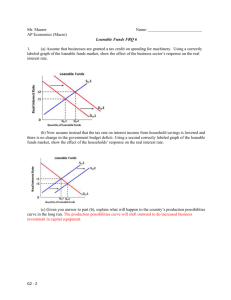

THE MARKET FOR LOANABLE FUNDS

advertisement

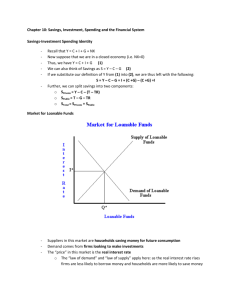

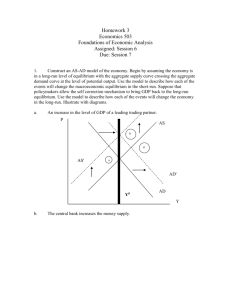

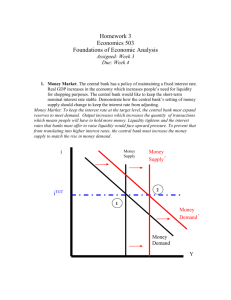

. . . are the markets in the economy that help to match one person’s saving with another person’s investment. . . . move the economy’s scarce resources from savers to borrowers. . . . are opportunities for savers to channel unspent funds into the hands of borrowers. Institutions that allow savers and borrowers to interact are called financial intermediaries. Types of Financial Intermediaries: Banks - Bond Market Stock Market - Mutual Funds Banks take in deposits from people who want to save and make loans to people who want to borrow. Banks pay depositors interest and charge borrowers higher interest on their loans. Banks help create a medium of exchange, by allowing people to write checks against their deposits. A bond is a certificate of indebtedness that specifies obligations of the borrower to the holder of the bond. Characteristics of a bond: Term: the length of time until maturity. Credit Risk: the probability that the borrower will fail to pay some of the interest or principle. Tax Treatment: municipal bonds on which taxes are deferred on the interest. Stock represents ownership in a firm, thus the owner has claim to the profits that the firm makes. Sale of stock infers “equity finance” but offers both higher risk and potentially higher return. Markets in which stock is traded: New York Stock Exchange American Stock Exchange NASDAQ Mutual Funds is an institution that sells shares to the public and uses the proceeds to buy a selection, or portfolio, of various types of stocks, bonds, or both. Allows people with small amounts of money to diversify. Other financial intermediaries include: Savings and Loans Associations Credit Unions Pension Funds Insurance Companies Loan Sharks Recall: GDP is both total income in an economy and the total expenditure on the economy’s output of goods and services: Y(GDP) = C + I + G + NX Assume a closed economy: Y=C+I+G National Saving or Saving is equal to: Y-C-G=I=S National Saving or Saving is equal to: Y - C - G = I = S or S = (Y - T - C) + (T - G) where “T” = taxes net of transfers Two components of national saving: Private Saving = (Y - T - C) Public Saving = (T - G) Private Saving is the amount of income that households have left after paying their taxes and paying for their consumption. Public Saving is the amount of tax revenue that the government has left after paying for its spending. For the economy as a whole, saving must be equal to investment. Savers and borrowers are matched up with one another through markets governed by supply and demand of the loanable funds. Economists work with a simplified model in which they assume there is just one market that brings the ones who want to lend money (savers) together with the ones who want to borrow (firms with investment projects). This hypothetical market is known as the loanable funds market. The price that is determined in this market is the interest rate (r). The interest rate is the return a lender receives for allowing borrowers the use of a dollar for one year, calculated as a percentage of the amount borrowed. The interest rate can be measured in real or nominal terms (with or without the expected inflation included). However, in real life neither the borrowers nor the lenders know what the future inflation rate will be when they make a deal, so the loan contracts specify a nominal interest rate, and the model is drawn with the vertical axis measuring the nominal interest rate for a given expected future inflation rate. The interest rate can be measured in real or nominal terms (with or without the expected inflation included). However, in real life neither the borrowers nor the lenders know what the future inflation rate will be when they make a deal, so the loan contracts specify a nominal interest rate, and the model is drawn with the vertical axis measuring the nominal interest rate for a given expected future inflation rate. As long as the expected inflation rate does not change, changes in nominal interest rate also lead to changes in the real interest rate. On the model for the loanable funds market, the horizontal axis shows the quantity of loanable funds, and the vertical axis shows the interest rate (the price of borrowing). Interest Rate Loanable Funds The demand curve for loanable funds slopes downward, because the decision for a business to borrow money to finance a project depends on the interest rate the business faces and the rate of return on its project (which is the profit earned on the project, expressed as a percentage of its cost): Rate of return = 𝑅𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡−𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑓𝑟𝑜𝑚 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡 𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡 X 100 A business will want a loan when the rate of return on its project is greater than or equal to the interest rate. The lower the interest rate, the larger the total quantity of loanable funds demanded. Therefore, the hypothetical demand curve of loanable funds slopes downward. Interest Rate Demand Loanable Funds The interest rate is also an important factor for analyzing the supply of loanable funds. Savers incur an opportunity cost when they lend to a business (the alternate use of these funds). Whether an individual decides to become a lender or not depends on the interest rate received in return. More people are willing to forgo current consumption and make a loan when the interest rate is higher. Therefore, the hypothetical supply curve of loanable funds slopes upward. Interest Rate Loanable Funds The equilibrium interest rate is the interest rate at which the quantity of loanable funds supplied equals the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The market for loanable funds matches up desired savings with desired investment spending; in equilibrium, the quantity of funds that savers want to lend is equal to the quantity of funds that firms want to borrow. Interest Rate Supply Movement to equilibrium is consistent with principles of supply and demand. 5% Demand $1,200 Loanable Funds The match-up of savers and borrowers is efficient for two reasons: 1. The right investments get made (the investment projects that are actually financed have higher rates of return than that of the ones that do not get financed). 