Why, who & how of nutrition education

advertisement

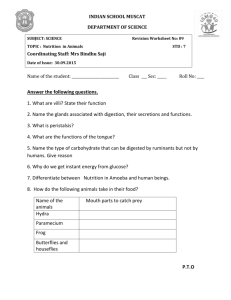

INTRODUCTION Thank you for taking the time to participate in this activity. As you will see from this presentation, effective nutrition counselling by GPs plays an important role in public health. This presentation contains 47 slides on nutrition counselling and education, and should take 1 hour to complete. During the presentation, you will be asked some questions. Please print the ‘answer sheet’ pdf (to open using hyperlink, place cursor over hyperlinked words, right click mouse and select ‘open hyperlink’) and record your answers on it. This activity is an RACGP-accredited Category 2 activity. To receive 2 Category 2 points, please print and complete the evaluation form. Please fax this and the completed answer sheet to Discovery Sydney (02 9925 3748). At the conclusion of this activity, there will be a short presentation (9 slides) on the role of chicken in a healthy diet. We hope the information will be of assistance to you when advising your patients about a healthy diet. NUTRITION COUNSELLING AND EDUCATION: WHY,WHO & HOW? Proudly sponsored by the Australian Chicken Meat Federation Inc LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Understand the importance of the GP’s role in providing nutrition counselling • Learn how to optimise patient nutrition counselling sessions • Consider system changes to improve the effectiveness of nutrition counselling in your practice PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Why is nutrition education important? • Who should deliver nutrition education? • What do GPs think and do about nutrition counselling? • How should nutrition counselling be delivered? • What are the obstacles to nutrition counselling? WHY IS NUTRITION EDUCATION IMPORTANT? • Established knowledge: nutrition plays an important role in the aetiology and management of many diseases affecting Australians1 • In 2003, a significant proportion of the burden of disease in Australia was directly attributable to nutrition2: Health risk Proportion of total burden (%) High body mass 7.5 Inadequate consumption of vegetables and fruit 2.1 High blood cholesterol 6.2 Reference: 1. National Public Health Partnership. Eat Well Australia. Canberra: Strategic InterGovernmental Nutrition Alliance (SIGNAL). 2001; 2. Begg S, et al. The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. PHE 82. Canberra: AIHW. 2007 PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Why is nutrition education important? • Who should deliver nutrition education? • What do GPs think and do about nutrition counselling? • How should nutrition counselling be delivered? • What are the obstacles to nutrition counselling? WHO SHOULD DELIVER NUTRITION EDUCATION? • GPs have the potential to decrease morbidity and mortality for many chronic diseases if they provide effective nutrition counselling1 • Reasons include: • GPs are public health agents who see 80% of the population each year2 • 54.7% of GP/adult encounters involve overweight or obese people3 • GPs are often long-term advisers who gain access to the daily lives and living conditions of all strata of the population4 • GPs are highly regarded as a reliable source of nutrition information5 Reference: 1. Eaton CB et al. J Nutr. 2003 Feb;133:563S-6S; 2. Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services (CDH & FS): General practice. Changing the future partnerships. Report of the General Practice Strategy Review Group. Canberra: Pine Printers, 1998; 3. Britt H, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2002–2003. AIHW Cat No GEP 14. Canberra: AGPS, 2003. 4. Watt GCM. BMJ. 1996;312:1026-9; 5. Worsley A. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53 Suppl 2:S101-7 GP AS IMPORTANT AS DIETICIANS IN NUTRITION COUNSELLING (1) • An Australian randomised control trial compared clinical outcomes in patients (N=273) with one or more chronic conditions (overweight, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes) • Interventions: – Dietician counselled: 6 sessions over 12 months – GP+dietician counselled: 6 sessions with dietician and GP reviewed progress in 2 of the 6 sessions, over 12 months – Control: no dietician counselling, usual care by GP Reference: 1. Pritchard DA, et al. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:311-6 GP AS IMPORTANT AS DIETICIANS IN NUTRITION COUNSELLING (2) Results: – Both intervention groups reduced weight and blood pressure compared with controls – Compared with patients counselled by dietician alone, patients counselled by GP+dietician were: • More likely to complete the intervention programme • Lost more weight (6.7kg vs 5.6kg) Reference: 1. Pritchard DA, et al. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(5):311-6 PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Why is nutrition education important? • Who should deliver nutrition education? • What do GPs think and do about nutrition counselling? • How should nutrition counselling be delivered? • What are the obstacles to nutrition counselling? WHAT DO GPS THINK AND DO ABOUT NUTRITION COUNSELLING? (1) • A survey of GPs showed 72% thought it was their responsibility to perform nutrition counselling1 • On average, in 10-15 min consultations, the time spent on nutrition counselling was found to be 1 min2,3 • In Australia, nutrition counselling is below a desirable level and/or national targets4 Reference: 1. Kushner RF. Prev Med 1995;24: 546–50 ; 2. Eaton CB, et al. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 23: 174–9; 3. Glanz K, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:89–92; 4. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2 nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 WHAT DO GPS THINK AND DO ABOUT NUTRITION COUNSELLING? (2) • A survey of GPs in NSW showed nutrition counselling was provided mostly for diabetes, lipid disorders and obesity1: Disease % of GPs who ‘strongly agreed’ to providing nutrition counselling Diabetes 79 Lipid disorders 71 Obesity 68 Ischaemic heart disease 46 Overweight 45 Hypertension 22 Reference: 1. Nicholas L, et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59 Suppl 1:S140-5 QUESTION 1 • The Australian study by Pritchard et al. showed that patients counselled by GP+dietician were equally likely to complete the intervention programme, compared with patients counselled by dietician alone True False PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Why is nutrition education important? • Who should deliver nutrition education? • What do GPs think and do about nutrition counselling? • How should nutrition counselling be delivered? • What are the obstacles to nutrition counselling? HOW SHOULD NUTRITION COUNSELLING BE DELIVERED? To maximise patient motivation and adherence: • Consider factors that increase the effectiveness of patient education • Take a patient-centred approach • Assess patient’s readiness to change: ‘stages of change’ model • Use motivational interviewing (These topics are covered in the following few slides) FACTORS THAT INCREASE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PATIENT EDUCATION (1) • A patient’s sense of trust in their GP1 • Face-to-face delivery2 • Patient involvement in the decisionmaking3,4 – See “A patient-centred approach” • Highlighting the benefits and costs5,6 – See “Motivational interviewing” Reference: 1. Trachtenberg F, et al. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:344–52; 2. Ellis S. Pat Educ Couns. 2004;52:97–105; 3.Mead N, et al. Patient Educ Counsel. 2002;48(1):51–61; 4. Rao J, et al. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1148–55; 5. Littel J, et al. Behav Modif. 2002;26:223–73; 6. Schauffler H, et al. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:62–8 FACTORS THAT INCREASE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PATIENT EDUCATION (2) • Strategies to assist patients remembering what they have been told1 e.g. patient leaflet, summarise goals at the end of the consultation • Tailoring information to the patient’s interest in change2 • Strategies that address the difficulty in adherence3,4 Reference: 1. Ley P. Patients’ understanding and recall in clinical communication failure. In: Pendleton D, Hasler J, editors. Doctor-patient communication. London: Academic Press, 1983; 2. Steptoe A, et al. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:265–9; 3. Rao J, et al. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1148–55 ; 4. Branch L, et al. Med Care. 2000;38:70–7 A PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH (1) A patient-centred approach involves1: – Actively involving the patient in the consultation – Respecting the patient’s autonomy – Encouraging the patient’s role in decision making – Embracing a more holistic approach that includes health promotion and disease prevention Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 A PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH (2) Encouraging more active patient involvement and inclusion in the consultation has a number of benefits: – Clarification of what is expected of you by the patient1 – Stronger patient autonomy, patient responsibility and patient self management2,3 – Increased patient and doctor satisfaction1 – Enhances the quality of communication4,5 – Better adherence to the recommended prevention activities5,6 Reference: 1. Grol R. Improving practice. A systematic approach to implementation of change in patient care. Oxford: Elsevier Science, 2004; 2. Shortell S, et al. Milbank Q. 1998;76:1–37; 3. Gold M, et al. J Fam Prac. 1990;30:639–44; 4. Tan S. The collaborative method: ensuring diffusion of quality improvement in health care: Report on the Collaborative Workshop, June 2003; 5. King L. Review of literature on dissemination and research on health promotion and illness/injury prevention activities. In: Sydney National Centre for Health Promotion, Department Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Sydney, 1995; 6. Ferrence R. Can J Public Health. 1996;87:S24–7 PATIENT’S READINESS TO CHANGE: ‘STAGES OF CHANGE’ MODEL (1) “The ‘stages of change’ model1 identifies 5 basic stages of change that are viewed as a cyclical, ongoing process during which the person has differing levels of motivation and readiness to change and the ability to relapse or repeat a stage. Each time the stage is repeated, the person learns from the experience and gains skills to help them move onto the next stage.”2 Reference: 1. Tenove S. Can J Nurs Res. 1999;31:95–9; 2. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 PATIENT’S READINESS TO CHANGE: ‘STAGES OF CHANGE’ MODEL (2) Adapted from RACGP ‘Green Book’2 Stages of change1: • Precontemplation: the person does not consider the need to change • Contemplation: the person considers changing a specific behaviour • Determination: the person makes a serious commitment to change • Action: change begins (large or small) • Maintenance: change is sustained over a period of time Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Red Book’ Taskforce. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 6th edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2005; 2. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 QUESTION 2 • Which stage of change is reflected in these comments? Patient comment “I don’t feel the need to adjust my diet” “I have started to drink water instead of soft drinks” “I think I should start reducing my salt intake” Stage of change MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING (1) • Definition: ‘a directive, patient centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping patients to explore and resolve ambivalence’1 • Motivational interviewing1: – Has been shown to be effective in a number of areas in the primary care setting, including nutrition and diet – Is a useful approach when patients show a degree of ambivalence Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING (2) Systematically directing the patient toward motivation to change Offering advice and feedback when appropriate Motivational Interviewing Selectively using empathetic reflection to reinforce certain processes Seeking to elicit and amplify the patient’s discrepancies about their health related behaviour to enhance motivation to change Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING STRATEGIES (1) • Regard the person’s behaviour as their personal choice – Ambivalence is normal • Let the patient decide how much of a problem they have – Explore both the benefits and costs associated with the problem as perceived by the patient – Encourage the patient to rate their motivation to change out of 10 and explore how to increase this score Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING STRATEGIES (2) • Avoid arguments and confrontation – Confrontation, making judgments or moving ahead of the patient generates resistance and tends to entrench attitudes and behaviour • Encourage discrepancy – Change is likely when a person’s behaviour conflicts with their values and what they want – The aim of motivational interviewing is to encourage this confrontation to occur within the patient, not between the doctor and patient – Highlighting any discrepancy encourages a sense of internal discomfort (cognitive dissonance) and helps to shift the patient’s motivation – When highlighting the discrepancy, in the first instance, let the patient make the connection Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 QUESTION 3 What are the four components of motivational interviewing? (Insert the correct words in the spaces below. Record your answers on your answer sheet.) WORDS: motivation, elicit, advice, discrepancies, feedback, empathetic, amplify, processes, change, systematically. i. ii. iii. iv. ________directing the patient toward _______to change. Seeking to ______and ______the patient’s __________about their health related behaviour to enhance motivation to ______. Selectively using _______reflection to reinforce certain _________. Offering ______ and _______when appropriate. THE 5-STEP MODEL An effective way to incorporate the elements of nutrition counselling presented in the last few slides is to use the 5As1,2: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Ask (or address) Assess Advise Assist Arrange Reference: 1. Ockene I, et al. Arch Intern Med 159:725-31; 2. RACGP National Standing Committee. SNAP: A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2004 CASE SCENARIO: USING THE 5As 1. Address the agenda: “Your blood test results show your cholesterol levels have increased substantially since your last test. I think we should review your eating habits and try to make some improvements.” Reference: 1. Ockene I, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725-31 2. Assess patient’s readiness to change and relevant diet experience: “How do you feel about making some changes to your diet?” “Can you think of some recent changes in your eating habits that may have contributed to the rise in cholesterol?” 3. Advise: “Based on your health risks and current diet, let’s focus on lowering your fat intake and adding a few more vegies to your diet.” “To help you understand how important this is for your heart, I’ll tell you about a study that was done in America a few years back. The study looked at about 45,000 men over an 8-year period. They found that those who were most likely to develop heart disease ate more red meat, processed meat, refined grains, sweets, French fries, and high-fat dairy products. In comparison, the group that had the lowest risk of heart disease ate more vegetables, fruit, legumes, whole grains, fish, and poultry.1” Reference: 1. Hu FB, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72: 912-921 “Here are some information sheets to get you started. On the back, there are suggestions about how you can reduce your fat intake and other healthy eating habits.” Reference: 1. National Heart Foundation of Australia. Dietary fats and heart disease. 