Resilient Therapy with children and families

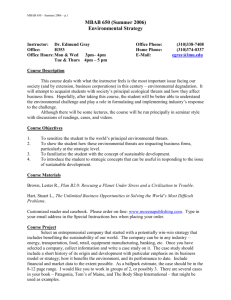

advertisement

Using resilience theory and practice to improve emotional wellbeing and community cohesion Professor Angie Hart University of Brighton What do we want to do today? • Help make sense of the most relevant research on resilience • Demonstrate the relevance to schools of Resilient Therapy, a user-friendly approach that can be used by practitioners, parents and children themselves What is Resilience? ‘…refers to a class of phenomena characterised by good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development’ (Masten 2001) Resilience is… • Playing a bad hand well, rather than getting a good hand Ways of thinking about resilience • ‘Adequate provision of health resources necessary to achieve good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development.’ (Ungar 2005b: 429) • ‘Resilience is an emergent property of a hierarchically organized set of protective systems that cumulatively buffer the effects of adversity and can therefore rarely, if ever, be regarded as an intrinsic property of individuals.’ (Roisman, Padrón et al. 2002: 1216) For example, some very obvious ones… • To achieve their maximum potential kids will be protected by having all the things we know they need: • • • • • • • good education love and sense of belonging decent standard of living great parenting intelligence good looks opportunities to contribute Vulnerability factors • Family: Poor, large families, parents with low self-esteem, parents’ own history of maltreatment, family breakdown, physical and mental illness and a range of other contextual factors (Iwaniec et al 2006) • Child: Children with special needs especially vulnerable What is Resilience? • A name for a set of processes showing that little things can make a massive difference • Very much about what we can do, not something a child just gets born with • A concept that has a vast research base behind it and which can usefully structure our strategic responses and practice decision making • Rutter: 'Therapeutic actions need to focus on steps that may be taken in order to reduce negative chain reactions…Protection may also lie in fostering positive chain reactions, and these, too, need attention in therapeutic planning’ (Rutter, 1999: 137) Implications • Some kids do better than others having had very similar experiences – we can be the factor that makes a massive difference • Complexity theory: small changes, big effects; and we can’t always see the protective effects immediately –daring to do things differently, being open minded, confident • There is hope for everybody! Resilience theory helps us to work relentlessly towards better outcomes– helps us keep enthusiastic and focused • Resilience theory gives us a framework within which to plan positive chain reactions with and for individual children (and for yourselves), and to reduce negative ones • For young people doing risky things it is still really helpful to get some protective processes going Resilient Therapy • RT strategically harnesses selected therapeutic principles and techniques • Can be used across contexts and by different practitioners, including parents and young people themselves • Designed to work in people) as co-collaborators in the development of the methodology rather than as recipients • Is user-friendly and readily accessible – you don’t need a lengthy specialised training • Non-pathologising – ‘upbuilding’ Interventions that are proving to have potential -clubs and hobbies -summer camps -belonging to something good (families, peer groups etc.) - -doing good, volunteering etc. -being paid -holistic interventions that don’t just tackle ‘the issues’ or ‘one issue’ -having mentors who stick with disadvantaged kids over time (challenge to ‘projects’ and specialisation) -Using the mass media (celebs) - exploiting the full potential of the internet, mobile phones and other new technologies (Youth matters) Basic References Aumann, K., and Hart, A. Forthcoming (2009) Helping children with complex needs bounce back: Resilient Therapy for parents and professionals. Jessica Kingsley: London Hart, A., Maddison, E., and Wolff, D.(eds) (2007) Community-university partnerships in practice Niace:Leicester ISBN 978-1-86201-317-9 Hart, A. and Aumann, K. (2007) ‘An ACE way to engage in communityuniversity partnerships: Making links through Resilient Therapy’, in A. Hart, E. Maddison, and D. Wolff,(eds) Community-university partnerships in practice Niace:Leicester Hart, A., Maddison, E. and Wolff, D. (2007) ‘Introduction’, in A. Hart, E. Maddison, and D. Wolff (eds) Community-university partnerships in practice Niace:Leicester References continued Hart, A. and Wolff, D. (2007) ‘View to the future: What have we learnt and where might we go next?’, in A. Hart, E. Maddison, and D. Wolff (eds) Community-university partnerships in practice Niace:Leicester Hart, A. and Blincow, D. with Thomas, H. 2007 Resilient Therapy with children and families Brunner Routledge: London ISBN 978-0-41540384-9 Hart, A. and Luckock, B. (2006) ‘Core principles and therapeutic objectives for therapy with adoptive and permanent foster families’, Fostering and Adoption 30(2) 29-42 Hart, A. and Wolff, D (2006) ‘Developing local “Communities of Practice” through local community-university partnerships’, Planning, Practice & Research 21:1, 121-138 References continued Iwaniec, D., Larking, E. & Higgins, S. (2006) Research Review: Risk and resilience in cases of emotional abuse. Child & Family Social Work 11 (1), 73-82 Masten, A.S. (2001) ‘ Orginary magic: Resilience Processes in Development’. American Psychologist 56, 3,.227-238. Roisman, G.I., Padrón, E., Sroufe, L.A., & Engeland, B. (2002) ‘EarnedSecure Attachment Status in Retrospect and Prospect. Child Development 73,4, 1204-1219. Rutter, M. (1999) ‘Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for Family Therapy’. Journal of Family Therapy 21, 119-144. The quote in the Introduction is from page 135. Ungar, M. (ed.) (2005) Handbook for working with children and youth: Pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts. Thousand Oaks & London: Sage Publications