2. The right people do the saving (the potential savers who actually lend funds are willing to lend for lower interest rates than those who do not). The equilibrium interest rate changes when there is a shift of the demand curve for loanable funds, the supply curve for loanable funds, or both. Factors that cause the demand curve for loanable funds to shift: 1. Changes in perceived business opportunities 2. Changes in government spending An increase in the demand for loanable funds causes the demand curve for loanable funds to shift to the right, increasing the quantity demanded of loanable funds to increase at any given interest rate, and the equilibrium interest rate rises. Interest Rate Supply 6% 5% Demand $1,200 $1,300 Loanable Funds An increase in the government’s deficit shifts to demand curve for loanable funds to the right, which leads to a higher interest rate. If the interest rate rises, businesses will cut back on their investment spending. So, a rise in the government budget deficit tends to reduce overall investment spending. This negative effect of government budget deficits on investment spending is called crowding out. The factors that can cause the supply of loanable funds to shift are: 1. Changes in private savings behavior 2. Changes in capital inflows An increase in the supply of loanable funds means that the quantity of funds supplied rises at any given interest rate, so the supply curve shifts to the right, and the equilibrium interest rate falls. Interest Rate Supply 5% 4% Demand $1,200 $1,300 Loanable Funds The most important factor affecting interest rates over time is changing expectations about future inflation, which shift both the supply and the demand for loanable funds. The distinction between nominal interest rate and the real interest rate: Real interest rate=Nominal interest rate – Inflation rate The true cost of borrowing is the real interest rate, not the nominal interest rate. The expectations of borrowers and lenders about future inflation rates are normally based on recent experience. According to the Fisher effect, an increase in the expected future inflation drives up the nominal interest rate, leaving the expected real interest rate unchanged. Both lenders and borrowers base their decisions on the expected real interest rate. As long as inflation is expected, it does not affect the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds or the expected real interest rate; all it affects is the equilibrium nominal interest rate. Using the liquidity preference model, a fall in the interest rate leads to a rise in investment spending (I), which then leads to a rise in both real GDP and consumer spending (C). It also leads to a rise in savings, since at each step of the multiplier process, part of the increase in DI is saved. According to the savings-investment spending identity, total savings in the economy is always equal to investment spending. When a fall in the interest rate leads to higher investment spending, the resulting increase in real GDP generates exactly enough additional savings to match the rise in investment spending. According to the liquidity preference model, the equilibrium interest rate in the economy is the rate at which the quantity of money supplied is equal to the quantity of money demanded in the money market. According to the loanable funds model, the equilibrium interest rate in the economy is the rate at which the quantity of loanable funds supplied is equal to the quantity of loanable funds demanded in the market for loanable funds. Both the money market and the market for loanable funds are initially in equilibrium with the same interest rate. This fact will always be true. If the Fed increases the money supply: 1. In the liquidity preference model, this pushes the money supply curve rightward, causing the equilibrium interest rate in to market to fall, moving to a new short-run equilibrium interest rate. 2. In the loanable funds market model, in the short run, the fall in the interest rate due to the increase in the money supply leads to a rise in real GDP, which leads to a rise in savings through the multiplier process. This rise in savings shifts the supply curve for loanable funds rightward, and reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market. Since savings rise by exactly enough to match the rise in investment spending, so this tells us that the equilibrium rate in the loanable funds market falls to exactly the same as the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market. In the short run, the supply and demand for money determine the interest rate, and the loanable funds market follows the lead of the money market. When a change in the supply of money leads to a change in the interest rate, the resulting change in real GDP causes the supply of loanable funds to change as well. In the short run, an increase in the money supply leads to a fall in the interest rate, and a decrease in the money supply leads to a rise in the interest rate. In the long run, however, changes in the money supply don’t affect the interest rate. If the money supply rises, this initially reduces the interest rate. However, in the long run, the aggregate price level will rise by the same proportion as the increase in money supply. A rise in the aggregate price level increases money demand in the same proportion. So in the long run, the money demand curve shifts rightward, and the equilibrium interest rate rises back to its original level. In the loanable funds market, an increase in the money supply leads to a short-run rise in real GDP, and shifts the supply of loanable funds rightward. In the long run, real GDP falls back to its original level as wages and other nominal prices rise. As a result, the supply of loanable funds, which initially shifted rightward, shifts back to its original level. In the long run, changes in the money supply do not affect the interest rate. What determines the interest rate in the long run is the supply and demand for loanable funds. In the long run the equilibrium interest rate is the rate that matches the supply of loanable funds with the demand for loanable funds when the real GDP equals potential output. Financial markets coordinate borrowing and lending and thereby help allocate the economy’s scarce resources efficiently. Financial markets are like other markets in the economy. The price in the loanable funds market - interest rate - is governed by the forces of supply and demand.