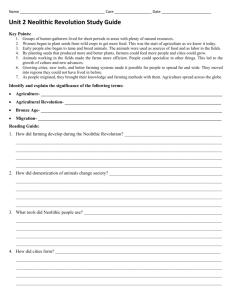

The Neolithic Revolution?

2. THE NEOLITHIC REVOLUTION?

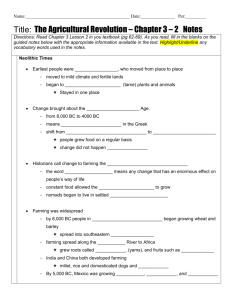

Today, most of our food comes from plants and animals that humans have done a great deal to produce and alter. This is farming, or agriculture , broadly construed. It involves both cultivation (growing plants and raising animals) and domestication (altering other species, whether plant or animal, through selective breeding). Most often, moreover, domestication has been done with specific goals in mind, such as making the edible portion of a grain plumper, adapting a crop to a new environment, or making livestock yield more milk —while also producing unintended effects.

An important feature of the established understanding of farming is that it appeared only after—indeed, long after—the emergence of Homo sapiens as a species. While no one claims to know precisely when farming began, the broad consensus is that this occurred around 12,000 BP

(or 10,000 BCE). It is this onset of farming, located roughly at this time, that the Neolithic

Revolution names.

The onset of farming is deemed “revolutionary” for two reasons. First, because farming is understood to be radically different from—indeed, the opposite of—what preceded it, most specifically in terms of humanity’s relationship to its sustenance. On this established view, during the long Paleolithic Era that preceded farming (in other words, throughout human existence until roughly 12,000 BP), humans had obtained their sustenance solely from what nature itself provided. These earlier humans hunted animals and gathered (or foraged for) plants, but they engaged in neither cultivation nor domestication: all that they ate—as well as the skins and furs that protected them from the elements—depended on whatever nature alone supplied.

Importantly, this gave Paleolithic humans no choice but to be nomadic : without farming, the

1

sustenance available in a given area did not allow even small communities to stay put yearround. Paleolithic humans thus had less control in relation to nature and their own survival— indeed, no more than other animals. The earliest farming was thus an “invention”: the formulation of something entirely novel.

The second reason the emergence of farming is deemed “revolutionary” involves the understanding of its consequences. On the established view, the onset of farming involved, from the get-go, a shift to sedentarism : remaining in one place to harvest crops that had previously been cared for and planted. Unlike hunting-and-gathering, it yielded food surpluses, rather than mere subsistence. Over time, involving several centuries and millennia, these surpluses led to a fantastic and interlocking cluster of changes. To name just the most prominent: the surpluses supported non-laboring elites , state-formation , urbanization , and occupational specialization.

Specialization in turn, facilitated numerous important inventions, including writing, while the combination of surpluses and specialization resulted in a dramatic expansion of trade. Taken together, this bundle of changes has often been spoken of as the beginnings of civilization .

Because this designation suggests that hunting-gathering societies are un-civilized and inferior, many scholars and textbooks—particularly recent ones—have become uncomfortable with it, and instead speak of the emergence of complex societies . This alternative phrasing sounds less judgmental, but it too figures farming as an advance over an earlier, simpler—that is, a more primitive

—way of life.

These ideas about the Neolithic Revolution embrace a notable decision about the significance of different historical timescales. They treat Neolithic farming as the root cause of long-run human betterment—and make this the main thing we should know about it—even though, as we will see, most evidence indicates that for many, many centuries after the onset of

2

farming, there was no general rise in human material welfare. (Indeed, by many measures, life got worse for most early farmers.) Put otherwise, the established Neolithic Revolution model tells us that early farming’s real significance is the opposite of what many generations of human beings experienced following the onset of farming.

The Geography of the Neolithic Revolution

The received notion of the Neolithic Revolution has another feature worth highlighting.

Just as this “revolution” has been located at a particular moment, it has also been consistently identified with a particular place: the Fertile Crescent (Map 2.##).

Even when scholars were first formulating the Neolithic Revolution idea (in the early decades of the 1900s), they knew that humans in China and the Americas had also invented agriculture, independently of the Fertile Crescent. Yet in developing the Neolithic Revolution model, they relied almost exclusively on—and disproportionately pursued further research into—early farming in the Fertile Crescent. Indeed, they often treated the transition to farming as synonymous with this particular transition to farming.

The Fertile Crescent became the privileged case because it had been Europe’s source of both farming and farming’s “civilizational bundle.” Given the then-accepted view that Europe was the dominant actor in human history, being Europe’s source meant that the Fertile Crescent influenced human history more than any other site of early farming. Essentially the same point has sometimes been expressed in “civilizational” terms: since Europe was the principal site of civilizational progress, being Europe’s source made the Fertile Crescent the most important— and even, the singular—site of “the birth of civilization.”

Note here that to treat early farming in the Fertile Crescent as uniquely significant because farming spread from there to Europe, which subsequently became disproportionately

3

influential in the world, is to provide a rationale for commemoration: it is a claim that it is this case of early farming that is most worth remembering. Yet, however valid (or not) such a claim might be as a brief for commemoration, it is a poor basis for generalizations and social scientific investigation. Clearly, we cannot reliably identify the full range of early farming’s consequences if we privilege one particular example based on its supposedly unique consequences. Historians need, then, to distinguish between commemoration and analysis. Each may have its place, but they are different—and focusing on the first typically short-circuits the second.

A second problem is that this approach presumes that Europe (and its sources) are the proper place to look in order to study “civilizational advancement.” In fact, the measurable features of what is called “civilization”—sedentarism, urbanization, state-formation, trade, occupational specialization, and so on—have neither been distinctive to, nor most fully developed in, Europe, except at a few selected moments. Europe’s past and antecedents are thus too narrow a basis for understanding the development of these “civilizational” traits. Here too, then, a broad inquiry into the different cases of early farming and their consequences is superior to focusing on any one case.

Finally, it is crucial to note that more recent research has identified roughly a dozen independent sites of early farming, with more possible (Map 2.##). This profusion of cases only strengthens the argument against treating the shift to farming as singular and the Fertile Crescent as its essence.

Reflections on the Logic of the Neolithic Revolution

Beyond reviewing the existing evidence about the emergence and consequences of farming across its many sites, this chapter asks, Is “the Neolithic Revolution” what happened?

4

Put more fully: How well does the received model fit the evidence? Do any alternative approaches fit better?

Before examining the evidence, it is important to further outline some key aspects of the

Neolithic Revolution model. First, let us note that in each of the two ways that the shift to farming is regarded as “revolutionary” within the received model, we find a distinctly social evolutionary understanding of humanity’s movement through time (Chapter 1). With the onset of farming, apart from its direct consequences, there is the transition from an animal-like way-oflife to a distinctly human way-of-life; and with the consequences or outcomes of farming, there is the additional transition to a more complex form of society, defined, moreover, by the bundle of traits conventionally placed under the label, “civilization.”

This observation gives us the most basic question that must be asked in regard to whether the Neolithic Revolution happened: Did the shift to farming constitute a social evolutionary advance, from a primitive to a higher form of human existence?

This also gives us some sense of why it is important to ask how well the Neolithic Revolution model fits the evidence, since this observation shows us that the model carries and conveys a vision of the overall shape of human history.

