financial instruments usage and strategic earnings reporting

advertisement

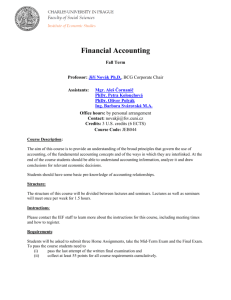

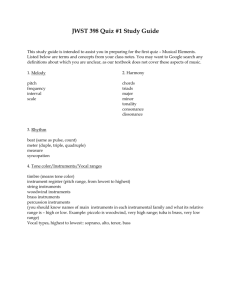

FINANCIAL INSTRUMENTS USAGE AND STRATEGIC EARNINGS REPORTING – THE COMPLEMENT HYPOTHESIS EXAMINATION Hung-Shu Fan, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan acct1008@mails.fju.edu.tw, *corresponding author Ching-Lung Chen, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan clchen@yuntech.edu.tw Chia-Ying Ma, Soochow University, Taiwan cyma@scu.edu.tw Yan-Ting Lin, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan 067670@mail.fju.edu.tw ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to examine whether listed firms in Taiwan use discretionary accruals and financial instruments regulated under Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No.34 as complement tools in reporting earnings. We estimate a set of simultaneous equations that captures managers' incentives to enhance earnings performance through financial instruments usage and accrual management. The empirical results of two-stage least squares regressions reveal that, as conjectured, the financial instruments usage is positive associated with the magnitude of discretionary accruals and support the complement hypothesis. It suggests that managers jointly use financial instruments and discretionary accruals to increase earnings and, besides the risk hedging purpose, provides alternative explanation for the multi-goals of financial instruments usage. These results remain robust to various specification tests. Keywords: Complement hypothesis, Discretionary accruals, Earnings management, Financial instruments usage, INTRODUCTION The participants in financial derivatives market include hedgers, speculators and arbitrageurs. Hedgers use financial instruments to lock-in prices in order to avoid exposure to adverse movements in the price of an asset. Speculators take short-term positions in the market and consider derivatives as instruments of profit making, instead of as risk hedging tools. The arbitrageurs enter simultaneously into contracts in two or more markets to lock-in riskless profit by exploiting price differentials or imbalances. Nonetheless, how financial instruments are actually used by non-financial firms is still largely unknown in the literatures. Although firms can use financial instruments to speculate and/or to arbitrage on private information, extant empirical studies highlight the risk hedging motive and ignore the important roles of the other two participants. The purpose of this study is to examine the possible complement relationship between the financial instruments usage and aggressive discretionary accruals in enhancing earnings (hereafter, the complement hypothesis) for listed firms who recognized the usage of financial instruments regulated under Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No.34 (Financial Accounting Standards Board 2004) in Taiwan. Before the enactment of SFAS No.34, firms only disclosed some of the financial instruments information in the footnotes and these disclosures were not uniform. Therefore, there was a lack of visibility or transparency for financial instruments usage. Because SFAS No. 34 requires firms to recognize all financial instruments as assets or liabilities in the balance sheet and also requires them to adopt mark to market approach to recognize the resulting gains or losses from the changes of financial instruments’ fair value at the end of fiscal year in their income statements. Thus, the magnitude of financial instruments usage to some extent would have an effect on listed firms’ reported earnings. Rather, the active usage of financial instruments is thought to add value by alleviating a variety of market imperfections through hedging (Adam & Fernando, 2006). Recently, Gèczy et al. (2007) suggest that financial derivatives involve real action which plays an important role in strategically boosting firm’s earnings and view speculation as a positive profitability activity. Inspired by the study of Gèczy et al. (2007), the present study is motivated to examine whether listed firms jointly use financial instruments and discretionary accruals to manipulate their earnings. Since earnings have two components, cash flows from real operations and accruals, the earnings reporting choices can result from cash flows and/or accruals. Facing increasing pressure to meet benchmark earnings, managers have incentives to use both discretionary accounting choices and real operation activities, such as using financial instruments, to manipulate earnings. In other words, except using the discretionary accrual, managers also can manipulate earnings through purchase and/or sell financial instruments. Recently, Gèczy et al. (2007) suggest that financial derivatives can be used to hedge market risk exposures or to speculate on movements in the value of the underlying asset. The authors argue that the speculation hypothesis generally implies that the derivative transactions are undertaken with the primary intention of making a profit. Adam & Fernando (2006) also document that gold mining firms have consistently realized economically significant cash flow gains from their derivatives transactions. Thus, if managers rather use financial instruments to increase earnings (and/or cash flow) but to smooth earnings, the substitution relationship between financial instruments usage and discretionary accruals is called for further examinations. Recent studies document that managers’ market views influence their attempting to time commodity markets with derivatives usage decisions (Stulz, 1996; Faulkender, 2005; Brown et al., 2006; Adam & Fernando, 2006). Stulz (1996) calls this practice “selective hedging”. He claims that selective hedging will increase shareholder value if managers have an informational advantage relative to other market participants. Thus, it is possible that managers believe that they can create shareholder value by incorporating speculative elements into their financial instruments usage decisions. Hitherto, many studies view discretionary accruals as the primary tools to manipulate earnings. However, managers also can increase earnings by using financial instruments that boost their firms’ cash flows. Once managers believe they have a comparative information advantage relative to the market and, hence, to view speculation as a positive profitability activity, the magnitude of financial instruments usage will be enlarged. In such case, financial instruments usage will play an important role in strategically boosting firm’s earnings. It is expected that both the financial instruments usage and aggressive discretionary accruals play important roles in elucidating firms’ income-increase reporting behaviors. Inspired by the studies of Adam & Fernando (2006), Gèczy et al. (2007) and among others which view speculation as a positive profitability activity, the present study examine the possible complement relationship between the financial instruments usage and aggressive discretionary accruals in enhancing earnings for listed firms with active financial instruments usage under SFAS No.34 in Taiwan. The empirical results of the two-stage least squares regression indicate that, as conjectured, financial instruments usage is positive association with the magnitude of discretionary accruals and supports the complement hypothesis. It suggests that managers use financial instruments