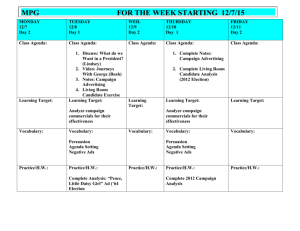

Campaign Finance Outline

advertisement

Campaign Finance Outline Theories of Democratic Governance 1) Factions, 3-11 a) James Madison, The Federalist Papers, No. 10 b) Faction – Has some “common impulse of passion or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens or to permanent interests of the community” i) How do we know what the “permanent interests” are? (1) Couldn’t get specific, cited paper money as adverse to public interest ii) Could this just be self-interested rhetoric? (1) Madison may have wanted to simply keep his landed money, power 2) Citizens and Representatives, 11-14 a) Edmund Burke, Speech to the Electors of Bristol i) Duty is to the nation as a whole, not your constituents (1) Fundamentally different from being an ambassador of a country ii) You owe your constituents your judgment iii) No duty owed to any subgroup or distinct interest 3) Pluralism and Progressivism, 14-23 a) Richard J. Ellis, Pluralism i) Argues that government actors and institutions are largely autonomous of one another, and we cannot speak of “the state” as a unitary actor (1) It is not a lack of autonomy that justifies refraining from reference to “the state”, but a lack of coherence between the various moving parts of the government ii) Argues against “neo-statists” by saying pluralists are not overly society-focused (1) Believes this focus is appropriate for understanding politics, democracy iii) Pluralists see the state as passively acted upon by various interests of society iv) It is not the autonomy of “the state” that pluralists emphasize, but of individual political actors 4) Legal theories on government regulation in a democracy a) Legal formalists i) Political branches cannot be allowed to interfere with liberties (1) There is no compromising in this category ii) Politics by its nature implicates deal making, bargaining, tradeoffs (1) Liberties cannot be subjected to this process b) Legal realists i) The law must be practical (1) Focus on abstract “liberties” doesn’t get us anywhere ii) This theory became ascendant in ~1937 (1) Marks a transition where courts began to defer to the legislature to decide what role government should play in meeting citizen needs and defending liberties (2) Austin v. MI Chamber of Commerce is clearest expression of this theory (a) Court focuses on practical effect of corporate money, not formalities of First Amendment jurisprudence on corruption iii) Citizens United represents serious pivot away from this approach (1) Court again willing to step in, define liberties itself History of Campaign Finance Regulation 1) Founding-1830s 1 a) Money not really a factor b) Elections dominated by small group of monnied elites c) Candidates ran on their reputation 2) 1830s-1880s a) campaigns financed by those seeking civil service positions 3) 1880s-1970s a) Pendleton Act i) President Garfield assassinated by disgruntled campaign contributor who didn’t get civil service position, prompts reform ii) Patronage system effectively eliminated (1) Ends politicization of current federal workforce? b) Corporate contributions banned (1925) i) Later extended to all corporate and union spending 4) 1970s-present a) Federal Elections Campaign Act (FECA, 1974) i) By far the most comprehensive regulation of campaign finance at the time (1) Response to Watergate, associated campaign finance scandals ii) Four principle components: (1) Contribution/expenditure limits (a) Contribution and expenditure limits were originally seen as serving relatively equal and complimentary purposes (2) Special restrictions (a) Particular persons and organizations (b) Corporations and unions (c) Government contractors (i) No contributions during formation to completion of contract (ii) Can form PACs (d) Foreign nationals (3) Disclosure (4) Public funding (a) Presidential Public Financing system (i) Was effective until 2008 b) Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA, 2002) i) Response to rise of “soft money” in 1990s (1) Loopholes let parties accept unlimited money, often exchanged for influence (2) Also responding to preponderance of “faux issue ads” ii) Banned soft money, capped contributions to the parties (1) Also closed roundabout avenues via state parties, ect. iii) Established new test for what speech would be regulated: “Electioneering Communications” (1) Focused on the district where a candidate was running at the proximity of the advocacy to an election (30/60 day window) (2) Attempt to broaden the “express advocacy” standard then in place iv) Raised contribution limits to candidates to sweeten the deal for legislators Bribery 1) Elements of bribery: a) Public official b) Corrupt intent i) Refers to the expectation that the gift or benefit will influence the official’s conduct in 2 a manner beneficial to the donor ii) Will be read into bribery statutes where not present (State v. O’Neill) c) Anything of value i) The benefit received may be… (1) A political benefit (a) Campaign contributions (even if otherwise legal) (b) An endorsment? (open question) (c) Votes for plant authorization and public financing (Dickinson v. Van de Carr) (2) To a third party (3) Other non-cash