It should be obvious that to ask if the shift to farming was a social evolutionary advance requires that we gauge whether farming gave rise to “progress” —and this question will indeed be central to the final section of this chapter. What is less obvious is that this also requires us to examine the character of human existence before farming. Here, what is crucial is that within the

Neolithic Revolution model, farming is more than an observable set of specific practices, such as planting, harvesting, herding, selective breeding, and so on. Instead, farming—in the established model—is nothing less than the first instance of human beings acting, with intentionality, to

5

augment and shape their sustenance—or more broadly, to control nature. Were there evidence that humans, prior to farming, deliberately manipulated nature in other ways, then farming would not have the transcendent significance the Neolithic Revolution model gives it. The multiple inventions and diffusions of Neolithic farming would still be hugely important historical events, but they would no longer represent the crossing of a developmental threshold, from an animallike to a distinctly human way of life.

Here, the most fundamental question is which is more plausible: that acting to augment and shape sustenance originated in a moment of extraordinary invention, long after the emergence of Homo sapiens , or that acting in this way is a constitutive element of humanness and thus a general propensity of humans (Chapter 1). Evidence of Paleolithic efforts to shape sustenance thus becomes critical; and the large number of independent cases of early farming is also telling: were there no general human propensity to act in this way, would not such an invention be rare, rather than so plural?

One further implication of the social evolutionary logic of the Neolithic Revolution model deserves attention: note that it suggests that any and all groups that sustain themselves through hunting-and-gathering, whenever they actually live, are living as if they belonged to the pre-farming Paleolithic. This is what is meant when such persons, even if they are our contemporaries, are identified as “primitives.” The general lesson here is that if human existence over time is understood to involve a sequence of social evolutionary or developmental stages, then the stages will serve to classify human differences, even among people existing at the same time. This is yet another reason why it is important to assess whether the Neolithic Revolution is what happened: the claim that it did contributes to, and even anchors, a potent way of seeing and ranking ourselves and other human beings.

6

We turn now to the time before farming, the Paleolithic. We wait, however, until the subsequent discussion of early farming to focus on Paleolithic strategies for obtaining sustenance, in order to compare the two directly. We turn first to other aspects of the Paleolithic to provide a different and independent basis for assessing the plausibility of the vision of the

Paleolithic as devoid of human efforts to control nature—as the zero point of human social evolution, in effect.

7

Before 12,000 BP

Our evidence about human beings prior to 12,000 BP is spotty, and extremely so for before 40,000 BP—which is roughly the earliest time from which we have works of art, indicating, with little controversy, the presence of creators who were fully human (Figures 2.## and 2.##).

For any earlier time however, one great uncertainty is just when in the past fully human beings were present. Our primary evidence about these distant ancestors consists of fossilized skeletal remains, plus some stone tools. Based on the form of the skeletal remains, along with analysis of DNA recovered from them, scientists who study such things have generally concluded that our own species— Homo sapiens —came to exist around 100,000 BP and probably a bit before. These earliest Homo sapiens lived, it is widely agreed, in sub-Saharan

Africa, largely in areas of savannah (or grasslands), and numbered in the tens of thousands

(Map 2.##). We have no direct evidence, however, regarding whether these ancestors were behaviorally fully human. Particularly important, we have no traces of any language use by these ancestors—and we probably never will, given that speech is ephemeral.

How, then, do we interpret the lack of evidence for language and much else at this time?

What do we make of having found no artworks from before 40,000 BP? Or not having any evidence of fixed settlements prior to 25,000 BP? It is common to speak of the earliest archaeological finding of something as indicating when, roughly, it first occurred; for many phenomena, however, this is probably mistaken. Earlier cases—even much earlier cases—might have existed without our knowledge, either because no evidence of them has survived or because we have not yet found it. Indeed, this latter possibility keeps turning out to be the case, so that

8

dates for the first appearance of many things in early human history have repeatedly been pushed back in time with new archaeological findings (Figure 2.##).

In regard to language in particular, a suggestive argument is that one of the most unique things about Homo sapiens is how much we depend—even when carrying out such basic biological activities as eating—on knowledge that is produced collectively and transmitted through socialization. Note, for instance, that humans have no instinctual knowledge of which plants and animals are safe—much less good—to eat, while such instincts are commonplace among other animals. And given the complexity of communication needed to both obtain and share such knowledge, it becomes difficult to see how humans could possess it without possessing and using language. On this argument, then, it seems plausible, even probable, that our ancestors of 100,000 BP possessed language—assuming the identification of them as Homo sapiens is correct. To put this somewhat differently: it is difficult to imagine that the oft-noted biological incompleteness of Homo sapiens (Chapter 1) could have preceded language, at least by much.

That our ancestors from 100,000 BP or not much later possessed language is further supported by one of the few things we know about them with much certainty—which is that from that time forward, they moved outward from Africa and dispersed to all corners of the earth, and did so with striking rapidity. Indeed, prior to the onset of farming, human beings that are identified—by DNA analysis—as direct descendants of the first Homo sapiens in Africa were well established on every continent (except Antarctica), as well as on many islands, particularly in the Pacific (Map 2.##). This means, moreover, that Paleolithic humans had moved into habitats radically different from African savannahs—and from each other. Some destinations were forested and thus required sharply different skills for obtaining sustenance. Many of them

9

were dramatically colder, particularly since the migration from Africa occurred during an extended Ice Age; they thus presented humans with novel needs for suitable shelter and clothing.

Other destinations were largely desert; still others, coastal areas. Just which plants and animals in these diverse habitats were edible varied enormously, as did their availability in different places and seasons; techniques to hunt or capture diverse animals in diverse habitats had to be developed and explained to others. Inhabitants of the vast frozen tundra of Eurasia, for instance, relied heavily on hunting very large, fat-laden mammals, such as mammoths, while humans who had settled on islands and some coastal areas relied heavily on seafood—in both cases, diverging greatly from the diets available on African savannahs. The relative rapidity with which humans learned to live in these diverse locales thus indicates a singular capacity to produce and transmit local knowledge (meaning, knowledge that they could not have brought with them ); this, again, seems difficult to imagine without language. At the very least, the adaptability that these humans displayed through migration places the burden of proof on those who claim these humans lacked language.

Though we know that humans were almost everywhere on earth by 12,000 BP, we are much less sure when they arrived in each area. Based on currently available evidence, we can say that humans had settled in what is today the Middle East soon after 100,000 BP, though the population there may have departed or died out after some twenty-thousand years. Humans probably reached East Asia some 80,000-67,000 years ago, and a second wave of migrants reached the Middle East around 60,000 BP. Australia was reached around 50,000 BP; Europe— according to current research —no earlier than 45,000 BP, and the Americas (by way of Asia), around 15,000 BP, though there is reason to suspect some previous entry into the Americas.

Some of this dispersion—notably to Australia and nearby New Guinea (by 40,000 BP)—

10

required seaworthy vessels and impressive knowledge regarding how to travel in them over substantial distances.

