AP Language and Composition Syllabus

advertisement

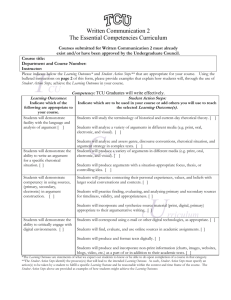

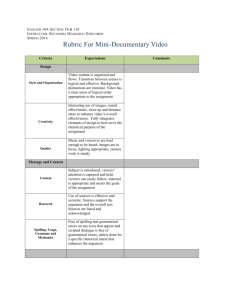

AP Language and Composition Course Syllabus 2013-14 Instructor: Ms. Mueller Room: D-111 Phone: 315-8289 E-mail: Nicole.mueller@nicolet.us Course Description: The AP course in English Language and Composition is designed for the student who desires a deeper understanding of the art that is written language. Through a curriculum composed of advanced writing theory combined with a wide sampling of gifted authors, students develop an awareness of rhetorical devices, learn how to tailor their communication for appeal to audience and format, and apply their word-craft to write for a variety of purposes. A skilled writer in an AP Language course draws from both personal experience and professional knowledge, and knows when and how to include both in her writing for greatest effect. As this course is intended to incorporate the skills taught in an elementary college writing course, emphasis will be placed on the decoding of challenging texts for both content and technique, the use of textual support to drive the development of written arguments, and the role levels of diction, syntactical structures, and connotative use of language play in crafting effective text. In English, please? Critical reading – establish purpose, identify tone, annotate text, evaluate effect. Recursive writing, with a focus on structural self-analysis (what the writer does rather than what the writer says). Expect to write – frequently, copiously. Expect to write and rewrite the same essay a number of times, each time with a different spin (change the point of view…change your verbs from simple to present progressive…change your tone by changing any five words). Expect to give – and get – feedback, from me, from your classmates, from yourself. Course work will include: Out-of-class assignments (reading/response; skill practice; other writing assignments) Five formal essays (note: each essay assignment encompasses all stages of writing process – prewriting/planning, draft, editing/revision—evidence for which must be submitted in order for assignment to receive credit) In-class practice of AP exam skills (multiple choice response to text, 40-minute ondemand responses) One research project in which the student generates, prepares materials for, and responds to a synthesis prompt. Literature circles, one per quarter. The first quarter will focus on memoir and may include the following texts: Heat by Bill Buford; The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston; Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt; An American Childhood by Annie Dillard; The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid by Bill Bryson; Colored People by Henry Louis Gates; and Paula by Isabel Allende. The second quarter’s reading looks at social/historical uses of non-fiction; students may choose among Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed, Jon Krakauer’s Where Men Win Glory; Barbara Tuchmann’s The Guns of August; Eric Weiner’s The Geography of Bliss; Lewis Thomas’s Lives of a Cell, Robert Kaplan’s Monsoon, and Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran. 1 Lit circles will contain no more than four members and are designed to give opportunities to practice the basic aspects of reading analysis but with greater student autonomy. The four roles are: discussion director; summarizer; rhetorical annotator; researcher. The discussion director formulates questions designed to both probe the content and extend the conversation; the summarizer will practice summary skills, writing a description that is both “concise and precise”; the rhetorical annotator will note the use – or lack thereof – of different rhetorical devices and analyze their effect; the researcher will be responsible for bringing in an outside source – an article or visual artifact – that touches upon or connects to a topic discussed in that day’s section of the text. (If a literature circle is comprised of only three students, the role of discussion director and summarizer will be combined.) A word on “homework”: I intend to run this course more like a seminar than a traditional class. If I assign a reading, I expect you to read, annotate, analyze, and come to class ready to discuss the ideas and rhetorical structure of the work, or to take notes on informative texts. You will know that you are mastering the class when I don’t have to ask prompting