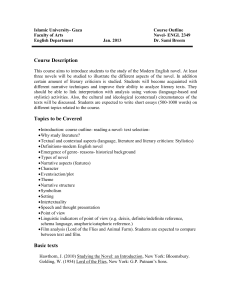

Historical Fiction

advertisement

01-20-2015 Whole-Class Novels Under what circumstances might one use this book as a whole-class novel? Why would/wouldn’t you use it as a whole-class novel? If you did use it with the whole class, what would your goals be, and what would you do (i.e., what kinds of assignments would you use) to accomplish those goals? What does it mean to “teach a novel,” anyway? To me, teaching a novel means . . . 1. The whole class reads the same novel at the same time. I assign chapters for each day. 2. We discuss the novel in class--setting, point of view, characters, plot, themes, figurative language. I help the kids make connections to their own lives and to life in general, and they make some connections themselves. Other small activities might be included (small group discussions, drawings, etc.) 3. We study vocabulary, take quizzes, do some kind of writing, and take a test on the novel. Everyone does every activity. 4. If I have a film of the novel, we watch that. If I have a video about the novel (for example, from Great Books), we watch that too. Great question. Here's my mythical historical answer. Long, long ago, venerable bearded math and science teachers looked at their colleagues, the English teachers, and mumbled, "Well, THAT'S a tough job...sit around and read stories and poems all day long..." The bearded and venerable but not so respected English teachers got together one weekend for cigars and whiskey and came up with a plan of attack. They went back to school the following Monday and launched a campaign. Secondary sources and graphic organizers tucked conspicuously under their arms at all times, they plastered the hallway with posters: "We don't read in English class. We teach novels." Years later, the signs are still up in the hallway, but "novels" have been crossed out and overwritten with "reading." (We don't read; we teach reading.) This didn't turn out to be just a rhetorical strategy as it was first intended. Now, most students actually stop reading around seventh grade, just about the time that English teachers start teaching novels. But, all in all, it wasn't a bad trade-off, because the English teachers got more respect. The students? Well, they may have stopped reading, but by god, they learn the novels! I mean, short stories. I mean, anthologized abridgments. I mean, short non-fiction selections. I mean, practice state test reading comprehension passages. I mean... Brilliant question and one that I have thought about a bit... I think we ELA teachers suffer from content-envy. Wikipedia defines this malady as a deeply rooted Freudian psychosis, often manifesting itself as a defensemechanism in response to charges that we actually teach process and skills. To "teach a novel" is one manifestation of this disease; "to teach grammar” is another; "to teach thinking" as an end in itself makes my head spin. What if we got rid of English as a course of study? Couldn't history and social science colleagues teach writing and literature? Couldn't science colleagues teach analytical thinking and reading comprehension? Couldn't foreign language colleagues teach grammar and mechanics? But, who might teach our vocabulary lists? Let's give P.E. teachers something to do... job security in these tough times. Only YOU Can Prevent Readicide Major Causes of Readicide: •Schools value development of test-takers more than they value the development of readers •Schools are limiting authentic reading experiences •Teachers are overteaching books •Teachers are underteaching books Test Prep & Testing Time Test Prep Learning Learning Test Prep Learning Test Prep Learning Time Test Prep Schools value development of testtakers more than they value the development of readers. Learning Learning Test Prep Reality Check: What do YOU read, and how/when do you read it? Who chooses your reading material? To what extent do you study the author and/or historical background? To what extent do you use “study questions”? How do you respond to what you read? (Do you write a paper? take a test?) Do you ever read (and enjoy) “light reading”? (beach reading? trash reading?) Why do you read? What do you get from reading? If your reading matched your students’ reading, how much would you read? Schools are limiting authentic reading experiences. “The reading and writing of our students [is] guided by teachers’ experiences and interests, not those of the learners. Exemplary Program: Writing Workshop in High School (Clark and Mueller, 69) Honors IV English Curriculum Anglo-Saxons: Beowulf, “The Seafarer” Middle Ages: Medieval ballads, Canterbury Tales, Sir Gawain, Morte’ D Arthur Renaissance: Sonnets (Petrarchan, Shakespearian, Spenserian), Macbeth, Metaphysical Poetry, Cavalier Poets, King James Bible, Tales of Two Cities Restoration & 18th Century: Swift, Pepys, Defoe, Johnson Romantics: Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats Victorian Age: Tennyson They need these works; there’s just no time for pleasure reading! Schools are limiting authentic reading