Living in a world with airplanes, we might think that the tens of thousands of years it took Homo sapiens to disperse from Africa to all corners of the world was slow. But a more appropriate comparison suggests that this dispersal occurred with striking rapidity, demonstrating a singular—which is to say, a distinctly human—capacity for producing and transmitting knowledge. An earlier species of our own genus, Homo erectus, had also migrated out of Africa, beginning about 1.75 million years ago. But its migration took some 500,000 years and was confined to southern Eurasia (Map 2.##): it thus took six times as long and did not reach nearly as far, indicating far weaker capacities for migration and adaptation than is evidenced by Homo sapiens . The difference seems even more striking if we consider that Homo erectus itself made stone tools. Yet, what is striking about its tools, and consistent with its more limited migration history, is how homogenous the tools are, both over time and across its full geographic, and thus environmental, range (Figure 2.##). In an important sense, what is simple here is less the properties of any individual tool than the lack of variation and change across the set of them. Tools made by Homo sapiens, on the other hand, varied widely , even during the

Paleolithic (Figure 2.##).

The global dispersal of Homo sapiens may offer us one final lesson, which would again indicate how distinctively human its migrations were. Most scholars have sought to explain migration outward from Africa and beyond in functionalist terms, meaning that they have tried to show that migration was a response to practical problems or needs (Chapter 1). This seems to be why other species migrate: so, for example, animals move because of over-crowding, the decline in a crucial resource, or a sudden unfavorable change in environmental conditions. Yet

11

functionalist explanations of human migration have made very little headway. This may, of course, turn out to be solely because we lack sufficient evidence. But if, as new evidence accumulates, scholars still cannot offer persuasive functionalist accounts of this phenomenon, it would not mean that humans dispersed to all corners of the earth for no reason at all. The more plausible alternative hypothesis would be that our ancestors left their homes and relocated for purposes of their own devising—which is to say, for cultural reasons (Chapter1).

Such an alternative theory would not imply that humans have some natural impulse, or instinct, to wander and explore. After all, each time some humans migrated to new areas, others stayed put. Thus, neither wanderers nor home-bodies should be privileged as manifestations of human nature. What we wish to suggest instead is the possibility that humans at different moments formulated projects and goals that led some of them to undertake daunting migrations, upending their known worlds—without being driven by sheer necessity.

A final point to note here is that over the tens of thousands of years in which Homo sapiens spread across the planet, the human population consistently grew. By the time given for the Neolithic Revolution, there were some five to ten million humans by the best estimates, rather than merely tens or even hundreds of thousands.

Extraordinary Cultural Products

Amidst the uncertainties about human histories in the Paleolithic, it is clear that at least from 40,000 BP forward, some of our ancestors produced creative works that are distinctly human products, in terms of their richness, complexity, and variability. One group of these—an example of which we presented earlier (Figure 2.##)—are known as the Venus Figurines.

These are small statues of women (never men), in most cases entirely nude, which have been found widely across Europe and as far east as Siberia. So far, more than 100 have been

12

recovered, with the earliest dated to 39,000 BP and the majority between 30,000 and 20,000 BP; it seems reasonable to assume, moreover, that many more such figurines were produced within that time span, given the odds against us finding and recognizing any given object from so long ago. Some of those that have been recovered are carvings, whether in bone, stone, or mammoth ivory, while others are ceramic or fired clay; there are also noticeable stylistic differences amongst them (Figure 2.##). What most of them share, however, is the prominence of the vulva, breasts, and buttocks. Since their first discovery in the late 1800s, it has often been assumed that they were “fertility symbols.” This suggests, in effect, that they represented an effort to promote pregnancy and births through “magic”— and were thus a primitive and irrational means to achieve a practical end. But as the filmmaker Werner Herzog has wryly noted, in his 2010 documentary, “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” it seems just as possible that they were erotic objects, designed to stimulate desires, rather than to manipulate external, non-human, forces. We should, however, be cautious about fitting the figures into any of our own notions or familiar categories. So too, we should remember that while from our vantage point the 100-plus figures seem to be examples of a single type, they were in fact made thousands of miles apart over a span of roughly 20,000 years—which is ten times the length of time during which people have made Christian crucifixes, for instance. We thus should wonder in what ways those who made the figures may or may not have had connections with other producers —whether predecessors, contemporaries, or successors—and about the possibility that these objects meant many different things in the different communities where they were made and kept.

Because the Venus figurines typically exhibit considerable wear, it is difficult to fully assess the artistic skill behind them. By contrast, a small number of paintings from 40,000-

30,000 BP are much better, though still imperfectly, preserved: they were made in the protected

13

depths of caves, and gained further protection when geological processes sealed the caves for thousands of years, until they were discovered in recent decades. The paintings in the Chauvet

Cave in France, discovered in 1994, are extraordinary examples (Figures 2.## and 2.##). An important element of these paintings that these photographs cannot show is that they were composed as three-dimensional works, using the shapes of rocks to help depict the shapes of the painted animals. (Herzog’s film, shot in 3D, captures this powerfully.) To our eyes, these paintings show a sophistication that argues against treating them as “primitive” works, representing the earliest steps on a long path of development that leads to the paintings of

“civilization” or “modern art” (Figures 2.## and 2.##). The Chauvet paintings are, instead, fully rendered works in their own right—ones that bespeak skills built up and shared over many generations.

Many Species?

As we noted in Chapter 1, there is no question about the biological unity of humanity today: we are a single species. In the period we have been discussing, by contrast, there is evidence that various groups of Homo sapiens did encounter other species of the genus Homo .

Perhaps the clearest of these cases involves Homo neanderthalensis , or Neanderthals , whose remains have been found widely in Europe, and who seem not to have gone extinct any earlier than roughly 40,000 BP. Before we could analyze DNA from skeletal remains, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were identified as two clearly distinct species, based on differences in the forms of the skeletal remains. DNA analysis has complicated and even confused this picture, however. Some studies have reported evidence of interbreeding between sapiens and neanderthalensis and have even argued that many Homo sapiens today carry some “Neanderthal

DNA.” This seems a challenging notion, however, given that by the standard definition of a

14

species, the members of two species cannot interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Other scholars have interpreted the same DNA data as suggesting not that sapiens and neanderthalensis interbred, but that they shared more genetic material than expected given the differences in skeletal forms, indicating a more recent divergence from a common ancestor.

Finally, a minority view holds that the very identification of two distinct species based on skeletal forms is mistaken.

What may be clearest in this murky business is that living in a world with but a single

Homo species has spared humans of the last 40,000 years or so from confronting what would have been extraordinarily difficult ethical problems concerning how to relate to very-nearhumans. But even to say that much is speculation: and humans have, repeatedly, created problems comparable to those which biological evolution spared us, by convincing themselves that others were less fully human than they were, all biological evidence to the contrary.

15

First Farming and Some Precedents

The recovered remains of human lives from 15,000 BP differ greatly from those from

5,000 BP. From the later time, we have abundant evidence that many humans, located in different parts of the world, farmed for most of their sustenance and lived in fixed, relatively dense settlements. From the earlier date, by contrast, we have little evidence of sedentarism and none that speaks clearly of farming. It is not plausible, moreover, that the additional ten-thousand years of time would have wiped-out all, or nearly all, evidence of such practices had they been widespread in 15,000 BP. It thus seems fair to say that within this timespan, something very important happened in human history, with some notable common elements across a number of geographic sites. We can add that this span of time also saw a significant increase in the size of the human population (Figure 2.##).

Some major changes in how humans obtained their sustenance after 20,000 BP were inevitable, since there were rapid and large-scale shifts in the earth’s climate during the subsequent ten-thousand years—shifts that geologists speak of as the end of the Pleistocene era and onset of Holocene era (Figure 2.##). The Pleistocene, which had lasted for some 2.5 million years, was cooler and dryer than the Holocene, and during its final segment, as modern humans were spreading from Africa to all corners of the earth, the cooling intensified. In Europe and

North America, this led to large-scale ice-cover or glaciation (Map 2.##).

