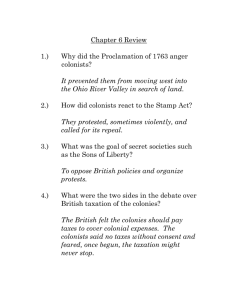

Page Name: Social Studies Seven/PD: _____ Chapter Four/Part

advertisement

Page 1 Name: ________________________________ Social Studies Seven/PD: _____ Chapter Four/Part One – The Road to Rebellion I. The Road to Rebellion A. The Committees of Correspondence: Sam Adams’ efforts to spread the news of the Boston Massacre to all 13 Colonies marked the beginning of the heavy use of the Committees of Correspondence. Colonists carefully watched British actions (laws, taxes, court cases, the arrival and movement of soldiers, and British officials), recorded what they observed, and spread the news through the committees in each colony. Adams understood that he needed to find ways to maintain Colonial anger against the British. The committees were very helpful in this regard. EFFECTS: Although the committees were a peaceful organization, they formed the beginnings of a much more valuable and deadly tool that would be used to great effect in the future. They were perfect “spy rings”, or groups of spies. During the Revolutionary War, former members of the committees helped the United States Army gather information on British troop movements. At times, the information gathered was enough to save the Army from defeat or enough to allow the Army to defeat the British in battle. B. Britain Cancels Taxes: On the very day that the Boston Massacre took place, Parliament again cancelled taxes on the 13 Colonies. The Nonimportation Agreements (Colonial boycott) had hurt merchants Britain, who again forced Parliament to cancel taxes. The Quartering Act was cancelled and the majority of the taxes that angered Colonists were also repealed. King George III, however, did ask for one tax to stay in place – the tax on tea. The King believed, and Parliament agreed, that Britain still had to show that it had the right to tax the Colonies. EFFECTS: The cancellation of the Quartering Act and many British taxes pleased the people of the 13 Colonies. Once again, they had united and forced Great Britain to back down. Colonists, however, still wondered about the future and worried that their rights were threatened. The issue of Britain’s right to tax had not been settled and memories of British actions such as the dismissal of Colonial Assemblies, the writs of assistance, and the Boston Massacre were still fresh in the minds of Colonists. Britain still made no offer to allow the Colonial Assemblies to vote on taxes or to give the Colonies representation in Parliament. As a result, little or nothing had been done to resolve the issue that was at the heart of Colonial protests – representation. Britain felt that the cancellation of taxes (both the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts) was more than generous and did not (or could) not understand that the troubles with the Colonists had only been postponed – not solved. Page 2 C. An Uneasy Peace: The timely cancellation of taxes helped to calm the 13 Colonies after the uproar over the Boston Massacre. Britain had come to the decision that the Colonies needed time to settle down and the British Government did not want to do anything to create further anger. No new taxes were proposed in Parliament and British officials in the 13 Colonies did not take any threatening actions. Anger remained fairly strong in New England. The Middle Colonies were another story, however. Other than New York, where the Colonial Assembly had been dismissed for protesting against the Quartering Act, the people of the Middle Colonies did not feel overly threatened by Britain. A minority of the population of the Middle Colonies was unhappy enough to want independence – mostly people on the frontier. People on the frontier were under threat of Indian attacks and still felt that Britain was not doing enough to protect them. The mood was entirely different in the Southern Colonies. British taxes had done little to harm Southern cash crop exports and no Southern Colonial Assembly had been dismissed. The wealthiest Southerners (planters) remained very loyal to Britain and few in the colonial governments of the South considered independence from Britain. The only Southern Colony that had a strong anti-British following was Virginia, where men like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry remained concerned about British actions. EFFECTS: As 1770 came to a close (the year of the Boston Massacre), the 13 Colonies were not ready to break free from British control. War and independence was on the minds of only a few Colonists. For the majority of the people in the Colonies, independence from Britain was still unthinkable. Colonists, although angry and concerned, wanted to work out their differences with Britain peacefully and remain a part of the British Empire. D. Britain Passes The Tea Act in 1773: Britain’s tax on tea, as symbol of the government’s right to tax the Colonies, did not create a violent reaction. Large numbers of Colonists still refused to buy British tea in quiet protest. The tax that represented Britain’s right to tax quickly became a financial nightmare. Tea was imported into the 13 Colonies by the British East India Company. The tea was sold to Colonial merchants and was then sold directly to Colonists. Colonial merchants had to raise the price of tea in order to make a profit as tea sales declined. When Colonists refused to buy the tea, it began to build up in the warehouses of the East India Company. By 1773 the company had 15 million pounds of tea