2004. Available at: http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/document/NHF/nrcr_diet_fats_mar04.pdf; 2. myDr.com.au. Eating for a healthy heart. Available at:: http://www.mydr.com.au/default.asp?article=3105 “I’m going to give you some fill out at home…This is something that I get my patients to fill out when they have to change their behaviour. It’s called a decision balance. Think about what you would like and dislike about not making any changes to your diet and then do the same for making changes. It helps you to weigh up the pros and cons. We can talk about your answers when you bring it back at your next visit.” Decision Balance1 Like Dislike Stay the same e.g. get to eat what I want, tastes nice e.g. continue increasing my health risks Change (e.g. changing diet) e.g. better for my heart e.g. inconvenient to and overall health, lose prepare food, always weight? having to think about what I eat Click here to open and print a blank Decision Balance form, which you can give to your patients Reference: 1. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 4. Assist: “How about we try to start with two or three of these Heart Foundation recommendations.1” “Which of these do you feel you are most likely to stick to?” “What do you think will be the main difficulties in changing your diet?” Reference: 1. National Heart Foundation of Australia. Dietary fats and heart disease. 2004 5. Arrange follow-up: “If you feel you need more help, I can refer you to a dietician.” “Otherwise, I’d like to see how you’re going in about a month’s time.” PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Why is nutrition education important? • Who should deliver nutrition education? • What do GPs think and do about nutrition counselling? • How should nutrition counselling be delivered? • What are the obstacles to nutrition counselling? WHAT ARE THE OBSTACLES TO NUTRITION COUNSELLING? Lack of time Lack of confidence Lack of knowledge Common obstacles identified by GPs Financial obstacles Patients’ attitudes Reference: 1. Nicholas L. Aus Family Phys 2004;33:957-9; 2. Judd H, et al. Management of obesity in general practice: Report from the nutrition fellowship 1987. Sydney, Australia: RACGP, 1988. OVERCOME OBSTACLES THROUGH PRACTICE ORGANISATION (1) The above obstacles can be overcome to some extent by the development of a preventive program that includes1: – Setting practice priorities – Listing what roles each practice member currently undertakes and how nutrition counselling can be integrated into existing roles and responsibilities Reference: 1. RACGP National Standing Committee. SNAP: A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2004 OVERCOME OBSTACLES THROUGH PRACTICE ORGANISATION (2) – Reviewing the way in which appointments and follow up are arranged – Establishing information systems to support nutrition counselling (e.g. updating and managing tools and patient education materials) – Conducting ongoing quality improvement programs (e.g. audits) – Developing links with local services (e.g. dieticians) Reference: 1. RACGP National Standing Committee. SNAP: A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2004 FINANCIAL INCENTIVES (1) Interventions for behavioural risk factors, such as nutrition, can be part of a successful business model for GPs. It can be an attractive component of practice programs to encourage patients to attend the practice.1 Reference: 1. RACGP National Standing Committee. SNAP: A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2004 FINANCIAL INCENTIVES (2) There are a number of commonwealth programs that may help provide financial support. These include: – Practice Incentive Program (PIP) incentives to incentives for establishment of chronic disease register and recall systems (www.hic.gov.au/providers/incentives_allowances/pip/new_incentives.h tm) – The program to help fund practice nurses in rural practices (www.hic.gov.au/providers/incentives_allowances/pip/new_incentives/n urse_incentive.htm) – Under Medicare, EPC care planning services attract a Medicare rebate. An EPC multidisciplinary care plan may only be provided to patients with at least one chronic or terminal medical condition AND complex care needs requiring multidisciplinary care from a team of health care providers including the patient’s GP (www.health.gov.au/epc/careplan.htm) QUESTION 4 i. ii. iii. How often do you assess diet in patient’s with health risks? How often do you provide verbal nutrition advice to these patients? How often do you offer referral for nutrition counselling? Answers to be indicated on answer sheet as: Very frequently Frequently Sometimes Rarely Don’t know QUESTION 5 What types of patient education materials does your practice have concerning nutrition? (Tick all applicable) A. B. C. D. E. Pamphlet/booklet Computerised leaflet (e.g. pdf files) Posters Videos Other QUESTION 6 What proportion of your patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds are able to read and/or understand the patient nutrition information materials? Answers to be indicated on answer sheet as: All Most Some Few Don’t know QUESTION 7 Think of two changes that you can make to your practice systems to better support or improve the effectiveness of nutrition counselling sessions. Write these down in the space provided. SUMMARY • Nutrition plays an important role in the aetiology and management of many diseases affecting Australians1 • GPs, along with dieticians, are at the forefront of providing nutrition management in Australia2 • In Australia, nutrition counselling is below a desirable level and/or national targets3 • When counselling about nutrition, use strategies and tools that maximise patient motivation and adherence4 • Some obstacles to effective nutrition counselling can be overcome through practice organisation4 • There are financial incentives for the management of behavioural risk factors4 1. National Public Health Partnership. Eat Well Australia. Canberra: Strategic Inter-Governmental Nutrition Alliance (SIGNAL). 