Starting around 20,000 BP, however, there was a reversal, with the earth becoming both warmer and wetter. In Europe and North America, the ice sheets receded, starting around 19,000

BP. In combination with continued hunting by humans, this led to sharp declines in— the large mammals that had been mainstays of the human diet in Europe ever since human humans arrived there, some twenty-five thousand years previously; some species went extinct. In other world

16

regions, the warmer and wetter climate led to larger and denser forests; these often replaced grasslands, disrupting the established ways humans in those areas had fed themselves. The increasingly moist climate opened up new lands for human habitation, changing some deserts to grasslands or forests; but the wetter climate also raised sea levels, submerging many previously inhabited coastal areas (and greatly limiting future archaeological research on those areas).

Significant short-term climate reversals further disrupted human sustenance practices.

Especially consequential, particularly in the northern hemisphere, was a sharp reversion to a cooler and dryer climate, from roughly 12,900-11,700 BP. During this time, environmental changes with major impact on human lives were unusually swift, occurring over mere decades, as glaciation returned to both Europe and North America. The reappearance of a warmer and wetter climate was also sudden.

Yet, as much as the Pleistocene-Holocene transition upended long-established human practices for obtaining sustenance, it did not cause the shift to farming. In Europe, for example, the calorie-rich large mammals were greatly reduced by 13,000 BP and all but gone by 12,000

BP. Yet we do not see farming anywhere in Europe until about 8,000BP, and it took another

2,000 years to spread across the continent. And there is no evidence that Europe’s population declined in the period which featured neither large mammals nor farming, and it may well have increased. Humans in Europe did not, in short, need farming to respond effectively to the serious disruptions of the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. This tells us, in turn, that when they did adopt farming, they must have had motives other than to find a way to feed themselves.

The accumulated research shows that the Neolithic Revolution model also needs revising in other ways. To start, as we previously noted, we now know that farming emerged independently in a multiplicity of sites, with the exact number not clear. One reason for the

17

recognition of additional sites has been the uncovering of evidence of farming, outside of previously known founding areas for agriculture, at dates that are too early for farming to have come from elsewhere. The onset of rice farming in both South and Southeast Asia now seems too early to have come from China, for example. Similarly, some varieties of wheat and sheep found on early Central Asian farms appear too early, and are also too distinctive, to have come from the Fertile Crescent, as had previously been thought; yet here, early farming may have emerged from a combination of independent invention and borrowings, given evidence of substantial flows between the two areas. In other cases—including, notably, New Guinea—the key has been recognizing that early farming took forms unlike that of the Fertile Crescent, and thus left very different, previously overlooked, evidence.

Recent research has also overturned the notion that the transition to farming and sedentarism involved a set sequence—in which farming led to sedentarism, rather than ever succeeding it, and animal husbandry emerged only with or after plant cultivation (a view based on early studies of the Fertile Crescent). More careful accounts of specific cases (including that of the Fertile Crescent), along with attention to the expanded roster of cases, has instead shown that these elements could arrive in any order—and did not combine in set ways.

For the Fertile Crescent— by far the best researched case—the eventual outcome is well documented: by roughly 10,000-9000 BP, we find significant sedentarism linked closely with

“mixed farming,” involving both plants and animals. Of the plants, the most important—as measured in land use, labor time, and human consumption—were cereals , specifically wheat and barley. The most important animals were sheep and goats. For the cereals, the clearest indicator of domestication—meaning that the varieties being farmed were distinct from the wild varieties that pre-dated human cultivation—is that the portion of the plant holding the grain resisted

18

shattering , and thus the dispersal of the grain by winds. Absent human intervention, shattering was an evolutionary advantage for cereals, since it facilitated seed dispersal. Humans, however, preferred plants that resisted shattering, since it meant more grain was left to harvest; by happenstance alone, moreover, these were the plants whose seeds had not dispersed and were thus most available for humans to plant. Cultivation thus led to the selection of the desired trait.

Humans also engaged in selective planting, and thus breeding, of plants with plumper grains.

And in regard to both traits, selection meant that domesticated varieties became more homogeneous than the wild species. For the animals, the primary indicator of domestication is diminished bone size, though the contrast between domesticated and wild varieties is less sharp than with cereals. Humans very likely also selected for higher yields of milk and greater responsiveness to herding by humans, often assisted by dogs—an animal that was probably domesticated even before the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (Figure 2.##). If these modifications to goats and sheep did occur, however, they did not leave material indicators that have been discerned to date.

Yet as much as we have a clear picture of the “mixed farming” outcome in the Fertile

Crescent, the path taken to arrive there is less clear—and what we do know is often surprising.

Prior to any clear cases of farming, for instance, there is evidence of various degrees of sedentarism in some locales: most fully, not surprisingly, where game animals and edible plants were relatively abundant. This appears to have been the case, for example, by 13,000 BP at Abu

Hureyra in northern Syria (Map 2.##). Moreover, going back at least to 17,000 BP, we find evidence of both systematic plant-tending activities and subsequent harvesting of cereals in the context of foraging—in some cases carried out by highly mobile communities and in others by relatively sedentary ones. The plant-tending activities here included both weeding-out undesired

19

plants from grasslands and relocating the seeds of desired plants to suitable habitats—in both cases augmenting the supply of cereals, though without evidence of domestication. There is also evidence of controlled burning to alter the landscape, so as to foster grazing by game animals, thus increasing both their numbers and their findability.

Finally, in even older remains from Ohalo II, an archeological site located near the Sea of

Galilee and dated to 23,000 BP (Map 2.##), recent research reports wild wheat and barley growing in a mix, involving specific inedible plants, that is a distinctive consequence of humans preparing soil for the cultivation of these cereals. Here, the evidence of human activity to augment the harvest of food is the co-presence of undesired “weeds” that do not ordinarily occur with wheat and barley, but which enter soil when it is abruptly cleared of previous vegetation— as happens when people convert a piece of land to farming. This indicates, in short, a late

Paleolithic practice of cultivation.

A final and important aspect of the story in this world area involves the relationship between the onset of farming and the emergence of new ideas. In the received model of the

Neolithic Revolution, hunter-gatherers were supposedly so consumed by an endless struggle to survive that they could not generate new ideas or innovations, giving them a static history (a view in sharp conflict with our discussion of Paleolithic migration and art). Farming, by contrast, gave at least some humans the leisure to invent, discover, and think new thoughts. Note that on this view, the shift in material conditions—in how sustenance is obtained—precedes and enables subsequent intellectual and cultural innovation—rather than vice-versa. Yet, this too has been questioned by recent research in archaeology, most notably by Jacques Cauvin and Ian

Hodder.

20

These scholars have argued that farming arose either following or at least along with novel practices constructing and arranging human dwellings and settlements. These practices involved incorporating representations of non-human forces of nature, such as dangerous animals and mortality, into the places humans lived. This, they argue, gave a physical and daily presence to new cultural categories of “the wild” and “the domestic,” while asserting that the latter could control the former—given that “the wild” was contained in what was now “domestic” space.

The final claim of Cauvin and Hodder is that these symbolic practices prefigured and thereby fostered the “domestication” present in farming. Their work thus argues that as much as early farming provided sustenance to humans, it emerged, in the Fertile Crescent and then Europe, for cultural reasons, rather than practical or economic ones.