in storage and the company, one of Britain’s largest, was beginning to fail. Parliament decided to come to the aid of the East India Company by passing the Tea Act in 1773. Under the Tea Act, tea would be sold directly to Colonists without going through Colonial merchants, saving the Colonists money even though the tax on tea was still in place. Page 3 EFFECTS: Britain was shocked once again when the 13 Colonies erupted in protest. Colonial merchants could be put out of business by British policies and Colonists saw this as a sign that Britain was now taking away the Colonial right to “free enterprise” or to conduct business without government interference. Other Colonists saw the act as a trick to get the Colonies to accept the British tax on tea. A new boycott was created against tea, the Daughters of Liberty began to serve coffee in its place, and the Sons of Liberty actually prevented the unloading of tea in many harbors. E. The Boston Tea Party: The boycott on tea lasted through much of 1773 and the situation with Britain’s East India Company grew worse by the day. Tea ships in harbors were reluctant to unload their tea with crowds of angry Colonists on shore and threats from the Sons of Liberty ringing in their ears. In late November of 1773, three tea ships arrived in Boston Harbor and Governor Thomas Hutchinson demanded that they be unloaded. Hutchinson was a well-known Loyalist, or supporter of Great Britain. The Sons of Liberty and other Patriots (supporters of independence for the 13 Colonies) warned that the cargo should not be unloaded under any circumstances. When it became clear that Hutchinson intended to unload the cargo, Sam Adams organized a meeting in Boston’s Old South Meetinghouse on December 16. Once more, Adams sent a note to the governor demanding that the tea be kept aboard the ships. When word came back to the meeting that the governor intended to unload the tea the following morning, Adams yelled, “This meeting can do no further to save the country.” Adams’ statement was a preplanned signal that triggered one of the most famous events in American History. Men burst through the doors dressed as Indians, voices from the gallery above the meeting called “Boston Harbor a teapot tonight! The Mohawks are come!” and the lights went out in the meeting hall. Several British Army officers who had arrived to keep an eye on Adams were run over as the “Indians” and other Patriots ran out of the meetinghouse. The crowd, which soon grew to hundreds and then thousands, moved towards the docks and the tea ships. The “Mohawks” boarded the ships, hacked open the tea chests with tomahawks, and dumped the tea into the harbor to the cheers of the crowd on shore. In the space of an hour, thousands of pounds (dollars) of tea had been destroyed. The Sons of Liberty had sent a message to Britain that could not be ignored. Colonists had no intentions of paying taxes that were passed without their approval and that threatened to ruin their businesses. In fact, they were willing to take drastic actions to prove their point. EFFECTS: In general, people were shocked by the destruction of tea in Boston. Many in the Colonies thought that the Sons of Liberty had gone too far and that a breakdown in law would follow. Many others were thrilled with the Tea Party and felt that taking greater action against Britain and its taxes was long overdue. The Tea Party helped to win the support of many Colonists to the “patriot cause” (struggle for independence). People sensed that a change had taken place – the 13 Colonies were openly defying Great Britain. In his diary, John Adams wrote down his reaction to the Boston Tea Party: Page 4 “This destruction of the tea is so bold, so daring, so firm . . . it must have such important and lasting results that I can’t help considering it a turning point in history.” In Britain, the reaction was very different. The British were furious with this outright act of defiance against the authority of the King and the Government. The King was personally offended and members of Parliament (as well as ordinary British citizens) who had sympathized with the Colonists in the past were outraged. King George III ordered Parliament to punish Massachusetts for the Tea Party and what it represented – a loss of British control over the 13 Colonies. No thought was given to backing down and giving the 13 Colonies representation in Parliament or to allowing Colonial Assemblies to vote on taxes. The famed “Boston Tea Party” December 16, 1773 Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson Flag of the British East India Company – the company that shipped tea to the 13 Colonies Page 5 Review Questions 1. In what way were the Committees of Correspondence “very helpful?” 2. What was “unthinkable” for a majority of the people in the 13 Colonies, even after the Boston Massacre? 3. The Tea Party was a message from the Sons of Liberty to Great Britain. What was that message? 