and discretionary accruals jointly to increase earnings, which is inconsistent with the studies of Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005). Reporting requirements on financial instruments usage may potentially affect firms’ behavior with respect to production and risk management, and thus the derivative instruments usage. Sapra (2002) demonstrates that it is possible for mandatory financial instruments disclosures to result in excessive speculation in the financial instruments market. Our empirical results to some extent evidence the possible potential multi-purposes of financial instruments usage and support the findings of Sapra (2002). These results remain robust to various specification tests. Overall, the present study documents that financial instrument has cash flows effect, then influence reporting earnings, and provides feedback for regulators with respect to the subsequent reporting requirement in capital market. The present study enriches the financial instruments related research from two angles. First, although Barton (2001) finds that derivatives serve as a partial substitute role to discretionary accruals subject to managers’ income smoothing assumption, the potential cash flows effect of financial instruments can be a potentially important motive for firms to use financial instruments. We examine whether financial instruments usage is a complement tool for discretionary accruals to manipulate earnings. The second angle, this study contributes to the literature by examining, besides the prevailing hedging risk hypothesis, financial instruments can be used to speculate on movements in the value of the underlying asset. If managers can boost earnings by using multiple tools, i.e., financial instruments and aggressive discretionary accruals, the question naturally arises regarding how managers combine these instruments to gain benefits. This examination, to some extent, provides evidence to understand the substitute or complement nature of financial instruments usage strategy in earnings increase and assists regulators to evaluate the possible policy effect of SFAS No. 34 in Taiwan. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the related prior studies and develops the empirical hypothesis. Section 3 presents the empirical design. Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the robustness test and Section 6 concludes the study. BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEWS Accounting for Financial Instruments in Taiwan The ongoing growth in the use of financial instruments accompanying with the financial instruments abuses have motivated accounting regulators to develop and stretch financial instrument-related disclosure requirements in Taiwan. First, The Financial Accounting Standards Committee of the Accounting Research and Development Foundation in Taiwan issued SFAS No.14 regulating the accounting treatments of Foreign Currency Translation transactions in December 1998. Subsequently, SFAS No.27 (Disclosure of Financial Instruments) was issued in 1997 and aimed to improve the transparency of listed firms’ financial instruments usage. Namely, it required the disclosure of the extent (i.e., the contractual or notional amount), nature, terms, and the concentrations of credit risk for all financial instruments. Since the requirements of disclosing of financial instruments were not clear and uniform, the disclosures about financial instruments in financial statement are obscure and discretionary. SFAS No.34, Accounting for Financial Instruments, was issued in December 2004 and was effective for fiscal years beginning after 2006. This new standard requires all financial instruments owned by the listed companies to be initially recognized in the balance sheet as either liabilities or assets at their fair values. It also requires them to adopt mark to market approach to recognize the resulting gains or losses from financial instruments’ fair value changes at the end of fiscal year in their income statements or in equity section of the balance sheet, depending on the intentions of financial instruments usage and the types of hedging. This standard setting provides the present study with a unique opportunity to identify a distinct financial instruments users sample that recognized financial instruments in their annual reports during 2006~2007 to examine the alternative motivation of financial instruments usage, besides the risk hedging motivation. Related Research Firms normally make plans based on expectations of what foreign exchange rates, interest rate, and commodity prices will be over the near time. If prices or rates change, the result of operations and cash flows will also differ from expectations. When firms have incentives to reduce the volatility of cash component of earnings through real risk-management activities, one possible way is to use derivatives to hedge the risks inherent in commodity prices, foreign currencies, and interest rate (Nance et al., 1993; Tufano, 1996; Gèczy et al., 1997). That is, firms can use properly structured hedging derivative forms, whose rate or price moves in the opposite direction of the rate or price of the underlying item being hedged, to reduce the magnitude of differences. Breeden & Viswanathan (1998) find that hedging reduces noise related to exogenous factors and hence decreases the level of asymmetric information regarding a firm’s earnings and its quality. This finding again is supported by the study of Dadalt et al. (2002). There are substantial studies examining the using of derivatives to smooth earnings/cash flows volatilities. For examples, Smith & Stulz (1985) show that the use of derivatives to hedge can maximize shareholder value because hedging may be reduce expected tax and expected costs of financial capital by reducing the probability that the firm encounters financial distress. In advance, there are rich bodies of studies exploring the various channels through which financial derivatives hedging can contribute to increase firm value (e.g., Froot et al., 1993; DeMarzo & Duffie, 1995; Allayannis & Ofek, 2001; Graham & Rogers, 2002). It seems the usage of financial derivatives is associated not only with smoothing earnings but also with enhancing firm’s value. Another line of research examines the tradeoffs managers make between derivatives and other risk management tools. For example, Schrand & Unal (1998) document that managers of thrift institutions integrate derivatives and the composition of loan portfolios to manage overall risk. Petersen & Thiagarjan (2000) using gold mining companies and Pincus & Rajgopal (2002) using oil & gas firms as sample examine the interaction of accounting choice and derivatives hedging and evidence similar tradeoffs pattern. Barton (2001) uses sample firms of Fortune 500 non-financial companies and estimates a set of simultaneous equations that captures managers’ incentives to maintain a desired level of earnings volatility through hedging and accrual management. The author concludes that managers use derivatives and discretionary accruals as partial substitutes for smoothing earnings. Following Barton (2001), Wang & Kao (2005) based on Taiwanese listed companies sample also find the substitution relationship between discretionary accruals and derivatives in earnings smoothing. However, the finding of Wang & Kao (2005) is based on SFAS No.27 (Disclosure of Financial Instruments) and on relative small hand-collected sample size (109 sample firms with 327 firm-year observations). Their underlying premise is also based on the comparative cost and benefit of discretionary accruals and derivatives as Barton’ (2001) U.S. capital market setting. Recently, Kim et al. (2006) examine whether operational hedging (firms reporting foreign sales) can be viewed as either a substitute or a complement role to financial derivatives hedging when a firm intends to reduce the volatility of future cash flows and, thus, to possibly increase firm value. The authors find that non-operationally hedged firms use more financial hedging relative to their level of foreign currency exposure and suggest operational hedging is complement to financial derivatives hedging. According to above, to some extent, managers have incentives to smooth and/or enhance earnings and financial instruments can be an effective tool to meet their earnings management goals. Hypothesis Developments Prior studies document that financial instruments can be treated as a mean to strategically manipulate firm’s earnings. Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005) propose the income smoothing hypothesis and suggest both derivatives and discretionary accruals can be used for reducing earnings volatility. Recently, Adam & Fernando (2006) suggest that the active usage of derivatives is thought to create firm value by alleviating a variety of market imperfections through hedging. Gèczy et al. (2007) also point out that derivatives can be undertaken with the intention of making a profit. Based on the above arguments, financial instruments usage can be viewed as either a substitute or a complement tool to a firm’s discretionary accruals when it intends to reduce a firm’s volatility of future cash flows or to possibly increase a firm’s earnings. In the income smoothing hypothesis, it is expected that financial instruments usage can be partially substituted by the use of discretionary accruals. As for the earnings increasing hypothesis, it is expected that financial instruments usage is a complement tool to the use of discretionary accruals. Thus, that the goal of strategically uses of financial instruments is earnings smoothing or earnings increasing, to some extent, is an empirical issue in differential capital market setting. Although Ewert & Wagenhofer (2005) develop an analytical model and demonstrate that real activities manipulation increases when tightening accounting standards make accruals management more difficult. However, accruals management and real activities manipulation (e.g., financial instruments usage) are not mutually exclusive strategies for managers and multiple tools can achieve the same earnings objective. Firms can use both accruals management and real activities manipulation to boost or constrain earnings and obtain the greatest effect through a coordinated approach (Mizik & Jacobson 2007, 2008). In other words, both accruals management and financial instruments manipulation play important roles in concurrently strategically boosting and/or suppressing firm’s earnings. As for the relative cost determination of alternative earnings management tools, prior studies show that the reporting and/or litigation costs in U.S. are relatively higher than that in other developed economies (e.g., Antle et al., 1997). The higher reporting and/or litigation costs bring about the cost-benefit consideration of accruals management and financial instruments usage manipulation an important issue in managers’ strategic earnings reporting decisions. However, the relative cost-benefit of accruals management and financial instruments usage manipulation bonded by the lower reporting and/or litigation costs may make the earnings management incentives effect dominate the relative cost-benefit effect, and then, weaken the effect of cost determination in the selection decisions of alternative earnings management tools. Yet, the institutional consideration for managers to incorporate the relative cost-benefit of alternative manipulating tools into strategic earnings reporting decisions are likely to be less in Taiwan, where reporting and litigation costs are relatively lower.1 Thus, without higher reporting and litigation costs to trigger the relative cost-benefit advantage consideration between accruals management and financial instruments usage manipulation, we expect the earnings management incentives effect will dominate the relative cost-benefit effect in managers’ accruals management and financial instruments usage manipulation decisions. Stulz (1996) documents that managers’ market views influence their attempting to time commodity markets with financial derivatives usage decisions. The author claims that selective hedging will increase shareholder value if managers have an informational advantage relative to other market participants. Thus, it is possible that managers believe that they can create shareholder value by incorporating speculative elements into their financial instruments decisions. Sapra (2002) suggests that greater transparency about a firm's derivative activities is not necessarily a panacea for imprudent risk management strategies. The author shows that transparency actually induces the firm to take excessive speculative positions in the derivative market. In other words, after SFAS No.34 is enforced in Taiwan, once managers believe they have a comparative information advantage relative to the market and, hence, view speculation as a positive profitability activity, the magnitude of financial instruments usage will enlarge. In such situation, besides the aggressive discretionary accruals, financial instruments usage, involving real actions which have cash flows effects, play an important role in strategically boosting firm’s earnings. It is expected that both the financial instruments usage and aggressive discretionary accruals play important roles in elucidating firms’ income-increase reporting behaviors. Inspired by the studies of 1 Taiwan is characterized as a smaller stock markets, weaker investor protections, and lower disclosure requirements (Chin et al., 2009). Chin et al. (2007) and Duh et al. (2009) also documented that the auditor litigation costs in Taiwan are lower than those in other developed economies. Thus, both the lower disclosure requirements and auditor litigation costs form a somewhat relative weaker financial reporting costs environment. Sapra (2002), Adam & Fernando (2006), Gèczy et al. (2007) that view financial instruments usage as positive profitability activities, the present study conjectures that firms with active financial instruments positions will simultaneously use discretionary accruals to boost their earnings. Namely, this study examines the complement relationship between the financial instruments usage and aggressive accruals management in enhancing earnings. From the above discussions, we therefore establish our hypothesis as follows: H1: The financial instruments usage regulated by SFAS No.34 is positive association with the magnitude of discretionary accruals. RESEARCH DESIGN Data and Sample Selection Years 2006 and 2007 are chosen as the observation years because SFAS No.34 was enforced on 2006 and later annual reports in Taiwan. The sample firms used in this study are composed of publicly traded companies listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (hereafter, TSE) and Gre Tai Securities Market (hereafter, OTC) in Taiwan. That only TSE-listed and OTC-listed firms are considered