questions because your work with the text has anticipated what I would ask. Consequently, as homework is largely prep for the real work of the class, the discussions, it will be graded on a high passpass-fail scale. First drafts of written work will be graded on the same scale, for completion; final drafts will be graded either A, B, or re-do. In this class, you are graded based on the skills you demonstrate: you are either advanced or proficient – or you are getting the extra help you need and the extra practice you require to reach those levels. Grading: Summer Reading assignment: 5% Homework and minor writing assignments: 15% Revised essays: 50% Class participation/Lit Circles: 20% Synthesis project: 10% The course work will be worth 80% of your final grade, with the final exam worth 20%. Isn’t this where you list your classroom rules? You are upperclassmen – juniors and seniors. I don’t expect to have to tell you to not carry on personal conversations; not to eat in class; to use appropriate language and content in writing/speaking; not to cheat, copy, or plagiarize or it will receive a 0 and a referral; to come on time to class or we will make up that time after school; no hats/phones/i-whatsits/etc.; bring your materials to class; homework is due when it’s due and not taken late… so I won’t. But in return, I expect the mature and courteous behavior that I would expect in a man/woman about to enter the adult world. I prefer to give you the benefit of the doubt, but will intervene if I feel that the functioning of the class or the security of a student is being challenged. Do I need anything special for this class? A 3-ring binder w/looseleaf to store assignments, readings, revised work. A space for journaling: I prefer a composition notebook. Make sure it’s something you can turn in to me. Pens, pencils, quills, cuneiform wedges – something with which to write. A flash drive to save work done on the computer. Highlighters and post-its for on-text annotations. 2 One box of Kleenex, to save our noses during the winter cold season. The primary texts for the course are: Shea, et al. The Language of Composition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin Press, 2012. Lunsford, et al. Everything’s An Argument. New York: Bedford/St. Martin Press, 2009. DiYanni, Robert, and Pat C. Hoy II. Frames of Mind: A Rhetorical Reader with Occasions for Writing. New York: Wadsworth Publishing, 2008. 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology. Samuel Cohen, ed. New York: Bedford/St. Martin Press, 2010. Kolln, Martha, and Loretta Gray, Rhetorical Grammar. New York: Longman, 2009. UNIT OUTLINE UNIT 1: CRITICAL ANALYSIS IN READING AND RESPONDING (OR “THE TRICKS OF THE TRADE”) Essential questions: 1. What does it really mean to “read” a text? How is reading more than simply decoding? 2. What role does an author’s purpose and audience play in how s/he writes – and how I read? 3. Does it matter how you sequence an idea? 4. How you “read” a visual? 5. How does the context of a text – both the one in which it’s written and the one in which it’s read – impact its meaning? 6. We use lenses for “seeing” – how do we use “lenses” for reading? 7. What is the connection between how I read, and how I write? In this first unit, students will explore the ways in which they interact with a text. Areas for study will include idea development, organizational strategies and rhetorical techniques, the author-subject-audience relationship, and how context and purpose shape an author’s writing. Students will practice the steps of critical reading and annotation on a variety of linguistic/nonlinguistic texts, distinguishing between idea outlines and structural outlines. Using their annotations/structural outlines, students will practice writing a textual analysis with attention to the relationship between purpose and effective organization (theme-structure-technique). Students will also apply their reading skills to visual documents (print advertisement, commercial, photograph). Theory Readings: 1. Ch. 4, 5, 6, 10 In Kolln, Rhetorical Grammar 2. Ch. 2-3 – “Visual Understanding” and “Analysis” from Frames of Mind 3. Ch. 1, “Rhetorical Situation” and Ch. 2, “Close Reading” from The Language of Composition 4. Introduction (annotation and critical reading) from 50 Essays 5. Handout: “Says/Does” response (structural outlining) 3 Concepts discussed: “personal lens”, rhetorical context (subject/purpose/audience/ occasion or context), annotation, structural