File - Bridget McHugh

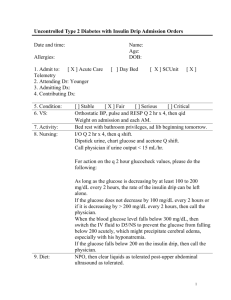

advertisement

Jones, Mitchell, Male, 63 y.o. Allergies: NKA Code: FULL Isolation: None Pt. Location: MICU Bed #5 Physician: R. Paulvart Admit Date: 5/12 Patient Summary: Mitchell Fagan is a 63-year-old male admitted with acute hyperglycemia. History: Onset of disease: Patient’s coworker became concerned when patient did not report to work or answer his phone when called. Coworker went to patient’s home and found him drowsy and confused. Took patient to ER, where patient was noted to have serum glucose of 1524 mg/dL. Medical history: Type 2 DM x 1 year—prescribed glyburide and metformin but admits that he has not taken the medications regularly; HTN; hyperlipidemia; gout Surgical history: ORIF R ulna; hernia repair Medications at home: Glyburide 20 mg daily; 500 mg metformin twice daily; Dyazide once daily (25 mg hydrochlorothiazide and 37.5 mg triamterene); Lipitor 20 mg daily Tobacco use: 1 ppd 3 20 years—now quit Alcohol use: 3–4 drinks per week Family history: Father—HTN, CAD; mother—type 2 DM Demographics: Marital status: Single Number of children: 0 Years education: 16 Language: English only Occupation: Retired military—now works as consultant to military equipment company Hours of work: 8-5 daily Household members: NA – lives alone Ethnicity: Caucasian Religious affiliation: NA Admitting History/Physical: Chief complaint: “I had a lot of vomiting that I thought at first was food poisoning but I just kept getting worse.” When questioned about medications, patient admits that he has not taken medications for the diabetes regularly—“I hate how they make me feel but I almost always take my other medications for blood pressure and cholesterol.“ General appearance: Mildly obese, 63-year-old male. Vital Signs: Temp: 100.5 Pulse: 105 Resp rate: 26 BP: 90/70 Height: 5'9" Weight: 214 lbs Heart: Regular rate and rhythm HEENT: Head: WNL Eyes: PERRLA Ears: Clear Nose: WNL Throat: Dry mucous membranes without exudates or lesions Genitalia: Deferred Neurologic: Alert but previously drowsy with mild confusion Extremities: Noncontributory Skin: Warm and dry; poor turgor Chest/lungs: Respirations are rapid—clear to auscultation and percussion Peripheral vascular: Pulse + 1 bilaterally, warm, no edema Abdomen: Active bowel sounds + 4; tender, nondistended Orders on Admission: 1. Replace 1 L NS stat. Then begin regular insulin. 1 unit/kg/h in NS 40 mEq KCl/liter @ 500 mL/ hr x 3 hours. Then regular insulin 1 unit/mL NS 10 mEq KCl/liter @135 mL/hr. Begin infusion at 0.1 unit/kg/hr = 3.7 units/hr and increase to 5 units/hr. Flush new IV tubing with 50 mL of insulin drip solution prior to connecting to patient and starting insulin infusion. 2. Labs: BMP Stat Phos Stat Calcium Stat UA with culture if indicated Stat Clean catch Bedside glucose Stat Islet cell autoantibodies screen Thyroid peroxidase abs TSH Comp metabolic panel (CMP); Hematology panel C-peptide Hemoglobin A1c 3. NPO except for ice chips and medications. After 12 hours, clear liquids if stable. Nursing Assessment 5/12 Abdominal appearance (concave, flat, rounded, obese, distended) Palpation of abdomen (soft, rigid, firm, masses, tense) obese Bowel function (continent, incontinent, flatulence, no stool) continent Bowel sounds (P=present, AB=absent, hypo, hyper) RUQ LUQ RLQ LLQ Stool color Stool consistency Tubes/ostomies Genitourinary Urinary continence Urine source Appearance (clear, cloudy, yellow, amber, fluorescent, hematuria, orange, blue, tea) Integumentary Skin color Skin temperature (DI=diaphoretic, W=warm, dry, CL=cool, CLM=clammy, CD1=cold, M=moist, H=hot) Skin turgor (good, fair, poor, TENT=tenting) Skin condition (intact, EC=ecchymosis, A=abrasions, P=petechiae, R=rash, W=weeping, S=sloughing, D=dryness, EX=excoriated, T=tears, SE=subcutaneous emphysema, B=blisters, V=vesicles, N=necrosis) Mucous membranes (intact, EC=ecchymosis, tense P P P P light brown soft NA yes clean specimen cloudy,amber pale DI poor intact intact A=abrasions, P=petechiae, R=rash, W=weeping, S=sloughing, D=dryness, EX=excoriated, T=tears, SE=subcutaneous emphysema, B=blisters, V=vesicles, N=necrosis) Other components of Braden score: special bed, sensory pressure, moisture, activity, friction/shear >18 = no risk, 15–16 = low risk, 13–14 = moderate risk, <12 = high risk) 20 Laboratory Results: Chemistry Chemistry Sodium (mEq/L) Potassium (mEq/L) Chloride (mEq/L) Carbon dioxide (CO2, mEq/L) BUN (mg/dL) Creatinine serum (mg/dL) Glucose (mg/dL) Phosphate, inorganic (mg/dL) Magnesium (mg/dL) Calcium (mg/dL) Osmolality (mmol/kg/H20) Bilirubin, direct (mg/dL) Protein, total (g/dL) Albumin (g/dL) Prealbumin (mg/dL) Ammonia (NH3, µmol/L) Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) ALT (U/L) AST (U/L) CPK (U/L) C-reactive protein (mg/dL) Cholesterol (mg/dL) HDL-L (mg/dL) LDL-C (mg/dL) LDL/HDL ratio Triglycerides (mg/dL) HgA1c (%) C-peptide (ng/dL) Ref. Range 5/12 1780 on admission 5/13/ 1522 136–145 3.5–5.5 95–105 23–30 8–18 0.6–1.2 70–110 2.3–4.7 1.8–3 9–11 285-295 <0.3 6–8 3.5–5 16–35 9–33 30–120 4–36 0–35 55-170M <1.0 120–199 > 55 F >45M <130 <3.22 F <3.55 M 35–135 F 40–160 M 3.9-5.2 0.51-2.72 131 ! 3.8 ! 101 27 31 ! 1.9 1510 ! 1.8 ! 1.9 10 360 ! 0.019 7.1 4.9 32 15 112 11 17 145 0.8 205 ! 134 ! 4.0 100 28 20 ! 1.3 ! 480 ! 2.1 ! 2.1 9.8 304 ! 55 ! 123 2.26 185 ! 15.2 ! 1.10 ICA GADA IAA Hematology WBC (x 103/mm3) RBC (x 106/mm3) Hemoglobin (Hgb, g/dL) Hematocrit (Hct, %) Urinalysis Collection method Color Appearance Specific gravity pH Protein (mg/dL) Glucose (mg/dL) Ketones Blood Bilirubin Prot chk WBCs (/HPF) Intake/Output NEG NEG NEG NEG NEG NEG 4.8–11.8 4.2–5.4 F 4.5–6.2 M 12–15 F 14–17 M 37–47 F 40–54 M 13.6 ! 5.7 — — — 1.003–1.030 5–7 Neg Neg Neg Neg Neg Neg 0–5 clean catch pale yellow clear 1.045 ! 5.0 ! 10 ! 1 ! Neg Neg Neg 1 ! 3–4 Date OUT 57 ! 5/12 0701– 5/13 0700 Time IN 14.2 0701–1500 NPO 2,175 1501–2300 NPO 1,080 2301–0700 NPO 1,080 Daily total 2,175 1,080 1,080 4,335 Urine 1,100 450 525 2,075 Emesis output Other Stool Total output 120 0 0 120 1,220 +955 +955 450 +630 +630 525 +555 +555 2,195 +2,140 +2,140 P.O. I.V. I.V. piggyback TPN Total intake (mL/kg) Net I/O Net since admission (5/12) 4,335 MD Progress Note: 5/13 0750 Subjective: Mitchell Fagan’s previous 24 hours reviewed Vitals: Temp: 99.6, Pulse: 83, Resp rate: 25, BP: 129/92 Physical Exam General: Alert and oriented to person, place, and time HEENT: WNL Neck: WNL Heart: WNL Lungs: Clear to auscultation Abdomen: Active bowel sounds Assessment/Plan: Results: –ICA, GADA, IAA, C-peptide with insulin level indicating T2DM but now requiring insulin at home Dx: Type 2 DM uncontrolled with HHS Plan: Change IVF to D5.45NS with 20MEq K @ 135 mL/hr. Begin Lispro 0.5 u every 2 hours until glucose is 150–200 mg/dL. Tonight begin glargine 19 u at 9 pm. Progress Lispro using ICR 1:15. Continue bedside glucose checks hourly. Notify MD if blood glucose >200 or <80. Consult dietitian for diet advancement, total carbohydrate Rx, and distribution. Consult diabetes education team for self-management training for patient after stabilized and when transferred to floor. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------R. Paulvart, MD Nutrition Interview on 5/13: Meal type: NPO then progress to clear liquids and then consistent carbohydrate-controlled diet Fluid requirement: 2000–2500 mL after rehydration History: Patient states that he really doesn’t follow any strict diet except for not adding salt—tries to avoid high-cholesterol foods and stays away from “sugar”. Typically eats 2 meals a day. Most recently he had experienced vomiting for approximately 12–24 hours and so had not eaten anything and only had sips of water. He has never seen anyone for diabetes-teaching, beyond what his physician has told him. Usual dietary intake: AM: Coffee with half and half Lunch: Out at restaurant—usually Jimmy John’s or fast-food cheeseburger with the works, fries, and soda Dinner: Cooks sometimes at home—this would be grilled chicken or beef, corn or peas, and potatoes or rice with roll and margarine. Soda to drink. Often will meet friends for dinner—likes all foods and especially likes to try different ethnic foods such as Chinese, Mexican, Indian, or Thai. Instructions: This is not a group case study; it is an individual assignment! Complete the following questions using the background information. Remember RD’s are experts in researching evidence-based practice for their patients so you can use other credible sources. ***Be sure to reference your answers and provide a Work Cited page at the end.*** 1. What are the standard diagnostic criteria for T2DM? Which are found in Mitch’s medical record? Blood tests are used to diagnosis diabetes and pre-diabetes because people who have recently developed type 2 may not show any physical symptoms. The three main blood tests are the A1C test, a fasting plasma glucose test (FGP) or and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). For diabetes to be diagnosed the A1C value must be 6.5% or higher, FPG must be 126mg/dL or higher, or OGTT must have a value of 200mg/dL or higher. Another blood test called the random plasma glucose (RPG) test, is sometimes used to check for diabetes during a regular health visit. If the RPG measures 200 micrograms per deciliter or above, and the individual also shows symptoms of diabetes such as increased urination, increased thirst and unexplained weight loss, then a health care provider may diagnose diabetes. Mitch has an HgA1C value of 15.2. 