am the author, along with Brian McCann, of the textbook “Managerial Economics: A Problem Solving Approach.” This lecture is designed to supplement Chapter 6, “Simple Pricing.” When the Soviet Union fell and embraced capitalism, Mars decided to begin selling its popular Snickers candy bar in Russia. They priced it at the same price in rubles as it sold for in England, adjusted for the exchange rate. This was a huge mistake. Since it was the first western-style candy bar sold in Russia, it had no competitors, and there was a huge demand for the product. Distributors purchased all the candy bars for themselves, and then re-sold the candy bar at 2-3 times the recommended retail price. It took Snickers a long time to recognize their mistake, because distributors were reporting sales at the price that Snickers had originally set. Obviously, Mars could have benefited from a better understanding about how to set profitable prices, the topic of this chapter. We begin with the simple case of a firm that owns a single product and sets a single price. Later we will talk about setting prices on multiple, commonly owned products, and about selling a single product at different prices, called “price discrimination.” But before we get there, we have to understand how to price in this simpler case. When choosing price, a firm faces a tradeoff: a higher price means fewer goods sold, but higher margin earned on each sale; while a lower price means more goods sold, but a lower margin on each sale. <<CAN YOU ILLUSTRATE THIS WITH A FIGURE?>> This is an extent decision, and we know from Chapter 4 that marginal analysis tells us how to choose the optimal price. There are two big ideas in this chapter. The first is that we use a demand curve to turn a difficult price decision into easy quantity decision. The question “what price should I charge?” is equivalent to the question “how much quantity should I sell?” Fortunately, we already know how to use marginal analysis to figure this out: If the marginal revenue is bigger than the marginal cost, then sell more. And we do that by reducing price. <<Maybe some kind of moving figures showing that MR>MC means that you should Raise price, and MR<MC means that you should reduce price>> The second big idea of the chapter is that the biggest problem with marginal analysis is measurement. You may have some idea of what your marginal cost is, but figuring out what your marginal revenue is is much more difficult. If you get any information about marginal revenue, it is likely to come in the form of a price elasticity. The more price elastic your demand curve is, the lower the price you should charge. DEMAND CURVES To construct a demand curve, imagine that we have ten consumers, each of whom wants to purchase one unit of a good. We arrange them by their values, by what they are willing to pay for the item. Imagine that the first consumer is willing to pay $10, the second consumer $9, the third consumer $8, and so on. The tenth consumer is willing to pay only $1. So if we charge a price of $10, only one consumer buys; but if we reduce the price to $9, two consumers buy (both the consumer with the $10 value and the consumer with the $9 value). If we lower price all the way down to $1, all ten consumers purchase. This is a demand curve. It describes the behavior of this group of consumers, and tells you how much you will sell if you charge a particular price. Now let’s show you how to use the demand curve to turn the pricing decision into a quantity decision. In the Table below, we show the demand curve in the first two columns. For each price, the demand curve tells us how much we will sell. Price $10 $9 $8 $7 $6 $5 $4 $3 $2 $1 Quantiity Revenue MR MC Profit 1 $10 $10 $3.50 $6.50 2 $18 $8 $3.50 $11.00 3 $24 $6 $3.50 $13.50 4 $28 $4 $3.50 $14.00 5 $30 $2 $3.50 $12.50 6 $30 $0 $3.50 $9.00 7 $28 ($2) $3.50 $3.50 8 $24 ($4) $3.50 -$4.00 9 $18 ($6) $3.50 -$13.50 10 $10 ($8) $3.50 -$25.00 <<IN THE TEXT THAT FOLLOWS, CAN YOU HIGHLIGHT THE CELLS IN THE TABLE THAT CORRESPOND TO THE FIGURES AS I SAY THEM.