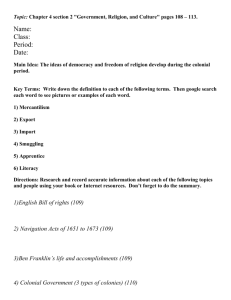

Colonial Life in 17th and 18th Centuries

advertisement

Colonial Life in the th th 17 and 18 Centuries I. Southern Society As slavery spread, gaps in the South’s social structure widened: A hierarchy of wealth and status became defined. At the top were powerful great planter families: the Fitzhughs, the Lees, and the Washingtons. By the Revolutionary War, 70% of the leaders of the Virginia legislature came from families established in Virginia before 1690. Southern Society Planter elite at top. Far beneath the planters were the small, yeoman farmers, the largest social group. Still lower were the landless whites. Beneath them were those whites serving out their indenture. Increasingly black slaves occupied the bottom rung of southern society. Southern Society Few cities sprouted in the colonial South. Urban professional class (lawyers and financiers) was slow to emerge. Southern life revolved around the isolated great plantations. Waterways were the principal means of transport. Roads were terrible. II. The New England Family Contrasts in New England life: New England settlers of 1600s added 10 years to their life span. – First generations of Puritans averaged 70 years. – They tended to migrate not as single persons but as families, and the family remained the center of New England life New England’s population grew from natural reproduction. – The New England Family Married life in New England: Early marriage encouraged a booming birthrate. Women generally married in their early twenties. They produced babies every two years. A married woman could experience up to ten pregnancies and raise as many as eight children. Longevity contributed to family stability. The New England Family Gender Roles The fragility of southern families advanced the economic security of southern women. Because men often died young, southern colonies allowed married women to retain separate title to property and inherit their husband’s estates. New England women, however, gave up property rights when they married. A rudimentary concept of women’s rights as individuals was beginning to appear in the 1600s. Women could not vote, but authorities could intervene to restrain abusive husbands. III. Life in the New England Towns New Englanders evolved a tightly knit society based on small villages and farms. Puritanism instilled unity and a concern for the moral health of the whole community. Society grew in an orderly fashion, unlike in the southern colonies. After securing a grant of land from a colonial legislature, proprietors laid out their towns. Towns of over 50 families were required to provide elementary education Life in the New England Towns 1636: Harvard was founded. Puritans ran their own churches. Democracy in the Congregational Church led to the same in government. Town meetings were examples of democracy: Elected officials Appointed schoolmasters Discussed mundane matters such as road repairs p75 IV. Population Growth A distinguishing characteristic shared by the colonies was population growth: 1700: There were fewer than 300,000 people, about 20,000 of whom were black. 1775: 2.5 million inhabited the thirteen colonies, of whom half a million were black. White immigrants were nearly 400,000; black “forced immigrants” were about the same. The colonists were doubling their numbers every twenty-five years. V. The Structure of Colonial Society America seemed a shining land of equality and opportunity, except for slavery. In New England, with open land less available, descendants faced limited prospects: Farms got smaller. Younger children were hired out as wage laborers. Boston’s homeless poor increased. In the South, large plantations continued their disproportionate ownership of slaves: The largest slaveowners increased their wealth. Poor whites increasingly became tenant farmers. The Structure of Colonial Society Colonial professions: Most honored was the Christian ministry, but by 1775 ministers had less influence than earlier. Most physicians were poorly trained. First medical school was established in 1765. Aspiring young doctors served as apprentices. At first, lawyers were not favorably regarded. – The Structure of Colonial Society Agriculture was the leading occupation, employing 90% of people Tobacco the main crop of Maryland and Virginia. Middle (“bread”) colonies produced much grain. Overall, Americans enjoyed a higher standard of living than the masses of any country. Fishing ranked far below agriculture, yet was rewarding, with a bustling commerce. Commercial ventures were another path to wealth. Map 5.2 p86 The Structure of Colonial Society Triangular trade was very profitable. Manufacturing was of secondary importance. Household manufacturing (spinning and weaving by women) added impressive output. Skilled craftspeople few and highly prized. Lumbering was the most important manufacturing activity. Colonial naval stores were also highly valued. Map 5.3 p87 VI. The Great Awakening Table 5.2 p89 Jonathan Edwards The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect over the fire, abhors you and is dreadfully provoked. His wrath toward you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else but to be cast into the fire. (1734) Reasons for Great Awakening Ministers feared “rational Christianity” that Enlightenment popularized 1730s, religious revivals began among Congregationalists and Presbyterians in Middle Colonies and New England Focused on traditional Protestant Christianity Evangelical – focused on rebirth through religious conversion Popular Ministers Jonathon Edwards Local Congregationalist Pastor, Northampton, MA Juxtaposed talk of God’s grace with portrayals of eternal damnation Individuals must express remorse and penance George Whitefield From England, traveled throughout colonies hosting revivals Led dramatic performances to thousands (B.F.) Message was similar to Edwards’, but delivery was better 5.6 p91 Impact of Great Awakening The Awakening left many lasting effects: The emphasis on direct, emotive spirituality seriously undermined the old clergy. Many schisms increased the number and competitiveness of American churches. It encouraged new waves of missionary work. It led to the founding of colleges. It was the first spontaneous mass movement. It contributed to a growing sense of Americanism. VII. Schools and Colleges Education was first reserved for the aristocratic few: Education should be for leadership, not citizenship, and primarily for males. Puritans were more zealous in education. The primary goal of the clergy was to make good Christians rather than good citizens. Educational trends: Education for boys flourished. New England established schools, but the quality and length of instruction varied widely. The South, because of geography, was severely hampered in establishing effective school systems. p92 Schools and Colleges Nine colleges were established during the colonial era Student enrollments were small, about 200. Instruction was poor, with curriculum heavily loaded with theology and “dead languages.” By 1750, there was a distinct trend toward “live” languages and modern subjects. Ben Franklin helped launch the University of Pennsylvania, first college free from any church. Table 5.3 p93 VIII. A Provincial Culture Art and culture still had European tastes, especially British. Colonial contributions: John Trumbull (1756–1843) was a painter. Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), known for his portrait of George Washington, ran a museum. Benjamin West (1738–1820) and John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) were famous painters. p93 A Provincial Culture Other colonial contributions: Architecture was largely imported and modified to meet peculiar conditions of the New World. The log cabin was borrowed from Sweden. 1720: Red-bricked Georgian style introduced. Noteworthy literature was the poetry of enslaved Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784). Benjamin Franklin wrote Poor Richard’s Almanack. Science was slowly making progress: Benjamin Franklin was considered the only first-rank scientist produced in the American colonies. IX. Colonial Folkways Everyday life was drab and tedious: Food was plentiful, but the diet was coarse and monotonous. Basic comforts were lacking. Amusement was eagerly pursued where time and custom permitted. Colonial Folkways By 1775, British North America looked like a patchwork quilt: Each colony was slightly different, but all were stitched together by common origins, common ways of life, and common beliefs in toleration, economic development, and self-rule. All were physically separated from the seat of imperial authority. These facts set the stage for the struggle to unite.