Essay 2 Death by Landscape

advertisement

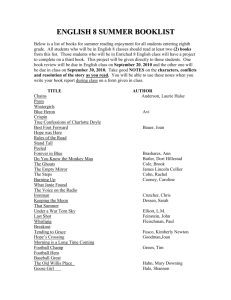

Patricia Nichtern March 31, 2011 Professor Zino Esaay 2 A Flatness that Stretches Deep into the Mind In “Death by Landscape”, the main character, Lois, uses landscape paintings to bridge the distance of time in her memory back to when she was in Camp Manitou. The sudden disappearance of her friend, Lucy, is constantly on her mind even as she grows older. They never found her body therefore Lois is not left with any closure and doesn’t even know, for sure, if she did in fact die. This causes Lois to be uneasy anywhere in the wilderness and even looking at a landscape painting reminds her of the place where she lost her friend. She has been consumed with a feeling of wonderment since the disappearance which profoundly affects her as an adult. The vastness of landscape, both in nature and in paintings, symbolizes the differences between Lois and Lucy which captivates each other creating a close bond. Lois’ uneasy enticement to the landscape paintings is a result of her feeling lost and helpless without her friend in the “convoluted tree trunks”, trying to sift through deep into them to find a resolution (Atwood 100). Interestingly, Lois keeps her distance from actual landscapes, which mirrors the distance she keeps from her family throughout her life. As a child, the literal distance between Lois and her parents shapes her character as she grows into an adult. Her parents first sent her there when she was very young, only the age of nine. The unfamiliar and vast landscape of the camp contrasting with the familiarity and safety that her home provided made her struggle with idea of the vast distance between the two. For her parents, sending their daughter away for the summer allowed them to be “removed from 1 the burdens” of parenting for a while (Tuan 122). Lois didn’t like many things about Camp Manitou, including the distance that was between her and her parents and her home. “She hated the necessity of having to write dutiful letters to her parents claiming she was having fun” (Atwood 103). Even though it was expected by her parents that she would enjoy being away at camp for the summer, at first she didn’t and “she could not complain” to her parents “because camp cost so much money” (Atwood 103). Lois assumed that her parents had sent her there because they thought it would be fun for her and because the idea that they were trying to alleviate the burden of her temporarily is not something a child wants to believe although it did occur to her. She “suspected her parents of having a better time when she wasn’t there” (Atwood 103). This distance between her parents also made her want distance, initially, between the other girls at the camp. She didn’t like being in such close quarters in a cabin with seven other girls; she wanted space from them as well. Lois is constantly struggling with the restrictions of space and the fear of too much space and distance. “Bottom bunks made hers feel closed in and she was afraid of falling out of top ones” (Atwood 103). This shows that Lois is uneasy with a space that should offer either coziness, in the bottom bunk, or a sense of freedom, in the top. There was a symbolic distance between the relationship of her and Lucy that foreshadows the literal distance she will have when she loses her friend. Lois and Lucy have many differences, but despite them and because of them they immediately create a very close bond. They are from different countries and backgrounds; Lois is from Canada and Lucy is from the United States. Lucy’s parents are very wealthy and are in a higher socioeconomic status. Lucy lived in a house in Chicago on a “lake shore and had gates to it, and grounds” (Atwood 2 104). The difference in socioeconomic status between the two girls is shown in their attitudes towards the camp. Lucy “would make the best of it, without letting Lois forget that this was what she was doing” while Lois knew that paying for the camp was a burden on her parents therefore didn’t complain when she initially didn’t like it (Atwood 104). Lucy had a confidence in her that Lois did not possess. “Lucy did not care about the things she didn’t know, whereas Lois did” (Atwood 105). Lois enjoyed teaching Lucy all of the things that she had learned at camp over the years; it gave her a sense of confidence with a friend that she felt inferior to. Every summer, Lucy had something to boast about from her year spent away from Lois. In comparison, Lois’ life seemed boring and ordinary and this made Lois feel even more distant from Lucy but still intrigued by her life and stories. The two girls had overcome their differences and relied upon each based on their strengths and weaknesses. When they went on the canoe trip, Lois was uneasy with the distance from the camp and the vulnerability of being in middle of the water. She felt “the water stretching out, with the shores twisting away on either side, immense and a little frightening” (Atwood 107). When Lois and Lucy stop at Lookout Point and climb up to the summit, far away from everyone else, Lois sees the “sheer drop to the lake and a long view over the water” revealing how far away they’ve come (Atwood 111). This distance down to the lake symbolizes the distance between Lois and Lucy and the apparent differences in their characters. Lucy is daring, confident and unafraid and she steps close to the summit to see