>> At a price of $10, we sell only one unit, for a revenue of $10. The “extra” or marginal revenue we get from selling the first unit is $10, which is bigger than the marginal cost of $3.50, so we sell the first unit. Then we ask, “should we sell another unit?” We do this by reducing the price to $9. The revenue is $18, and the marginal or extra revenue from selling the second unit is $8. This is still greater than the marginal cost, so we sell the second unit. To sell the third unit, we have to reduce price to $8, for a revenue of $24 and a marginal revenue of $6. This is still bigger than the marginal cost of producing the third unit, so we make the sale. To sell the fourth unit, we have to reduce price to $7, for a revenue of $28 and a marginal revenue of $4. This is still bigger than the marginal cost of $3.50, so we sell the fourth unit. To sell the fifth unit, we have to reduce price to $6, for a revenue of $30 and a marginal revenue of only $2. This is below the marginal cost of $3.50, so we do NOT sell the fifth unit. The optimal price is $7, and in the last column, we see that profit is maximized at this price. There are three things to take away from this analysis. First, the demand curve allowed us to turn a difficult pricing problem into a simple quantity problem that we know how to solve using marginal analysis. Second, note that the marginal revenue is always LESS than the price. At the optimum output of four, price is bigger than marginal cost. So while it might appear that you could gain $7 by selling one more unit, and this is bigger than the marginal cost of $3.50, that would be wrong. You can sell more ONLY by reducing price. The relevant benefits and costs of an extent decision are the marginal revenue and marginal cost, NOT the price. <<MOVING DOWN THE ROW HIGHLIGHTING THE FALLING MARGINAL REVENUE IN THE TABLE ABOVE.>> Third, note that marginal revenue falls as we sell more. This is a critical feature of demand curves. It is similar to the idea that marginal costs increase as we sell more. You pick the low hanging fruit first, and then move on to the higher hanging fruit which is more costly to harvest. Similarly, you make the easy sales first, to the high value customers, but to sell more you have to reduce price. This results in a falling marginal revenue curve -- as you sell more, the extra revenue that you earn on each sale falls. PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND After using a demand curve to show you how to price optimally, I feel a little guilty for telling you that you will never “see” a demand curve. They are very difficult to estimate, especially with the kind of precision that might be useful to someone facing a pricing decision. You can see only the current price and the current quantity, but not the rest of the demand curve. Fortunately, you don’t need to know much in order to figure out whether price is too high or too low. All you need to know are the marginal cost and the marginal revenue at the current output level. If MR>MC, then sell more, and you do this by reducing price. If MR<MC, then sell less, and you do this by raising price. As in Chapter 4, marginal analysis tells you which direction to go, but not how far to go. Still, marginal revenue is hard to measure. If you get some information about marginal revenue, it is likely to be in the form of a price elasticity. Price Elasticity = e = %∆Q ÷ %∆P Price elasticity measures how sensitive consumers are to price. The more price elastic they are, the more they react to price changes. So for example, if price goes up by 5%, and Quantity goes down by 10%, the price elasticity of demand is e=-2. In this case we say that demand is “price elastic” or simply “elastic” because |e|>1. In other words, quantity changes more than price. For an Inelastic demand, one where |e|<1, quantity changes less than price. Marginal revenue is related to price with the simple formula, MR=P(1-1/|e|). Note that this relationship holds only for an elastic demand. We can plug this formula into our marginal calculus to derive the following equivalent relationships: MR>MC P(1-1/|e|)>MC (P-MC)/P > 1/|e| I call the left side of this equation the “actual mark-up” and the right side of the equation the “desired markup.” MR>MC if and only if the actual markup is greater than the desired markup. And we know from above that if MR>MC, we should sell more, and we do this by reducing price. A numerical example, can easily illustrate this idea. If Price is $10, MC is $8, and elasticity is -2, then the actual markup is 80%, but the desired markup is only 50%. In this case, MR>MC, so reduce price. Note that this equation tells us that the price if we could somehow make our demand less elastic, we could raise price. This makes intuitive sense. If our consumers are less sensitive to price, then we can profitably raise price. In chapter 10, we will show you that this is the logic behind what is called a “product differentiation strategy.” If a firm can do something unique, creative, innovative or different to reduce the elasticity of demand, then they can command a higher price. One example is Whole Foods. They sell food in the “Premium, Natural, and Organic” segment, and give 5% of their profit to socially responsible causes. This gives them a less elastic demand curve, the consequence of which is that they can command