2. Mitch was previously diagnosed with T2DM. His admits that he often does not take his medications. What types of medications are metformin and glyburide? Describe their mechanisms as well as their potential side effects/drug-nutrient interactions. Glyburide belongs to a class of drugs called sulfonylureas, and metformin is in a class of drugs called biguanides. Glyburide lowers blood sugar by causing the pancreas to produce insulin (a natural substance that is needed to break down sugar in the body) and helping the body use insulin efficiently. This medication will only help lower blood sugar in people whose bodies produce insulin naturally. Metformin helps your body control the amount of glucose (sugar) in your blood. It decreases the amount of glucose you absorb from your food and the amount of glucose made by your liver. It also helps your body use its own insulin more effectively • Side effects stomach pain, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness 3. What other medications does Mitch take? List their mechanisms and potential side effects/drug-nutrient interactions. Dyazide mild side effects mild nausea, diarrhea, constipation; • dizziness, headache; • blurred vision; • dry mouth; skin rash. • More serious side effects eye pain, vision problems; • slow, fast, or uneven heartbeat; • feeling like you might pass out; • swelling or rapid weight gain; • urinating less than usual or not at all; headache, trouble concentrating, memory problems, weakness, loss of appetite, feeling unsteady, hallucinations, fainting, seizure, shallow breathing or breathing that stops Drinking alcohol can further lower your blood pressure and may increase certain side effects of hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene. Avoid a diet high in salt. Too much salt will cause your body to retain water and can make this medication less effective. Do not use potassium supplements, salt substitutes, or low-sodium milk while you are taking hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene, unless your doctor has told you to. Lipitor Stop taking atorvastatin and call your doctor at once if you have any of these serious side effects: • • • • unexplained muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness; fever, unusual tiredness, and dark colored urine; swelling, weight gain, urinating less than usual or not at all; or nausea, upper stomach pain, itching, loss of appetite, dark urine, clay-colored stools, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes). Less serious side effects may include: • mild muscle pain; • diarrhea; or mild nausea. Avoid eating foods that are high in fat or cholesterol. Atorvastatin will not be as effective in lowering your cholesterol if you do not follow a cholesterol-lowering diet plan. Avoid drinking alcohol. It can raise triglyceride levels and may increase your risk of liver damage. Grapefruit and grapefruit juice may interact with atorvastatin and lead to potentially dangerous effects 4. Describe the metabolic events that led to Mitch’s symptoms and subsequent admission to the ER with the diagnosis of uncontrolled T2DM with HHS. 5. HHS and DKA are the common metabolic complications associated with diabetes. Discuss each of these clinical emergencies. Describe the information in Mitch’s chart that supports the diagnosis of HHS. Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state is a life-threatening emergency state expressed through elevated blood glucose, hyperosmolarity, and little or sometimes no ketosis. Underlying infections are the most common cause however; other causes include certain medications, non-compliance, undiagnosed diabetes, substance abuse, and coexisting disease. Physical findings of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state include those associated with chronic dehydration. The first step of treatment involves careful monitoring of the patient and laboratory values. Vigorous correction of dehydration with the use of normal saline is critical, requiring an average of 9 L in 48 hours. After urine output has been established, potassium replacement should begin. Once fluid replacement has been initiated, insulin should be given as an initial bolus of 0.15 U per kg intravenously, followed by a drip of 0.1 U per kg per hour until the blood