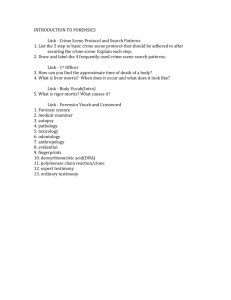

Basic Stages in a Search

advertisement

Crime Scene Analysis Chapter 3 Steps as they are outlined in the powerpoint: • • • • • Securing and isolating the scene; • Recording the scene; • Searching and collecting evidence; • Packaging, transporting and storing evidence. 10 Basic Stages in a Search http://harfordmedlegal.typepad.com/forensics_talk/crime-scene-procedures.html • • • • • • • • • • • • 1a. Approach scene b. Secure and protect scene 2a. Initiate preliminary survey b. Determine scene boundaries 3. Evaluate physical evidence possibilities 4. Prepare narrative description 5. Depict scene photographically 6. Prepare diagram/sketch of scene 7. Conduct detailed search 8. Record and collect physical evidence 9. Conduct final survey 10. Release crime scene Approach Scene • Be alert for discarded evidence • Make pertinent notes as to possible approach/escape routes First Responders vs. Law Enforcement Secure and Protect Scene • Take control of scene on arrival • Determine extent to which scene has thus far been protected • Ensure adequate scene security • Obtain information from personnel who have entered scene and have knowledge relative to its original conditions—document who has been at scene** first responders** • Take extensive notes—do NOT rely on memory!! • Keep out unauthorized personnel and begin recording who enters and leaves Preliminary Survey and Determine Scene Boundaries The survey is an organizational stage to plan for the entire search. – A cautious walk-through of the scene – Person-in-charge maintains definite administrative and emotional control – Select appropriate narrative description technique – Acquire preliminary photographs – Make known the extent of the search area—usually expand initial perimeter – Organize methods and procedures needed to recognize special problem areas – Identify and protect transient physical evidence – Develop a general theory of the crime continued • Make extensive notes to document scene – Physical and environmental conditions – Assignments – Movement of personnel, etc. • On vehicles: – Get VIN number – License plate number – Position of key – Odometer reading – Gear shift position – Amount of fuel in tank – Lights “on” or “off”???? Evaluate Physical Evidence Possibilities • Based upon what is known from the preliminary survey, determine what evidence is likely to be present. – Concentrate on the most transient evidence and work to the least transient forms of this material. (outdoor crime scene with forecast of rain) – Focus first on evidence in plain sight/open view with easy access. Then move on to evidence in out of view locations or those PURPOSELY hidden. • Consider whether the evidence appears to have been moved inadvertently. WAS SOMETHING MOVED ON PURPOSE? – Evaluate whether or not the scene and evidence appears intentionally "contrived". WAS IT A SET UP?! Prepare Narrative Description • The purpose of this step is to provide a running narrative of the conditions at the crime scene. – Consider what should be present at a scene (victim's purse or vehicle) and is not observed – Consider what is out of place (ski mask). • Represent scene in a "general to specific" scheme. Consider situational factors: lights on/off, heat on/off, newspaper on driveway/in house, drapes pulled, open or shut. • Do not collect evidence at this point and keep the narrative description organized. • Methods of narrative: written, audio, video. Photograph Scene • Begin photography as soon as possible - plan before photographing. • Document the photographic effort with a photographic log. • Insure that a progression of overall, medium and close-up views of the scene is established. • Use recognized scale device for size determination when applicable. – When a scale device is used, first take a photograph without the inclusion of this device. • Photograph evidence in place before its collection and packaging. • Be observant of and photograph areas adjacent to the crime scene - points of entry, exits, windows, attics, etc. • Consider feasibility of aerial photography. Photography continued…. • Photograph items, places, etc., to corroborate the statements of witnesses, victims, suspects. • Take photographs from eye-level, when feasible, to represent scene as it would be observed by normal view. • Film is relatively cheap compared to the rewards obtained do not hesitate to photograph something which has no apparent significance at that time - it may later prove to be a key element in the investigation. • Prior to lifting latent fingerprints, photographs should be taken 1:1, or use appropriate scale. Photography continued….. • Number designations on sketch can be coordinated with same number designations on evidence log in many instances. • General progression of sketches: – – – – – Lay out basic perimeter Set forth fixed objects, furniture, etc. Record position of evidence Record appropriate measurements- double check Set forth key/legend, compass orientation, etc. Photography Unit Prepare diagram/sketch of scene • The diagram establishes permanent record of items, conditions, and distance/size relationships - diagrams supplement photographs • Rough sketch is drawn at scene (normally not drawn to scale) and is used as a model for finished sketch. • Typical material on rough sketch: – – – – – – – – – – – – Specific location Date Time Case identifier Preparer Weather conditions Lighting conditions Scale or scale disclaimer Compass orientation Evidence Measurements Key or legend Conduct Detailed Search • Accomplish search based on previous evaluation of evidence possibilities. • Conduct search in a general manner and work to the specifics regarding evidence items. • Use of specialized search patterns (e.g., grid, strip/lane, spiral) are recommended when possible. Four basic premises: 1. The best search options are typically the most difficult and time consuming. 