the highest markup in the grocery industry. MARGINAL ANALYSIS OF PRICING IN PRACTICE: Even information on price elasticity is difficult to come by so you are probably going to have to do something else. Here is an example of how you might use marginal analysis in practice. Imagine that you are working for John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods, and he asks you whether he ought to raise price by 5% on all the products sold at Whole Foods. It is obvious that Whole Foods sells an entire range of products, and that the elasticity for the demand curve facing the entire store would be very difficult to estimate. But let’s imagine that everyone who comes to Whole foods buys a similar “basket” of goods, and let’s try to figure out if a 5% price increase on the basket would be profitable. To do this we can use a version of “break even” analysis. We could ask “how much quantity could we afford to lose and still break even?” This is sometimes called the ‘stay even” quantity or “critical loss.” It can be computed as Critical Loss= %∆Q = %∆P/(%∆P+Markup) where the Markup=(P-MC)/P. If we lose less than the critical loss, then the price increase is profitable, but if we lose more, then it is not. For example, if the markup at Whole Foods is 40%, then the Critical Loss= 5%/(5%+40%)=11.1%. So how do we determine whether Whole Foods would lose more than the critical loss? An economist working on behalf of Whole Foods read marketing studies and found that most people who shop at Whole Foods also shop at another grocery store, like Kroger or Safeway. Since these stories carry many of the same items that Whole Foods does, the economist concluded that the shoppers could easily many of their purchases if Whole Foods raised price. He concluded that the price increase would not be profitable because demand for Whole Foods is very elastic. This is equivalent to the marginal analysis of pricing mentioned above, but it is done with two simple steps. First you calculate the break even quantity, and second, you study demand to determine whether you would lose more than the break even quantity. CHAPTER 7: ECONOMIES OF SCALE AND SCOPE Opening anecdote Increasing Marginal Cost Economies of Scale Learning Curves Economies of Scope Diseconomies of Scope Summary & Homework Problems OUTLINE: 1. ANECDOTE ABOUT BRUCE HENDERSON AND LOCKHEED TRI STAR 2. BIG IDEA IS THAT THE SIMPLE COST FUNCTION WITH A FIXED COST TO ENTER AND A CONSTANT MARGINAL COST OF PRODUCTION IS SUFFICIENT FOR MOST DECISIONS BUT NOT ALWAYS. SOMETIMES, YOU NEED MORE. 3. INCREASING MC: STORY ABOUT SONY 4. ECONOMIES OF SCALE: STORY ABOUT OFFICE SUPERSTORES AND MERGER OF TWO SUPPLIERS OF COMB BINDING EQUIPMENT 5. RETURN TO BRUCE HENDERSON 6. STORY OF PET FOOD CHAPTER 8: UNDERSTANDING MARKETS AND INDUSTRY CHANGES Opening anecdote Which Industry or Market? Shifts in Demand Shifts in Supply Market Equilibrium Predicting Industry Changes Using Supply and Demand Explaining Industry Changes Using Supply and Demand Prices Convey Valuable Information Market Making Summary & Homework Problems OUTLINE FOR SCRIPT 1. Opening Anecdote: Cash for clunkers: Looks like a good deal but don’t realize that price of new cars will increase, and price of old cars will increase, so the changes doesn’t look near as good. 2. In this chapter we show you how to analyze changes that occur at the industry or “market” level. a. Different from MR=MC pricing as that concerned a single monopolist and a demand curve; whereas this is applicable only for a group of sellers competing to sell and a group of buyers competing to buy. So do NOT use this to say something about the supply and demand for iPads, as this analysis does not apply to single products. You can use this to say something about the demand and supply of mobile reading tablets. b. Before you start, define the market: product and geographic dimensions c. This analysis is particularly useful for firms whose fortunes are tied closely to the fortunes of the industry in which they operate. 3. Supply curves are constructed similarly to demand curves. But instead of lining up buyers by their top dollar values, we line up sellers by their bottom line costs. In contrast to demand curves, where high prices mean that fewer buyers are willing to buy, high prices mean that more sellers are willing to sell. a. Market equilibrium occurs when the number of sellers equals the number of buyers. b. No such thing as a shortage—unless prices cannot adjust. 4. We use demand and supply curves to answer two types of questions: how can I predict changes in this industry: and how do I explain past movements of price and quantity at the industry level. 