outline, summarization, close reading/critical analysis, dominant impression, reading a visual (perceptual/interpretive/iconographic, and peopleposture-POV-props-proportion-position), DIDLS and SOAPS Skills Practiced: marking the text; structural outlining, summarization and annotation, reading a visual. Readings: Annie Dillard – “Seeing.” How is this text also a text on how we read? “The Joy of Reading and Writing: Superman and Me” (Sherman Alexie) “Graduation” (Maya Angelou) “Once More to the Lake” (E.B. White) Travels With Charley, John Steinbeck (assigned as summer reading); excerpts from Log from the Sea of Cortez Selections from Blue Highways (William Least Heat-Moon), West With the Night (Beryl Markham) and texts by John Barry Students will begin their choice of memoir in lit circles UNIT 2: THE AUTHOR AS AUTHORITY: ESTABLISHING ETHOS Essential Questions: 1. What is the author’s responsibility to the reader? 2. What makes an author’s work trustworthy? Credible? Compelling? 3. How does how I say it impact how you read it? 4. Can a writer be both personal and professional? 5. Why do we write? In this unit students will explore the ways authors establish personal authority – through reliable, credible sources, through drawing upon personal experience and primary sources or first-hand accounts, through choosing tone and levels of diction carefully to match subject, audience, or purpose, and through skillful manipulation of language. Students will also discuss navigating the boundaries between personal opinion and professional discourse, and how to be aware of bias in text – both others’ and their own. As a part of the ethos discussion, students will learn to be aware of the sources of their own reading/research and how that source might affect the validity of the work under consideration. While all successful writing incorporates a sense of ethos, the focus for this unit will be narrative, descriptive, and definition/classification. Many of the readings/visuals in this unit deal with “coming of age moments”, including encounters with discrimination, the challenges of war, and the search for “truth” in a changing and often disillusioned world. Theory Readings: 1. Ch. 3, “Ethos”, in Everything’s An Argument 2. Ch. 4 & 5, “Description” and “Narration” in Frames of Mind 3. Ch. 8, “Arguments of Definition,” Everything’s an Argument 4. Ch. 19, “Evaluating and Using Sources,” Everything’s an Argument Concepts discussed: Vantage point; techniques of description (sensory language, action verbs, vivid adjectives, specific and concrete details, figurative comparisons, and vantage point); 4 sequencing of events (chronologically, by importance, central point); tone/identification of tone; satire; types of definition (inc. stipulative and extended); bildungsroman; epiphany, loss of innocence. Revisit “Reading a visual” Skills Practiced: Grammatical tricks for enlivening writing: nouns for clarity, verbs for action, absolutes for focus, appositives for expansion, participles for movement, and transitions to make it all hang together. Readings: “Shooting Dad” (Sarah Vowell) “Shooting an Elephant” and “Marakesh” (George Orwell) “How It Feels To Be Colored Me” (Zora Neale Hurston) “But Enough About Me” (Daniel Mendelsohn) Truth in writing? Criteria for “truth” drawn from “Sex, Drugs, Disasters, and the Extinction of Dinosaurs” (Stephen Jay Gould) and “The Ways We Lie” by Stephanie Ericsson Students will finish their chosen memoir in lit circles UNIT 3: THE AUTHOR AS “VOICE OF REASON”: LOGOS Essential Questions: 1. What’s the difference between reason and rationalization? 2. Can you admit weakness and still mount a strong argument? 3. Is all evidence equal, or do some types carry more weight than others? 4. How do we process information, and how does that shape how effective writers present their arguments? 5. When does structure/organization matter in writing, and when can we choose to deviate from that structure? 