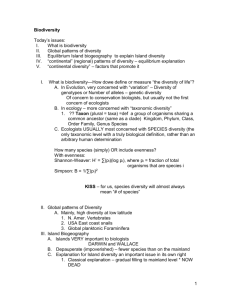

Island Biogeography: Equilibrium Model & Species Diversity

advertisement

Island Biogeography Notes Islands are interesting from a biogeography standpoint because anything that lives on an island had to get there from somewhere else, or evolve from something that came from somewhere else. Everything living on islands has relatives in other places. We can also think about islands in a broader context than just oceanic islands. Mountain peaks can be islands in a sense; they offer a specific alpine habitat at the top but are surrounded by lower elevation land. Species that are adapted to life at the top might not be able to survive in the surrounding lowlands. When this happens, the mountain peaks are called "sky islands." Earth is an island and all other planets are islands, whether or not they have beaches and palm trees. Two scientists, Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson, developed a theory to describe island biodiversity. Their theory is called the island equilibrium model. The island equilibrium model describes the number of species on an island based on the immigration and extinction rates of species on that island. Species have to get to the island from somewhere else, which is the immigration part, and species go extinct from the island as they run out of resources. To understand their theory, take a look at the graph to the left. The axis on the bottom of the graph is the number of species. If we follow the blue line, it shows that as the number of species increases, the rate of immigration begins to decrease. That's because as more and more species arrive, the chances grow that that species is already present. Consider this…if you went to Mars with your dog and cat, Mars would go from a population of zero species to a population of three species. If your cousin came next, maybe she'd bring her cat and a goldfish. So now, when you include the goldfish, Mars has four different species on it. Going from zero to three species is a much bigger leap than going from three to four is. Another factor to consider as a new place is colonized is that the rate of extinction increases. That's because (1) there's just more things to go extinct and (2) there's more competition. You can see this illustrated in the orange line of the graph. In MacArthur and Wilson's model, two things affect immigration and extinction rates. The first is how close the island is to the mainland (or Earth, if we are talking about Mars). The "mainland" is just the source of new immigrants to the island. Assuming all new species have to immigrate to the island from the mainland, closer islands will have more species on them than far islands, just because closer islands are easier to reach. Extinction is lower on islands close to the mainland because of the likelihood of immigration. There is more of a chance that new immigrants will arrive and keep a species in existence on that island. The graph to the left shows how an island closer to the mainland would have higher immigration rates, and therefore maintain a higher number of species. The taller the blue line is, the farther to the right the two lines cross. The second thing that affects immigration and extinction rates is the size of the island. For immigration, think of the island as a target, for birds flying above or geckoes riding seagrass rafts on the water (it happens, really!). A bigger target is easier to hit than a small one, and a big island is more likely to have species land on it by chance than a small one is. Larger islands have more space than smaller islands, so there are likely to be more resources available for species to use. The opposite is true for smaller islands. Therefore extinction rates are larger on small islands. This can be seen in the graph to the left. If we graph the rates of immigration and extinction, we can see the number of species on an island varies: The equilibrium part of the island equilibrium model refers to the number of species. The island will reach equilibrium when extinction rates equal immigration rates. That is the A, B, C, and D in the graph above, which are different depending on size and distance. The island equilibrium model is a great way to think about the things that influence species diversity on islands. However, it does not take into account everything that can happen. Disturbances such as hurricanes affect life on islands, and the model does not take into account evolution or interactions between species, such as competition. Extinction from islands does not mean the species goes extinct globally. Extinction here just means there are no individuals of that species left on the island in question. If only one individual of a species arrived on an island, then the species will be extinct from the island after that individual dies—unless, of course, more individuals of the same species immigrate to the island. Review Questions 1. According to the island equilibrium model, if you look at two islands of the same size, but one is 10 miles away from the mainland and one is 50 miles away from the mainland, which island will have higher immigration rates? The closer island will have more immigrants arriving because of "spillover" from the mainland. 2. If you consider two islands that are both 50 miles away, but one is 10 square miles in size and the other is 100 square miles, which will have higher extinction rates? Under the island equilibrium model, the smaller island will have higher extinction rates. The bigger island will have more resources and more ecological roles to fill. 3. What are three things that influence species diversity that the island equilibrium model does not take into account? The island equilibrium model does not take into account disturbance, evolution, or competition. 4. Why do big islands have higher immigration rates than small islands? Bigger islands are like bigger targets for immigrants. Birds flying above are more likely to see a big island than a small one, and more things wash up by chance on a bigger island than a smaller one. 5. Knowing what you do about island biogeography, which type of island would maximize the number of species on it? A large island close to the mainland would have the most species. A small island far from the mainland would have the least.