glucose level falls to between 250 and 300 mg per dL. The initiating event in hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state is glucosuric diuresis. Glucosuria impairs the concentrating capacity of the kidney, further exacerbating water loss. Under normal conditions, the kidneys act as a safety valve to eliminate glucose above a certain threshold and prevent further accumulation. However, decreased intravascular volume or underlying renal disease decreases the glomerular filtration rate, causing the glucose level to increase. The loss of more water than sodium leads to hyperosmolarity. Precipitating factors may be divided into six categories: infections, medications, noncompliance, undiagnosed diabetes, substance abuse, and coexisting diseases (Table 2).11–17 Infections are the leading cause of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (57.1 percent)6; the most common infection is pneumonia, often gram negative, followed by urinary tract infection and sepsis.13 Poor compliance with diabetic medications also is thought to be a frequent cause patients with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state typically present with weakness, visual disturbance, or leg cramps.10,21 Nausea and vomiting may occur, but are much less frequent than in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Eventually, patients develop neurologic symptoms of lethargy, confusion, hemiparesis (often misdiagnosed as cerebrovascular accident), seizures, or coma10,13,22 that eventually lead to medical care Physical findings reveal profound dehydration that is manifested by poor tissue turgor10 (which may be difficult to evaluate in older patients)23; dry buccal mucosa membranes; soft, sunken eyeballs; cool extremities; and a rapid, thready pulse.10 A low-grade fever often is present. Initial laboratory findings in patients with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state include marked elevations in blood glucose (greater than 600 mg per dL [33.3 mmol per L]) and serum osmolarity (greater than 320 mOsm per kg of water [normal = 290 ± 5]), with a pH level greater than 7.30 and mild or absent ketonemia. One half of patients will demonstrate a mild anion-gap metabolic acidosis (i.e., 10 to 12). If the anion gap is severe (i.e., greater than 12), the differential diagnosis should include lactic acidosis or other entities not related to hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Vomiting and use of thiazide diuretics may cause a metabolic alkalosis that could mask the severity of acidosis.13 Serum potassium levels may be elevated or normal.13 Creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and hematocrit levels are almost always elevated. The treatment of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state involves a five-pronged approach: (1) vigorous intravenous rehydration, (2) electrolyte replacement, (3) administration of intravenous insulin, (4) diagnosis and management of precipitating and coexisting problems, and (5) prevention. When your cells don't get the glucose they need for energy, your body begins to burn fat for energy, which produces ketones. Ketones are acids that build up in the blood and appear in the urine when your body doesn't have enough insulin. They are a warning sign that your diabetes is out of control or that you are getting sick. High levels of ketones can poison the body. When levels get too high, you can develop DKA. DKA may happen to anyone with diabetes, though it is rare in people with type 2. DKA usually develops slowly. But when vomiting occurs, this life-threatening condition can develop in a few hours. Early symptoms include the following: • Thirst or a very dry mouth • Frequent urination • High blood glucose (blood sugar) levels High levels of ketones in the urine You can detect ketones with a simple urine test using a test strip, similar to a blood testing strip. Many experts advise to check your urine for ketones when your blood glucose is more than 240 mg/dl. When you are ill (when you have a cold or the flu, for example), check for ketones every 4 to 6 hours. And check every 4 to 6 hours when your blood glucose is more than 240 mg/dl. Here are three basic reasons for moderate or large amounts of ketones: • Not enough insulin Maybe you did not inject enough insulin. Or your body could need more insulin than usual because of illness. • Not enough food When you're sick, you often don't feel like eating, sometimes resulting in high ketone levels. High levels may also occur when you miss a meal. Insulin reaction (low blood glucose) If testing shows high ketone levels in the morning, you may have had an insulin reaction while asleep. Ketone testing is usually done: • When the blood sugar is higher than 240 mg/dL • During an illness such as pneumonia, heart attack, or stroke • When nausea or vomiting occur • During pregnancy Other tests for ketoacidosis include: • Amylase blood test • Arterial blood gas • Blood glucose test • Blood pressure measurement Potassium blood test The goal of treatment is to correct the high blood sugar level with insulin. Another goal is to replace fluids lost through urination, loss of appetite, and vomiting if you have these symptoms. 