is due to the feasibility of collecting the necessary reliable data. The empirical data are retrieved from both the Taiwan Economic Journal Database (TEJ) and the Open Market Observation Post System (MOPS) of the TSE and OTC in Taiwan. Because there are insufficient sample firms in some industries for estimating discretionary accruals, except food (code 12), textile (code 14) electronic (codes 23, 24, 30) industries, we follow the study of Chang et al. (2003) and group some resembling industries into one integrated industry to obtain larger firm sample and avoid the inefficiency problem of regression coefficients estimation. Electric machinery (code 15) and electric wire (code 16) are combined as “electric” industry; plastics (code 13), chemical (code 17), and rubbery (code 21) are combined as “plastic and chemical” industry; cement (code 11), iron (code 20), and construction (code 25) are combined as “construction and building materials” industry; tourism (code 27) and general merchandise (code 29) are combined as “service and sales” industry. Table 1 reports the resulted seven industries in the study. Table 2 presents the sample selection process of the present study. Consistent with extant literature, finance-related institutions (codes 2801 to 2888) are excluded as they are subject to different disclosure requirements and regulations that make using industry cross-sectional Jones model to estimate discretionary accruals problematic. The total observations of firms traded in TSE and OTC during 2006~2007 are 2,459 firm/years. The present study follows the study of Chang et al. (2003) and deletes glass-ceramic, paper, automobile industries, shipping and transport industry, oil industry, and other industries because of too few listed firms causing trouble in estimating discretionary accruals. We also deleted 394 observations for data deficient or unavailable. These selection procedures yield a final sample of 1,834 firm/years, which include 837 firms in year 2006 and 997 firms in year 2007, respectively. Table 1: Integrated Industry Analysis. Integrated or Individual Industry Industry Composition Construction and Building Materials Construction, Steel, and Building (11,20,25) Plastic and Chemical (13,17,21) Plastic, Chemical, Rubber and Tire Electric (15,16) Electric Machinery, Electric Wire and Cable Service and Sales (27,29) Tourism and General Merchandise Electronic (23, 24, 30) Electronic Foods (12) Foods Textile (14) Textile and Fiber Table 2: Sample Selection. Firms listed on TSE and OTC during 2006~2007 Less: Too few listed firms industry: Shipping and Transport industry Oil industry Paper industry Glass and Ceramic industry Automobile industry Other industries Firms’ data unavailability: Final samples 2006 1,229 2007 1,230 Total 2,459 (22) (12) (7) (7) (5) (64) (275) 837 (22) (12) (7) (5) (5) (63) (119) 997 (44) (24) (14) (12) (10) (127) (394) 1,834 Variables Measurement and Empirical Model This section presents the methodology implementing to examine the hypothesis. Since the usage of financial instruments regulated by SFAS No.34 and discretionary accruals may be endogenous, the simultaneous equations are developed to avoid bias and the inconsistent coefficients estimation of ordinary least squares (OLS). Following Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005), the relationship between financial instruments usage and discretionary accruals is tested by the following simultaneous equations estimated by two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression. To test our hypothesis, the present study uses the following simultaneous equations: | DIC |it 0 1DER it 2COMPit 3STOCK it 4 DEBTit 5 RDit 6FS it 7 IDR it 8INDit 9 DPR it 10FLEX it 11 | OCF |it 12ROA it 13SIZE it 14MILLS it it and ................................................................(1) DER it 0 1 | DIC |it 2COMPit 3STOCK it 4 DEBTit 5 RDit 6FS it 7 IDR it 8INDit 9QR it 10CYCLE it 11DIV _ YIELD it 12ST _ DEBTit 13MILLS it it ......................................................(2) where: | DIC | and DER are the proxies for discretionary accruals and financial instruments usage regulated by SFAS No.34, respectively. In simultaneous equations, | DIC | and DER are endogenous variables, concurrently, the other variables are control variables and will be defined in section 3.3. Furthermore, the possible self-selection problem is corrected by adding the inverse Mills ratio (MILLS) variable, which suggested by Heckman (1979), into the simultaneous equations. Because the sample firms do not have sufficient time series data to estimate the parameters of the Jones (1991) model when determining | DIC | , we measure discretionary accruals (DA) via the cross-sectional version of the Jones (1991) model as reported in DeFond & Jiambalvo (1994)2 . Subramanyam (1996) and Bartov et al. (2001) indicate that this approach is generally better specified than the time-series model. Recently, Kothari et al. (2005) suggest that incorporating a performance measure into Jones model to estimate the parameters of the nondiscretionary accruals can effectively enhance the model specification. Therefore, we estimate the discretionary accruals (DA) by the prediction errors from the cross-sectional Jones model of Kothari et al. (2005). As discussed above, we follow the study of Chang et al. (2003), grouping some resembling industries into one integrated industry to come up with a larger sample, thus to avoid the inefficiency of regression coefficients estimation when getting the estimates of nondiscretionary accruals. The financial instruments regulated by SFAS No.34 include: financial assets/liabilities at fair value through profit or loss, held-to-maturity investments, available-for-sale financial assets, hedging derivative assets/liabilities, financial assets/liabilities carried at amortized cost, financial assets carried at cost. Thus, in order to catch the earnings management intention of the financial instruments usage, our second pivotal variable DER is measured as the change in sum of notional amount of financial assets and financial liabilities regulated by SFAS No.34 scaled by lagged total assets. It is described as follows: DER TFA it TFA it 1 / Ait 1 where: TFA is defined as the sum of notional amount of total financial assets plus total financial liabilities regulated by SFAS No.34. According to the definition, the DER may be positive or negative. Positive DER indicates that there is an increasing usage of financial instruments regulated by SFAS No.34. On the other coin, negative DER reveals that there is a decreasing usage of financial instruments regulated by SFAS No.34. 2 The modified Jones model proposed by Dechow et al. (1995) is also used to enhance the robustness of our study. The result is discussed in the robustness check. Definitions of Control Variables Inverse Mills Ratios To measure the inverse Mills ratio, we first estimate the following equation to explain the decision to use financial instruments: USERit 0 1COMPit 2 STOCK it 3 DEBTit 4 RDit 5 FSit 6 IDRit 7 INDit 8QRit 9CYCLEit 10 DIV _ YIELDit 11ST _ DEBTit it ....