2. You cannot "over-document" the physical evidence. 3. There is only one chance to perform the job properly. 4. There are two basic search approaches, in this order: (1) A "cautious" search of visible areas, taking steps to avoid evidence loss or contamination. (2) After the "cautious" search, a vigorous search for hidden/concealed areas. TYPES OF SEARCH PATTERNS • • • • • GRID INWARD SPIRAL OUTWARD SPIRAL PARALLEL ZONE Record and Collect Physical Evidence • Photograph all items before collection and enter notations in photographic log (remember- use scale when necessary). • Complete evidence log with appropriate notations for each item of evidence. • Ensure that evidence or the container of evidence is initialed by investigator collecting the evidence. • Do not handle evidence excessively after recovery. • Seal all evidence containers at the crime scene. • Do not guess on packaging requirements different types of evidence can necessitate different containers. • Be sure to obtain appropriate "Known" standards (e.g., fiber sample from carpet). • Constantly check paperwork, packaging notations, and other pertinent recordings of information for possible errors which may cause confusion or problems at a later time. The Search • The search for physical evidence at a crime scene must be thorough and systematic. • The search pattern selected will normally depend on the size and locale of the scene and the number of collectors participating in the search. • For a factual, unbiased reconstruction of the crime, the investigator—relying upon his or her training and experience—must not overlook any pertinent evidence. • Physical evidence can be anything from massive objects to microscopic traces. 26 Beyond The Crime Scene • The search for physical evidence must extend beyond the crime scene to the autopsy room of a deceased victim. • Here, the medical examiner or coroner will carefully examine the victim to establish a cause and manner of death. • As a matter of routine, tissues and organs will be retained for pathological and toxicological examination. • At the same time, arrangements must be made between the examiner and investigator to secure a variety of items that may be obtainable from the body for laboratory examination. 27 The Search • Often, many items of evidence are clearly visible but others may be detected only through examination at the crime laboratory. • For this reason, it is important to collect possible carriers of trace evidence, such as clothing, vacuum sweepings, and fingernail scrapings, in addition to more discernible items. 28 Beyond The Crime Scene • The following are to be collected and sent to the forensic laboratory: 1. Victim’s clothing 2. Fingernail scrapings 3. Head and pubic hairs 4. Blood (for DNA typing purposes) 5. Vaginal, anal, and oral swabs (in sex related crimes) 6. Recovered bullets from the body 7. Hand swabs from shooting victims (for gunshot residue analysis) 29 Packaging • Each different item or similar items collected at different locations must be placed in separate containers. Packaging evidence separately prevents damage through contact and prevents cross-contamination. • The well-prepared evidence collector will arrive at a crime scene with a large assortment of packaging materials and tools ready to encounter any type of situation. 30 Packaging • Forceps and similar tools may have to be used to pick up small items. • Unbreakable plastic pill bottles with pressure lids are excellent containers for hairs, glass, fibers, and various other kinds of small or trace evidence. • Alternatively, manila envelopes, screw-cap glass vials, or cardboard pillboxes are adequate containers for most trace evidence encountered at crime sites. • Ordinary mailing envelopes should not be used as evidence containers because powders and fine particles will leak out of their corners. 31 Packaging • Small amounts of trace evidence can also be conveniently packaged in a carefully folded paper, using what is known as a “druggist fold.” • Although pill bottles, vials, pillboxes, or manila envelopes are good universal containers for most trace evidence, two frequent finds at crime scenes warrant special attention. – If bloodstained materials are stored in airtight containers, the accumulation of moisture may encourage the growth of mold, which can destroy the evidential value of blood. – In these instances, wrapping paper, manila envelopes, or paper bags are recommended packaging materials. 32 Chain of Custody • Chain of Custody—A list of all persons who came into possession of an item of evidence. • Continuity of possession, or the chain of custody, must be established whenever evidence is presented in court as an exhibit. • Adherence to standard procedures in recording the location of evidence, marking it for identification, and properly completing evidence submission forms for laboratory analysis is critical to chain of custody. • This means that every person who handled or examined the evidence and where it is at all times must be accounted for. 33 Obtaining Reference Samples • Standard/Reference Sample—Physical evidence whose origin is known, such as blood or hair from a suspect, that can be compared to crime-scene evidence. • The examination of evidence, whether it is soil, blood, glass, hair, fibers, and so on, often requires comparison with a known standard/reference sample. • Although most investigators have little difficulty recognizing and collecting relevant crime-scene evidence, few seem aware of the like necessity and importance of providing the crime lab with a thorough sampling of standard/reference materials. 