experiences. Really? Standard E4-1: The student will read and comprehend a variety of literary texts in print and nonprint formats. Students in English 4 read four major types of literary texts: fiction, literary nonfiction, poetry, and drama. In the category of fiction, they read the following specific types of texts: adventure stories, historical fiction, contemporary realistic fiction, myths, satires, parodies, allegories, and monologues. In the category of literary nonfiction, they read classical essays, memoirs, autobiographical and biographical sketches, and speeches. In the category of poetry, they read narrative poems, lyrical poems, humorous poems, free verse, odes, songs/ballads, and epics. Indicators E4-1.8 Read independently for extended periods of time for pleasure. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.10 Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently. How often do you model reading “independently for extended periods of time for pleasure”? How much class time do you devote to this standard? Readicide Factor: The Overanalysis of Books Creates Instruction That Values the Trivial at the Expense of the Meaningful Readicide Factor: The Overteaching of Academic Texts Is Spilling Over and Damaging Our Students’ Chances of Becoming Lifelong Readers When is the last time you “slogged through to the end” of a book because you felt obligated to do so? When you did so, what did the students learn? What “collateral damage” might occur in such situations? Teachers are overteaching books. Too much is not good . . . . . . but too little is also not good. So how much instruction do students need? What’s the point of our instruction? Teachers are underteaching books. What’s the point of our instruction? E4-1.1 E4-1.2 E4-1.3 E4-1.4 E4-1.5 E4-1.6 E4-1.7 E4-1.8 Compare/contrast ideas within and across literary texts to make inferences. Evaluate the impact of point of view on literary texts. Evaluate devices of figurative language (including extended metaphor, oxymoron, pun, and paradox). Evaluate the relationship among character, plot, conflict, and theme in a given literary text. Analyze the effect of the author’s craft (including tone and the use of imagery, flashback, foreshadowing, symbolism, motif, irony, and allusion) on the meaning of literary texts. Create responses to literary texts through a variety of methods, (for example, written works, oral and auditory presentations, discussions, media productions, and the visual and performing arts). Evaluate an author’s use of genre to convey theme. Read independently for extended periods of time for pleasure. How can we accomplish these goals without “killing” the books? The Kill-a-Reader Casserole Take one large novel. Dice into as many pieces as possible. Douse with sticky notes. Remove book from oven every five minutes and insert worksheets. Add more sticky notes. Baste until novel is unrecognizable, far beyond well done. Serve in choppy, bite-size chunks. Readicide, p. 73 Gallagher’s Three Ingredients to Building a Reader 1. They must have interesting books to read. 2. They must have time to read the books inside of school. 3. They must have a place to read their books. Readicide, p. 84 Step 1: Have interesting books available (IN the classroom!) Steps 2 & 3: Provide time (in class) for pleasure reading, and, as much as possible, provide a comfortable place for pleasure reading. Make books – reading them, discussing them, recommending them to each other – a normal part of the classroom culture. Gallagher’s advice: Teach students to recognize the value that comes from reading academic texts. Start with the guided tour; end with the budget tour. Augment books instead of flogging them. Gallagher’s approach Half the reading is academic; Half the reading is for pleasure. Under what circumstances might one use this book as a whole-class novel? How might you guard against committing readicide with this book? adolescent lit? What is YA lit? juvenile lit? teen lit? Some possible descriptors: popular lit? Is something YA readers (i.e., ages 12-18) choose to read Is written from YA perspective (with age-appropriate limitations) Is written for YA audience Has YA protagonist Includes issues relevant to young people Provides vicarious experiences while revealing realities of life Sources: Literature for Today’s Young Adults, 6th ed. (Nilsen & Donelson, 2001), Young Adult Literature in the 21st Century (Cole, 2009), Young Adult Literature: Exploration, Evaluation, and Appreciation, 2nd ed. (Bucher & Hinton, 2010) Really Brief History of YA lit The Outsiders (1967, S. E. Hinton) The Pigman (1968, Paul Zindel) Go Ask Alice (1971, anonymous) ALAN becomes an independent assembly of NCTE (1973) The Chocolate War (1974, Robert Cormier) Forever (1975, Judy Blume) … Harry Potter series (1997-2009, J.K. Rowling) Twilight saga (2005-2008, Stephenie Meyer) Historical Fiction Historical setting: accurate depiction of time and place •Science and technology of the period •Religious beliefs, attitudes, and practices •Political views and conflicts •Medical technology