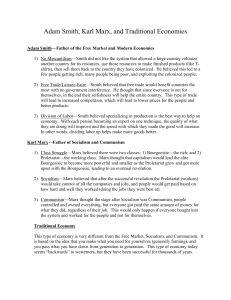

SOCIALISAM AND COMMUNISM: MORE TO MARX Thomas More

advertisement

SOCIALISAM AND COMMUNISM: MORE TO MARX Thomas More, “Utopia” Written more than three centuries before Karl Marx was born, Thomas More’sUtopia (1516) is a scathing attack on private property and the evils allegedly attendant to it. It is worth noting that More was not an atheist, but a deeply religious man who was later executed for his refusal to compromise his religious principles, and posthumously declared a saint by the Catholic Church. This shows that one need not be godless to find private property problematic; indeed many Christians have thought it so, arguably going back to Jesus himself. More invented the term “Utopia” as something of a pun, a play on Greek words that sounded the same but had two very different meaning—one meant “good place” or “happy place,” while the other meant “no place.” In any event, in the good place that is no place called Utopia, it is clear that all the social and political ills flow from private property, and that happiness results from its abolition. As More notes, following Plato, the founder of Western political philosophy, in important respects, “The only way to promote the well-being of the public as a whole is to establish equality of all goods. Such equality can never be found where every man’s goods are his private property. For there every man lays claim to as much as he can get. Then, no matter how great the abundance, a few divide all the riches among themselves, leaving the rest in poverty” (p. 190). Robert Owen, “Address to the Inhabitants of New Lanark” Robert Owen was a nineteenth-century British capitalist who became deeply troubled by the social side-effects of capitalism. Rather than attributing crime and such social ills as drunkenness and debauchery to inherent defects in human nature, Owen came to see these as the effects of a fundamentally unjust society defined by private ownership of the means of production. Accordingly, Owen came to advocate a decentralized, cooperative system of production for public profit, and an entirely new system of education. One of the communities founded on these principles was at New Lanark, in Scotland, and it is to the workers of that community that the following speech is given. The key assumption in Owen’s argument is that human character is entirely a product of the environmental circumstances that produce it, consequently “any habits and sentiments may be given to mankind” (p. 197). Owen therefore believed that by reconstructing the manner in which human beings produce things, and educating them in a radically new way, it would be possible “not only to withdraw vice, poverty, and, in a great degree, misery, from the world, but also to place every individual under circumstances in which he shall enjoy more permanent happiness than can be given to anyindividual under the principles which have hitherto regulated society” (p. 197). Eventually, under cooperative socialism, he believed that “the interest of each individual will be in strict unison with the interest of every individual in the world” (p. 199). Such claims would later be derided by Karl Marx and his collaborator Friedrich Engels as “utopian socialism,” a romantic vision incapable of being implemented and of enduring very long anywhere. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The Communist Manifesto” In 1848, with the assistance of his collaborator and co-author Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx wrote and published the Manifesto of the Communist Party.In it, Marx and Engels provided an intentionally simplified, straightforward explication of Marx’s view of history. They also discussed how that historical understanding led them to understand their own society, and connected their analysis to a particular set of goals for those calling themselves communists. The Manifesto is therefore both a brief summary of Marx’s theory and a practical plan of political action. Marx and Engels begin the Manifesto with the famous claim: “The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles” (p. 201). This was true in the ancient and feudal worlds, they argued, and is equally true under capitalism. However, the distinguishing feature of capitalist class struggle is that is has been simplified down into a battle between two great contending classes, the “bourgeoisie” and the “proletariat.” The bourgeoisie are the owners of the means of production; in capitalism, these are best understood as things like factories which make products (i.e., the “capital” in capitalism). The bourgeoisie are locked in conflict with the proletariat, a group defined by the fact that they own nothing but their “labor power,” or their ability to labor, which they are forced to sell as a commodity to the bourgeoisie for a wage, merely in order to survive. The Manifesto describes how these two classes arose historically from earlier forms of class struggle. The bourgeoisie were themselves once a revolutionary class that arose within feudal society and eventually overthrew its “relations of property,” or existing relations of production, built on lords, manors, and serfs. However, the process of class struggle did not stop there, and Marx and Engels tell their readers that “a similar movement is going on before our eyes” (p. 203). By placing the means of production, or capital—what Marx calls “private property”—into the hands of a very small group, and relegating the overwhelming number of people into desperate poverty, “the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself.” Moreover, Marx says, “it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletariat” (p. 204). And, for Marx, since the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie, were only about 5-10% of the population, and the proletariat was 90-95% of the population, the revolution that destroyed capitalism would be fundamentally different than all others which had preceded it: “All previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interests of minorities. The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interests of the immense majority” (p. 206). Thus, Marx understood the proletariat as a “universal class” that, by freeing itself, would thereby stop the motor of all previous historical change, which was built on class struggle. Since there would only be one victorious class, the revolution that ushered in communism would, he believed, be the last one. In the Manifesto, Marx and Engels describe the fall of the bourgeoisie and the victory of the proletariat as “equally inevitable” (p. 207). All that was required was for the proletariat to unite on the factory floor, come to understand the “objective” causes of their oppression, and act to transform their world, and thus the world at large. Karl Marx, “On the Materialist Conception of History” In this brief but dense excerpt, Karl Marx tries to outline and briefly summarize his theory of history. Marx once wrote that his philosophy of history could be read as an attempt to stand the German philosopher Hegel, who greatly influenced him, on his head. What he meant by this was that he thought Hegel was right in seeing history “dialectically”; that is, as a process driven by tensions internal to particular historical moments. However, Marx thought that Hegel was wrong in assuming that the motor for history was the tension between competing ideas that fought it out with one another and culminated in a new and higher historical synthesis. Rather, Marx believed that the real motor for historical change was the dialectical tension within the underlying material world, rather than at the level of ideas. Specifically, he claims that in every society, eventually the “material productive forces of society,” or group(s) of people with the ability to use specific tools and technology necessary for production, ultimately “come in conflict with the existing relations of production” (p. 214). These latter are the immediate social arrangements in which production takes place or, as Marx calls them, “the property relations” governing a society. All history is thus driven by a conflict between some people with the ability to use existing technologies in the productive process (the material forces of production), and other people who benefit from an existing set of property relationships (or relations of production). These groups form classes and, as Marx said in the Manifesto, all history is therefore the history of class struggle. The relations of production varied over time: the household and its slaves in the ancient world, manors with lords and serfs in the medieval world, and a competitive marketplace with private property ownership in the capitalist world. Nevertheless, the motor driving historical change always remained that of class struggle. Together, the clash between the forces and relations of production constitutes the real, material “base” or “foundation” of every society, and the ideas that exist within any society pertaining to law, politics, morality, religion, etc., are largely determined by the victors in that class struggle. Marx called this world of ideas and institutions the “superstructure,” and ultimately saw it as an ideological tool used by the ruling class in their own interest.