34 Crime Scene Safety • The increasing spread of AIDS and hepatitis B has sensitized the law enforcement community to the potential health hazards that can exist at crime scenes. • In reality, law enforcement officers have an extremely small chance of contracting AIDS or hepatitis at the crime scene. • The International Association for Identification Safety Committee has proposed guidelines to protect investigators at crime scenes containing potentially infectious materials that should be adhered to at all times. 35 Conduct Final Survey • This survey is a critical review of all aspects of the search. • Discuss the search jointly with all personnel for completeness. • Double check documentation to detect inadvertent errors. • Check to ensure all evidence is accounted for before departing scene. • Ensure all equipment used in the search is gathered. • Make sure possible hiding places of difficult access areas have not been overlooked in detailed search. • Critical issues: have you gone far enough in the search for evidence, documented all essential things, and made no assumptions which may prove to be incorrect in the future? Release Crime Scene • Release is accomplished only after completion of the final survey. • At minimum, documentation should be made of : – Time and date of release – To whom released – By whom released • Ensure that appropriate inventory has been provided as necessary, considering legal requirements, to person to whom scene is released . • Once the scene has been formally released, reentry may require a warrant. • Only the person-in-charge should have the authority to release the scene. This precept should be known and adhered to by all personnel. • Consider the need to have certain specialists serve the scene before it is released (e.g., blood pattern analysts, medical examiner). Evidence Collection The Fourth Amendment • Do you know what it states? • “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but up on probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” • 2 types of searches • Those that require a warrant • Warrantless search Is this legal? • A private security officer searches the backpack without a warrant and found something illegal, could they call the police and turn the evidence over to the authorities? • LEGAL • The 4th currently only applies to searches by government officials (e.g., police officers, court officials, etc.) and not to private security guards who, btw, currently vastly outnumber police officers • a police officer probes (touches and feels) the outside of a opaque bag that is in public view without a warrant… Legal? • NOT LEGAL Is this Legal? • (April, 1991)An officer assumes you are Jeffrey Dahmer and arrests you. After placing you under arrest, searches your person and finds your pocket full of cocaine… is this search legal? • LEGAL • In the course of an arrest, police officers have the right to search your person and the immediate area to seize evidence (including items found after a person has been incorrectly arrested) and to declare you not a threat. Mincey v. Arizona • We're in Tucson, Arizona, and undercover police officer Barry Headricks had previously purchased heroin from Rufus Mincey in the Mincey’s apartment. On this particular, fateful day, Headricks made arrangements with Mincey in the apartment to go get some money and return to buy heroin. Officer Headricks left and returned with nine other plainclothes officers and a deputy county attorney, but without money or a warrant. • Present in the apartment with Mincey were his girlfriend and three associates, one of whom admitted the original officer, but then realized it was a raid and briefly closed the door on the group behind Headricks. • Headricks headed immediately to a bedroom where he knew the heroin was concealed and the other officers forcibly entered the apartment in time to hear a volley of shots from the bedroom and finally to see Headricks emerge from said bedroom and collapse on the front room floor, fatally wounded. • The narcotics officers found Mincey and his girlfriend wounded in the bedroom as well as, one of the associates caught a wild round inside bedroom that came through the wall, from the front room, into his head. • Within ten minutes Tucson homicide investigators arrived at the apartment to relieve the narcotics officers, who then departed. They supervised the removal of the officer, who died a few hours later in the hospital, the suspects, and secured the scene. • Due to the emergency-exigent circumstance the officers started searching. For four days. They searched. They photographed. They diagramed. They opened drawers, closets and cupboards. They emptied clothing pockets, dug bullet fragments from out of the walls and floors, cut out sections of the carpeting and seized, in all, between 200 and 300 evidentiary items. • Obviously, much of the evidence introduced against Mincey at trial came from the four-day search, i.e., photos, diagrams, slugs, shell casings, handguns, narcotics, paraphernalia, etc. • The defense, of course, argued there should have been a search warrant. The prosecution and the Arizona Supreme Court said the search of a homicide scene should be an exception to the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement. • What do you think?? Mincey v. Arizona • drug bust went wrong, resulting in the death of an undercover police officer and the wounding of several others • detectives who then spent 4 days seizing 200-300 pieces of evidence • led to the conviction of Mincy on homicide and narcotics charges • But was this legal? • Did