Themes, Meanings And Style

advertisement

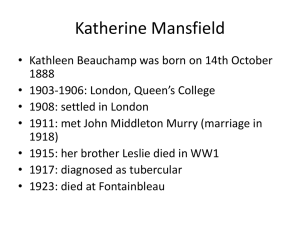

Themes And Meanings: The central theme in Katherine Mansfield's story is the cruelty of class distinctions. Mansfield was born in New Zealand when the country was still a British colony in which class distinctions were rigidly maintained. Her bestknown short story, “The Garden Party,” also deals with this subject. The reason that the rich Burnell children attend a school along with workingclass children such as the Kelveys is that they live in rural New Zealand, where there are no other nearby schools. These same characters also appear in other Mansfield stories, including “Prelude” (1917). There are biographical parallels between the Burnell family and Mansfield's own Beauchamp family, and also between Kezia and the young Kathleen (later Katherine) Mansfield. Mansfield attended a rural New Zealand school in which she encountered class distinctions; according to Antony Alpers, in Katherine Mansfield: A Biography (1953), Mansfield modeled her fictional Kelvey girls on Lil and Else McKelvey, the real-life daughters of a washerwoman. It is possible that Mansfield—like Kezia—tried to stand up for these girls in school. Mansfield uses this theme as a vehicle for a stinging portrait of the cruelty that was directed toward lower-class children. This portrait also contains a more sinister allusion to the pleasure that people, children and adults alike, derive from abusing those less materially fortunate. Not only are the Kelvey sisters shunned by their schoolmates, but even their teacher has a “special voice for them, and a special smile for the other children.” When the girls at school tire of the dollhouse, they look for fresh amusement by inciting Lena Logan to abuse the Kelveys verbally, taunting them about their future and their father. This makes the little rich girls “wild with joy.” After Aunt Beryl abuses the Kelvey girls, shooing “the little rats” from the dollhouse in the courtyard, she happily hums as she returns to the house, her bad mood dispersed. “The Doll's House” is a disturbing story of a society in which snobbery and cruelty are regarded as acceptable behavior. It is ultimately redeemed by Kezia's attempt at kindness; however, it is uncharacteristic of Mansfield's stories to end happily. Style And Technique: Mansfield aspired to write the perfect short story and her writing was influenced by the Russian writer Anton Chekhov. Like jewels, her stories exhibit many facets and are complex and luminous. She is skillful in deft character portrayal, creating powerful impressions with metaphor, and manipulating reader responses with a few apt words. Her description of Else Kelvey is an example. By frequently calling the girl “Our Else,” she enlists the reader's sympathies: “She was a tiny wishbone of a child, with cropped hair and enormous solemn eyes—a little white owl.” In her white “nightgown” of a dress, Else is a spectral image, perhaps a sad angel. She seems to be not quite of this world, and nobody has ever seen her smile. It is primarily through Else that readers experience the cruelty of the other children and adults. Mansfield uses the doll's house itself as a metaphor for the world of the rich upper class and creates a symbolic language surrounding it. The dollhouse opens by swinging its entire front back to reveal a cross section: “Perhaps it is the way God opens houses at dead of night when He is taking a quiet turn with an angel.” It is through Else's eyes that the reader sees into this world that normally would remain brutally closed to a poor child. The little amber lamp that Kezia loves comes to represent what is real, or of real value, in an otherwise desolate emotional world. It is apparently the description of the lamp that Else overhears that emboldens her to ask Lil to go see the dollhouse against Lil's better judgment. The final view of the Kelveys after seeing the dollhouse, resting together on their way home, picks up on the spiritual overtone in the story. Beryl's cruelty is forgotten. The “little lamp” that Else has seen, a symbol for Kezia's kindness and human warmth that defies the inhumane tyranny of class distinction, is a light that shines in the darkness of the life of this child. Something “real” is redeemed as Else smiles her “rare smile” at the end of the story.