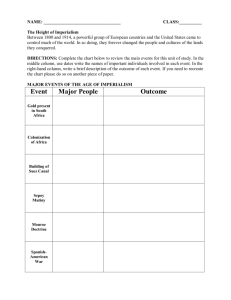

Grievances and the Genesis of Rebellion: Mutiny

advertisement