the Battle of Long Island

advertisement

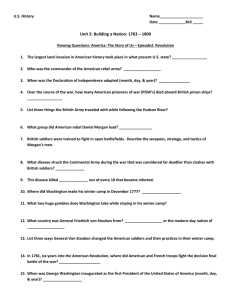

As George Washington had anticipated, British forces under General William Howe departed from Halifax, Nova Scotia in the late spring of 1776 and headed for New York City. The redcoats entered the harbor in late June and on July 2 established headquarters on Staten Island. Ten days later, Admiral Lord Richard Howe (William Howe’s brother) arrived with additional forces. Over a period of several weeks the British army grew to about 32,000 men, including more than 8,000 mercenaries hired for service in America. Washington had moved the Continental Army from Boston following the British evacuation. He realized that New York City would be difficult to defend, but its strategic and symbolic importance dictated that the effort be made. Fortifications were erected around the city, which was then confined to the southern tip of Manhattan, as well as on the Brooklyn Heights area of Long Island to the east of the city. The Americans were unsure of where the British would choose to strike first. Beginning on August 22, the British plan began to become clear. Soldiers were transported from Staten Island to Long Island by way of Gravesend Bay. Meanwhile, on the waters off New York City, Lord Howe exchanged fire with American batteries on Manhattan. Within a few days, 20,000 British soldiers congregated in the vicinity of the village of Flatbush. The American army of 10,000 was deployed in a series of fortified positions on Brooklyn Heights and spread across the surrounding Heights of Guan. Several skirmishes occurred between small bands of the opposing forces over the following days. On the night of August 26, British forces under General Howe were able to take advantage of intelligence provided by local Loyalists, who identified an undefended pass leading up to the Heights of Guan. Under the cover of darkness British soldiers managed to gain a position between American forces on Guan and the main force on Brooklyn Heights. In the daylight of the 27th the British opened fire on astonished Americans, who quickly recognized their dire situation. Continentals under John Sullivan of New Hampshire broke and ran. Fellow American commander William Alexander of Pennsylvania, fought effectively for a while, but was slowly encircled by numerically superior British forces. It was evident that disaster could be averted only by retreating down the hill and across the swamplands by Gowanus Creek. Such a move, however, would expose the Americans to deadly fire from the British in the hills above. To provide cover for the retreat, Alexander and Major Mordecai Gist led a band of 250 Marylanders on a direct assault against the British lines. The Americans broke under withering fire, but regrouped and bought sufficient time to allow the bulk of the army to flee, often throwing arms aside, to Brooklyn Heights. Only a handful of the Marylanders were able to escape. Alexander was eventually surrounded and he surrendered, and Sullivan was captured. The Americans listed about 1,400 casualties from the Battle of Long Island. The British toll numbered fewer than 400. This embarrassing display was observed by a helpless Washington from atop Brooklyn Heights. For the next two days, he and his army expected a British assault, an event that would most likely had led to a decisive British victory. During this period of quiet, the weather was unseasonably cold and a steady rain fell; American morale was at a low point and many soldiers talked of surrender. On the advice of his subordinates, Washington took advantage of British inaction and planned a retreat to Manhattan. British control of the harbor and rivers made this a risky prospect. Nevertheless, on the evening of August 29, the American army was ferried across the East River in a flotilla of small craft provided by sympathetic civilians. The retreat was aided immensely by calm waters that enabled the overloaded boats to make the crossing safely and by thick fog in the early hours of the next day that masked the departure of the last soldiers — which included a somber Washington. The question remains about why the British did not use their superiority on land and sea to strike a potentially lethal blow against the Patriot cause. Most historians agree that William Howe chose not to assault Brooklyn Heights because of his earlier experience at Bunker Hill where he also commanded an overwhelming force, but suffered extremely heavy losses. The general decided instead to set up a siege, believing that time was on his side. The failure of his brother, Admiral Howe, to halt the retreat across the East River has been ascribed to unfavorable winds that prevented his ships from destroying the tiny American flotilla and its human cargo. More recent historians, however, have argued that no ill wind was blowing at the time and that the admiral, a friend of America, was hoping to conclude affairs with a peace settlement, not a military victory to conclude the Battle of Long Island. The closing months of 1776 had been dire for George Washington and the Continental Army. Most recently, the losses of key forts had been followed by a hasty retreat across New Jersey with the British, led by Lord Cornwallis, in close pursuit. In early December, the Americans found temporary safety by crossing the Delaware River into Pennsylvania; those boats not used in the evacuation were destroyed, making it impossible for