Explanations that give priority to practical and economic reasons for the switch to farming often tell us, by contrast, that this switch would have required a shared idea of

“ownership,” so that persons who planted and tended crops could feel confident that they would reap the benefits of that labor. These explanations thus also point to a shift in ideas prior to or along with (and not just after ) farming, but with the specific difficulty that farming is said to need an idea that would not have arisen apart from farming. Hodder’s and Cauvin’s arguments, by contrast, avoid this chicken-and-egg problem, precisely because they do not hold that the motive for farming was for people to gain more sustenance for themselves—and thus farming, on their account, had no particular need for the notion of “ownership” or property. We should note, though, that a “culture first” explanation, of the sort Hodder and Cauvin provide, does not succeed as a general explanation of “farming”: it accounts, rather, for a particular case—that is, for a particular farming. Indeed, their approach suggests that we need to be cautious in regard to what we assume different cases of farming do and do not have in common.

21

Overall, our review of the Fertile Crescent case suggests a picture far from the Neolithic

Revolution model. Instead, early farming appears as part of a gradually-emerging combination that included many older techniques for manipulating nature; moreover, these parts did not appear in any predictable sequence. Finally, the farming-sedentarism may well have emerged for cultural rather than narrowly practical reasons. This overall picture is further supported by looking across the expanded roster of cases of early farming.

In China, for instance, we have outcomes that have many resemblances to, and are roughly contemporary with, those in the Fertile Crescent. In the Yangzi River valley, by no later than 9500 BP, we find mixed farming, involving rice and pigs, linked with sedentarism; and further north, in the Yellow River valley, we find a similar result, though with millet instead of rice, by no later than 8500 BP. Moreover, as in the Fertile Crescent, from at least the end of the

Pleistocene forward, we find evidence of substantial harvesting of wild cereals in both regions, plus evidence of a range of landscape preparing and plant-tending activities; we also find considerable variation in the degree of mobility and sedentarism, over many thousands of years before the emergence of farming. In China as well, then, farming probably did not mark a sharp break in what people ate or how they obtained their sustenance; and sedentarism, of some extent, was not entirely unknown.

What is interestingly different in the two cases, however, is that in the Fertile Crescent, ceramic vessels—which serve to store grain—do not emerge until some three thousand years after farming, even though we find ceramic figurines in the area tens of thousands of years earlier. In China, by contrast, we find ceramic vessels, apparently used for storing grain, from as early as 20,000 BP, and thus in the context of foraging rather than farming. The general lesson,

22

once more, is that there is no set developmental sequence for the pieces that came to be assembled as farming-and-sedentarism, even looking across just these two cases.

The available evidence for Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands further disturbs the notion of a single path to farming, involving a sudden departure from a long past in which humans depended for sustenance on what nature alone provided. To start, this evidence locates significant human interventions that fostered key food plants well before farming, and indeed, almost as soon as Homo sapiens entered this area. Early examples of such interventions include controlled burnings that created clearings within which various food plants (including the banana and taro) grew in greater abundance than in forested areas, as well as systematic relocations of food plants to suitable areas, in some cases moving species from one island to another. This was done by moving tubers, or cuttings, rather than seeds, since so many food plants in the region reproduce easily by vegetative means. Consequently, the emergence of farming here looks even more gradual than in the revised picture of the Fertile Crescent and China.

In the highland forests of New Guinea, for instance, humans fashioned clearings using both axes and fire from at least 30,000 BP. From then on, more and more of the landscape in

New Guinea was shaped by human activities, in some cases changing large areas of forest into grasslands. At Kuk—a site located in an intermountain river valley of the island—archaeologists have recovered post-holes and other structures, dated to roughly 10,000 BP, indicating the construction of agricultural plots—and making this, perhaps, the earliest known site of farming

(Map 2.##). A later depository at Kuk, perhaps as old as 6,000 BP, has ditches and channels that would have operated as an irrigation system.

Thus the evidence for New Guinea locates the emergence of farming there as part of a long and continuous history of human interventions, even spanning the environmental changes of

23

the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. These interventions changed not just particular species of plants, but the overall landscape—so as to augment, manage, and shape the growth of food for humans. Finally, evidence from New Guinea undermines the close link between farming and sedentarism that seems clear if one generalizes from the Fertile Crescent, or even that case plus

China: farming in New Guinea was not accompanied by a shift to dense and built-up settlements, much less urbanization.

In the Americas, there is evidence of the independent emergence of farming in at least three areas: the Andes, Mesoamerica, and what is now the eastern United States. In several ways, these cases more closely resemble first farming in the Fertile Crescent and China than in

New Guinea: in particular, American farming was also linked with sedentarism, as well as state formation (Chapter XX). We should note, however, that domesticated corn differs from its wild ancestor much more than does domesticated wheat, barley, or rice (Figure 2.##). Its domestication in Mesoamerica, around 9,000 BP, thus evidences a more sustained, and arguably a far more dogged, pursuit of selective breeding by humans than perhaps anywhere else in the world. Moreover, the primary crops of early Mesoamerican farming—corn, beans, and, somewhat later, squash—benefited from being cultivated together. Corn’s firm stalks, provide support for bean plants, which grow as vines, and useful shade for squash, which spreads along the ground; so too, bean plants—like other legumes—help replenish soil nutrients that other plants take out, by drawing atmospheric nitrogen into the soil. And since the three crops came to be grown together, rather than in monocrop fields, early farming here looked very different than in the Fertile Crescent and China.

In the Andes Mountains, in what is now Peru and Ecuador, we have evidence that potatoes were domesticated by 10,000-7,000 BP. Domestication here is indicated by a

24

proliferation of varieties, as people selected different types that were suited to the diverse microclimates found at different altitudes along steep mountainsides. Thus early domestication here meant less uniformity of potatoes than in the wild, which is exactly the opposite of what happened with wheat and barley in the Fertile Crescent. This helps explain why the Andean case has at times been overlooked by researchers committed to the received Neolithic Revolution model.

Finally, because humans arrived here far later than in the other known sites of independent domestication, we have a fuller record of life just shortly after humans first arrived than almost anywhere else in the world. This makes the Americas an interesting indicator of whether humans are likely to have been present anywhere for vast expanses of time before they began trying to control their own sustenance. In this regard, it is notable that fossilized plant materials indicate that in South America, humans probably began cultivating manioc and other roots very soon after arriving. Moreover, given that some varieties of manioc are quite toxic, this may also have involved the remarkable feat of learning how to render a poisonous plant into food. This evidence that humans acted to augment and shape their sustenance, soon after their arrival, corresponds to the findings for Southeast Asia and the Pacific that we have discussed.

Such cases make more likely that the lack of evidence of humans acting to augment and shape sustenance even earlier in the Paleolithic (in other places) may well be because that evidence has disappeared, and not because the humans then took no such actions.

Early farming in Africa is less well researched than that in any other world region. That said, there is good evidence for its independent emergence in several sites, including West

Africa, the Ethiopian highlands, the Sahel, as well as the adjacent area that is now the Sahara at a time (early in the Holocene) when it was not desert, and finally, the Nile River Valley (Map

25

2.##). It had long been thought that the Nile River Valley acquired agriculture from the Fertile

Crescent. This now seems dubious, however, given evidence that many local floodplain plants were farmed prior to any cultivation of the cereals that were probably Fertile Crescent imports.

