Chapter 18

Pricing Policies

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Main Topics

Price discrimination: pricing to extract

surplus

Perfect price discrimination

Price discrimination based on observable

customer characteristics

Price discrimination base on selfselection

18-2

Price Discrimination: Pricing to

Extract Surplus

Monopolist’s profit would be larger if he could solve two

problems

Consumers who buy some of the product receive some

consumer surplus

Monopolist could increase profit if he could charge them a

higher price

Consumers aren’t buying some units that they value

less than the monopoly price but more than marginal

cost

Monopolist could increase profit if he could charge these

buyers less for those units of the good

Monopolist might be able to do better by price

discriminating: charging different prices for different

units of the same good

18-3

Price Discrimination: Pricing to

Extract Surplus

To be able to price discriminate:

A firm must have some market power

If not, a price above marginal cost will result in zero sales

The good or service must be difficult to resell

Otherwise few sales will occur at the higher price

Firm must also be able to distinguish sales for which the

purchasers have a high willingness to pay from those they

have a low willingness to pay

A monopolist can perfectly price discriminate if he

knows perfectly the customer’s willingness to pay for

each unit he sells and can charge a different price for

each unit

18-4

Price Discrimination: Pricing to

Extract Surplus

Usually, a firm does not perfectly know a customer’s

willingness to pay

Two different ways to distinguish purchases for which

the customer has a high vs. a low willingness to pay

Price discrimination is based on observable customer

characteristics when a firm can distinguish

consumers with a high vs. low willingness to pay

Price discrimination is based on self-selection when

the firm offers a menu of alternatives

Designed so that customers will make choices based on their

willingness to pay

In quantity-dependent pricing, the price a consumer

pays for an additional unit depends on how many units

she has bought

18-5

Perfect Price Discrimination

Under perfect price discrimination, the firm knows

perfectly its customers’ willingness to pay

Can set the price for each individual consumer equal to

her willingness to pay

Marginal revenue curve coincides with the market

demand curve

Profit-maximizing sales quantity occurs where the

market demand curve crosses the marginal cost curve

Monopolist produces the same quantity as would occur

in a competitive industry

Each consumer consumes the same quantity as they would

under perfect competition

No deadweight loss

18-6

Figure 18.2: Perfect Price

Discrimination Sales Quantity

18-7

Two-Part Tariffs

Two-part tariffs are another quantity-dependent pricing

plan that allows a perfectly discriminating monopolist to

maximize profit

With a two-part tariff, consumers pay a fixed fee plus

a separate per-unit price for each unit they buy

Examples: amusement parks, rental car companies

Commonly used by monopolists and firms whose

market power falls short of monopoly

Advantage is simplicity: name just two prices

To maximize profit, set per-unit charge equal to

marginal cost

18-8

Figure 18.4: Profit with a

Two-Part Tariff

Per-unit charge equals

marginal cost

Fixed fee is the

consumer’s surplus at

that per-unit price

Maximizes aggregate

surplus

Leaves the consumer no

surplus

18-9

Sample Problem 1 (18.2):

If the ice cream company from figure 18.2 (page

669) sells to Juan (whose demand curve is

shown on page 524) using a two-part tariff with a

per-cone price on $1.50, what is the largest fixed

fee it can charge Juan and still persuade Juan to

make a purchase? How does its total revenue

from Juan under this two-part tariff compare to its

total revenue from Juan when it sells Juan four

cones, each priced at Juan’s willingness to pay

for it? What is its total profit from Juan?

Price Discrimination Based on

Observable Characteristics

Most often a firm’s ability to price discriminate is

imperfect

May be able to sort consumers into rough groups

based on observable characteristics

But know no more about their willingness to pay

Cannot engage in quantity-dependent pricing because cannot

track purchases

Example: small town movie theater with four consumer groups

(adults, seniors, students, kids)

To maximize profit consider each group’s demand

curve separately

Set price to maximize profit earned from that group

18-11

Price Discrimination Based on

Observable Characteristics

Set different prices whenever the groups have different

elasticities of demand

Charge a higher price to groups with less elastic

demand

Generally the group that will face the higher price is the

one with the less elastic demand at the profitmaximizing no-discrimination price

Starting at that price, monopolist will:

Raise the price of the less elastic group

Lower the price of the more elastic group

Can find optimal prices and quantities for each group

using algebra

18-12

Figure 18.5:Profit-Maximizing

Price to Two Groups

18-13

Sample Problem 2 (18.4)

Suppose moviegoer’s demand functions are

QS = 800 – 100P and QA = 1600 – 100P for

students and other adults respectively.

Marginal cost is $3 per ticket. What prices

will the monopolist set when she can

discriminate and when she cannot? How

will discrimination affect her profit?

Welfare Effects of Imperfect

Price Discrimination

Profit is at least as large with discrimination as without

Can always charge every group the same price, won’t charge

different prices unless it benefits the firm

Price discrimination affects different groups of consumers

differently

Worse off it my price rises as a result of discrimination, better off if it

falls

Two main effects on consumer and aggregate surplus:

Different consumers pay different prices, inefficient because a

consumer who faces a low price and decides to buy may have a

lower willingness to pay than a consumer who faces a high price and

decides not to buy

May encourage the monopolist to sell more, increase both consumer

and aggregate surplus

Opposing effects can combine to either raise or lower consumer

and aggregate surplus

18-15

Welfare Effects of Imperfect

Price Discrimination

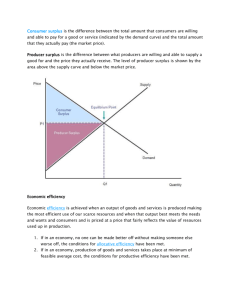

In Figure 18.7, total consumer surplus is

smaller with discrimination

The gain to college students is smaller than the loss

to other adults

Aggregate surplus is also smaller with

discrimination

Gain in profit ($800) is smaller than the loss in

consumer surplus ($1,200)

The number of tickets sold is the same

But inefficiently distributed with discrimination

18-16

Figure 18.7: Welfare Effects of

Price Discrimination

18-17

Sample Problem 3 (18.8)

What is the effect of discrimination on

consumer and aggregate surplus in

exercise 18.4?