and practices •Trends in fashion, manners, music, entertainment, etc Generally includes actual historical people and/or events Fictional characters might interact with historical characters Could be “based on” actual events Could be speculative: what could have or might have happened What would you want students to get from reading this as a whole-class novel? What might you expect them to get from reading it independently? In general, what’s the value of having historical fiction available for independent reading? Commercials, Trailers, and Reviews Commercial: Like a TV or web commercial, the goal of this activity is to create interest in the book so that listeners will want to read it. Think of the book as a product you are selling; the "sale" is successful if you get people to read the book. This is a short oral presentation -- only a minute or two, tops -- but you should have a copy of the book available for anyone who wants to take a look at it. Commercials, Trailers, and Reviews Leviathan The Best Bad Luck I Ever Had Cast Two Shadows Trailer: This is a video project. Create a short video to "sell" your book to viewers, and post the video on youtube, teachertube, or some other site we (and your students) can easily access. Like a movie trailer, a book trailer uses images, words, and music -- and it should avoid spoilers. You should look at other book trailers (which you can find by searching online for "book trailer") as models, but you are free to be as creative as you like. You should post a link to your trailer on the class wiki. Commercials, Trailers, and Reviews Review: This is a traditional review, to be posted on the class wiki, targeted to other members of the class who have not yet read the book. Include publication data, a bit of plot summary, your own commentary on the story and the writing, and any warnings about potentially controversial material. Soldier Boys, by Dean Hughes (Simon Pulse, 2001, 230 pages, $6.99) Soldier Boys is a touching story of two young boys caught on opposite sides of a terrible war. Dieter is a young German boy who has whole-heartedly bought into the ideas of Adolf Hitler and Third Reich during World War II. Spence is a young American boy who desperately wants to join the war effort to prove himself as a brave defender of freedom. Both boys find themselves exactly where they dreamed of being: on the front lines of the battle; however, it is nothing like they expected it to be. Both boys are cold, hungry, homesick, and scared. They hear battle raging around them all of the time, and they are constantly faced with the reality of death. They press on, though, because they believe so much in their countries’ cause. The boys’ lives march closer and closer together until they eventually come to the same battleground. On the first day of the battle, Spence and the Americans are overwhelmed by the Germans, and they must retreat. On the second day, though, it is Dieter and the Germans who find themselves ambushed. Dieter is severely wounded in this battle and becomes stranded for hours on the battlefield. Spence, from his fox hole, can hear Dieter calling out for help. He resolves to help Dieter, which ends up being a life-ending decision for one of the boys. Soldier Boys is a pretty clean book. It has little, if any, bad language in it, and it has no scenes of sex, drug or alcohol abuse, or other inappropriate content. It does have some parts about war and death, but they are pretty mild. Most students in middle school could read this book without being troubled by any of the content; however, high school students could probably appreciate the boys’ experiences more, as they are closer in age to them. This book could probably be used as a whole class book in order to study writer’s craft (the weaving of two stories), irony, or alternate endings. It could also be easily paired with a social studies class studying World War II. Soldier Boys lends itself to a lot of writing activities both paired with a social studies class and on its own. Students could learn a lot about war narratives and how they are written. They could also use this book to compare/contrast the “facts” about World War II that they learn in history class. Or, they could use this book as an opportunity to interview war veterans (from World War II or other wars) and write those veterans’ stories. Soldier Boys could also be used as a book club book in the classroom. It would be useful for student to discuss this book next to other war stories like The Red Badge of Courage, “The Things They Carried” or All Quiet on the Western Front. This is definitely one young adult book that could easily be integrated into most any classroom. For next week… Read a book in the “historical fiction or nonfiction” category that is set in Europe or the United States, or that relates to European or US history, but not WWI, WWII, Vietnam, or a US war in the Middle East. For your book, create one of the following: • a commercial (to be performed during class) • a video trailer (with a link on the wiki) • a book review (posted on the wiki)