Section 1 Prokaryotes Chapter 23 Domain Bacteria

advertisement

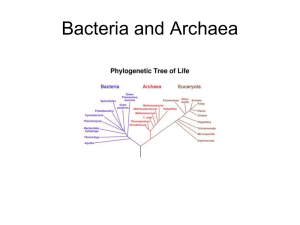

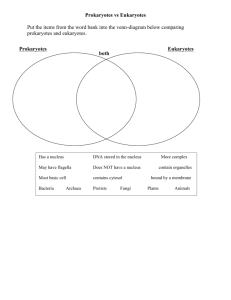

Chapter 23 Bacteria Table of Contents Section 1 Prokaryotes Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Objectives • Explain the phylogenetic relationships between the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. • Identify three habitats of archaea. • Describe the common methods used to identify bacteria. • Identify five groups of bacteria. • Explain the importance of nitrogen-fixing bacteria for many of Earth’s ecosystem. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Two Major Domains: Archaea and Bacteria • Prokaryotes are single-celled organisms that do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and can live in nearly every environment on Earth. • Although tiny, prokaryotes differ greatly in their genetic traits, their modes of nutrition, and their habitats. • Based on genetic differences, prokaryotes are grouped in two domains: Domain Archaea and Domain Bacteria. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Three Domains of Living Organisms Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Archaea • One of the ways in which archaea differ is the make up of their cell wall. Archaeal cells walls do not contain peptidoglycan. – Peptidoglycan is a protein-carbohydrate complex found in bacterial cell walls that make their cells walls rigid. • Archaea differ in the types of lipids in their cell membrane. Also, archaeal genes do not contain introns. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Archaea, continued • Archaeal Groups -3 groups – Archaeal groups include methanogens, halophiles, and thermoacidophiles. 1. Methanogens convert hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide into methane. They can be found in the intestines of organisms such as cattle and termites. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Archaea, continued 2. Halophiles are “salt-loving” archaea that live in very salty environments such as the Great Salt Lake and the Dead Sea. 3. Thermoacidophiles live in very hot, acidic environments, such as the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park. Some thermoacidophiles live at temperatures up to 110°C (230°F) and at a pH of less than 2. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Bacteria • Bacteria occur in many shapes and sizes. Most bacteria have one of three basic shapes: rod-shaped, sphere-shaped, or spiral-shaped. • Rod-shaped bacteria are called bacilli (singular, bacillus). An example of bacilli is Escherichia coli. • Sphere-shaped bacteria are called cocci (singular, coccus). An example of cocci is Micrococcus luteus. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Bacteria, continued • Spiral shaped bacteria are called spirilla (singular, spirillum). An example of spirilla bacteria includes Spirillum volutans. • Cocci that form chains similar to a string of beads are called streptococci. • Cocci that form clusters similar to a bunch of grapes are called staphylococci. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Three Bacterial Cell Shapes Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Characteristics of Bacteria Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Domain Bacteria, continued • Gram Stain – Most species of bacteria are classified into two categories based on the structure of their cell walls as determined by a technique called the Gram stain. – Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan in their cell wall, and they appear purple under a microscope after the Gram-staining procedure. – Gram-negative bacteria have a thin layer of peptidoglycan in their cell wall, and they appear reddishpink under a microscope after the Gram-staining procedure. Chapter 23 Gram Staining Section 1 Prokaryotes Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Gram Stain Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups • Bacteria are also classified by their biochemical properties and evolutionary relationships. 1. Proteobacteria – Proteobacteria are one of the largest and most diverse groups of bacteria, and contain several subgroups that are extremely diverse. – Members of this group include bacteria of the genus Rhizobium, the genus Agrobacterium, and the bacterium Escherichia coli. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups, continued 2. Gram-Positive Bacteria – Not all of the bacteria in this group are Gram-positive. Biologists place a few species of Gram-negative bacteria in this group because these species are genetically similar to Gram-positive bacteria. – Members of this group include the streptococcal species, Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus anthracis, and members of the genus Mycobacteria. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups, continued – Actinomycetes are Gram-positive bacteria, some species of which produce antibiotics. • Antibiotics are chemicals that inhibit the growth of or kill other microorganisms. Streptomycin and tetracycline are examples of antibiotics that are used medicinally. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups, continued 3. Cyanobacteria – Cyanobacteria use photosynthesis to get energy from sunlight, and make carbohydrates from water and carbon dioxide. During this process, they create oxygen as a waste product. – Once called blue-green algae, cyanobacteria are now known to be bacteria because they lack a membrane-bound nucleus and chloroplasts. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups, continued 4. Spirochetes – Spirochetes are Gram-negative, spiral-shaped bacteria that move by means of a corkscrew-like rotation. Some are aerobic. – Spirochetes can live freely or as pathogens. Pathogenic spirochetes include Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, and Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease. Chapter 23 Section 1 Prokaryotes Important Bacterial Groups, continued 5. Chlamydia – Gram-negative coccoid pathogens of the group Chlamydia live only inside animal cells. The cell walls of chlamydia do not have peptidoglycan. Chlamydia trachomatis causes the sexually transmitted infection called chlamydia. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Objectives • Describe the internal and external structure of prokaryotic cells. • Identify the need for endospores. • Compare four ways in which prokaryotes get energy and carbon. • Identify the different types of environments in which prokaryotes can live. • List three types of genetic recombination that prokaryotes use. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function • The major structures of a prokaryotic cell include a cell wall, a cell membrane, cytoplasm, ribosomes, and sometimes a capsule, pili, endospores, and flagella. 1. Cell Wall – Most prokaryotes have a cell wall. Bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan. Archaeal cell walls do not have peptidoglycan; instead, some contain pseudomurein, a compound made of unusual lipids and amino acids. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function, continued 2. and 3. Cell Membrane and Cytoplasm – Bacterial and archaeal cell membranes are lipid bilayers that have proteins. However, the lipids and proteins of archaeal cell walls differ from those of bacterial cell walls. – The cytoplasm is a semifluid solution that contains ribosomes, DNA, small organic and inorganic molecules, and ions. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function, continued 4. DNA – Prokaryotic DNA is a single closed loop of doublestranded DNA attached at one point to the cell membrane. – Along with a single main chromosome, some prokaryotes have plasmids, which are small, circular, self-replicating loops of double-stranded DNA. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function, continued 5. and 6. Capsules and Pili – Many bacteria have an outer covering of polysaccharides called a capsule that protects the cell against drying, pathogens, or harsh chemicals. – Pili are short, hairlike protein structures on the surface of some bacteria that help bacteria connect to each other and to surfaces, such as those of a host cell. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Bacterial Capsule Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Pilus Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function, continued 7. Endospores – Some Gram-positive bacteria can form a thickcoated, resistant structure called an endospore when environmental conditions become harsh. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structure and Function, continued Prokaryotic Movement – Many prokaryotes have long flagella that allow the prokaryotes to move toward food sources or away from danger. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Structural Characteristics of a Bacterial Cell Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Parts of a Prokaryotic Cell Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Nutrition and Metabolism • Prokaryotes obtain nutrients either from the nonliving environment or by utilizing the products or bodies of living organisms. – Heterotrophs obtain carbon from other organisms. – Autotrophs obtain their carbon from CO2. – Chemotrophs get energy from chemicals in the environment. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Prokaryotic Habitats • Different prokaryotic species live in different environments. • Temperature requirements range from 0°C to 110°C. • Most prokaryotic species grow best at a neutral pH. Chapter 23 Section 2 Biology of Prokaryotes Reproduction and Recombination • Genetic recombination in bacteria can occur by the following three ways: 1. transformation (taking in DNA from the outside environment) 2. conjugation (exchanging DNA with other bacteria via pili) 3. transduction (transmission of bacterial DNA via viruses). Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Objectives • Describe the ways in which bacteria can cause disease in humans. • Explain how a bacterial population can develop resistance to antibiotics. • Identify reasons for recent increases in the numbers of certain bacterial infectious diseases. • Identify ways of preventing a foodborne illness at home. • List four industrial uses of bacteria. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria and Health • Human diseases may result from endotoxins or exotoxins produced by bacteria or from the destruction of body tissues. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria and Health, continued • Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance – A mutation in the DNA of a single bacterium can confer resistance to an antibiotic. – Cells with the mutant gene have a selective advantage when the antibiotic is present. – Mutant cells take over the population when the normal cells die. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria and Health, continued • Emerging Infectious Diseases Caused by Bacteria – The number of certain bacterial diseases has increased because of the increase in the number of antibiotic resistant bacteria, the movement of people into previously untouched areas, and global travel. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria and Health, continued • Food Hygiene and Bacteria – Foodborne illnesses can be avoided by selecting, storing, cooking, and handling food properly. – Frequent hand washing in hot, soapy water is also very important. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Important Bacterial Diseases Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria in Industry • Many species of bacteria are used to produce and process different foods, to produce industrial chemicals, to mine for minerals, to produce insecticides, and to clean up chemical and oil spills. • Biologists have learned to harness bacteria to recycle compounds in a process called bioremediation, which uses bacteria to break down pollutants. Chapter 23 Section 3 Bacteria and Humans Bacteria and Food Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept