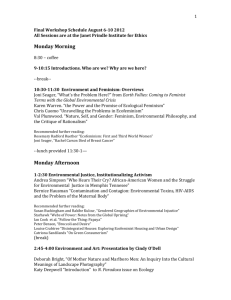

A Door Into Ocean Affirmative - Wave 1

advertisement