Case 1 35 yo roofer falls of a 12 ft roof at work. He is wearing a

advertisement

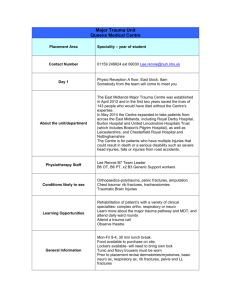

Case 1 35 yo roofer falls of a 12 ft roof at work. He is wearing a helmet, but does land on his head and left side. There is a 2 minute LOC, and he is confused and disoriented, GCS 13 (E3V4M6). No past medical history He becomes hypotensive as he rolls into the trauma bay: 90 palp, HR 86, SaO2 100%2L, RR 18. His chest is non-tender with air entry bilaterally, abdomen firm with mild tenderness in the LUQ, and there are no apparent orthopaedics injuries. FAST is positive. CXR and pelvic Xrays are normal, no rib #‘s. ABG – hbg 125. How would you like to proceed? He is persistently hypotensive 90/45, but responds to his first 2L NS, BP 100/50. You call for blood, and begin transfusion. He gets a panscan: CT head, chest, and spine are normal. what do you see here? (CT abdo) – grade 3 splenic laceration which is actively bleeding. How do you manage this? The patient goes to interventional radiology for embolization. Post procedure his vitals stabilize and he avoids a laparotomy. He goes up to Unit 71. Case 2 50 yo M obese dump truck driver. He flipped his dump truck while driving at highway speeds North of Calgary, no other vehicles involved. There is a prolonged extrication – it takes 2 hours to get him out, and for this duration he is pinned underneath the truck. He is intubated at the scence for low GCS, hypotensive with minimal blood loss at the scene. EMS questions the smell of EtOH. In the trauma bay his vitals are: 78/40 post 2L NS, HR 120, SaO2 96% 100%FiO2, temp 36.4. Good end tidal CO2. There is a large boggy hematoma to the back of scalp, slowly bleeding from same, which is stapled shut. There is equal air entry bilaterally. His abdomen is soft, pelvis is stable. VBG – hbg 90, Ph 7.26, lactate 3.5. What are the places you can lose blood in a trauma? Chest, abdomen, pelvis, femurs, on the street (scalp lac) FAST is indeterminate. The rest of ED ultrasound – no tamponade or pneumothoracies. CXR show pulmonary contusions and 2 rib fractures but no pneumothorax or effusion, no unstable pelvis on plain film pelvis. Massive transfusion protocall initiated. First set of coags, plts 80, elevated INR/PTT. What is the significance of this bloodwork? DIC 1|Page You have assessed thorax, abdomen, femurs, scalp wound stapled. No obvious source of bleeding, so you come back to the abdomen, and repeat FAS is negative this time. Where do you think the bleeding is coming from? Would you use DPL in this situation? Trauma surgeon decides to do DPL in trauma bay – negative DPA, DPL grossly negative (can read a paper through it, didn’t wait for the RBC count). He is still unstable, but taken to the CT scanner because there isno obvious source of bleeding and he is deteriorating. The CT scan shows a massive hematoma, with active exsanguination from bleeding arteries in his posterior torso. The PTT continue to increase, plts are now 60. Worsening DIC. He is taken to interventional to try and stop the bleeding. He arrests and dies on the table. Case 3 4 yo F jumped out of a 2 storey window with her little brother. CPS was called by neighbours because they heard the children crying, both brought to ACH by EMS, code 77. Neither the patient nor her parents speak English, they are from Vietnam. No vital sign abnormalities. Left leg is deformed at femur, no other obvious abnormalities. This is confirmed by Xray whcich shows a displaced and angulated midshaft femur fracture with an intact pelvis. She is slightly drowsy – was given a bit too much morphine by EMS (4mg IV). Chest and abdomen are non-tender. What do you think about the mechanism? Significant deceleration from speed, risk for hollow viscus and renal injuries. No FAST available. She is given a femoral nerve block which allows us to straighten the leg, reduced it significantly. She is more comfortable, but now has very mild abdominal tenderness. She becomes more responsive, GCS 15, acting appropriate, and we decide not to CT her head. Labs come back normal, no elevated lipase, LFT’s. In and out urine shows +++RBC on dip. What is your approach to hematuria in BAT in an adult? In this patient, hematuria in pediatric BAT? Hematuria in BAT Of all injuries to the genitourinary system in blunt trauma, the kidneys are most commonly involved. The gross majority of injuries are stage 1 (renal contusion), which require no further management, and stage 2-5, which require additional testing and follow up by urology, make up 5% of blunt renal trauma. It therefore makes sense that the goal should be to identify patients with a greater likelihood of significant renal trauma without subjecting the remainder to unnecessary and potentially harmful diagnostic procedures. Hematuria is the best indicator of traumatic injury to the urinary tract. It must be obtained from a first catheter or void specimen, as subsequent samples are diluted during resuscitation. A positive urine dipstick has been shown to have a specificity and sensitivity of 97 %. Microscopic hematuria is defined as a positive dipstick or >5RBC’s /HPF. Gross hematuria is visible blood of any degree. 