INDIANA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION 2015 LEGAL ETHICS ESSAY

advertisement

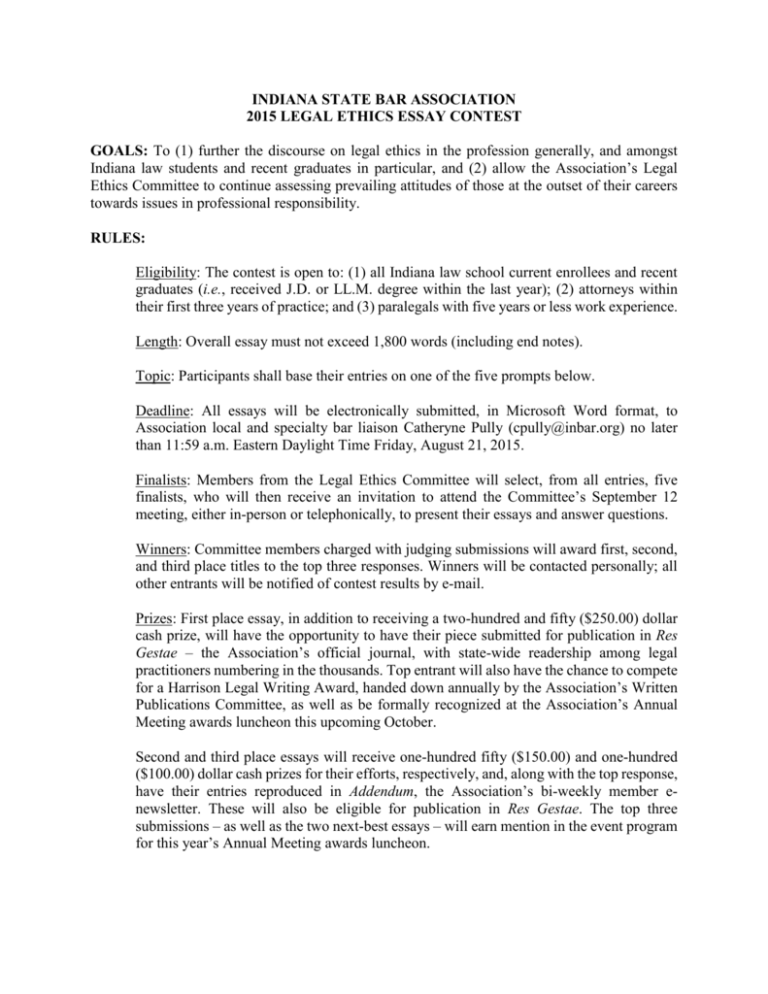

INDIANA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION 2015 LEGAL ETHICS ESSAY CONTEST GOALS: To (1) further the discourse on legal ethics in the profession generally, and amongst Indiana law students and recent graduates in particular, and (2) allow the Association’s Legal Ethics Committee to continue assessing prevailing attitudes of those at the outset of their careers towards issues in professional responsibility. RULES: Eligibility: The contest is open to: (1) all Indiana law school current enrollees and recent graduates (i.e., received J.D. or LL.M. degree within the last year); (2) attorneys within their first three years of practice; and (3) paralegals with five years or less work experience. Length: Overall essay must not exceed 1,800 words (including end notes). Topic: Participants shall base their entries on one of the five prompts below. Deadline: All essays will be electronically submitted, in Microsoft Word format, to Association local and specialty bar liaison Catheryne Pully (cpully@inbar.org) no later than 11:59 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time Friday, August 21, 2015. Finalists: Members from the Legal Ethics Committee will select, from all entries, five finalists, who will then receive an invitation to attend the Committee’s September 12 meeting, either in-person or telephonically, to present their essays and answer questions. Winners: Committee members charged with judging submissions will award first, second, and third place titles to the top three responses. Winners will be contacted personally; all other entrants will be notified of contest results by e-mail. Prizes: First place essay, in addition to receiving a two-hundred and fifty ($250.00) dollar cash prize, will have the opportunity to have their piece submitted for publication in Res Gestae – the Association’s official journal, with state-wide readership among legal practitioners numbering in the thousands. Top entrant will also have the chance to compete for a Harrison Legal Writing Award, handed down annually by the Association’s Written Publications Committee, as well as be formally recognized at the Association’s Annual Meeting awards luncheon this upcoming October. Second and third place essays will receive one-hundred fifty ($150.00) and one-hundred ($100.00) dollar cash prizes for their efforts, respectively, and, along with the top response, have their entries reproduced in Addendum, the Association’s bi-weekly member enewsletter. These will also be eligible for publication in Res Gestae. The top three submissions – as well as the two next-best essays – will earn mention in the event program for this year’s Annual Meeting awards luncheon. GUIDELINES: 1. Essays are to be in typewritten, using either Times New Roman or Book Antiqua font, 12-point type. 2. Essay text is to be double-spaced, with one-inch margins on either side. 3. Essay pages are to be lower-right numbered, complete with author’s name. 4. Essay notes and citations are to be entered using the Bluebook legal style. 