(3) where: USER is a binary variable and coded 1 if the firm uses financial instruments, 0 otherwise. We use probit regression on the full sample of 1,834 firm-years to estimate equation (3). Following Greene (2004), and W are denoted as the coefficient vector and the explanatory variable vector in the financial instruments user model respectively. And let be the estimate of . Then, the inverse Mills ratio is defined as: MILLS ( W) / ( W) if USER variable equals 1 and MILLS ( W) /[( W) 1] if USER variable equals 0, where: () and () are denoted as the standard normal probability density function and the standard normal cumulative distribution function, respectively. We include MILLS as an additional control variable to correct for potential self-selection bias in the empirical equation. Common Explanatory Variables for both | DIC | and DER Equations Cash compensations for managers are increased with the firm’s performance such as profit. The interest conflicts exist between managers and shareholders conditional on maximizing managers’ self-interests. Managers might want to increase their cash compensations by increasing earnings myopically. It is expected that cash compensations (COMP) will be positively associated with the pivotal variables, i.e., | DIC | and DER . COMP is measured as the directors’, supervisors’, and CEOs’ salaries and bonuses, scaled by lagged total assets. It is also found that managers have incentives to increase earnings to raise their values brought from ownership. Thus, we expect managers’ stock holdings to be associated with | DIC | and DER . Stock holdings (STOCK) are measured as the sum of percentages of the stock ownerships owned by directors, supervisors, and CEO. In addition, managers may avoid violating the debt covenants based on accounting performance. DeFond & Jiambalvo (1994) provide evidence that managers tend to increase earnings when the leverage is raised. We use debt-to-assets ratio (DEBT), defined as total liabilities divided by total assets, to proxy for leverage risk. It is expected that DEBT will be associated with our two pivotal variables, i.e., | DIC | and DER . Baber et al. (1991) point out when pre-R&D earnings are low, managers may strategically prune away investment in R&D expenditures. It suggests that R&D intensity will be positively associated with | DIC | and DER . Thus, we incorporate R&D intensity into empirical models to capture the relationship between R&D intensity and two explained variables. R&D intensity is defined as the ratio of R&D expense to equity market value. Moreover, Jorion (1990) documents that foreign sale is positively associated with the absolute value of exposure to foreign exchange rate risk. Since exports sale is an important revenue for listed firms in Taiwan, we expect firms with international diversification have more opportunity to manage earnings by way of | DIC | and DER . We thus use ratio of foreign sales to total sales (FS) to measure firms’ business diversification to capture the possible influences of diversification on | DIC | and DER . Wang & Kao (2005) reveal that interest-rate risk is positive associated with | DIC | and DER . Following Wang & Kao (2005), we use the absolute value of the difference between interest revenues and interest expenses scaled by net sales (IDR) to measure interest-rate risk and expect IDR will be positive with | DIC | and DER . Naturally, the percentage of firms belonging to electronic industries is 64.89% in our empirical data, thus, an electronic industry dummy variable (IND) is used to control for the industry characteristics. IND is coded 1 if the sample firm belongs to electronic industry and 0 otherwise. Control Variables for the Discretionary Accruals Model Previous studies document that when pre-management earnings are low, managers might myopically increase earnings to maintain the common dividend payout levels. Dividend payout ratio (DPR) is defined as the ratio of cash dividends to earnings per share before discretionary accruals. In addition, managers in industries with more accounting flexibility are likely to manage accruals to a greater extent (Barton, 2001). The present study follows Barton (2001) and uses the root mean squared error of equation (4) as a proxy for industry accounting flexibility (FLEX). It is expected that FLEX will be positively associated with the magnitude of discretionary accruals. The literature related to discretionary accruals are based on the maintained hypothesis; however, Dechow et al. (1995) point out that the modified Jones model will overstate the magnitude of discretionary accruals for firms with extreme operating cash flows. The absolute value of operating cash flows scaled by lagged total assets (|OCF|) is used to control for the potentially measurement error. If ROA of a firm is high, the manager is less likely to myopically increase earnings (Bowen et al., 1995). ROA in this paper is measured as the ratio of net income before interest and depreciation net of tax to average total assets. The relation between ROA and | DIC | is predicted to be negative. In the view of economics of regulation, large firms tend to manage earnings to avoid the monitors from capital market regulator and the government. DeFond & Park (1997) provides evidence on the positive relation between firm size and the magnitude of discretionary accruals. The natural logarithm of net sales, denoted as SIZE, is the proxy of firm size in this paper. Control Variables to Financial Instruments Usage Regulated by SFAS No.34 Firms with large current assets face less financial distress (Nance et al. 1993). Froot et al. (1993) also indicate that the liquidation of assets is negatively associated with the use of derivatives. Therefore, quick ratio (QR), defined as the ratio of quick assets to current liabilities, is used to be a proxy for a firm’s liquidation. Firms with long cash conversion cycles are more likely to benefit from hedging because their cash flows are exposed to volatility in market prices (Barton 2001). Cash cycle (CYCLE) is measured as the average collection days of accounts receivables, net of the average payment days of accounts payables, plus average days of inventory sell-out. CYCLE variable is predicted to be positively related with DER . In addition, Barton (2001) documents that large expected dividend yield increases the firm’s cash need, managers tend to hedge against the volatility in cash flows. Hence, we expect that dividend yield (DIV_YIELD), measured as the ratio of cash dividends to market value of common stocks, will be positively correlated with DER . Finally, firms with shorter debt maturity are more likely to use interest rate swaps to hedge risk exposure, thus, a positive correlation between short maturity debts and DER is expected (Barton 2001). Short maturity debts (ST_DEBT) are measured as current liabilities divided by total liabilities. EMPIRICAL RESULTS We first present the summary statistics and correlation analyses of related variables in this study. Second, two-stage least squares regression results for the DER and |DIC| simultaneous equations are presented. Descriptive Statistics Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics for the related variables in this study. The average absolute discretionary accruals (|DIC|) is 0.073, which is statistically significant at 1% level. The average financial instruments usage (DER) is 0.019. The average ratio of cash compensations (COMP) is 0.9%. It indicates that managers receive relative moderate cash compensations in the sample. The average ownership of managers (STOCK) is 23.8% (median is 20.9%) and show the ownership structures of firms in Taiwan are characterized by a higher degree of concentration. The average ratio of leverage and average R&D intensity are approximately 0.37 and 0.024, respectively. More than half of revenues come from foreign sales documents that international business activities play an important role in the revenues structure in our sample. The average ratio of interest difference is 0.014. The mean of FLEX is 0.017 and documents that there is little difference in the flexibility of GAAP in different industries. The average ROA of the sample is approximate 6%. The average cash conversion cycle is about 101 days. The average dividend yield is 3%. Finally, the average SH_DEBT is 0.758 which reveals half of the total liabilities are short maturity debts in the sample of this study. Table 3: Descriptive Statistics of Related Variables (n=1,834). Standard First Variables Mean Median Deviation Quartile |DIC| 0.073 0.094 0.023 0.049 DER 0.019 0.092 -0.005 0.000 COMP 0.009 0.008 0.003 0.007 STOCK 0.238 0.135 0.139 0.209 DEBT 0.371 0.175 0.236 0.364 RD 0.024 0.035 0.003 0.013 FS 0.530 0.441 0.164 0.571 IDR 0.014 0.086 0.002 0.005 IND 0.650 0.477 0.000 1.000 DPR 0.399 0.420 0.000 0.410 FLEX 0.017 0.008 0.017 0.017 |OCF| 0.108 0.110 0.039 0.080 ROA 0.059 0.103 0.017 0.064 SIZE 14.819 1.496 13.868 14.682 QR 1.824 2.142 0.822 1.261 CYCLE 101.101 135.138 45.063 79.659 DIV_YIELD 0.030 0.028 0.000 0.025 Third Quartile 0.093 0.020 0.012 0.303 0.486 0.031 0.822 0.010 1.000 0.663 0.020 0.152 0.115 15.645 2.083 122.678 0.051 ST_DEBT 0.754 0.210 0.619 0.801 0.934 Legends: |DIC|=discretionary accruals. DER=financial instruments usage regulated by SFAS No.34. COMP=cash compensations for managers scaled by lagged total assets. STOCK=the ownership owned by managers. DEBT=the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. RD=the ratio of R&D expenditures to market value of common equity. FS=the ratio of net foreign sales to net sales. IDR=the absolute value of difference between interest revenues and interest expenses scaled by net sales. IND=1 if the sample firm belongs to electronic industry, and 0 otherwise. DPR=the ratio of cash dividends to earnings net of discretionary accruals per share. FLEX=the root mean squared error of equation (4). |OCF|=the absolute value of operating cash flows scaled by lagged assets. ROA=the ratio of net income before interest and depreciation net of tax to average total assets. SIZE=nature log of net sales. QR=the ratio of quick assets to current liabilities. CYCLE=the average collection days of accounts receivables, net of the payment days of accounts payables, plus average days of inventory sell-out. DIV_YIELD=the ratio of cash dividends for common stock to market value of common equity. ST_DEBT=current liabilities scaled by total liabilities. Correlation Analysis According to the study of Barton (2001), earnings is the sum of cash flows and accruals, thus, 2 2 the variance of earnings ( E ) is a function of the variance of cash flows ( C ), the variance of accruals ( A ), and the correlation coefficient of cash flows and accruals ( CA ). In other 2 words, the equation E C A 2CA C A will be hold. Therefore, it is reasonable to observe that managers smooth earnings volatility by adjusting cash flows volatility, accruals volatility, and/or the correlation between cash flows and accruals. However, when the myopic earnings increase motivation replaces the possible earnings smoothing behavior by managers, it is expected to find distinct relationship between financial instruments usage and discretionary accruals, which is different with those observed in Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005). The present study first follows the procedure suggested by Barton (2001) and correlates the earnings volatility with | DIC | and DER variables to provide preliminary comparison evidences. We use sample firm’s quarterly data to calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) to measure volatility. Panel A in Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the coefficient of variation for earnings, operating cash flow, and total accruals. The average coefficients of variation of earnings, operating cash flow, and total accruals are 2.660, 4.926, and 8.948, respectively. It is found that total accruals are more volatile than operating cash flows and earnings. 2 2 2 Panel B in Table 4 presents the correlations between DER ( | DIC | ) and the coefficient of variation (CV) of related variables. It documents that DER is insignificantly negative-associated with the volatilities of cash flows and accruals. But the rank correlations between DER and the volatilities of earnings is 0.058 which is statistically significant at 5% level. This result is inconsistent with the finding of Barton (2001) and does not support the DER smoothing earnings volatility conjectures. The correlation between | DIC | and volatilities of earnings is 0.005 which is positive but not statistically significant. Operating cash flows and total accruals are both negatively associated with | DIC | and again are inconsistent with the finding of Barton (2001). Overall, the fact that financial instruments usage regulated by SFAS No.34 (i.e., DER) and discretionary accruals (i.e., |DIC|) are positively associated with the volatility of earnings suggests that managers do not use both financial instruments and discretionary accruals to smooth earnings volatility. Thus, the conclusion that the usage of financial instruments can smooth earnings volatility, which is suggested by Barton (2001), is called for further examinations. Although the untabulated Pearson/Spearman correlation matrix for the related variables in equations reveal most of the independent variables are correlated with others, the variance inflation factors (VIF) of the explanatory variables (unreported) in the regressions are less than 10 and do not suggest severe multi-collinearity problems (Neter et al., 1989). Table 4: Rank Correlations between |DIC| and DER and the Coefficient of Variation. Panel A. Descriptive Statistics for the Coefficient of Variation(n=1,834) Standard First Third Variables Mean Median deviation quartile quartile Coefficient of variation for the variable: a Earnings 2.660 18.774 0.305 0.570 1.196 Operating cash flows 4.926 23.029 0.803 1.704 3.704 Total accruals 8.948 46.213 1.239 2.431 5.375 Correlation between operating cash -0.857 0.292 -0.993 -0.970 -0.875 flows and total accruals Panel B. Correlations between |DIC|, DER and the Coefficient of Variation (n=1,834) b CV of variables |DIC| DER CV of earnings 0.005 0.058** CV of operating cash flows -0.025 -0.002 CV of total accruals -0.053** -0.005 Correlation between operating cash -0.031 -0.007 flows and total accruals Legend: a. The coefficient of variation is the standard deviation of the variable divided by the absolute value of its mean, based on quarterly data for 2006 and 2007. b. *, **, *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively, based on two-tailed tests. Simultaneous Regression Results From Table 5, the coefficients of DER in Equation (1) and |DIC| in Equation (2) are 3.067 (t=29.28) and 0.256 (t=7.00), respectively, and both positively statistically significant at 1% level. It documents that managers use both financial instruments and discretionary accruals to increase earnings, yet, not to smooth earnings. It is reasonable to conclude that managers use financial instruments and discretionary accruals as complement tools rather than substitute tools in create firms’ net income. Our hypothesis is empirically supported. The empirical results from common control variables are discussed as follows. The