incentives (a) Loans to an official, (b) business transactions resulting in sales commission (c) numbers in an illegal lottery d) Intent to influence i) Does NOT require definitive quid pro quo (1) But see United States v. Brewster (suggesting the opposite in bribery cases) (2) Sometimes defined as “consideration” ii) Issue: how specific is the influence sought by the contributor? (1) Intent clearly shown where defendant sought a height variance for his hotel (State v. Agan) iii) Issue: how explicit is the agreement? (1) There is a violation “only if the payments are made in return for an explicit promise or undertaking by the official to perform or not to perform an official act.” (McCormick v. United States) iv) Speech or Debate Clause (1) When members of congress are indicted, the prosecution’s case may not depend on either legislative acts or the motivation for legislative acts v) A campaign contribution by a person with business pending before the official is not sufficient to demonstrate intent (1) Agricultural trade association to Sec. of Agriculture (Sun-Diamond Growers of California) (2) State legislator to organization of foreign medical graduates (McCormick v. United States) e) Official act i) How do we draw a line between public and private acts? ii) Requires control over the relevant thing sought (1) A state legislator’s influence over the liquor licensing process is not sufficient (State v. Bowling) iii) Acts “outside the formal legislative process” may be official acts (1) Attempts to promote specific business ventures in Africa (United States v. Jefferson) 2) Federal bribery statute (18 U.S.C. §201(b): a) Whoever--i) Directly or indirectly, corruptly gives, offers or promises anything of value to any public official… or offers or promises any public official… to give anything to any other person or entity, with intent--(1) To influence any official act; or (2) To influence such public official… to commit… or allow, any fraud… on the Unites States; or (3) To induce such public official… to do or omit to do any act in violation of the lawful duty of such official person…; 3 ii) Being a public official… directly or indirectly, corruptly demands, seeks, receives, accepts, or agrees to receive or accept anything of value personally or for any other person or entity, in teturn for: (1) Being influenced in the performance of any official act; (2) Being influenced to commit… or allow, any fraud… on the United States; or (3) Being induced to do or omit to do any act in violation of the official duty of such official…; b) Shall be fined… or imprisoned… or both 3) Elements of an unlawful gratuity (18 U.S.C. §201(c)): a) Whoever, in the discharge of an official duty… i) Gives offers or promises anything of value to any public official for or because of any official act performed or to be performed ii) Being a public official, demands, seeks, receives, accepts, or agrees to receive the same b) Shall be fined… or imprisoned… or both c) Requires “nexus” between the gratuity and a specific public act by the official i) Indictment that does not link a gratuity to a matter under a Secretary’s review cannot sustain an illegal gratuity conviction (United States v. Sun-Diamond Growers of California) 4) Theories of bribery a) Law v. Politics (Justice Frankfurter) i) Things that are law belong to the judges (1) Property, money, right to contract, due process, economic liberties ii) Public policy belongs to politics (1) Redistricting, voting procedures, campaign finance (2) Totally fine to make deals, weigh interests iii) Clear demarcation will make it more likely that judge’s orders will be followed Sennott v. Rodman & Renshaw – Sennott gets defrauded by agent of financial firm over period of months. Court says firm not liable because they didn’t do anything to suggest agent was their agent, and because Sennott ignored clear signs that agent was not legit. Baseline Issues/Themes 1) What is corruption? a) Continuum of corruption (further down = greater concern with the donor): i) Bribery ($$$ in pocket) ii) Quid pro quo iii) Too compliant (SAO) iv) Improper/undue influence v) Corrosive and distorting vi) Too compliant (LS vii) Inequality b) Competing definitions: i) Tight – “quid pro quo” (1) Leading cases: (a) Buckley, WRTL, Citizens United (b) Justices Scalia, Thomas, Kennedy (2) Pluralism theory (a) Society is best served by allowing competing interests to speak for themselves and let the chips fall where they may (b) We should encourage elected officials to be responsive to the desires of citizens 4 ii) Broad – “undue influence” (1) Leading cases: (a) McConnell v. FEC, (b) Justices Ginsberg, Kagan (2) Prevent donors from “calling the tune” (3) Civic republican theory (a) Promote individual participation in the political process (i) Idealized version is the Greek city-state (b) Regulate campaigns to the extent that individuals might be discouraged by the outsized influence of others iii) Broader still – “corrosive effect of large sums of money that has nothing to do with public support” (1) Leading cases: (a) Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (b) Justice Stephens (2) Is this equality, even though court doesn’t say