4. What did the Boston Tea Party helped to win? 5. In Great Britain, what did the King and Parliament feel that the Boston Tea Party represented? Page 6 Name: ______________________________ Social Studies Seven/PD: _____ Chapter Four/Part Two – Rebellion II. Rebellion A. The “Intolerable Acts”: Both Parliament and the King of Britain came to the decision after the Boston Tea Party that Massachusetts must be punished and that Britain must show that it was in control. Britain’s right to tax the Colonies was to be settled. In the minds of the King and the members of Parliament, it was time to show the 13 Colonies that Great Britain was to be obeyed. In 1774, Parliament passed a series of harsh new laws that were designed to punish Massachusetts in general and Boston in particular. The new laws were considered to be so harsh by the Colonists that they named them the “Intolerable Acts.” The first law shut down Boston Harbor to all ships entering or leaving the harbor. Not even a fishing boat would be allowed to leave and return. British warships blocked the mouth of the harbor and customs officers kept a close guard over ships tied up at the docks. The harbor was to remain closed until the tea that had been destroyed was paid for in full. Furthermore, Boston was to repay British officials for any property that had been destroyed by “Patriots.” Finally, the City of Boston was expected to show that it was sorry for what had happened before the harbor could be reopened. A second law made it illegal to hold more than one town meeting a year in any Massachusetts town unless written permission was given by the governor. Town meetings were considered to be one of the most important rights (the right to assemble) in the New England Colonies. In addition, all trial juries would be selected by officials of the British Government and could not be elected by Colonial citizens. Colonists wondered if it would be possible to receive a fair trial when British officials selected the jurors. The third law allowed customs officers and other British officials who were charged with a crime to be tried in Britain or Canada instead of Massachusetts. The laws made Colonists feel that a British official could commit a crime and “get away with it.” Juries in Britain and Canada were far more likely to find a British official innocent than a jury in Massachusetts. Finally, the fourth law was a new Quartering Act. British soldiers would no longer have to sleep in tents in the open parks of Boston. Colonists would now be forced to take soldiers into their own homes when no other form of housing was available. The citizens of Boston faced a loss of privacy, damage to their homes, and poor treatment by British soldiers. British soldiers had a reputation for roughness and poor manners. The thought of a squad of British soldiers in their homes struck fear into the hearts of Bostonians. Page 7 EFFECTS: The Intolerable Acts convinced the people of Massachusetts and the other Colonies that Britain truly meant to take away Colonial rights. The new laws threatened to destroy all business in Boston and create a shortage of food by closing the harbor down. British officials were likely to be found innocent of crimes while Colonists were likely to be found guilty. Soldiers could invade the privacy and peace of Colonial homes. The laws created enormous anger in Massachusetts – an anger that spread to the other Colonies as the committees of correspondence spread the news. People from the other 12 Colonies began to send food to Boston to help the city while the port was closed. Citizens throughout the 13 Colonies wondered if they might also lose their rights and face severe punishment from Britain. B. The Quebec Act Shortly after the Intolerable Acts were passed, news reached the 13 Colonies that another act had been passed. The Quebec Act was created by Parliament to give Canadians (many of whom were French Catholics) complete religious freedom. In addition, the law gave Canada all of the lands along the Ohio and Missouri Rivers – land that had been claimed by Colonists such as George Washington. Finally, the new act gave Canadians the beginnings of independent rule. EFFECTS: Colonists were very unhappy with the Quebec Act. Many saw it as a reward to their former enemies of the French and Indian War. Worse, the act gave away lands that Colonists had fought for during the French and Indian War. People in Canada were being given rights even as citizens in the 13 Colonies were losing their rights. Colonists considered the Quebec Act to be an insult and were shocked that Britain would treat a former enemy better than its own “British” citizens. C. The First Continental Congress: News of the Intolerable Acts spread quickly through the 13 Colonies thanks to the efforts of the Committees of Correspondence. The reaction across the Colonies was one of anger and fear. The Virginia Assembly called for a day to be set aside to mark the “shame” of the Intolerable Acts. Other Colonies pledged to support Massachusetts and oppose the British laws. Anger and fear forced 12 of the 13 Colonies to hold another meeting in Philadelphia known as the First Continental Congress. The delegates at the Congress met to discuss what the Colonies would do about the harsh Intolerable Acts and the insulting Quebec Act. Delegates such as Sam Adams and John Adams urged that the Colonies should break from Great Britain, but they were in the minority. Despite all that had happened, most of the delegates were still unwilling to risk a war with Great Britain or break from their parent country. Page 8 The delegates at the Continental Congress decided to: 1. 2. 3. 