5. We begin with the prediction problem associated with the cash for clunkers program. It was a subsidy paid by the government tied to the purchase of a new low-mileage car and the destruction of an old high-mileage car. a. Lets begin by examining the monthly market for new low-mileage cars in the united states. <<DRAW DEMAND CURVE SHIFTING RIGHT, DRAW AN ARROW SHOWING PRICE AND QUANTITY INCREASING>> We can see in the graph below that the demand curve shifted to the right, or increased, which increased the price and quantity of new cars. b. But then what happened after the program ended? It is likely that some of the demand increase for August was demand that would have been ordinarily occurred in September, so when September finally gets here, demand goes down below it would have ordinarily been. As a result, <<DRAW DEMAND CURVE SHIFTING BACK DOWN BELOW WHERE IT WAS ORIGINALY. SHOW THE PRICE AND QUANTITY GOING BACK DOWN BELOW WHERE IT WAS ORIGINALLY>> In fact, if we look at the monthly sales data for US cars, this is exactly what we see. <<SHOW TIME SERIES GRAPH OF MONTHLY CAR SALES SHOWING>> The demand increase in July and August was mainly “stolen” from September. In other words, the program served mainly to accelerate sales that would have occurred in September by a couple of months, and there was no long run, or permanent effect of the stimulus. Now we turn our attention to the monthly used high mileage car market. What happened here? Predictably, when you destroy 5 million used cars, supply of used cars for sale decreases, and this pushed prices of used cars higher. <<DRAW GRAPH SHOWING A SUPPLY DECREASE WITH THE PRICE GOING UP AND THE QUANTITY GOING DOWN>> The used car models jumping the most in price include mid-size SUVs and minivans designed to carry around families. Used Cadillac Escalades are almost 36% more; Chevy Suburbans and Dodge Grand Caravans jumped 34% in price; a. BMW X5 is 33% higher; and an Acura MDX will run you 29% more. Those of you who are thinking ahead, might realize that demand for the used car market would go down because the cash for clunkers subsidy has made it more attractive to buy new cars. But this effect must have been small because we see that the price has fallen. And this highlights another feature of this kind of modeling: you use this to isolate the big effects that cause price and quantity to change. Your model is useful only in so far as it Now put yourself in the place of the owner of one of these cars, contemplating trading it in to qualify for the Cash for Clunkers program. You do the profit calculus, and figure out that the trade in will be a good deal, because the program pays you more for your used car ($3000) than you can get by selling it or trading it in to the dealer. HOWEVER, unless you explicitly took account the higher opportunity cost of your used car caused by the decrease in supply the higher price of the new cars caused by the increase in demand, you might have made an unprofitable decision. 6. The second thing we want you to do is to be able to explain past price and quantity movements. For example, suppose I tell you that in the past two years, quantity of smart phones has increased while price has fallen. What explains this? <<INSERT GRAPH OF SUPPLY INCREASE, AND AN ARROW BETWEEN INITIAL PRICE AND QUANTITY AND FINAL PRICE AND QUANTITY>> The only explanation is that supply has increased because the costs of producing smart phones has gone down. 7. Similarly, if I tell you htat price has increased, and quantity has increased, the only explanation is an increase in demand. <<INSERT graph showing chae>> a. Demand and supply analysis is part of the business vernacular, and you have to learn it and be able to articulate it quickly and clearly. More than any other analytical skill, this is likely to come up in interviews, as the interviewer brings up a current “fact” in the news, and asks you to explain it. For example, an interviewer might ask you why long term interest rates are going down. If you think of the demand and supply of loans, and the interest rate as the “price” of a loan, then an increase in the supply of loans (as when the federal reserve prints money and makes loans by buying bonds) would explain this. CHAPTER 9: RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN INDUSTRIES: THE FORCES MOVING US TOWARDS LONG-RUN EQUILIBRIUM Opening anecdote Competitive Industries The Indifference Principle Monopoly Summary & Homework Problems CHAPTER 10: STRATEGY, THE QUEST TO SLOW PROFIT EROSION (NOTE THIS IS A NEW CHAPTER BASED ON SPLITTING OLD CHAPTER 9 AND EXPANDING) Opening anecdote Strategy—The Quest to Slow Profit Erosion Strategy is Simple Sources of Economic Profit The Three Basic Strategies Summary & Homework Problems CHAPTER 11: USING SUPPLY AND DEMAND: TRADE, BUBBLES, MARKET MAKING (NOTE THIS IS A NEW CHAPTER BASED ON SPLITTING OLD CHAPTER 8 AND EXPANDING) Opening anecdote The Market for Foreign Exchange Purchasing Power Parity The Effects of Currency Appreciation and Devaluations Bubbles Summary & Homework Problems III PRICING FOR GREATER PROFIT CHAPTER 12: MORE REALISTIC AND COMPLEX PRICING 135 New anecdote: Pricing Commonly Owned Products 135 Revenue Management 137 Advertising and Promotional Pricing 140 Psychological Pricing Summary & Homework Problems 141 CHAPTER 13: DIRECT PRICE DISCRIMINATION 145 New anecdote: Introduction 145 Why (Price) Discriminate? 