so? (3) Descriptive theory (a) Government should look like the general population (b) Regulations should ensure that everyone gets a roughly equal say in elections (not limited to vote) to ensure no constituency has disproportionate power c) Court rejects argument that bribery statutes are the limit of what government can do to limit campaign finance (1) Hard to define what is a bribe, what should be called a crime 2) What is the scope of permissible government regulation? a) Court draws distinction between Issue Advocacy and Election Advocacy i) Not constitutionally mandated (1) “Advocacy of the election or defeat of candidates for federal office is no less entitled to protection under the First Amendment than the discussion of political policy generally or advocacy of the pass or defeat of legislation.” (Buckley) ii) defines the limits of speech which the government may regulate because of its potential to corrupt (1) because speech in the political context is so vital, laws will be invalidated as overbroad if they regulate the discussion of issues along with advocacy for a candidate b) Election advocacy (“express advocacy”) i) Became a major issue with the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) (1) Congress tries to expand its ability to regulate political ads by designating certain adds “electioneering communications” (a) Any communication that was expressly advocating for a candidate or the “functional equivalent” of such an ad ii) What is it? (1) Limited to speech “advocating for the election or defeat of” a candidate (2) Limited to speech that can be called “explicit advocacy” (Buckley) (a) Requires magic words: “vote for,” “elect,” “support,” “cast your ballot for,” “Smith for congress,” “vote against,” “defeat,” “reject” (b) Court explicitly rejects “relative to” language (Buckley) (3) Possibly includes the “functional equivalent” of express advocacy (a) Not clear if this was overruled by WRTL or Citizens United (b) Functional equivalent = whether advertisement was susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an advertisement supporting or opposing a candidate for office 5 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) (i) No reference may be made to the intention of the advertisers or the context of the advertisement iii) The courts determine whether a communication is express advocacy based upon a substance in communication standard, rather than an intent-based standard (Wisconsin Right To Life) (1) In Wisconsin Right To Life (WRTL) the Court overruled the BCRA provision banning “electioneering communications” 30 days before a primary and 60 days before a general election (a) “electioneering communications” were any that “refers to a clearly identified candidate for federal office” (b) Overruled McConnell v. FEC, which held that a blanket “blackout period” on electioneering communications 60 days before a general election or 30 days before a primary was permissible (2) Functional equivalent = whether advertisement was susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an advertisement supporting or opposing a candidate for office (a) No reference may be made to the intention of the advertisers or the context of the advertisement (3) But see Massachusetts Citizens For Life (MCFL) (a) EA not require magic words so long as effect is to advocate for election or defeat of clearly identified candidate. (i) Urging voters to vote for “pro-life candidate” and then providing names and pictures is EA. (MCFL) (4) WRTL essentially demands a bright line rule in this context, no room for inquiry into intent and context of ad c) Issue advocacy i) What is it? (1) Essentially any advocacy not captured by “express advocacy” definition What other distinctions make sense in the electoral context? a) Money v. volunteering i) Based on the equal capacity of each person to volunteer (1) Contrast with money, which is not available to us equally (2) But do we really all have equal time to volunteer? b) Type of speech v. identity of the speaker i) Is the context of the speech (ie political speech) the most important distinction? (1) Pluralist theory ii) Or is the speaker (corporation, individual, PAC) the real focal point? (1) Civic republican/descriptivist theory What is money in the electoral context? a) Why focus on money? i) Lowenstein – we have decided this is a poor basis on which to make a decision, kind of a gut reaction ii) Government decisions affect the distribution of resources, therefore those decisions must be made on ideas, absent pressure from money itself iii) Money can’t determine the distribution of money Can/should we regulate based on speaker’s identity? Can/should we regulate based on the context of the speech? Does “one person, one vote” principle have any place in campaign finance? Spending Limits/Bans (“expenditures”) 6 1) Leading case: Buckley v. Valeo a) Established distinction between expenditures and contributions that persists today i) Before case, no major distinction made (at least not by congress) 2) Burden: a) A direct speech restriction, and subject to the highest level of protection i) bars individuals from any significant use of the most effective modes of