Price Discrimination and

Market Power

In a competitive market, firms can’t price

discriminate

Price discrimination is a sign of a market that is not

perfectly competitive

Can be difficult to determine whether price

discrimination exists in a market

Different prices may reflect cost differences

Market does not have to be very far from

perfectly competitive to exhibit discrimination

Oligopolists may price discriminate more than

monopolists

18-19

Price Discrimination Based on

Self-Selection

Often firms cannot distinguish between groups

of consumers based on observable

characteristics

Price discrimination may still be possible

Offer a menu of alternatives

If properly designed, customers with different

willingness to pay will choose different alternatives

A common practice

Examples: supermarket discounts for shoppers who

clip coupons, wireless phone companies with

multiple calling plans

18-20

Quantity-Dependent Pricing and

Self-Selection

Recall that a perfectly discriminating monopolist

maximizes profit with a two-part tariff

This level of profit is not achievable when consumers’

characteristics are not directly observable

If given the choice between two plans with the same

per-minute price, all consumers will opt for the lowdemand (low fixed fee) plan

Consumers will not self-select based on willingness to pay

The monopolist can often do better by raising the perunit charge above its marginal cost

Can do even better by offering a menu of different twopart tariffs

18-21

Figure 18.9: Two-Part Tariff with

Two Types of Consumers

18-22

Clearvoice Wireless Example

Clearvoice is a wireless telephone monopolist in a rural

area

Two types of consumers, high-demand and lowdemand

Distinct monthly demand curves for wireless minutes for each

group

Clearvoice’s marginal cost is 10 cents

If could observe consumer characteristics, would offer

two-part tariff with 10-cent per-minute price

Fixed fee for low-demand customers: $8

Fixed fee for high-demand customers: $40.50

18-23

Profit-Maximizing Two-Part Tariff

Suppose Clearvoice wants to offer a single two-part

tariff

Per-minute price of 10 cents and monthly fee of $40.50

High-demand customers accept

Low-demand customers reject

Per-minute price of 10 cents and monthly fee of $8

All consumer accept

Which plan is better?

If there are a large number of low-demand customers, $8

monthly fee is better

May be even more profitable to raise per-minute fee

above marginal cost

18-24

Profit-Maximizing Two-Part Tariff

If the monopolist plans on selling to both types of

consumer it is always profitable to raise the per-unit

price at least a little above marginal cost

Regardless of the types’ relative proportions

Would like to extract some of high-demand consumers’

surplus without changing surplus of low-demand

consumer (already zero)

Raise per-unit price to get more surplus from high-demand

consumers

Adjust fixed fee so low-demand consumers’ surplus is

unchanged

The smaller the faction of low-demand consumer, the

more worthwhile it is to raise the per-unit price

Deadweight loss from low-demand consumers increases

18-25

Figure 18.10: Benefits of Raising

the Per-Minute Charge

18-26

Using Menus to Increase Profit

Can do even better by offering a menu of twopart tariffs, each designed to attract a specific

type of consumer

Can eliminate some deadweight loss by introducing

a second tariff plan

Extract more surplus from high-demand consumers

by making the low-demand plan less attractive to

high-demand customers

18-27

Eliminating Deadweight Loss of

High-Demand Consumers

Suppose Clearvoice offers a pair of two-part tariffs

One designed for low-demand consumers:

Per-minute price of 20 cents, fixed fee of $4.50

Second option intended to attract high-demand

customers:

Per-minute price of 10 cents, equal to Clearvoice’s marginal

cost

Fixed fee should be set as high as possible without causing

high-demand consumer to choose the other plan

With menu of plans:

Firm profits are higher from high-demand consumers

Profits from low-demand consumers are the same

Deadweight loss from high-demand consumers is eliminated

and extracted as surplus

18-28

Figure 18.11: Menu of

Two-Part Tariffs

18-29

Making the Low-Demand Plan

Less Attractive

Can increase profit even more by making the lowdemand plan less attractive to high-demand

consumers

That plan determines the fixed fee the firm can charge a highdemand consumer

It is the level that makes the high-demand consumer indifferent

between the two plans

Limit the number of minutes a consumer can purchase

in the 20-cent-per-minute plan

Set the limit equal to the number low-demand consumers want

Will have no effect on value a low-demand consumer derives

Make the plan less attractive to high-demand customers

Will increase the fixed fee Clearvoice can charge high-demand

consumers for the 10-cent-per-minute plan

18-30

Figure 18.12: Capping Minutes

18-31

Menu of Two-Part Tariffs

A firm can often profit by offering a menu of

choices

Designed for different types of consumers

To maximize its profits, firm should try to make

each plan attractive to one group only

And unattractive to other consumer groups

Firm benefits from setting the per-unit price in

the plan intended for consumers with the

highest willingness to pay equal to the marginal

cost

Eliminates deadweight loss for those consumers

18-32

Sample Problem 4 (18.12):

Air Shangrila sells to both tourist and business

travelers on its single route. Tourists always stay

over on Saturday nights, while business travelers

never do. The weekly demand function of tourists

is QT = 6,000 – 10P, and the weekly demand

function of business travelers is QB = 1,000 – P. If

the marginal cost of a ticket is $200, what prices

should Air Shangrila set for its tourist and

business tickets? If the government passes a law

that says all tickets must cost the same, what

price will Air Shangrila set?