4. Boycott all British goods until the Intolerable Acts were cancelled. Support Massachusetts by sending food and other items to help the City of Boston while the port was closed. Encourage all Colonies to create an emergency militia force and begin training them The delegates agreed to meet in May of 1775 to discuss further action at a Second Continental Congress EFFECT: The forming of militia’s was viewed as a potential preparation for war by Great Britain and Britain intended to bring the 13 Colonies under control as quickly as possible. Britain’s commanding officer in Boston, General Gage, decided to raid and capture or destroy stores of weapons in towns outside of Boston to prevent future fights. The raid was set for the night of April 18-19, 1775. D. Lexington and Concord: The Sons of Liberty and the Committees of Correspondence kept a close watch on British troops in Boston. Colonials working in the stables where British officers kept their horses were ordered to have the horses saddled and prepared to ride late at night on April 18, 1775. Other Colonists working in and near British headquarters in Boston overheard that a large number of soldiers would leave Boston “by surprise” and move to capture the militia weapons being gathered at the small towns of Lexington and Concord. They also planned to arrest Sam Adams and John Hancock. All of this information was reported to Patriot leaders before they reached many of the British officers who would participate in the movement! A quick plan was created to alert a small group of men across the river from Boston who waited to ride to Lexington and Concord to spread the news that the British were on the move. One lantern would be placed in the tower of Boston’s Old North Church if the British were leaving Boston by land. Two would appear if they crossed the river in boats. Shortly after midnight, the three riders saw two lanterns and sped down different roads to make certain the news reached Lexington and Concord. The three riders were named Dawes, Prescott, and Paul Revere. They shouted, “the Regulars are coming” as they passed through towns to alert militia units along the way. During the night, 800 well- trained and equipped British soldiers marched to the village of Concord and found 70 “minutemen” (men who could be ready for action in 60 seconds) under the command of Massachusetts Captain John Parker blocking the road. The British officer in charge, who had been told to avoid a confrontation, ordered the minutemen to move. In the silence that followed, a musket fired (to this day, we do not know which side fired first) and the nervous British troops opened fire without their officers command. Page 9 By the time the British officers got their men back under control, eight Colonists lay dead and the rest of the minutemen had scattered to warn militia units in the surrounding towns about what had happened. The British moved on to Lexington, finding very few weapons and failing to capture Sam Adams or John Hancock. Militia units coming from all directions then attacked the British and drove them back to Boston in a day-long bloody fight that left 73 soldiers dead and 200 wounded. The militiamen had been driven into a fury by news of the deaths at Concord and they had turned their fury loose on the British. EFFECTS: The opening shot at Concord has since been known as the “shot heard round the world” for its importance in history. The fighting at Lexington and Concord meant that the 13 Colonies were now in a state of open and violent rebellion against Great Britain and could now expect the British to strike back with all of their strength. A hard decision lay ahead for the Colonists who were to meet at the Second Continental Congress in May. Would they try to make peace with Britain or declare independence? General Thomas Gage Commader of British forces in Boston Margaret Kemble Gage Wife of General Gage – she may have passed British plans to Dr. Warren of Colonial Intelligence William Dawes, Jr. One of the Patriot night riders to Lexington and Concord Page 10 Review Questions 1. What did Great Britain decide to do after the Boston Tea Party? 2. What did the Intolerable Acts convince many people of in the 13 Colonies? 3. What did the delegates to the First Continental Congress decide to do in response to the Intolerable Acts (four steps)? 4. How did the British react to the forming of Colonial militia forces (what did the British decide to do)? 5. Which “hard decision” did the Colonies have to make after the fighting at Lexington and Concord? Page 11 Quebec Act of 1774 Revisited Within the 13 Colonies the Quebec Act was actually considered to be a part of the Coercive Acts passed by Parliament to punish the Massachusetts for its actions during the Boston tea Party. The Quebec Act was not part of the Coercive Acts but this made little difference to Colonists as it was passed at the same time as the Coercive Acts. The Quebec Act contained the following provisions: The province of Quebec was expanded to include part of the “Indian Reserve.” This included much of present-day southern Ontario (Canada), Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. The oath of allegiance was replaced with one that did not mention the Protestant faith. This allowed French-Catholic residents of Quebec to hold government offices and participate in governing the colony. It guaranteed religious toleration for Catholics and the right of the Catholic Church to collect tithes (taxes). It allowed the use of the French civil law for private (civil) matters, and used English common law for government use and criminal prosecution. The Colonial Government of Quebec consisted of a Governor appointed directly by Britain with a legislative council to advise him without the use of any elected assembly. EFFECTS: The Quebec Act alarmed people in the 13 Colonies. Many saw it as the new