communication, substantial restraint ii) laws that provide advantages to your opponent based on your expenditures are a direct infringement on your speech (Davis v. FEC, Arizona Free Enterprise) b) Conceptions of expenditure regulation rejected by the Court: i) Argument: Campaign expenditures are conduct, and can be regulated by the government within reasonable limits (1) No, expenditures are speech, akin to burning draft cards in O’Brien ii) Argument: The expenditure ceilings regulate content, and are subject to reasonable time, place and manner restrictions (1) No, this is a blanket prohibition on speech, too broad to be condoned 3) Review: strict scrutiny a) Narrowly tailored… i) Limited to speech “advocating for the election or defeat of” a candidate ii) Limited to speech that can be called “explicit advocacy” (1) Requires magic words: “vote for,” “elect,” “support,” “cast your ballot for,” “Smith for congress,” “vote against,” “defeat,” “reject” b) …to serve a compelling governmental interest i) The government’s interest in preventing corruption or its appearance cannot justify expenditure limits (1) Court recognizes no link between expenditures and corruption (a) broad prophalactic is inappropriate in this case (2) Expenditures made independently of a candidate cannot be corrupting (Buckley) (a) this reasoning extends to Corporations and Unions (Citizens United) (i) overrules Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (holding corporate expenditures could be regulated in candidate elections because of the “distorting” influence of corporate money on the process (b) Court makes uncited assumption that independent spending is not very effective, or at least less effective than spending by a candidate (3) There is no threat of corruption from expenditures for or against a public ballot initiative (Bellotti) (4) There is no threat of corruption from a candidate spending large sums of his own money on a political campaign (Davis v. FEC) ii) The government’s interest in protecting shareholders cannot justify expenditure limits (1) Corporate law gives shareholders adequate recourse (2) Shareholders may always sell their interest (3) Deference to decisions by corporate officers of what is in the company’s interest is broad iii) The government’s interest in protecting candidates’ time to communicate with voters cannot justify expenditure limits (Randall v. Sorrell) iv) The government’s interest in preventing circumvention of valid campaign finance restrictions cannot justify expenditure limits (1) Exception: restrictions on expenditures coordinated with a candidate may be considered “in kind” and will be scrutinized as contribution limits (see Contribution Limits below) 7 (a) Party expenditures (Colorado Republican II) (b) Third parties (Landell v. Vermont PIRG (2d Cir. 2002)) v) Exception: in certain circumstances, the government has an interest in burdening expenditures through mandatory disclosure (see Disclosure below) vi) Exception: government can enforce expenditure limits when entered into voluntarily by candidates in exchange for public financing (see Public Financing below) 4) Scope of congress’s power to regulate expenditures (and all of campaign finance): a) Speech “advocating for the election or defeat of” a candidate b) Speech including “magic words” that indicate explicit advocacy of election or defeat of a candidate i) “vote for,” “elect,” “support,” “cast your ballot for,” “Smith for congress,” “vote against,” “defeat,” “reject” Contribution Limits 1) Leading cases: a) Buckley v. Valeo – What burdens and scrutiny apply to contribution limits? b) Colorado Republican II – when are expenditures more like contributions? c) Randall v. Sorrell – what outer limits apply on deference? What tests are applied? 2) Burden: a) speech by proxy, marginal restriction b) a major aspect of the right to contribute is the right to associate with the candidate or organization, which is essentially uninhibited by contribution limits (Buckley) i) The quantity of communication by the contributor does not increase perceptibly with the size of his contribution 3) Review: intermediate scrutiny a) Law must be closely drawn… i) In the normal case, the Court will not substitute its judgment for that of congress or state legislatures (1) Those bodies enjoy a natural expertise in this area ii) Contribution dollar level (1) The Court has “no scalpel to probe” what is the most ideal level for contribution limits (Buckley) (2) Laws overturned only when they reduce a candidate’s ability to speak to “below the level of notice” (Shrink Missouri) (3) Laws may be invalid if they prevent candidates from “amassing the resources necessary for effective advocacy” (Buckley, quoted in Randall) (a) Court looks to whether challengers can mount effective campaigns against incumbent officeholders (b) See “Evidentiary Standard” below iii) Coordinated expenditures (1) Limiting party expenditures coordinated with a candidate is closely drawn (Colorado Republican II) (a) Based on party’s unique influence over candidates iv) Timing of contributions (1) Ban on collecting contributions over one year before an election upheld (Thalheimer v. City of San Diego (9th Cir. 