you say Emergency-exigent circumstances? • Supreme Court later ruled: a warrantless search based on an emergency is limited in duration Michigan v. Tyler (1978) • A fire breaks out in defendant's furniture store shortly before midnight and the fire department responds and is "just watering down smoldering embers" when the fire chief arrives at 2:00 a.m. He is informed by his assistant that two plastic containers of flammable liquid had been found in the building. • The two then use portable lights and entered the gutted store, which was still filled with smoke and steam, to examine the containers. (No warrant or consent.) • The chief concludes there is an arson possibility and he calls a police detective who arrives about 3:30 a.m. The detective takes some photos and he and the chief look around briefly. The steam and smoke make it impossible, however, and they and the fire fighters leave at 4:00 a.m. • At 8:00 a.m. the chief and his assistant return and look around briefly. The assistant and the detective return at 9:00 a.m. They find evidence not previously visible, due to the smoke and steam, burned carpet and tape, and remove those items in a brief search. • On three subsequent occasions, four days after the fire, seven days after the fire, and twenty-five days after the fire, other investigators, without warrant or consent, return to the scene, search and remove arson evidence. • The defense objects to the admission of all the evidence, but the defendants are convicted. The Michigan Court of Appeals agrees to hear a case from the defendants. • The Michigan Supreme Court reverses the conviction and orders a new trial, holding that all entries after the fire was extinguished at 4:00 a.m. were unconstitutional, without warrant or consent. • The Supreme Court affirms the Michigan Supreme Court's decision as to all re-entries after the 9:00 a.m. search, those four days, seven days, and twenty- five days after the fire, but permits the use of the evidence found during the fighting of the fire and through the 9:00 a.m. search. Michigan v. Tyler • A fire broke out in a furniture store before midnight and was extinguished by the fire department. At 2 AM, the investigation by fire and police officials that began, was halted at 4 AM due to darkness, heat and steam. During the following three weeks, investigators returned to the scene repeatedly to collect and remove evidence for a possible arson investigation. • Tyler was ultimately convicted of arson. • Legal? Michigan v. Tyler • evidence was not properly collected and ruled it inadmissible • “entry to fight a fire requires no warrant, and that once in the building, officials may remain there for a reasonable time to investigate the cause of the blaze. Thereafter, additional entries to investigate the cause of the fire must be made pursuant to the warrant procedures” • the crime scene was not controlled by the police and left abandoned between searches allowing someone to potentially remove or tamper with any evidence Stop and Frisk Is it legal? • To be forced to complete a field sobriety test after being pulled over for suspected DUI? • Not Legal • To be forced to take a breathalyzer at the station or in the field to check the amount of alcohol in the body? • Not Legal • You can refuse, but it becomes probable cause for a search warrant to obtain a Blood Test Supreme court ruling… • Body’s Evidence: The US Supreme court has ruled that a person may be forced to take a blood alcohol test without their consent or search warrant as part of a vehicular investigation. The grounds for this decision was that the body, through its normal processes, works to destroy any alcohol consumed. Since the alcohol in the blood constitutes evidence related to potential criminal DWI or DUI actions, the body’s metabolism of the alcohol actually represents the destruction of evidence. Requiring a person to give blood alcohol evidence (blood sample usually) without a warrant or their consent is, therefore, admissible under the 4th Amendment. People v. Rosario • In 1961, the case of Rosario set a standard that requires statements by witnesses who testify (written, recorded, emails, etc.) be shared between both the defense and the prosecution. • The constitution forbids the prosecution from with holding any evidence related to the innocence of the defendant from the defense Day 1: Powerpoint of Crime Scene Basics • Review proper crime scene techniques and Watch videos Day 2: Search Patterns • Outdoor activity – Tape off 10ft x 10ft section using stakes and crime scene tape – Count paperclips in cup and scatter them in the 10ft x 10ft space – Using 4 kinds of search (line, grid, spiral, quadrant) collect as many paperclips as possible • Which is more effective for this type of exercise? Why? • Which search might be best to cover a small area? • Which search might be best to cover a large area? Day 3: Evidence Documentation: Notes and Sketching • Consider the four crime scenes. Make notes and sketch out the scene without collecting or disturbing the evidence!! • Use the proper measuring devices provided and make notes on the sheets given. • One sketcher, one note taker, one photographer, two measurers – Make sure to hand in your sketches, photographs and notes sheets to the commanding officer (Ms. Alfano) Day 4: Proper Collection of Physical Evidence • Now that you have completely documented the scene, you must bag and tag your evidence; be careful not to contaminate anything in the process!! • Make sure you use the proper receptacles according to the sheets you've been given! – Maintain chain of custody by properly documenting evidence bags and handing them in to your commanding officer (Mr. Beatty)