6. HHS is often associated with dehydration. After reading Mitch’s chart, list the data that are consistent with dehydration. What factors in Mitch’s history may have contributed to his dehydration? BUN (blood urea nitrogen -- may be elevated with dehydration) 8-18m- 20 upon admission and 20 the next day BUN:Creatinine 10:1-20:1 Creatinine (may be elevated with dehydration) 0.6 to 1.3 milligrams per deciliter- 1.9 upon admission and 1.3 the next day Sodium (mEq/L) 136–145 131 ! 134 ! 7. Mitch was started on normal saline with potassium as well as an insulin drip. Why are these fluids a component of his rehydration and correction of the HHS? Saline is also used in I.V. therapy, intravenously supplying extra water to rehydrate patients or supplying the daily water and salt needs ("maintenance" needs) of a patient who is unable to take them by mouth. Because infusing a solution of low osmolality can cause problems, intravenous solutions with reduced saline concentrations typically have dextrose (glucose) added to maintain a safe osmolality while providing less sodium chloride. As the molecular weight (MW) of dextrose is greater, this has the same osmolality as normal saline despite having less sodium. The amount of normal saline infused depends largely on the needs of the patient (e.g. ongoing diarrhea or heart failure) but is typically between 1.5 and 3 litres a day for an adult. total body potassium depletion often is unrecognized10 because the level of potassium in the blood may be normal or high.13 The serum potassium level may plummet when insulin is replaced because this forces potassium into the cell. Once urine output is established, potassium replacement should be initiated. Electrolytes should be followed closely (every one to two hours initially) and the patient’s cardiac rhythm should be monitored continuously. If the patient’s serum potassium level is less than 3.3 mEq per L (3.3 mmol per L) initially, insulin should be held and potassium given as two thirds potassium chloride and one third potassium phosphate until the potassium level reaches at least 3.3 mEq per L. If the potassium level is greater than 5.0 mEq per L (5.0 mmol per L), potassium should be held until the level is less than 5.0 mEq per L, but the potassium level should be monitored every two hours. If the initial serum potassium level is between 3.3 and 5.0 mEq per L, 20 to 30 mEq of potassium should be given in each liter of intravenous fluid (two thirds as potassium chloride, one third as potassium phosphate) to maintain the serum potassium level between 4.0 mEq per L (4.0 mmol per L) and 5.0 mEq per L. The critical point regarding insulin management is to remember that adequate fluids must be given first. If insulin is administered before fluids, the water will move intracellularly, causing potential worsening of hypotension, vascular collapse, or death. Insulin should be given as an initial bolus of 0.15 U per kg intravenously, followed by a drip of 0.1 U per kg per hour until the blood glucose level falls to between 250 mg per dL (13.9 mmol per L) and 300 mg per dL. If the glucose level does not decrease by 50 to 70 mg per dL per hour, this rate of administration may be doubled. Once the serum glucose concentration is below 300 mg per dL, dextrose should be added to the intravenous fluid and insulin should be titrated by a low-dose sliding scale until the mental obtundation and hyperosmolarity are resolved. When the patient is able to eat, subcutaneous insulin or the previous treatment regimen may be initiated 8. Describe the insulin therapy that was started for Mitch. What is Lispro? What is glargine? How likely is it that Mitch will need to continue insulin therapy? Explain what ICR means? Insulin lispro is a short-acting, man-made version of human insulin. Insulin lispro works by replacing the insulin that is normally produced by the body and by helping move sugar from the blood into other body tissues where it is used for energy. It also stops the