British “plan” for governing its colonies by direct rule and without the use of elected assemblies. They feared that Great Britain would eventually strip the 13 Colonies of their elected assemblies and eliminate the ability of colonial citizens to participate in governing themselves. Colonists also saw the transfer of territory to Quebec as a possible permanent ban of settlement to the west of the Appalachian Mountains. Page 12 Name: __________________________________ Social Studies Seven/PD: _____ Chapter Four/Part Three – The “Unofficial War” III. The “Unofficial War” A. Rebellion Without War (April 1775-July 1776): After the fighting at Lexington and Concord in April of 1775, Colonists realized that a war with Great Britain was likely. There was, however, no official declaration of war or declaration of independence. For that matter, there was no Colonial Government – the Second Continental Congress was not scheduled to meet until May of 1775. In America, Colonists waited for the decision of the delegates to the Second Continental Congress that would meet in Philadelphia. Fear and high emotions swept the Colonies – ranging from those who wanted independence and war to others who wished for peace with Britain at any cost. When news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord arrived in June of 1775, British officials in America and Great Britain considered Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. Obviously, the rebellion would have to be contained before it could spread to the other twelve colonies. The British Governors in the 13 Colonies did not have the authority to act outside the borders of their own colonies and they (as well as British Army and Navy commanders) waited for word to arrive from Great Britain before taking action. Loyalist citizens in America nervously waited for help to arrive from Great Britain. B. The Fall of Fort Ticonderoga: During this time (spring and summer of 1775), a group of militiamen led by a New Hampshire woodsman named Ethan Allen and a wealthy Connecticut merchant – Benedict Arnold, decided to attack Ft. Ticonderoga at the southern end of Lake Champlain in New York. Allen and Arnold wished to capture the large supply of cannon, gunpowder, and muskets at the fort. The Patriot leaders also believed that capturing the fort would give them control over Lake Champlain – an invasion route both into and out of the Colonies. The fort and its supplies were captured in a surprise night attack and without loss of life. News of Lexington and Concord had not arrived at the fort and the gates were wide open on the night of the attack – with one guard asleep at his post! Enemy Natives had not been in the area for years and the entire garrison was captured while asleep. The fort’s commander was humiliated when he was forced to surrender in his nightclothes (pajamas) to Ethan Allen. EFFECTS: The Americans captured a large supply of cannon, muskets, and gunpowder and now could use Lake Champlain in an attempt to invade Canada. The 13 Colonies would also be able to block any attempt by British soldiers to invade the Colonies from Canada. Capturing the fort was one further step towards a final break with Britain and the beginning of a true war. Page 13 C. Peace or War? When the news arrived, the delegates to the Second Continental Congress were shocked by the capture of Fort Ticonderoga (some wanted the weapons returned to the British while others saw it as a great victory). Everyone knew that a decision had to be made before the fighting continued between the 13 Colonies and Great Britain. After lengthy debate, the divided Congress agreed on two actions: EFFECTS: 1. Olive Branch Petition: Members that wanted to repair relations with Britain forced the Second Continental Congress to send King George III a letter in which the 13 Colonies declared their loyalty to the King and asked the King to repeal the Intolerable Acts as a gesture of peace. In return, the Colonies would lay down their weapons and remain a part of the British Empire. 2. Continental Army: The more realistic members knew that a peaceful restoration of relations with Britain was very unlikely. They convinced Congress to create an army (the Continental Army) in the event that King George III rejected the Olive Branch Petition. John Adams succeeded in having George Washington appointed commander of the army – a calculated move to win the support of the Southern Colonies. In effect, The Second Continental Congress asked for peace while it prepared for war! D. The Battle of Bunker Hill: Before an answer on the Olive Branch Petition arrived from Britain and George Washington could take command of the Continental Army outside Boston, militia commanders in Massachusetts decided to take matters into their own hands. In June of 1775, the Massachusetts militia decided to provoke (start) a fight with the British forces in Boston. Militia Colonel William Prescott moved 1,200 militiamen onto a hill (Breeds Hill) overlooking the harbor, knowing that the British commander in Boston (General Howe) would have to attack him before he and his men could move cannon onto the hill and begin firing on the city and its harbor. When the British attacked the next day, Howe rejected a plan to move behind and surround the Americans on the hill. He wanted to attack by going straight up the hill – sending the message that Britain would crush the rebellion with superior military force. The attack, however, took most of the day and resulted in