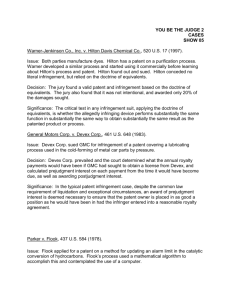

B751 Survey of Intellectual Property Prof. Janis, Fall 2011 B751

advertisement