Furthermore, Paleolithic foragers seem to have intensified their harvesting and tending of these floodplain plants before farming began, here or elsewhere. In the Sahara region, animal domestication, and subsequently pastoralism, appeared prior to and independently of agriculture.

The earliest known case involves the keeping of sheep in humanly inhabited caves, around 9,000

BP— indicated by the presence of fossilized sheep dung well inside the caves. For other sites, it is striking how unsure we are about when farming began; for the Sahel, for instance, the best evidence is that a variety of sorghum that was first domesticated there was also being cultivated in South Asia, by roughly 4,000 BP.

A final important point is that Africa too provides evidence of the use of controlled burning during the Paleolithic. Evidence for this practice at the southeast Cape of Africa has been dated to roughly 90,000 BP (MAP 2.##); if that evidence is reliable, this would be the earliest known case of such deliberate alteration of landscape by humans.

26

Is “The Neolithic Revolution” What Happened?

The notion of “the Neolithic Revolution” clearly captures a crucial point: human lives and histories after 5,000 BP differed greatly from those before 15,000 BP. Indeed, with the possible exception of changes that resulted from migration into sharply different habitats, the changes during this span of time are greater than during any previous ten-thousand period. They also underlie many subsequent large-scale, and even more rapid, changes, over the last 5,000 years. On these grounds, in short, the term “revolution” is warranted.

We should note, however, that we are talking about changes that unfolded across many millennia. In no case is there a distinct moment of the “invention” of agriculture. Instead, various more and less novel elements of farming appeared over many thousands of years, and were slowly combined as farming and, in some cases, as farming-plus-sedentarism. Thus, while we—surveying this ten-thousand year span in its entirety—see “revolutionary” differences from its beginning to end, the overall change that occurred would have been imperceptible for those who lived within it, even looking backward.

A bigger problem for the Neolithic Revolution model is that human activities that deliberately augmented and shaped sustenance, including key elements of farming, are present well before 12,000 BP. Paleolithic humans burned landscapes, and moved and replanted plants, to increase their food supplies. They may also have domesticated at least one animal: the dog— very likely, in several different places. Most estimates place this first domestication between

15,000 and 30,000 BP, and one reputable scholar has located it at roughly the time when Homo sapiens themselves first appeared.

On our view, the overall body of evidence suggests not only that deliberate human actions to control sustenance and nature preceded farming, but that such efforts may well be as

27

old as Homo sapiens themselves. Put otherwise: the idea that our species ever existed without seeking to control nature should be regarded as a speculative hypothesis, not a settled truth.

It is the case, however, that the changes that occurred between 15,000 and 5,000 BP were large in scale, and on this criterion, “revolutionary.” Another implication of identifying change as “revolutionary” is that the change in question is lasting: “revolutionary,” in short, because once farming was adopted, there was no “going back.” Here, how well the evidence fits largely depends on the timescale one considers. In the long run, farming triggered various changes that made it overwhelmingly more likely that people would adopt and stick with farming than that farmers would return to nomadism and hunting-gathering. Yet, for centuries, even millennia, after the onset of farming, many farmers did just that. This should remind us that though farming has prevailed over hunting-gathering in the long-run, this was not because it worked too well for people to imagine rejecting it. Instead, what probably mattered, as we will discuss below, was that farming bestowed a big edge in coercive power. Let us look first, however, at why early farming might not have seemed an obvious gain for those who lived it.

Early Farming and Material Well-Being

Measurements of material welfare for early farmers, where we can make them, show no clear improvement. Indeed many—probably most—show declines.

To start, workloads almost certainly increased with farming. One indication of this is from studies of hunter-gatherers in the twentieth century, which found that they needed only four to five hours per day to obtain and prepare food—and this in an era when hunter-gatherers were limited to the poorest lands. Moreover, since mobile people are generally averse to accumulating bulky possessions, the work of sustenance is most of their work. As for early farming, its work requirements varied considerably and our direct evidence is limited. But studies of farmers in

28

later in history show that farming is, at least intermittently, quite demanding. Early farmers, with fewer and poorer, tools—clay rather than metal sickles to cut cereals; wooden digging sticks rather than plows to prepare land—would have had to work even harder to raise their yields above that of foragers. Some early farmers merely cleared ground with fire, tossed seeds on the ash, and did little more until harvest time. Their farming was much less demanding, but they would have had low per acre yields, which would have been incapable of supporting dense populations. In terms of both work and output, then, they would have been much like huntergatherers.

Studies comparing skeletal evidence of work-related injuries, and wear on human joints, for early farmers and foragers show highly varied results, with farmers faring slightly better on average. The same skeletons, however, indicate that farmers generally suffered more nutritional deficits than foragers inhabiting the same area. Anemia (reflecting iron deficiencies) turns up more frequently among farmers, particularly in maize-eating parts of the Americas. Vitamindeficiency diseases were also common. A clear majority of studies comparing the average growth rates of children (a good indicator of general health conditions) before and after farming shows declines with this transition. Poor nutrition also weakens immune systems, creating greater vulnerability to infections; and as we will discuss below, farming also brought on new and dangerous infectious agents.

Consistent with these findings, life expectancy generally declined rather than increased with agriculture. A study of numerous Fertile Crescent sites found, for instance, that as holdings of domesticated livestock increased, so did childhood mortality: a growing percentage of all bodies found in graves were of infants and children. Many other studies, from many regions, tell similar stories. The impact of early farming on life expectancies for those who survived

29

childhood is unclear, but the existing research does not suggest that adult longevity improved enough to outweigh increased pre-adult death rates.

Overall, then, the material well-being of the “average” person probably deteriorated with the shift to farming; and this conclusion, once considered radical, is now well accepted.

Two Claims That Do Hold Up

One claim about the “superiority” of farming is that it supported more people. And indeed, even with the decline in material well-being, the rate of growth of the human population actually increased from roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP. That said, since the timing of both accelerated population growth and the onset of farming are hard to pinpoint, the relationship between them is uncertain. Some scholars have argued that population growth began first, so that it became necessary to increase food supplies—thus making farming the solution to a species-wide biological problem. Yet, examples like the one discussed above—in which crucial prey animals become scarce in Europe 5,000 years before our first evidence of farming there— undermine this view. We have much stronger evidence for the opposite relationship: that farming caused population increases—by greatly raising birth rates, as we will explain below.

A second valid claim about the consequences of early farming is that the impact of humans on the rest of the planet grew dramatically as farming expanded. This is almost certainly true, even in the relatively short term. Population growth alone would have increased humans’ environmental impact. Moreover, domestication, by definition, means that humans were altering other species, increasing the reproductive success of the specimens that fit human desires, rather than those otherwise “fittest” to survive.

Farming also changes land. As we have emphasized, hunting-and-gathering does this too, but the pace and scale of human impact on soil and landscapes increased with agriculture.

30

More forest was cleared, and few crops have roots that hold soil as well as trees do; none block wind as effectively. Farming thus greatly increased erosion. Moreover, fields of a single crop often became bare after harvesting; this rarely happens to “wild” land, with many different species growing on it. These farmed fields were then vulnerable to invasions by new plant species—unwanted but quite durable once established. Moreover, these two effects were sometimes synergistic: if erosion decreased yields, leading humans to abandon a farm, the site was likely to be colonized by some fast-spreading plant, with unpredictable consequences for other local species. Increased impact, then, reflected both agricultural successes and agricultural failures.