2|Page The degree of hematuria and severity of renal injury do not consistently correlate. How do we know should undergo imaging for renal injury? The largest series looking at renal trauma and hematuria has been ongoing for 25 years and has had 3 updates since the start (J urol 1995;154:352). They have found that patients with blunt abdominal trauma and hematuria should be imaged only if: Gross hematuria Microscopic hematuria in the presence of shock (SBP <90) Significant deceleration injury Other intra-abdominal injuries that require imaging. Microscopic hematuria in the absence of shock can be monitored clinically, and do not need urgent imaging. With this protocall (n=1588 BAT), they have not missed any significant renal injury requiring intervention, nor renal vascular injuries which have been found to occur in the absence of hematuria. The imaging of choice is a CT scan with IV contrast. (Note: in the low risk group, the CT scans that were ordered were performed for concern of other intra-abdominal injury or at the discretion of the emergency physician). Pediatrics: are they just little adults? There is less consensus when to image for renal injury. A large retrospective study to validate the adult prediction rules in pediatrics found that no clinically significant injuries would be missed applying the criteria above (J Urol 2004;171:822). They also re-analysed the data from previous studies on the subject and found that at most 2 significant injuries would have been missed out of a pooled 382 patients. A caveat to the adult rule is that hypotension is not a good marker of shock in children, and that serial haemoglobin is best followed instead. BACK TO CASE: CT abdo/pelvis normal. Child was admitted to ortho for femur fracture. Case 4 22 yo M, run over by combine wheel near High River. There is no LOC, GCS 15 throughout, transported by STARS to FMC. He is semi-lateral, propped up with blankets, his pelvis looks grossly distorted with a shortened right leg. Initial VS: HR 123; BP 99/50; RR 20; SaO2 99 5L; temp 37 Has 2 x 18” AC. Patent airway, a little confused (GCS 14), chest clear, abdomen soft, rectal high riding prostate. FAST is negative for 2 operators. What do you think of this pelvic XR? 7-9 mm symphysis diastasis, bilat pubic root #, bilat inf rami #, bilat zone 1 sacral #, L4/L5 TP # What do you think about the negative FAST in the Pelvic Fracture? 3|Page FAST in pelvic fractures: 9% of BAT patients have pelvic fractures, and the mortality rate approaches 50% in hemodynamically unstable patients. The sources of life-threatening bleeding are two-fold, from intra-peritoneal and retroperitoneal structures. Bleeding from the abdomen requires laparotomy, while bleeding from the retroperitoneum mandates angiography and embolization. Decisions about where to send patients from the emergency department are difficult, and must be made emergently in these patients. The sensitivity of FAST in pelvic fractures is overall decreased to detect free intraperitoneal fluid. The SN is approximately 81% and SP 87% (J trauma 2006;61:97) to detect any free fluid in the context of pelvic fractures. It does also not differentiate between hemoperitoneum and uroperitonemum. FAST is the first screening tool used in the approach to the unstable patient with a pelvic injury, and is utilised to triage the patient to the OR or to angio/pelvic fixation. The low SN/SP is thought to be attributable to distorted retroperitoneum from fracture and hematoma, as well as leakage of retroperitoneum and urine which confuse results. BACK TO CASE: BP now 90/45, HR 130, more confused. You are getting bertha ready, and have 2L NS running. The pt is hemodynamically unstable with a pelvic fracture and a negative FAST. You are concerned for intraperitoneal hemorrhage, and want to triage this patient to either angiography or to the OR. What is your decision here? This is a very difficult scenario, and there is no right decision. Decisions are collaborative and made with ortho, trauma and the emerg teams. This patient goes to angiography and had his right internal iliac artery embolized with coil. He is persistently hypotense and tachycardic, bertha running 1:1:1. Coags at this point are normal. From angio he goes directly to the OR for a combined ortho / gen surg case. Ortho places an ASIS ex fix, and trauma surgery repair the ruptured bladder, rectal tear, and leave the large retroperitoneal hematoma alone. Case 5 17 yo M motorbike accident. A group of friends on motorbikes were driving ~120kph on a paved back road near Airdrie. None were wearing leathers, all have helmets, and one boy accidentally cut off his friend. The patient flipped numerous times with his bike, and came to a stop with his bike. Despite damage to his helmet, there was no LOC, no amnesia, his vitals were stable with EMS. On arrival in the trauma bay, his first set of vitals are: HR110; BP 135/80; RR 20; Sa02 99 RA; temp 37.3. Any concerns? He is tachycardic but hypertensive. Continue with primary survey 4|Page He is talking full sentences, GCS 15, alert and oriented. He has pain all over from his significant road rash. Air entry is equal bilaterally. The abdomen is difficult to assess because he has road rash over his abdomen and it is very painful to touch. The rest of the primary and secondary surveys are unremarkable, no other obvious injuries. FAST negative, blood work normal, C/S films normal. He is slated to go to the OR with Plastics to debride his significant road rash. His abdomen is still very tender and slightly firm. What would you like to do, and what are your immediate concerns? The concern here is that the patient will be in the OR with a potential intra-abdominal injury. You decide to CT his abdomen. The radiologist calls you and says, there is free fluid in 3 slices, but no intra-abdominal injury identified. Can you comment on the significance of isolated free fluid on CT? Free Fluid Dilemma: In the context of a solid organ injury, free fluid is attributable to bleeding from the injury site. However, if the only finding on CT is free fluid with no other injury, this may signify one of 3 things: undetected solid organ injury, bowel injury, or mesentery injury that may not necessarily require a laparotomy. This is important because the mortality rate of missed hollow viscus injuries is as high as 31%, more so if not diagnosed within 24 hours. This presents the dilemma of what to do in a stable patient with free fluid on CT with no identified intra-abdominal injuries? A systematic review on the subject (J trauma 2002;53:79) found an incidence of this problem to be 2.8% of CT scans in BAT, with a range of 0.6-4% in the individual studies. The overall therapeutic laparotomy rate was 27% of all performed, which is not high enough to mandate therapeutic laparotomies. If this was the case 73% would be non-therapeutic; conversely, if no lapatoromies were performed then 27% would have missed diagnoses. Seatbelt sign and larger amount of free fluid (greater number of slices with fluid) are more predictive of a positive laparotomy. The review concludes that stable patients with free fluid in the absence of other findings don’t require laparotomy, but should be observed, with serial exams. If altered mental status i.e. head injury or intubated, they recommended DPL. It is unclear what the exact next step should be, but there is enough evidence to suggest that an urgent laparotomy is not required. A pediatric prospective observational study n=537 () found that 8% had isolated free intraperitoneal fluid. Of these children, 17% (7) were identified during hospitalisation to have intra-abdominal injuries. Patients with small amount of free fluid, no abdominal tenderness, and normal level of consciousness were at lowest risk for subsequent injury. The authors concluded these children can be considered for discharge. BACK TO CASE: He is admitted to trauma for observation, and goes to the OR that night after an uneventful afternoon with no worsening of his abdominal pain, changes in his haemoglobin, or vital sign abnormalities. Case 6 5|Page 32 yo F assaulted with a baseball bat by her boyfriend. She has been drinking, and appears intoxicated. She doesn’t know if she lost consciousness, or really where she was struck with the bat. Her vitals are HR110; BP100/50; RR26; SaO2 96%RA, temp 37.4 There is a large hematoma around her right eye, which is swollen shut, and has tenderness “all over her body”, but more so in her C spine, face, and abdomen (she remembers “he got a couple of good blows in here”, pointing to her LUQ). The FAST positive, persistently tender LUQ on re-examination. How would you like to proceed? The bloodwork is unremarkable, and CT scan head, facial bones and cervical spine show nil acute. CT abdomen is normal. You wait a few hours, reassess her after she has sobered up a bit, and she is still persistently tender in the LUQ. What would you like to do with this negative CT in the context of persistent tenderness? The Negative CT scan: The debate over the negative CT scan is ongoing, and is important because there is sometimes a misconception that a CT scan can “rule out everything”. The main fear of foregoing an admission for observation is that significant injuries will be missed, such as duodenal or hollow viscus perforation. There are numerous studies with very low false negative rates on CT, but do not comment on how this relates to management. A prospective, multi-institutional study from the trauma services perspective concluded that adult trauma patients with normal abdominal CT scans can safely be discharged from the emergency department (J trauma 1998;44:273). The 4 study sites enrolled consecutive patients over a 2 year period, and concluded that a negative CT on a preliminary interpretation (radiology resident, trauma surgeon) had a negative predictive value of 99.63%. There were 4 missed injuries out of 2082, 2 jejunal perforations and a retroperitoneal hematoma, diagnosed while still in hospital. A sigmoid colon perf was diagnosed when the patient returned with abdominal pain after discharge. 97% of these patients had other extra-abdominal injuries, which may or may not on their own prompted admission (it does not include this detail in the study). A recent pediatric study (Academic Emerg Med 2010;15:89) examined the same in the pediatric population. They found a NPV of 100%. Of their study population (n=1085) 32% were discharged home and 68% were admitted for observation or management of other extra-abdominal injuries. None of the patients discharged home and 2 of the admitted patients had an identified intra abdominal injury (1 non-operative perinephric hematoma, 1 bowel contusion with a non-therapeutic laparotomy in an 11 y F with a seatbelt sign) Can we conclude that every patient with a normal CT scan can be discharged from hospital? No, but these studies support our decisions when we do decide to discharge patients from the emergency department. The decision to discharge must be based on a number of factors, including concurrent injuries, any impairment in judgement (i.e. intoxication, minor head injury), mechanism of injury, and how concerned we are of an underlying intra-abdominal injury. BACK TO CASE: She was observed until the end of shift, she was sober, and her abdominal pain had dissipated. You look through REDIS and see she has had numerous visits for minor head injuries and fractures. She was referred to the woman’s shelter and decided to finally press charges against her boyfriend 6|Page