2011)) (2) Ban on large contributions in 21 days before an election struck down (Family PAC v. McKenna (9th Cir. 2012)) v) Residency requirements (1) Penalizing candidates who accept more than 10% of their funds from out-of-district 8 contributors struck down (VanNatta v. Keisling (9th Cir. 1998)) (2) Ban on campaign contributions by non-residents upheld (State v. Alaska Civil Liberties Union (Alaska 1999)) (a) Distinguished because VanNatta concerned limits that apply to residents of Oregon, unlike Alaska statute b) …to serve an important governmental interest i) The government’s interest in preventing corruption may justify limits on contributions to candidates (1) The government may ban contributions to candidates by certain entities which pose a particularly high risk of corruption: (a) Corporations and Unions (i) History of corruption combined with legal advantages that would make contributions to candidates inappropriate (ii) Reasoning extends to LLC’s and similar entities (Ognibene v. Parkes) (b) Government Contractors (2 U.S.C. §441(c)) (i) History of corruption combined with their clear interest in currying favor with the government ii) The government’s interest in preventing the circumvention of valid contribution limits may justify limits on contributions… (1) TO political parties (a) Congress may limit contributions to both state and national parties, without the option for unlimited gifts for non-political expenses (“soft money”), because of the significant potential for corruption of candidates in this context (McConnell v. FEC) (b) However, Court may require due deference to traditional role of parties in the democratic process (i) IE contribution limits to parties should be higher than to candidates, as in BCRA (2) TO organizations which contribute directly to candidates (a) NOTE: organizations may hold separate accounts and accept unlimited contributions for activities which do not involve contributing to or coordinating with candidates (IE administrative costs, independent expenditures) (Emily’s List v. FEC) (3) BY Corporations (a) Because a person may incorporate an infinite amount of entities, these could be used to circumvent contribution limits by sending many small contributions through various shell corporations (4) BY individuals (a) Aggregate annual limits on individuals are ok because many otherwise legal contributions to a party’s candidates poses a real risk of corruption iii) The government’s interest in preventing the appearance of corruption may justify contribution limits (1) Valid evidence of such appearance (Shrink Missouri): (a) Vote of citizens (for referendum), newspaper articles on corruption, isolated allegations of corruption (2) But see Kennedy in Citizens United: (a) “the appearance of influence/responsiveness will not cause citizens to lose faith in our democracy” (b) this is what democracy is premised upon (c) we WANT people to have this kind of influence over elected officials iv) The government’s interest in promoting citizen self-government may justify a 9 contribution ban (1) Foreign nationals (2 U.S.C. §441(e)) (a) Based on right to citizen self-government (b) Permanent non-resident aliens may contribute to campaigns v) The government has no interest in limiting contributions to organizations that do not contribute to candidates (1) The government has no interest in limiting contributions to an organization that makes only independent expenditures (SpeechNow.org v. FEC) (a) Reasoning extends to corporations and unions (2) The government has no interest in limiting contributions to an organization dedicated solely to influencing a ballot measure (Citizens Against Rent Control) (a) Presumably reasoning extends to corporations and unions, now that Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce is overruled c) Evidentiary standard: i) “The quantum of empirical evidence necessary to satisfy heightened judicial scrutiny of legislative judgments will vary up or down with the novelty and plausibility of the justification raised.” (Shrink Missouri) (1) Not a clear standard (2) This is a major issue with the court’s reasoning in these cases. ii) Deferential test (Shrink Missouri): (1) Court may rely on opinions of citizens, legislators, isolated incidents (a) 74% of Missourians want the law, affidavit my state legislator saying there is real danger of corruption, a few newspaper articles alleging improper practices (Shrink Missouri) iii) More exacting test (Randall v. Sorrell): (1) Threshold issue: are the limits lower than many other states and/or limits the Court has previously upheld? (a) Dollar for dollar (factor in inflation): (i) $1000 for federal congressional candidates (Buckley) (ii) $1,075 for state auditor in Missouri (iii)only 3 states with lower limits suggests limits are too low (Randall) (b) Ratio of the contribution to the size of the constituency (2) Five key factors considered when examining the record: (a) Does the law restrict challengers and/or protect incumbency? (i) Not average effect on elections but ability to mount effective challenge 1. Challengers will typically need more than the average candidate in order to overcome incumbency advantages, name