The robustness of these two claims well supports our earlier observation that the shift to farming marked a profound change—and even a revolution

—in human history. What these claims do not clearly support, however, is the notion that farming brought, or led to, a developmental advance. It is not obvious, for instance, that simply having more people on the planet constitutes either “progress” or “decline,” at least beyond the point of the population being very small, which does have risks for the species. Thus, while the acceleration of population growth with farming is of enormous historic importance, it was not distinctly an advance. And this is, if anything, even more obvious in regard to farming’s greater “impact” on other species and the environment.

Greater Control? More Unintended Consequences?

Another claim made about the consequences of the Neolithic Revolution is that it greatly increased human control

—in regard to sustenance, human survival, and—in support of these— nature. This is a less extreme claim than the one discussed above, that humans exercised no control over nature prior to farming, but it focuses on the same issue. It also resembles—but

31

goes beyond—the claim that human impact on the non-human world increased with farming.

“Control” implies that humans were able to use their impact to benefit themselves. Thus, this claim leads into what is arguably the most general and consequential aspect of the Neolithic

Revolution model: the idea that despite its detriments and discontents, the Neolithic Revolution gave rise to “progress”—and provides good evidence that this is, in fact, humanity’s overall trajectory through time. What is a more accurate picture in regard to “control,” we would argue, is that farming involved complex and uneven combinations of gains in control, along with unintended consequences, some quite harmful and difficult to manage.

To start, farming did not necessarily make sustenance more dependable. Harvests fluctuated with weather; and relying on fewer species—which is particularly characteristic of the farming that emerged from the Fertile Crescent and China—increased risks from weather, especially when farmers no longer knew how to resume effective foraging in a crisis, or became too numerous to do so.

Concentrated fields of one particular species also become more vulnerable to pests. Pests with limited mobility (such as fungi) that thrive on one particular host are unlikely to spread where highly varied vegetation leaves its targets far apart; but when their target is concentrated, pests can reach the entire crop, often quickly. Thus farming could select for precisely those pests that were most dangerous to farming; and, ironically, farmers sometimes exacerbated this problem by becoming more skillful. In Gansu (northwest China) for instance, early farmers (ca.

10,000-7,500 BP) mostly grew common millet: a crop that requires little attention, and thus suited people who also engaged in considerable hunting and gathering. By 5,000-4,000 BP, however, they mostly grew foxtail millet; it yields twice as much per acre as common millet and does better in the dryer conditions this area experienced beginning around 5,000BP. However,

32

foxtail millet is much less good at resisting diseases and at out-competing weeds: it thus required far more work, reducing time for foraging. Thus more advanced farming here supported more people, and responded successfully to climate change, but barely kept up with other, humaninduced, environmental problems. Across a range of such cases, involving unexpected difficulties with farming, we find that some farmers returned fully to foraging; others continued mixing the two; and others, as in Gansu, grew in population by doubling down on farm work, sacrificing other foods.

Greater human population, however achieved, reflects greater human control in one sense: humanity as a whole took over resources from elephants, wild boars and prairie grasses.

But humanity as a whole is a problematic historical subject: it has no consciousness, makes no decisions, and its satisfaction or dissatisfaction—which seems crucial to any assessment of

“progress”—exists only as a sum of individuals’ feelings. And it is far from obvious that the sum of individuals’ happiness will always mirror trends in humans’ share of resources vis-a-vis other species. If, for instance, rates of death and painful disease rose, but birth rates rose even faster, humans might increase their overall share of global resources without experiencing

“progress.” Indeed, this is probably what happened with early farming.

One reason that death rates rose is that farmers’ immune systems faced deadly new challenges. Living together with more people and animals, especially in small houses, spread both new and old infections. The most consequential were what are called crowd diseases : measles, smallpox, typhoid fever, rubella, and others. These diseases are mostly transmitted through contact with an infected person or animal (by breathing within roughly six feet, for smallpox); run their course relatively quickly; and require live hosts. Moreover, most victims who survive the disease are immune thereafter. Thus, in a sparse population, the disease dies

33

out, though it may kill many people first. When more potential hosts live together, however, the disease can become endemic— meaning, permanently present in a community—since there are always enough not-yet-immune hosts to sustain the virus. Significantly, we see no clear signs of such diseases before the Neolithic, but they appear soon thereafter across Afroeurasia; until the last one to three centuries, most of these diseases could not be controlled and killed in large numbers. Sedentarists in the Americas had endemic diseases also, but by happenstance, they were less deadly.

Crucially and ironically, the endemic diseases that made millions of individual sedentarists miserable nonetheless helped sedentarism spread at the expense of foragers. These diseases, however awful, did not destroy a whole society; once established, they mostly killed children, who were replaced by more births. If, however, a community not previously exposed to the disease encountered some human or (in some cases) animal carrier of it, that community was likely to suffer enormous death rates (90% in some cases), across all age groups. This happened many, many times after farming, greatly facilitating conquests by societies that had already lived with the epidemiological consequences of domestications.

If death rates—the mathematical inverse of life expectancies—rose with farming, faster population growth must reflect significantly higher birth rates. Other evidence confirms this.

Having even two small children close in age, much less more, was very burdensome for nomads, who used (and use) various techniques to avoid this. By contrast, people who milked domesticated livestock could wean their children earlier; a diet based on soft cereal-based foods

(such as rice) also facilitated early weaning. Since lactation inhibits conception, shorter breastfeeding meant more pregnancies. Farm women also spent less energy than foragers on migrating and gathering sustenance, while their diets, though poorer in nutrition, may well have included

34

more calories; this too, would have raised birth rates. Having more pregnancies and more children must have influenced women’s other roles in early farm societies, though not in any one specific way—and we lack the evidence to reconstruct them. It seems plausible, however, that more frequent pregnancies and childbirths made life harder, by some material criteria, for half of humanity—though we can say nothing about what this meant for people’s subjective feelings, of happiness for example, in any specific context.

Sedentarism certainly made it easier—even in the short run, but especially in the long run—for people to accumulate material stuff. This was not entirely a new behavior. Recall that

Paleolithic people made artworks—some portable, others fixed in place. They also carried with themselves various objects: including clothing, jewelry, figurines, spears, and axes. Moreover, the sequences in which different people acquired specific goods varied across cases, precisely because these additions were generally not matters of necessity. East Asians, we noted, began storing grain in ceramic pots long before they started farming, while western Eurasians only did so after farming.

Some material goods did presumably increase biological security: permanent shelters against the elements, for instance. But any survival benefits they conferred were likely offset by drawbacks of settling down, given the evidence of declining life expectancies. Other new things, such as the first wheels (ca. 5,500BP), probably made various tasks less painful and reduced injuries. With many other objects, however, the benefits and detriments are matters of speculation: how much happier did it make people to have, say, more or larger amulets? To be able to bury some beside a loved one? Or to not have amulets, when other people did?

As this last comment reminds us, material goods do not always or only meet physical needs: they also may mark, or even create, social statuses. Differences in housing, clothing, and

35

so on are ways that people signal numerous social distinctions: elite/non-elite, married/unmarried, adult/non-adult, local/alien and others, from contexts not our own, that are difficult for us to grasp. Claims that sedentarism constituted “progress” (even without improving health) must consider how people experience their lives—which they do within specific communities that make specific social distinctions. We are thus led to another big—but hardly positive—claim about the Neolithic: that it represented a major shift towards more sharply stratified societies.