over 1,000 British dead and wounded before the Americans ran out of gunpowder and retreated. EFFECTS: The Battle of Bunker Hill let the British know that Americans could fight very hard and would not be easy to defeat. The Americans learned that the British would also fight very hard and were not going to let the Colonies become independent after one tough battle. Both sides realized that the coming war would be long and difficult. Page 14 E. Retreat and Blockade: When Washington arrived to take command of the Continental Army in the summer of 1775, he found it to be in terrible shape – lacking supplies, weapons, gunpowder, training, and leadership. He realized that he could do little with the army but begin to train it and try to turn it into a true fighting army. The new commander was so shocked by what he saw that he was left speechless and wondered whether he had made the greatest mistake in his life by agreeing to take command. Washington dared not to attack the British, so he simply surrounded Boston and waited for cannon to arrive. During the winter of 1776, Washington ordered General Henry Knox, his chief of Artillery, to move the cannon from Ft. Ticonderoga to the Continental Army positions outside Boston. Knox knew that he could not move the large cannon (some weighed several tons) down the small country roads of New York and Massachusetts and decided to wait for a thick layer of snow to form. He then had the cannon loaded on large sleds and pulled them to Boston by horse and ox teams. Washington placed the cannon on the hills around Boston Harbor even though he had very little powder or cannon balls to fire from them. When the British commander in Boston saw the cannon, he believed that it was hopeless to try to defend Boston and abandoned the city – moving all of his soldiers and Loyalist Americans to Canada by ship. Although it was a great victory for the Americans, the British blockade (ring of ships outside Boston Harbor) remained unbroken and Washington knew that the British would be back – most likely targeting New York City. EFFECTS: The capture of Boston by American forces was another step towards war with Great Britain. Public opinion on independence began to shift, with many Americans beginning to feel that a war with Britain could not be avoided and that the Colonies needed to prepare for the eventual British attack. The Americans won a city, but were cut off from supplies and trade with foreign nations. Washington faced the very difficult job of turning an army of volunteer farmer/soldiers into a fighting force that could face down the greatest military power on the planet. The lack of money, supplies, and military experience that existed in the Colonies guaranteed that this would be nearly impossible in the near future. Washington also had to face the unpleasant fact that Britain could use its navy to strike anywhere and at any time. In fact, Britain did use its navy to blockade the entire Atlantic coastline. F. Disaster in Canada: In late 1775, two small American Armies were sent to invade Canada and capture Quebec. The Americans hoped that the Canadians would rebel and join them in attacking the British. Colonial leaders also hoped that that the capture of Quebec would stop British plans to invade the colonies from Canada. The attack, however, ran into bad weather and the armies began to suffer from hunger, cold, and disease. When the two groups joined and attacked Quebec on the last day of 1775, they were defeated and had to wait outside the city until May of 1776 before what was left of the force retreated to the Colonies. Page 15 EFFECT: Britain remained in control of Canada and could launch invasions into the Colonies at any time. The Americans also realized that the citizens of Canada would not turn against the British and join the Colonies in a war for independence. Instead, the Colonies would be forced to fight alone until an ally could be found. As 1776 began, the delegates at the Second Continental Congress realized that the situation was spinning out of control. Many in Congress began to seriously consider declaring independence from Great Britain. Ethan Allen Leader of the Green Mountain Boys Benedict Arnold Colonial merchant turned soldier Henry Knox Bookseller turned soldier Page Five Page 16 British General William Howe – Commander of British forces in Boston who ordered the attack on Bunker Hill The death of Dr. Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill (inaccurate – Dr. Warren was actually shot while retreating) Traditional view of the British assault on Bunker Hill (also believed to be inaccurate for several reasons) Page 17 Review Questions 1. What did the capture of Fort Ticonderoga give the 13 Colonies? (two things): 2. After the capture of Ticonderoga, the Second Continental Congress decided to: (two ideas) 3. The Battle of Bunker Hill taught both sides (Britain and the Colonies) that: 4. What did the capture of Boston do to public opinion in the Colonies? 5. How did Britain use its navy after the loss of Boston? Page 18 Name: _________________________________ Social Studies Seven/PD: _____ Chapter Four/Part Four: Independence Declared IV. Independence Declared A. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense Persuades Americans: In early 1776, an English immigrant (sent to America by Benjamin Franklin) wrote a short pamphlet with the title of Common Sense. The title suggested that it would not be difficult to read and over 500,000 copies were sold in a land of only 3,000,000 people - one pamphlet for every six citizens. Paine took the feelings held by many in America and put them into simple arguments and statements that made sense to all – not just the well-educated. Paine argued that: - America no longer needed to be ruled by a King - Americans had “grown up” and were capable of ruling themselves - Britain was too far away (3,000 miles) to govern America effectively – it simply took too long for news and important information to travel back and forth between England and America - America did not need Great Britain to be able to trade and make money – the world would buy our food and other products whether we were “British” or “American” EFFECTS: Paine put the feelings of many Americans into words and created an argument that convinced thousands of Colonists to join the “Patriot” cause against Great Britain. The pamphlet had the greatest effect on the undecided – those who could not decide whether to remain loyal to Britain or fight against Britain for independence. The pamphlet also made an enormous change in the way people felt about kings and queens. For the first time, people began to openly question the need for a king. Many Americans decided that a king or queen was not needed – the people could run their own affairs without one. After all, the 13 Colonies had governed themselves until the end of the French and Indian War and they could govern themselves once more. B. Independence Declared: When news reached the 13 Colonies that King George had rejected the Olive Branch Petition and planned to send a huge army to “crush the rebellion,” the Continental Congress realized that it had to take action. In June of 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee asked the Congress to consider declaring independence from Great Britain – a move that was approved that day. Page 19 A committee of five men was appointed to write a “Declaration of Independence” and it included a young Virginian named Thomas Jefferson, John Adams of Massachusetts, and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. Once again, John Adams (who had recommended Washington to command the Continental Army) felt that the main job of writing the declaration should be given to a southerner to win southern support. Jefferson’s declaration was approved after changes on July 2, 1776 and formally signed and recognized on July 4, 1776. EFFECT: The Declaration of Independence announced the creation of the United States of America and its approval by Congress marked the official beginning of our nations’ history. The Declaration is also one of the most important documents in world history – starting revolutions against kings and queens around the globe. People around the world began to believe that they had a right to rule themselves. The age of kings and queens began to slowly decline from this point forward. C. Uncertain Times and Disaster at the Battle of Long Island: The Declaration of Independence changed many things in America. The British Government, complete with its governors, judges courts, clerks, tax collectors, soldiers, and ships was gone. The new government, led by the Second Continental Congress, had to find a way to run a nation. There was no King or President and Congress only had the power to run the military and conduct relations with foreign nations. Congress could not raise taxes or take soldiers from the states – it could only ask for money, men, and supplies. The government quickly set about trying to prepare for the coming war, but it was a job made difficult by lack of money and lack of cooperation from the states. Congress took the drastic step of designing and printing its own money known as “Continental Dollars” – money that was not backed by gold or silver and had little real value. Ambassadors were sent to foreign nations (especially France) to ask for both loans and military help. In July of 1776, Congress ordered Washington to take his 20,000 men to defend New York City against a British invasion force of 34,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors, 30 major warships, and 400 transport ships. Washington knew that the city would be difficult to defend without ships of his own, but did his best to prepare for the attack. In August of 1776, the British smashed the Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island – killing, capturing, and wounding 1,400 American soldiers. The American Army only escaped complete destruction by leaving Long Island in rowboats during a night thunderstorm and a thick fog. EFFECT: Washington was forced to concentrate on keeping his army alive but was not strong enough to attack the British. His only goal was to keep the army together until it was strong enough to attack. The fighting now shifted from New England to the Middle Colonies as Washington’s Army was chased down and relentlessly attacked by the British. Throughout the fall and into the winter, the British gave the Continental Army little time to rest, train, or find new supplies. Many believed that the Revolution had already failed. Page 20 D. Dark Times for the United States: There was little doubt that the United States was not well prepared to fight a war against the greatest power on the face of the earth. Washington’s defeat at Long Island and his loss of New York City seemed by many to be proof that the Revolution would not last long and that the United States would be brought back under British control in short order. Around the world, other