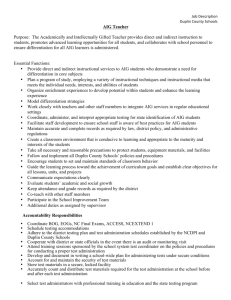

(AIG) plan - Wake County Public SchoolsAcademically or

advertisement