6. Do statistics lie? All writing uses both evidence and the logical presentation thereof to make its point; this unit focuses more minutely on writing that is driven not by the author’s personal experience but by a response to external evidence. As in the previous unit, students will continue to evaluate sources for validity and credibility. Writing tasks in this unit will continue the student’s exploration of critical analysis, and include a more narrow focus on process analysis, cause/effect, and comparison/contrast writing – types of writing chosen both for the strategies employed in their structure and for the shift in emphasis onto subjects not solely rooted in the author’s personal experience. Many of the readings/visuals in this unit deal with social issues that spark debate both for what causes them and for how they can be solved, including poverty, racism, and gender stereotyping. In keeping with this topic, many of the visuals for this unit bring in the political dimension in which we attempt to solve these problems and open up the debate as to how effective – or ineffective – political invective has become. Theory Readings: 1. Ch. 3, “Analyzing Arguments”, The Language of Composition 2. Ch. 4, “Arguments Based on Facts and Reason”, Everything’s an Argument 3. Ch. 20, “Documenting Sources,” Everything’s an Argument 4. Ch. 8, 9, 10 – “Comparison/Contrast, Process Analysis, Cause/Effect” in Frames of Mind 5 Concepts discussed: Types of examples; verifying and citing sources; avoiding plagiarism; traditional patterns of organization for comparison/contrast, cause/effect, and process analysis writing; varying patterns in response to needs of subject/audience; schemes of rhetoric; the difference between repetition and redundancy Skills Practiced: Schemes of rhetoric; parallelism, repetition, and coherence; citations/works cited (emphasis on MLA as school standard; introduction to APA and Chicago); Tolumin argument; block and alternating form in comparison/contrast writing. Readings: “History by the Ounce” (Barbara Tuchmann) – importance of evidence “On Dumpster Diving,” (Lars Eighner) “To Farm or Not To Farm” (Jared Diamond – example of cause/effect) “The Way To Reduce Black Poverty in America” (Henry Louis Gates, Jr.) “Behind the Curtain: The Body, Control, and Ballet” (Paula T. Kelso) Students will begin their social/historical non-fiction text in lit circles UNIT 4: THE AUTHOR’S HUMAN CONNECTION: PATHOS AND ARGUMENT Essential Questions: 1. How does an author “build a bridge” to his/her audience? 2. What is the difference between an impassioned argument and an irrational one? 3. How does the subject of a piece – or the audience – determine the level of emotional involvement appropriate from the author? 4. Must all argument end in division? 5. When is it okay – and not okay – to be funny? And what is “funny,” anyhow? All writing is argumentative in that it wishes to convince its audience of the worthiness of its subject. This connection is often made through “Argument,” however, in the current polarized environment, has become associated more with a heated exchange of ideas resulting in a stalemate. In this unit students will explore both classical and contemporary ideas of persuasion, the targeted use of all three appeals to change the mind or alter the perception of the reader. They will do so with a specific focus on the techniques used to appeal to the reader’s emotions, a tool which is at the same time effective and dangerous. At the same time, writing with a regard to the possible reaction of the reader, with humor or with sympathy, can also humanize a difficult argument and lead to greater sympathy for an opposing point of view. The goal of this unit, in addition to having students explore the structure of persuasive writing, is to have students develop their own sense of the appropriate/inappropriate use of emotional appeal, and, ultimately, a greater sense of/respect for their audience in their own writing. Theory Readings: 1. Ch.2, “Arguments from the Heart”, Everything’s an Argument 2. Ch. 13, “Humor in Arguments,” Everything’s an Argument 3. Ch. 17, “Fallacies of Argument,” Everything’s an Argument 4. Ch. 12, “Argument,” Frames of Mind Concepts discussed: The role of pathos in writing; the author’s tone, and how to modify tone for audience; allusion; tropes and figurative language; patterning an argument; the importance of the rebuttal. 6 Skills Practiced: sentence structure and created rhythm; using allusion to add depth to writing; use of tropes in writing; revision of phrases/clauses in conjunction with sentence structure and created rhythm. Readings: “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat/We Shall…/This Was” cycle of speeches (Winston Churchill) “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (Martin Luther King, Jr.) “Watching TV Makes You Smarter,” Steven Johnson “Average is Over” (Thomas L. Friedman Student choice – article from The Onion Students will finish their social/historical non-fiction text in lit circles 7