nations watched the struggle with interest, but could not see how a nation of three million farmers could defeat the mighty British Empire. In nearly every way, the United States was at a great disadvantage in its struggle with Britain. The new nation had only a tiny fraction of Britain’s wealth, population, industry, or military strength. There were very few men with formal military training or experience in the United States. Even George Washington had never been a part of the regular British Army. The United States had no navy to speak of – only a small number of converted merchant ships that could hardly challenge the overwhelming power of the Royal Navy or break its blockade of the coastline. The lack of industry and money meant that the United States could not afford to pay, supply, and train a large army. Instead, the new nation had to hope that each state would do its best to raise as many soldiers as possible. Congress, as the national Government, could do little to actually force any state to do anything. Congress could only ask for men, supplies, and money from the states. In effect, each state was like an independent nation and they seldom acted together in a coordinated way. Despite all of the disadvantages, the United States did have some hope. The war was to be fought in America – and few knew the land as well as the Americans did. Americans would literally be fighting to protect their homes and families. They were also willing to fight an “irregular” war. Unlike their enemy, many Americans would be willing to use Native tactics and wished to avoid fighting the British in the traditional “open field” style that the British had mastered. The United States also could hope that Britain’s enemies (especially France) would be willing to help. At the very least, there were nations that would be willing to sell the United States weapons and send trained officers to advise and train the American Army. In time, these nations might also be willing to loan money or even join the United States in an alliance against Britain. The British enjoyed an overwhelming advantage over the United States in nearly every area. Britain’s Army and Navy were among the largest, best trained, most experienced, and well-equipped forces on the planet. The British had nearly ten times the population of the U.S. and Britain had many factories to make items for a war. In addition, Britain had 1000 times the wealth of the United States. Great Britain was confident that it could blockade the Colonies (after all, Britain refused to recognize that the United States was an independent nation) with its Navy while its Army took the “Colonials” apart piece by piece. Regardless of its strength and might, Britain did have weaknesses. Great Britain was an empire and it did have many colonies to defend all around the world. Simply put, Britain could not afford to use all of its strength to attack the United States. Army units and Navy fleets had to be scattered around the globe to defend the empire. Britain’s enemies would be ready to attack any weak spots and the British could not afford to let their guard down. Page 21 Another problem that faced Britain was the expense of fighting a war 3,000 miles from Europe. Everything that Britain planned to use in America had to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Britain had the ships to carry the goods, but the cost was enormous and Great Britain still had not fully recovered from the huge debt created by the French and Indian War. The British knew that it would be in their best interest to finish the war as quickly as possible. Britain’s greatest fear was that the rebellion in America would become a larger war like the French and Indian War. France was still a powerful nation in Europe and an alliance between France and United States could prove to be a financial and military nightmare for Britain. A war with France would mean that the alliance system of Europe would come into play and multiple nations would once again fight each other all over the globe. Great Britain, powerful as it was, could little afford to fight another world war. EFFECTS: Like the French during the French and Indian War, Britain needed to put an end to the war in America as quickly as possible. The longer the war dragged on, the greater the damage would be to the British Empire. The United States, on the other hand, needed to keep the war going long enough to win help from foreign nations. In reality, America’s only real chance of winning the war and remaining independent was to become an ally of a powerful European nation that could afford to send the United States weapons, money, soldiers, and a navy. “His Excellency” George Washington as Commander-In-Chief of the United States Army William Howe – first British Commander-In-Chief in the Revolutionary War Admiral Richard Howe Commander of British Naval forces in North America Page 22 Thomas Paine Author of “Common Sense” Thomas Jefferson Writer of the Declaration of Independence Benjamin Franklin America’s ambassador to France during the Revolutionary War Review Questions 1. After Thomas Paine published Common Sense, what did many Americans decide? 2. Why did John Adams want Thomas Jefferson to write the Declaration of Independence? 3. What made the Declaration of Independence one of the most important documents’ in World History? 4. During the Revolutionary War, Congress could only: 5. What was America’s only real chance of winning the war and remaining independent?