coefficients of COMP variable are -0.501(t=-2.43) and -0.193 (t=-0.67) in the DER and |DIC| models, respectively. It is unexpected to find that COMP is negatively associated with DER and |DIC|. This may be due to the fact that cash compensation in many Taiwanese firms is replaced with stocks or stock options in recent years. The coefficients of STOCK variable are -0.046(t=-4.27) and 0.003 (t=0.21) in the |DIC| and DER models, respectively. The coefficient of STOCK is negative statistically significant associated with |DIC| at 1% level. It implies that the interest conflict between shareholders and the managers holding large shareholdings is not severe and consistent with the argument of Jensen and Meckling (1976). However, in the DER model, the coefficient of STOCK is positive but not statistically significant. The coefficient of DEBT is 0.281(t=24.07), which proxy of leverage risk, is positive statistically significant associated with |DIC|. Consistent with the finding of DeFond & Jiambalvo (1994), this result reveals that the firms with higher leverage are more inclined to manipulate earnings. Table 5: Regression Results for Simultaneous Equations (n=1,834). | DIC |it 0 1DER it 2 COMPit 3STOCK it 4 DEBTit 5 RDit 6 FS it 7 IDR it 8 INDit 9 DPR it 10 FLEX it 11 | OCF |it 12 ROA it 13SIZE it 14 MILLS it it (1) DER it 0 1 | DIC |it 2 COMPit 3STOCK it 4 DEBTit 5 RDit 6 FS it 7 IDR it 8 INDit 9 QR it 10CYCLE it 11DIV _ YIELD it 12ST _ DEBTit 13MILLS it it (2) |DIC| Variables Expected sign Coefficients + DER COMP STOCK DEBT + + + + 3.067 -0.501 -0.046 0.281 *** RD FS IDR IND DPR FLEX + + + + + + 0.383 0.001 -0.148 -0.050 -0.009 1.631 *** |OCF| ROA SIZE QR CYCLE DIV_YIELD ST_DEBT MILLS + + + + + ? 0.362 -0.045 -0.003 *** Adjusted R2 F-statistic -0.059 *** Constant |DIC| -0.004 0.61 206.22 ** *** *** *** *** *** ** *** *** ** * *** DER t-stat. Coefficients -3.132 0.015 0.256 29.284 -2.426 -4.269 24.069 8.353 5.449 -5.509 -14.150 -2.442 8.382 -0.193 0.003 -0.054 -0.116 -0.0004 0.067 0.006 t-stat. *** *** 1.043 7.000 -0.667 0.206 -3.579 * -1.821 -1.345 1.512 1.170 *** 4.358 -2.368 0.071 0.130 -0.275 23.844 -2.776 -2.544 -1.675 0.005 -0.00004 0.006 0.001 -0.001 0.06 9.85 ** *** Legends: 1. MILLS is the inverse Mills ratio obtained from Equation (4). Other variables are defined in Table 3. 2. *, **, *** denote the significance on 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively, based on two-tailed tests. The coefficients of RD variable are 0.383(t=8.35) and -0.116(t=-1.82), which statistically significant at 1% and 10% level respectively, in the |DIC| and DER models. The statistically significant positive relation between R&D intensity and discretionary accruals reveals that managers with more growth opportunities tend to manage earnings to prevent underinvestment problems. However, the negative relationship between RD and DER suggests that the usage of financial instruments is decreased for managers with more growth opportunities. It is interesting to find that FS is statistically significant positively related with |DIC|, yet, statistically insignificant negatively related with DER. It implies that managers with higher exchange rate risk increase the use of discretionary accruals. However, a distinct pattern is revealed by the IDR variable empirical findings. The coefficients of IND variable are -0.050(t=-14.150) and 0.006(t=1.170) in the |DIC| and DER models, respectively. The empirical results reveal that the use of discretionary accruals is decreased for firms belonging to electronic industry when comparing with firms in other industries. Nevertheless, managers in electronic industry use slightly more financial instruments. The reason for this result may be attributed to the fact that there is strong demand for cash flow hedge for firms in electronic industry and managers use financial instruments to smooth cash flows volatility, then, decrease the usage of discretionary accruals. As to the exclusive variables in the |DIC| model, the coefficients of FLEX and |OCF| are 1.631(t=8.38) and 0.362(t=23.84), respectively, which are both positive and statistically significant at 1% level. It reveals that firms with more FLEX and larger magnitude of operation cash flows tend to use discretionary accruals to manipulate earnings. The coefficients of DPR, ROA and SIZE are -0.009(t=-2.44), -0.045 (t=-2.78) and -0.003(t=-2.54), both negative and statistically significant at 5%, 1% and 5% level, respectively. As to the exclusive variables in the DER model, the coefficient of QR variable is 0.005(t=4.36), positive and statistically significant at 1% level. The coefficient of CYCLE variable is -0.00004(t=-2.37), negative and statistically significant at 5% level. The coefficients of DIV_YIELD and ST_DEBT are statistically insignificant. ROBUSTNESS TEST The present study implements some diagnostic checks (untabulated) to confirm our initial findings. First, we know that three-stage least squares (3SLS) extend 2SLS and include all equations estimation at the same time. In order to gain confirmatory evidence to support our empirical results, the 3SLS regression is implemented in this study to estimate more efficient coefficients. The result of 3SLS regression reveals that the coefficients of DER in Equation (1) and |DIC| in Equation (2) are 0.689(t=2.74) and 0.079(t=2.15), both positive and statistically significant at 1% and 5% level, respectively. This additional evidence suggests our empirical result is robust to the 3SLS regression examination. Second, the present study further examines DER and |DIC| models independently by traditional ordinary least squares (OLS) to gain comparing evidence. These further examination results reveal that the coefficients of DER in Equation (1) and |DIC| in Equation (2) are 0.060(t=3.27) and 0.101(t=4.33), again, both positive and statistically significant at 1% level, respectively. The significantly positive relation between DER and |DIC| indicates that the primary results do not topple by separated OLS estimations of Equation (1) and (2). Third, the present study replaces the discretionary accruals measured from cross-sectional Jones (1991) model by the discretionary accruals measured from cross-sectional modified Jones model. In the 2SLS regressions, the coefficients of DER in Equation (1) and |DIC| in Equation (2) are 3.146(t=30.38) and 0.257(t=7.25), respectively, both positive and statistically significant at 1% level. In the 3SLS regressions, the coefficients of DER in Equation (1) and |DIC| in Equation (2) are 0.796(t=3.55) and 0.085(t=2.18), which are positive and statistically significant at 1% and 5% level in the |DIC| and DER models, respectively. The additional evidence suggests that the positive correlation between DER and |DIC| unlikely results from the misspecification of discretionary accruals. Finally, in order to gain comparative results with Barton (2001), we further use the stock concept to measure the position of financial instruments held by sample firms. Accordingly, DER variable is redefined as the sum of notional amount of financial assets and financial liabilities regulated by SFAS No.34 scaled by lagged total assets. The 2SLS regression empirical results show that the coefficients of DER and |DIC| are 0.988 (t=13.32) and 0.220(t=4.73), respectively, when discretionary is measured by Jones model. Alternative, the 2SLS regression empirical results report the coefficients of DER and |DIC| are 1.039 (t=13.95) and 0.224(t=4.97), respectively, when