Agriculture, Sedentarism, and Inequalities

Though we cannot assume that stratification always makes subordinate persons unhappy, many people certainly find it objectionable. Stratification also relates to the arguments about increasing human “control” of our own destinies: if Neolithic transitions didn’t necessarily improve things for most humans, might we instead show that the greater power that domestications enabled was effectively deployed to benefit some people? If so, were others deliberately excluded? How?

At least some forms of farming allowed for and arguably increased inequalities of wealth and power, along with more elaborate divisions of labor. The extent of change varied, and is not easily measured.

Most modern foraging societies are relatively egalitarian, but we cannot assume this was always the case. As already noted, most modern foragers have been forced onto marginal lands, where generating large surpluses is especially difficult. Many earlier foragers occupied richer ecological niches—and it is in precisely such settings that colonizers and early ethnographers observed some sharply stratified hunter-gatherers. Paleolithic gravesites also indicate some inequality, including hereditary inequality—signaled by children buried with many possessions.

36

On average, foraging societies probably were and are less unequal than settled ones. Simply observing this tendency does not, however, explain how farming, sedentarism, and inequality were related—especially since the results varied enormously across societies.

Some explanations highlight elite control of fixed assets needed to produce or protect agricultural wealth—such as irrigation systems or fortresses. Others claim that exchange between societies became crucial once each settled in a particular ecological niche, and argue that controlling these exchanges empowered elites. Examples include Levantine and southern

European societies that could not produce metal farm tools, and Nile Delta societies that lacked sufficient construction timber. However, such theories clearly fit only some times and places.

Much farming was done without irrigation or metal tools, for instance, and in some societies that imported metal goods, ritual objects outnumbered tools.

These theories also vary on a crucial point: did elites play valuable, difficult, managerial roles, providing a functional explanation of their privileges? Or did they just gain control of a vital social pressure point without providing special skills, making their privileges nothing but exploitation ? There have been, for instance, many sophisticated irrigation systems that operated in relatively democratic ways, needing neither a brilliant super-engineer nor a harsh taskmaster to maintain them. Nor would needing trade necessarily mean needing monopolistic traders.

Even where some vital task did require exceptional skills, this would not explain why privilege so often became hereditary; if the flood control expert dies, why assume that his son should replace him?

The above explanations emphasize control of essential functions—which may sometimes require centralized coordination. Other explanations stress that agricultural societies typically store far more resources than foragers do. They gather much of their sustenance during one or

37

two annual harvests and consume it gradually; this empowers people who can seize and redistribute stored goods, whether or not they contribute significantly to production. Most foragers, by contrast, typically consume their food soon after gathering it. Sedentarists also built permanent structures—homes, storehouses, temples, and so on—that were resources in themselves. Pastoralists stored more wealth than most foragers , but less than most sedentarists: herds were living wealth, and many pastoralists returned regularly to two or three seasonal camps, perhaps including buildings. Consistent with this, many are more hierarchical than foraging societies, while few if any equal the extremes of inequality of agricultural societies.

Interestingly, one foraging society that was unusually stratified when observed in the 19 th century—the Pomo of central California—made much of its food from acorns; annual yields of acorns vary enormously, but the Pomo developed techniques that could preserve them for over a decade.

Other arguments focus less on how stratification emerged than on why subordinated people tolerated it. The key assumption of these theories is that in the sparsely populated

Paleolithic and early Neolithic, the easiest course for groups of people who felt exploited was not to overthrow the exploiters, but to desert them, forming their own society. Nomadic huntergatherers might do this relatively easily—perhaps even harmoniously, especially if the group had become large. Among nomadic pastoralists, however, those splitting off would seek to take some of the herd; they might also need to avoid their old group’s customary campsites, perhaps sacrificing access to structures that they had helped to build. Still, the argument goes, these would be acceptable sacrifices. And knowing that others could and often did exit would restrain nomadic elites, limiting exploitation and stratification.

38

By contrast, farmers lived in places that had undergone valuable modifications. They or their forebears had eliminated unwanted trees and transplanted desirable cultivars. They might also have plowed furrows; dug irrigation ditches; started orchards years ago that now gave fruit annually, with little additional labor; terraced hillsides to allow farming without much erosion; and built houses, storehouses, and altars and graves that seemed to placate the gods and the dead. Leaving all this would not be easy; this might restrain flight, even in the face of some unfairness. Putting this differently, we could say that the build-up of fixed assets throughout sedentary societies—not only those directly controlled by elites—helped keep people in place and maintain social cohesion, notwithstanding inequality, even exploitation. Both desertions and rebellions occurred, and hierarchical societies were often held together by force. (Coercion, often involving direct violence, will figure prominently in chapter 3, which discusses emerging state systems.) But the pull exerted by accumulated resources and value was also crucial. Finally, it is noteworthy that the accumulated resources that reduced desertions included not only those which directly promoted or protected physical production, but those, such as temples, with other kinds of value.

While the importance of these and other factors varied across cases, they combine to illuminate three related patterns. First, despite reverses, agriculture spread far more rapidly than we might expect given its drawbacks and the vast areas still available for hunting, fishing, and foraging. Second, societies built around domestication, especially farming, represented far more concentrated power than did foraging societies. Third, these societies often held together even when small elites corralled most of the benefits of that power. Other changes in technology and social organization soon pushed these tendencies much further.

39

What Has Become of “the Revolution”?

As we have seen, the onset and outcomes of farming in the Neolithic marked a major shift, even a revolution, in human history. Many of the key changes—the nearly universal adoption of farming-sedentarism and the gains in both human material welfare and human control of the non-human world—seem strikingly clear if one takes the very long view and compares “then” and “now.” Such coarse-grained overviews, however, often belie lived experience and obscure other important patterns that are visible using other timescales. For instance, the average lifespan today is roughly double that of 15,000 BP; yet, lifespans first declined with farming, as we saw, and almost all of the doubling occurred only in the last 200 years. Nor is it certain that all the trends we perceive from our vantage will continue moving forward: consider, for instance, what runaway climate change would do to our sense of a clear gain in “human control” over our sustenance since the onset of farming? And recall that in a context where things were often not getting better, many people abandoned farming, particularly during the first millennia after farming emerged. What made farming and sedentarism prevalent and lasting was not that they necessarily delivered more happiness, but that they delivered more power.

In addition, a key element of the “revolution” model is undermined by various evidence that what that model treats as new in the Neolithic—purposeful innovation in general, and intentional human control of sustenance in particular—existed before farming, albeit in different forms. This too suggests that it is mistaken to see Neolithic transformations as marking a social evolutionary advance, ending the “primitive” stage of existence when humans lacked the agency and innovativeness that distinguishes human history from the natural histories of other species.

40

Finally, we would emphasize that farming and its consequences were not one thing, exemplified by the Fertile Crescent. Farming (like foraging) was a variety of practices, both adapted to different environments and responsive to different cultural projects. These different projects were influenced but not strait-jacketed by such shared material needs as food and shelter; there were some repeated patterns, but no universal laws. Taking a closer and more finegrained look shows us, then, not a singular history of the birth and advancement of “civilization, but a complex family of related histories—which we will take up in the chapters that follow.

41