2001; 2. Nicholas L. Aus Family Phys 2004;33:957-9; 3. RACGP ‘Green Book’ Project Advisory Committee. Putting prevention into practice: Guidelines for the implementation of prevention in the general practice setting. 2nd edn. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2006 ; 4. RACGP National Standing Committee. SNAP: A population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. South Melbourne: RACGP. 2004 THANK YOU FOR COMPLETING THIS ACTIVITY! The next few slides will highlight the role of chicken in a healthy diet. We hope this update is useful when advising your patients. Printable PDFs of patient education materials are available at the end of this presentation. THE ROLE OF CHICKEN IN HEALTHY DIETS CHICKEN DELIVERS IMPORTANT NUTRIENTS Lean chicken meat: Delivers essential vitamins and minerals An excellent source of protein Over 55% of the total fat content is unsaturated fat Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au HOW DOES LEAN CHICKEN COMPARE WITH OTHER LEAN MEATS? Stir-fried lean chicken breast has the lowest total fat content compared to other meat sources Stir-fried lean chicken breast contains more than 55% unsaturated fatty acids Stir-fried lean chicken breast provides higher amounts of niacin equivalents than other lean stir-fry cuts of meat Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au CHICKEN CONTRIBUTES TO NUTRIENT REQUIREMENTS Lean chicken breast provides >50% RDI of protein for most people Lean chicken breast is a good source of magnesium and zinc for pre-pubescent children Baked lean chicken breast provides 110–147% of daily niacin requirements Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au Lean chicken for cardiovascular health A diet that emphasised chicken and fish, rather than red meat, and included nuts, low-fat diary products and high proportions of fruit and vegetables, was shown to be effective in lowering blood pressure, particularly in people with hypertension.1 Reference: 1. Sacks FM, et al. Clin Cardiol. 1999 Jul;22(7 Suppl):III6-10. POULTRY CONSUMPTION IS INCREASING IN AUSTRALIA 1 Reference: 1. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics, ABARE Australian Commodity Statistics, 2007 BUSTING THE MYTHS ABOUT CHICKEN (1) • Size: Through generations of selective breeding and careful attention to optimal nutrition, today’s chickens are faster growing, larger and stronger birds • No added hormones: Hormones are not administered in any form. Hormone use in growing chickens has been banned in Australia for many decades • Responsible use of antibiotics: Antibiotics are used to prevent and treat disease and their use is carefully managed to minimise development of resistance and to ensure no residues are detectable in meat. (Avoparcin and vancomycin are not used by the Australian chicken meat industry) Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au BUSTING THE MYTHS ABOUT CHICKEN (2) • No cages: Meat chickens are free to roam on the floor of large sheds – they are never caged • Organic and free range production: Free range and organic chickens are also housed in sheds but may also roam outside the shed for part of the day. Organic and free range chickens are not given antibiotics. Organic chickens are only given feed that is certified organic • Australian grown: Except for a small proportion of fully cooked tinned or retorted product, all chicken available for purchase in Australia is grown in Australia Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au CHICKEN AND AVIAN INFLUENZA • In recent years a highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza, H5N1, an animal disease, has spread widely among poultry in Asia and some other countries, but not in Australia. • The likelihood of an outbreak of this strain of AI in Australian poultry is extremely low. • This strain is highly unusual amongst avian influenza strains, in that, under exceptional circumstances, it can infect humans. • A high level of preparedness and past experience with AI outbreaks provide confidence that should the H5N1 strain, or any other AI strain, get into a local flock, it would be identified and eradicated quickly. • In the event of an outbreak in Australian poultry, chicken meat from infected birds would not reach consumers. • AI cannot be contracted by eating cooked poultry as the virus would be destroyed during normal cooking. Reference: 1. Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? www.chicken.org.au THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION Please remember to complete your answer sheet and evaluation form and fax to: Discovery Sydney (02) 9925 3748 PRINTABLE PDFs • • • • • • • Answer sheet Evaluation form Decision Balance form The Facts About Chicken: A Patient’s Guide Fact Sheet: Busting the myths about chicken Fact Sheet: Food Safety Food, Health and Nutrition: Where Does Chicken Fit? • The Facts About Chicken: A Dietitian’s Guide • www.chicken.org.au