147 Direct Price Discrimination 149 Robinson–Patman Act 150 Implementing Price Discrimination Schemes Only Schmucks Pay Retail 152 Summary & Homework Problems 153 CHAPTER 14: INDIRECT PRICE DISCRIMINATION 155 New anecdote: Indirect Price Discrimination 156 Volume Discounts as Discrimination 159 Bundled Pricing 160 Summary & Homework Problems 161 IV. STRATEGIC DECISION MAKING CHAPTER 15: STRATEGIC GAMES 167 New anecdote: Sequential-Move Games 168 Simultaneous-Move Games 170 What Can I Learn from Studying Games Like the Prisoners’ Dilemma? 177 Other Games 180 Summary & Homework Problems 184 Thursday, October 25, 2007 How movie studios play "chicken" Another gem from Mike Shor's collection, from the NY Times: The first principle of scheduling any film's release date is to avoid going directly against a similar movie. Studios realize that a standoff between films aimed at the same demographic -- kids, women, ''urban'' teenagers -- splits the vote, in effect, and hurts both films. ''No one is interested in going head to head in this business,'' Harper says. ''Someone is almost always going to give. It's just a question of who.'' Given the stakes involved, film companies generally disclose their future release dates well in advance, giving everyone time to minimize the chance of collision. But at the end of the year, with so many films vying for coveted berths, some jostling is inevitable. As Jeff Blake, vice chairman of Sony Pictures Entertainment, notes, ''There are only four weekends in December, so you're always going to be bumping into other movies.'' Posted by Luke Froeb at 9:23 PM 0 comments Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Google Buzz Labels: 15. Strategic games CHAPTER 16: BARGAINING 189 New anecdote: Strategic View of Bargaining Non-strategic View of Bargaining Summary & Homework Problems 196 V. UNCERTAINTY CHAPTER 17: MAKING DECISIONS WITH UNCERTAINTY 203 Opening anecdote: Random Variables & Sensitivity analysis Uncertainty in Pricing 207 Maximize Expected Profit or Minimize Expected Error Costs Run Natural Experiments to reduce uncertainty: Summary & Homework Problems 217 CHAPTER 18: AUCTIONS 189 (NOTE THIS IS A NEW CHAPTER BASED ON SPLITTING OLD UNCERTAINTY CHAPTER AND EXPANDING) New anecdote: Oral Auctions Sealed-Bid Auctions 212 Bid Rigging 213 Common-Value Auctions 215 Summary & Homework Problems 196 CHAPTER 19: THE PROBLEM OF ADVERSE SELECTION 221 New anecdote: Insurance and Risk 222 Anticipating Adverse Selection 223 Screening Signaling 227 Adverse Selection in Sales Adverse Selection in IPO’s 228 Summary & Homework Problems 229 CHAPTER 20: THE PROBLEM OF MORAL HAZARD 233 New anecdote: Insurance 233 Moral Hazard versus Adverse Selection 235 Shirking as Moral Hazard Moral Hazard in Lending 238 Summary & Homework Problems 240 VI. ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN CHAPTER 21: GETTING EMPLOYEES TO WORK IN THE FIRM’S BEST INTERESTS Opening anecdote: Incentive Conflict 248 Controlling Incentive Conflict 249 Marketing versus Sales 251 Franchising 252 A Framework for Diagnosing and Solving Problems 254 Summary & Homework Problems 256 CHAPTER 22: GETTING DIVISIONS TO WORK IN THE FIRM’S BEST INTERESTS Opening anecdote: Incentive Conflict between Divisions 262 Transfer Pricing 264 Functional Silos versus Process Teams 267 Budget Games: Paying People to Lie 269 Summary & Homework Problems 272 CHAPTER 23: MANAGING VERTICAL RELATIONSHIPS 277 New anecdote: Do Not Buy a Customer or Supplier Simply Because They Are Profitable 278 Evading Regulation 279 Eliminate the Double Markup 280 Aligning Retailer Incentives with the Goals of Manufacturers 282 Price Discrimination 284 Fighting a standards war Outsourcing 285 Summary & Homework Problems 286 VII. WRAPPING UP CHAPTER 24: YOU BE THE CONSULTANT 291 New anecdote: Excess Inventory of Prosthetic Heart Valves 291 High Transportation Costs at a Coal-Burning Utility 293 Overpaying for Acquired Hospitals 294 Large E&O Claims at an Insurance Company 296 What You Should Have Learned 298 EPILOG: CAN THOSE WHO TEACH, DO?