the drop closer. Lois, on the other hand, “gets a stab in her midriff” when she sees how close to the edge Lucy is, showing that she is afraid ; afraid that her daring friend might jump or fall (Atwood 112). When Lois tries to remember the “shout”, the last thing she ever heard out of Lucy she cannot be totally positive 3 how to interpret it (Atwood 112). Lois, nor anyone else, ever finds out what happened to Lucy. Everyone else assumes she is dead but Lois never gets closure and believes Lucy “is nowhere definite, she could be anywhere” (Atwood 117). This idea consumes Lois ever since that day and she is haunted by the fact that her friend was never found. The uneasiness of the literal distance between them now is overwhelming to her and she cannot escape it. “The greater the distance the greater the lapse of time, and the less certain one can be of what has happened out there” (Tuan 121). Lois lives in the “borderland between the objective and the subjective realms” (Tuan 121). The landscape paintings are the “mythical space and time” in which Lois spends trying to find and reunite with her friend. This “borderland” is the subjective realm which “signifies the…’inner’ aspect of (her) experience” at Camp Manitou which adversely affects Lois throughout her life (Tuan 120-121). Ironically, Lois can remember most of days at the camp but it is difficult for her now to remember “having her two boys in the hospital, nursing them as babies”, “getting married, or what” her husband “looked like” (Atwood 117). She was consumed with the idea that Lucy was still out there somewhere; in the woods by the lake or somewhere in the vastness of a landscape. She “never felt she was paying full attention” to her family (Atwood 117). She distanced herself from them, just as her parents did to her. She also distanced herself from “any place with wild lakes and wild trees” because of the uneasiness that the landscapes made her feel. This objective “reality is the historical physical universe”, but for Lois there is no certainty in what happened to Lucy therefore she was torn between the objective and subjective reality, constantly drifting between both (Tuan 120). Her subjective reality is that Lois is still out there somewhere and “lies in the realm of expectancy and of 4 desire” (Tuan 120). The distance between Lois and Lucy is part of Lois’ objective reality but with “limits… (that) stretches away from (her) to the remote distance…at which details cease to be knowable” (Tuan 121). Lois feels as if she lies somewhere within the landscape paintings that she surrounds herself with. When Lois looks deep within them she can “see time ‘flowing’ through space” (Tuan 124). Looking into them is her “backward glance” she has “already trodden” and by doing so the “past and the future can be evoked by the distant scene” (Tuan 124). This backward glance both into the past and into the future fills Lois with the uneasy realization that “as far back you go (into the painting), there will be more” and that she will never come to any sort of closure as to the whereabouts of her friend (Atwood 118). In the landscapes paintings Lois sees another world; a world which Lucy is still a part. Through the landscape paintings, Lois is “living not one life but two”; reality and her subjective reality (Atwood 117). Lois does not just see a flat surface in the paintings but a “larger totality” and the distance that is represented in them (Casey 263). Lois does not visualize any sort of background in these landscapes; “only a great deal of foreground that goes back and back, endlessly” (Atwood 118). Lois “projects” herself and Lucy “onto the landscape” every time she looks into the paintings and imagines that Lucy is behind one of the farthest trees depicted in the landscape, somewhere in them “she’s there” (Casey 261) (Atwood 118). They represent for Lois an “opening up and opening out of a scene, a panoramic sense of unending space (and …also time)” (Casey 265). 5 Arthur Lismer, Sunlight in a Wood (detail), 1930 This landscape painting represents the type of painting that Lois can see Lucy in. There is no background in this painting and the depth that is portrayed by the artist conveys a sense of vast distance in which the viewer is never able to cover completely. Lois imagines that Lucy is somewhere in there, not behind the “convoluted tree trunks” that are in the foreground of the painting, but far back in distance and in time, behind a tree that is not quite visible. Lismer’s painting correlates with Lois’ feeling about the Camp Manitou and the lake; “immense and a little frightening” (Atwood 107). This painting does not give the viewer a sense of calmness that some landscape paintings do, but rather a more confused feeling as if you can easily get lost in those woods or trapped under the tree trunks. It forces your eyes to jump all over the canvas “scoping out…the limits of a perceptual scene” while never being able to find it (Casey 264). 6 Works Cited Atwood, Margaret. Death by Landscape. New York: Doubleday, 1991. Casey, Edward S. Rethinking Nature: Essays in Enviornmental Philosophy. Eds. Bruce V. Foltz and Robert Frodeman. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2004. Lismer, Arthur. Sunlight in a Wood. 1930. Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario. AGO: Art Gallery of Ontario. Web. 3 Apr. 2011. Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnisota Press, 1977. 7