the British to follow until ice formed. Washington’s army had lost more than half of its men to illness, desertion and enlistment expirations. Faltering morale received a badly needed boost from Thomas Paine, who was serving as a volunteer aide; the stirring words of his pamphlet The Crisis were read to the soldiers on Washington's orders. As Christmas approached, a Loyalist butcher named John Honeyman was captured by American scouts in New Jersey and taken to Pennsylvania for an interview with Washington. In actuality, he was an American spy who conveyed the news to his comrades that Sir William Howe, the British commander, had called off Cornwallis’s pursuit and that their armies would take up winter quarters on Manhattan Island and Staten Island; several positions in New Jersey were to be manned by Hessian mercenaries. Honeyman was returned to Trenton, where he informed Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall that the Americans were completely demoralized and incapable of mounting an attack. Washington’s decision to strike against positions in New Jersey was motivated by two factors: a desire to instill confidence in his soldiers with a surprise attack and victory the fear of his army's continuing evaporation by large-scale enlistment expirations scheduled for the end of the year. On the evening of December 25, the American forces began to cross the Delaware in what was intended to be a three-pronged offensive. Weather conditions, however, did not make the passage easy. The heavily laden boats had to avoid ice floes in the river and a heavy snow storm turned to sleet. One segment of the offensive never departed from Pennsylvania and another succeeded in transporting its soldiers across the river, but not its artillery; those men returned to camp and did not participate in the battle. Washington had hoped to strike under the cover of darkness, but the difficulties encountered in the crossing delayed the attack until about 8 a.m. on the 26th. The American advance had been spotted earlier by a Tory, who delivered a written warning to British Colonel Rall. The colonel, however, was intent on celebrating Christmas and had stuffed the note in his pocket. Continental forces under Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan opened fire on the town and slowly surrounded it. A sleepy Rall mounted his horse and tried to rally his soldiers, but was shot and died later from his wounds. Within 90 minutes it was evident to the Hessians that they were outnumbered and escape routes had been cut off; they surrendered. The surprise victory at Trenton was important to the American cause for several reasons: For the first time, Washington’s forces had defeated a regular army in the field. American losses were extremely light; only two soldiers died and those apparently from exposure, not enemy fire. The Hessians sustained more than 100 casualties and 900 of their soldiers were captured. Several hundred Hessians escaped and presumably became American farmers and tradesmen. Further, Washington gained six cannon, 40 horses and a vast array of supplies that were quickly transported to Pennsylvania. Washington's command was solidified. A growing number of delegates to Congress had come to doubt his abilities, but those critics were quieted when news of the victory arrived in Baltimore. The victory sharply increased morale. New enlistments were stimulated and many of the current soldiers reenlisted. This turn of events enabled Washington to execute another daring move — the attack on Princeton on January 3. Brief thought was given to pursuing the fleeing Hessians, but continuing bad weather and the fact that American soldiers had discovered casks of rum ruled out that option. Name: ______________________________________________________________________ Due Date: Wednesday, 11-14 Please read the article on the Battle of Long Island and answer the following questions. 1. Where did the redcoats establish their headquarters in the vicinity of New York City? 2. Who was the British commander in New York, and how many men did he command? 3. Where did Washington and the Continental Army establish their headquarters? 4. Explain the British battle plan. 5. How were Howe and the British Army able to overtake the Continentals? 6. How were the Continentals able to escape a complete rout by the British? 7. What was the overall casualty rate for both sides at the Battle of Long Island? 8. Why did the British choose NOT to “strike a potentially lethal blow” on Washington and the Continental Army? Please read the article on the Battle of Trenton and answer the following questions. 9. What British commander was closely pursuing Washington and his army as they retreated across New Jersey into Pennsylvania? 10. How did Washington and his men prevent the British from following them across the Delaware River? 11. What document was written to attempt to boost the morale of Washington’s army? Who wrote it? 12. How was espionage used to help Washington mount an attack against the British? 13. Summarize the two reasons Washington decided to attack Trenton, NJ. 14. How did the weather impact Washington’s journey across the Delaware River? 15. Again, how did espionage play a role in the Battle of Trenton? How did the military commander deal with the reconnaissance he received? 16. Summarize the outcome of the Battle of Trenton. 17. Summarize the three impacts of the Battle on the American fight for independence.