recognition, ect. (b) What is the burden on parties and associations? (i) Applying the same contribution limits to parties as to all citizens suggests unconstitutionality 1. Limits parties’ ability to use their discretion and spend more in competitive races 2. Also reduces ability of contributors to the party to make a meaningful impact (c) Does the law inhibit volunteer activities? (i) Applying the cost of one’s volunteer activities to their contribution limit may severely limit one’s ability to engage in these activities (ii) Requiring volunteers to keep records of activities like miles driven, postage supplied, and pencils used may be a significant burden (d) Are limits indexed to inflation? (i) Limits on the borderline will become too low over time 10 (ii) Cannot rely on incumbent legislators to raise the limits (e) Does the jurisdiction have special justification? (i) Vermont does not have any special justification beyond other areas (ii) Court looks for history (recent or otherwise) of corruption in the state 4) How contribution limits function today a) Joint Fundraising Committee i) Donors may make a single large contribution that will be distributed to a candidate and his political party, in descending order, as contribution limits are met ii) Individual limits in 2012: (1) $5,000 to the candidate (presumably asking for the contribution) (2) $30,800 to national party (3) $40,000 to swing state victory fund (state party in swing states) iii) The practical effect is a $75,800 contribution to a candidate (1) Does this defeat contribution limits? b) Campaign strategy i) Campaigns essentially divide contributors into teirs (1) Small givers (law students) (a) Get $20 donation (b) Get them to volunteer (c) Advantage: low mainentance, send email blasts, ect (2) Larger givers (2nd year firm associates) (a) Contribute $2,000 directly to candidate (b) Maximum value reached by getting them to get some friends (in the firm?) to give the same amount (i) Multiplies total haul (3) Even larger (senior partners) (a) Focus on joint fundraising committee (i) Want full $75,800 contribution to JFC (4) “the clients” (millionaires/billionaires) (a) max out on $75,800 to joint fundraising committee (b) then you “introduce” these people to the super PAC guy ii) PROF – only need to deal with 35 or so people to raise $1,000,000 in hard money for candidate and the party (1) Only need a small addition of millionaires to reach $10,000,000 through super PACs Public Financing 1) Leading cases: a) Buckley v. Valeo – Presidential public financing system b) Arizona Free Enterprise Institute – triggered funds mechanism 2) Burden: a) Voluntary – marginal burden, as the candidate has the choice of avoiding the burden associated with state funds i) The amount of funding available is unlikely to make public funding coercive (1) Fact that much more funds were available through the Presidential public financing system was not conclusive of coercion (Republican National Committee v. Federal Election Commission) ii) Government funds which match private donations up to a certain level do not burden speech and are not evidence of coercion (Buckley) iii) Court will apply unconstitutional conditions doctrine: 11 (1) Government may enforce otherwise unconstitutional laws if they are entered into voluntarily b) Coercive – potentially heavy burden, as candidate has no realistic option but to accept the state-imposed burden on his/her speech i) Features suggesting coercion: (1) Speech by the candidate is burdened (a) A candidate’s speech results in additional funds for his opponent (2) Speech by others on the candidate’s behalf is burdened (a) An outside organization’s speech results in funds for their opponent (b) Contributions to the candidate are likely to lead to more money for the other side (3) Evidence the system seeks to “level the playing field” (a) System tries to give publicly financed candidates the same amount of money as their privately financed opponents ii) In this situation the government may not rely on the unconditional conditions doctrine because (1) there was a lack of meaningful choice on the part of the candidate, AND/OR (2) there was no choice on the part of contributors and independent spenders iii) if conditions are coercive, they are analyzed as if they were mandatory? 3) Scrutiny a) The level of scrutiny will vary up or down based on the burden placed on the first amendment rights of citizens, organizations and candidates b) Coercive system: i) What level of scrutiny would apply if the conditions were mandatory? (1) Conditions based on the level of campaign expenditures will receive strict scrutiny applicable to expenditure caps (Arizona Free Enterprise) (2) The government’s interest in a public campaign financing system that does not unduly drain the public treasury is insufficient (Arizona Free Enterprise) (a) But see Kagan’s dissent: these systems are valid, and government should have considerable discretion to make sure they work c) Voluntary system: i) Essentially a win for the government? 