liver from producing more sugar. usually injected within15 minutes before a meal or immediately after a meal. Insulin glargine is a long-acting, man-made version of human insulin. Insulin glargine works by replacing the insulin that is normally produced by the body and by helping move sugar from the blood into other body tissues where it is used for energy. It also stops the liver from producing more sugar. You should use insulin glargine at the same time every day. It comes as a solution (liquid) to inject subcutaneously (under the skin) ICR (insulin to carb ratio) Insulin-to-carbohydrate (I:C) ratios, a guide for determining how much insulin you'll need as a bolus dose to help the body process, or metabolize, the amount of carbohydrate you'll be consuming in a meal or a snack. People with insulin resistance will need more insulin for each CHO serving than people who are more insulin-sensitive. An "average" might be 1 unit of insulin for every 10 or 15 grams of CHO for an adult, or 1 unit for every 20 to 30 grams for a school-age child, depending on the calculation method used. Typically, the daily total of all bolus doses equals about 50 percent of an individual's estimated daily insulin needs, but the amount could range from 40 to 55 percent. A phrase commonly used about diabetes is YMMV ("your mileage may vary"), meaning that what works for one person may not work for another. CHO counting A place to start is at about 45-60 grams of carbohydrate at a meal. 9. Mitch was NPO when admitted to the hospital. Why was this done? What are the signs that will alert the RD and physician that Mitch may be ready to eat? Severe vomiting upon arrival 10. Outline the basic principles for Mitch’s nutrition therapy to assist in control of his DM. 11. Assess Mitch’s weight and BMI. What would be a healthy weight range for Mitch? BMI- 31.6 (obese class 1) Weight- 214 Ideal- 165 would give him a BMI of 24.4 165-170 would be reasonable and a healthy weight range for Mitch 12. Identify and discuss any abnormal laboratory values measured upon his admission (5/12). How did they change after hydration and initial treatment of his HHS (5/13)? Glucose (mg/dL) Osmolality (mmol/kg/H20) Sodium (mEq/L) Potassium (mEq/L) BUN (mg/dL) Creatinine serum (mg/dL) 70–110 285-295 360 ! 136–145 3.5–5.5 8–18 31 ! 0.6–1.2 1510 ! 480 ! 304 ! 131 ! 3.8 ! 134 ! 4.0 20 ! 1.9 1.3 ! 13. Determine Mitch’s energy and protein requirements for weight maintenance. What energy and protein intakes would you recommend to assist with weight loss? Finally, calculate the percent of kcals from protein according to your estimated needs. (remember to provide rationale) Using the Mifflin St Jeor equation I calculated Mitch’s resting energy needs to be 1,755.375 which I then multiplied by an activity factor of 1.3 to get a total of 2,281.987 (1.4 to get a total of 2,457.525) Since the goal for Mitch is weight loss I then subtracted 500 calories which would put him on track for losing 1 pound per week through his diet alone. As exercise increases these requirements will change as well. Protein needs= 0.8-1.0 g/kg/d 14. Using a computer dietary analysis program or food composition table, calculate the kcalories, protein, fat, CHO, fiber, cholesterol, and Na content of Mitch’s diet. Fill-in the blanks. Kcal = 1685.16 compared to kcal needs of 2281.987/ 2457.525 (73%/ 68% of needs) Protein = 87.8g and 26.05% kcal; compared to protein needs of ___________g (15-25% of needs) Fat = 49.09g and 31.56% kcal; compared to fat needs of 30-35% kcal Saturated fat = 14.52g and 7.75% kcal; compared to SFA needs of <7% kcal CHO = 223.04g and 52.9% kcal; compared to CHO needs of 45-50% kcal What about consistency of CHO at mealtimes? fiber = 8.13g; compared to fiber needs of 25-30g (30.11% of needs) chol = 217.94mg; compared to cholesterol needs of <200mg (108.97% of needs) Na = 1994.95mg; compared to Na needs of <2300mg (86.73% of needs) 15. Prioritize two nutrition problems and complete the PES statement for each. 16. Determine Mitch’s Nutrition Prescription using his diet history as well as your assessment of his energy requirements. 17. Outline the steps you would use to teach Mitch about nutrition and diabetes during an initial 15 minute nutrition education session at bedside. (Hint: what are key concepts you want him to leave with that will help him in the week or two before he sees an outpatient RD/CDE). 18. What would you monitor at a 3-day follow-up in the hospital? What would you monitor at a 3 month follow-up at an out-patient diabetes clinic? 19. Write an ADIME note for your initial nutrition assessment.