discretionary is measured by modified Jones model. In summary, we obtain supportive evidence on our hypothesis that managers view derivatives and discretionary accruals as partial complement tools in enhancing earnings. The above additional diagnostic checks demonstrate that our empirical results are robust to different estimating methods and specifications of variables. CONCLUSION Prior studies document that firms can use derivative instruments to speculate and/or to arbitrage on private information, yet, few studies highlight the risk hedging motive and ignore the important roles of the other two key participants. Adam & Fernando (2006) argue that the active usage of derivatives is thought to add value by alleviating a variety of market imperfections through hedging. Gèczy et al. (2007) also suggest that financial derivatives involve real action which plays an important role in strategically boosting firm’s earnings and view speculation as a positive profitability activity. Although Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005) evidence managers appear to trade-off derivatives and discretionary accruals for incentives to smooth earnings. The present study alternatively use the financial instruments usage regulated under SFAS No.34 in Taiwan to examine the hypothetical complement relationship between financial instruments usage and discretionary accruals in enhancing earnings. The empirical result indicates that financial instruments usage is positive associated with the magnitude of discretionary accruals and supports our complement hypothesis. It suggests that managers use financial instruments and discretionary accruals jointly to increase earnings, contrary to the conclusions of Barton (2001) and Wang & Kao (2005). Our empirical results to some extent evidence the possible potential multi-purposes of financial instruments usage and support the findings of Sapra (2002). These results remain robust to various specification tests. REFERENCE 1. 2. 3. Adam, T. R., and C. S. Fernando. (2006) Hedging, Speculation and Shareholder Value, Journal of Financial Economics. 81 (2), 283-309. Allayannis, G., and E. Ofek. (2001) Exchange Rate Exposure, Hedging, and the Use of Foreign Currency Derivatives, Journal of International Money & Finance. 20(2), 273-296. Baber, W. R., P. M. Fairfield, and J. A. Haggard. (1991) The Effect of Concern about Reported Income on Discretionary Spending Decisions: The Case of Research and Development, The Accounting Review. 66(4), 818-829. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. Barton, J. (2001) Does the Use of Financial Derivatives Affect Earnings Management Decision? The Accounting Review. 76(1) , 1-26. Bartov, E., F. A. Gul, and S. L. Tsui. (2001) Discretionary-accruals Models and Audit Qualifications, Journal of Accounting and Economics. 30(3), 421-452. Bowen, R.M., L. DuCharme, and D. Shores (1995) Stakeholders' Implicit Claims and Accounting Method Choice, Journal of Accounting and Economics. 20(3), 255-295. Breeden, D., and S. Viswanathan (1998) Why Do Firms Hedge? An Asymmetric Information Model. Working Paper, Duke University. Brown, G.W., P. R. Crabb, and D. Haushalter (2006) Are Firms Successful at Selective Hedging? Journal of Business. 79(6), 2925-2949. Chang, W.J., L.T. Chou, and H.W. Lin (2003) Consecutive Changes in Insider Holdings and Earnings Management, International Journal of Accounting Studies. 37, 53-83. (In Chinese) Dadalt, P., G. Gay, and J. Nam (2002) Asymmetric Information and Corporate Derivatives Use, The Journal of Futures Markets. 22(3), 241-267. Dechow, R., G. Sloan, and A. Sweeney (1995) Detecting Earnings Management, The Accounting Review. 70(2), 193-225. DeFond, M. L., and J. Jiambalvo (1994) Debt Covenant Violation and Manipulation of Accruals, Journal of Accounting and Economics. 17(1), 145-176. Defond, M. L., and C. W. Park (1997) Smoothing Income in Anticipation of Future Earnings, Journal of Accounting and Economics. 23(2), 115-139. DeMarzo, P., and D. Duffie (1995) Corporate Incentives for Hedging and Hedge Accounting, Review of Financial Studies. 8(3), 743-771. Faulkender, M. (2005) Hedging or Market Timing? Selecting the Interest Rate Exposure of Corporate Debt, Journal of Finance. 60(2), 931-962. Froot, K.A., D.S. Scharfstein, and J. C. Stein (1993) Risk Management: Coordinating Corporate Investment and Financing Policies, Journal of Finance. 48(5), 1629-1658. Gèczy, C., B. A. Minton, and C. Schrand (1997) Why Firms Use Currency Derivatives, Journal of Finance. 52(4), 1323-1334. Gèczy, C. C., B. A. Minton, and C. M. Schrand (2007) Taking a View: Corporate Speculation, Governance, and Compensation, Journal of Finance. 62(5), 2405-2443. Graham, J. R., and D. A. Rogers (2002) Do Firms Hedge in Response to Tax Incentives? Journal of Finance. 57(2), 815-839. Greene, W. H. (2004) Econometric Analysis 4th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Heckman, J. J. (1979) Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error, Econometrica. 47, 153-162. Healy, P.M., and K. G. Palepu (1993) The Effect of Firms' Financial Disclosure Policies on Stock Prices, Accounting Horizons, 7(1), 1-11. Jensen, M., and W. H. Meckling (1976) Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics. 3(4), 305-360. Jones, J. (1991) Earnings Management during Import Relief Investigations, Journal of Accounting Research. 29(2), 193-228. Jorion, P. (1990) The Exchange Rate Exposure of U.S. Multinationals, Journal of Business. 63(3), 331-345. Kim, Y.S., I. Mathur, and J. Nam (2006) Is Operational Hedging a Substitute for or a Complement to Financial Hedging? Journal of Corporate Finance. 12(4), 834-853. Kothari, S.P., A.J. Leone, and C. E. Wasley (2005) Performance Matched Discretionary Accrual Measures, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163-197. Nance, D. R., C. W. Smith Jr., and C. W. Smithson (1993) On the Determinants of Corporate Hedging, Journal of Finance. 48(1), 267-284. 29. Neter, J., W. Wasserman, and M. H. Kutner. (1989) Applied Linear Regression Models. Irwin: Homewood. 30. Petersen, M. A., and S. R. Thiagarjan (2000) Risk Measurement and Hedging: with and without Derivatives, Financial Management. 29(4), 5-30. 31. Pincus, M., and S. Rajgopal (2002) The Interaction of Accounting Policy Choice and Hedging: Evidence from Oil and Gas Firms, The Accounting Review. 77(1), 127-160. 32. Sapra, H. (2002) Do Mandatory Hedge Disclosures Discourage or Encourage Excessive Speculation? Journal of Accounting Research. 40(3), 933-964. 33. Schrand, C., and H. Unal (1998) Hedging and Coordinated Risk Management: Evidence from Thrift Conversions, Journal of Finance. 53(3), 979-1013. 34. Smith, C.W., and R.M. Stulz (1985) The Determinants of Firms’ Hedging Policies, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 20(4), 391-405. 35. Stulz, R. (1996) Rethinking Risk Management, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. 9(3), 8-24. 36. Subramanyam, K.R. (1996) The Pricing of Discretionary Accruals, Journal of Accounting and Economics. 22(1/3), 249-281. 37. Tufano, P. (1996) Who Manage Risk? An Empirical Examination of Risk Management Practices in the Gold Mining Industry, Journal of Finance 51(4), 1097-1137. 38. Watts, R. L., and J. L. Zimmerman (1986) Positive Accounting Theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs. 39. Wang, W., and S. H. Kao (2005) Discretionary Accruals, Derivatives and Income Smoothing, Taiwan Accounting Review. 5(2), 143-168.