Tradeoff Disad - WFI 2012

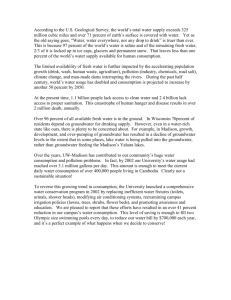

advertisement