4) Types of systems: a) Funds grant from the government i) Block grant after demonstrating support (1) Signatures (2) Smaller contributions ii) Matching funds (1) Money based on what opponent and/or opposing organizations spend (2) Ruled unconstitutional in Arizona Free Enterprise v. Bennett iii) Given to candidate or party? (1) Party may distribute resources more productively than equal treatment of candidates (a) Ie parties more efficient with public money (b) Does this institutionalize party system? b) In-kind support (fundamentally similar to funds grant) i) Subsidize air time ii) Benefits: (1) Less drain on public funds iii) Downsides: (1) Government not good at knowing what is needed for campaigns 12 c) Tax breaks i) Deduction for contributions ii) Tax credit – lump sum deducted from liability iii) Downsides: (1) People who take advantage don’t need them (2) Lots of lost money for the government Campaign Finance Disclosure 1) Leading cases: a) Buckley v. Valeo – basic framework, government’s interests in candidate elections b) McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission – speaker’s name in anonymous leaflet regarding local tax proposal c) Doe v. Reed – petition signers in a statewide ballot initiative 2) Burden: a) “[L]east restrictive means of curbing the evils of campaign ignorance and corruption that Congress found to exist” (Buckley) i) Burden is less than limits on contributions and expenditures because there is “no ceiling” imposed on campaign-related activities ii) However, “compelled disclosure, in itself, can seriously infringe on privacy of association and belief guaranteed by the First Amendment” (Buckley) b) Any additional burden to minor parties and independents is insignificant (Buckley) c) Exception: the Court recognizes that in some circumstances the burden on a particular individual or organization will outweigh any government interest in mandating disclosure i) Test: would disclosure subject the organization to systemic harassment? (1) NAACP v. Alabama (2) Socialist Workers Party ii) Organizations meeting this threshold will be exempt from disclosure (1) Does not invalidate disclosure laws themselves 3) Scrutiny: “exacting scrutiny” a) Requires a government interest… i) Informational interest (valid) (1) Could inform candidates as well as voters (2) Individuals may prefer to vote by a candidates association with a particular organization ii) Anti-corruption interest (valid) (1) Interested parties may look for connections between campaign contributors or spenders and the candidates who benefit from the activity iii) Enforcement interest (valid) (1) Without disclosure it is easier to evade contribution limits, ect. iv) Other interests not mentioned by the Court (invalid or not ruled on yet): (1) Accountability (2) Preventing lies (3) Data accessibility (4) Equality (a) Will the Court count this interest against the constitutionality of the law? b) …holding a “relevant correlation” or “substantial relation” to the information required to be disclosed i) Name of the speaker (1) Insufficient government interest in requiring the disclosure of a speaker’s name in pamphlets addressing a campaign for school referendum (McIntyre v. Ohio 13 Elections Commission) (a) Identity of the speaker may change the message, make it less effective (i) Want to give people the opportunity to judge the issue on its own merits (b) Informational interest does not justify forcing the speaker to alter his/her own message (c) Interest in enforcement can be achieved by less broad/intrusive means (2) Required disclosure of petition signatures for ballot initiatives does not violate the speaker’s rights (Doe v. Reed) (a) Citizens exercising their right to legislate, must be accountable to the public in this circumstance ii) Amount being contributed (1) Anti-corruption and enforcement interests justify disclosure of amount of contributions (provided there is no problem with threshold) (Buckley) iii) Threshold for reporting (1) Without a record, thresholds will only be overturned if “wholly without rationality” (Buckley) iv) Amount of reporting (scope) (1) Only those communications that “expressly advocate the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate” (Buckley) (2) Communications in which citizens are participating in the legislative process (Doe v. Reed) 4) Disclosure requirements today a) Electioneering communications (BCRA § 434(f)(3)) i) Refers to… (1) broadcast, cable or satellite communications (2) referring to a clearly identified candidate (3) within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary (4) targeted to the district or state where the candidate is running ii) Requires… (1) Such communications to be paid for with “hard money” (a) IE money raised subject to contribution limits (2) Disclosure of the source of the funds (under certain conditions) (a) Criteria (i) Making ECs exceeding $10k in value in one year (ii) Disclosure required on first date where aggregate expenses exceed $10,000 (based on execution of contract, not disbursement per se) and at time of all subsequent disbursements (b) Information to be disclosed (i) Names and addresses of all contributors who contributed an aggregate amount of $1,000 or more during relevant period (ii) ID of person making disbursement (iii)Amount of disbursement and ID of recipient (if over $200) 14