5. Essays are to reference at least one of the following legal authorities: the Indiana Rules of Professional Conduct; the Indiana Rules for Admission to the Bar and the Discipline of Attorneys; Indiana Court of Appeals (for-publication or reclassified memorandum) decisions; Indiana Supreme Court opinions. Essays are free, of course, to additionally reference: American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct; rules and case law governing ethical conduct and professional responsibility in other United States jurisdictions; exceedingly persuasive secondary sources. PROMPTS: 1. The Indiana Rules of Professional Conduct require a lawyer to “provide competent representation to a client.” Comment [2] to that Rule clarifies that “A lawyer need not necessarily have special training or prior experience to handle legal problems of a type with which the lawyer is unfamiliar … [a] lawyer can provide adequate representation in a wholly novel field through necessary study.” In an era of increasing lawyer specialization, is the Comment still true? If not, and it bears revising, what should the revised comment say? 2. As evidenced by Wisner v. Laney, 984 N.E.2d 1201 (Ind. 2012), Indiana courts have made clear that attorneys are obligated to behave in a “civil” manner when engaged in the practice of law. Federal courts also share this view; Flomo v. Bridgestone, 2010 WL 935553. However, the Indiana Rules of Professional Conduct neither explicitly impose such a burden, nor do they directly address its scope. Discuss (a) the source of this duty; (b) how it is defined; (c) whether it should be considered an “ethical” duty; and (d) how lawyers are to be disciplined for transgressions of said duty. 3. Technology has touched every part of our lives, complete with concomitant benefits and pitfalls. A paralegal in your workplace, having logged nearly four decades of service in our field, waxes nostalgic on the trials of going from a simple IBM Selectric typewriter in the early 80’s to the wide range of highly-advanced programs now in daily use. Then drawing your attention to the American Bar Association’s 2012 formally-approved change to the Model Rules of Professional Conduct (amending Comment [8] to Model Rule 1.1), she notes that multiple states have since have incorporated some duty of “technological competence” into their rules, with some even going as far as to issuing advisory (and, in some cases, disciplinary) opinions on the subject. How do you react to her argument that Indiana also should change its rules accordingly, making it clear that lawyers must not only maintain a basic level of professional competency, but also keep pace with rapidly changing technology? 4. Full-time law students, by current American Bar Association accreditation standards for all law schools, are enjoined from working more than twenty (20) hours per week while so enrolled. In demonstrating compliance with these requirements, schools are actually beginning to demand that students certify the number of hours they work while enrolled in classes – generally, under the auspices of each institution’s “honor code.” In light of today's competitive job market, discuss the implications, per our Rules of Professional Conduct, for both the student who may effectively violate this guideline and the legal employer seeking to entice such students to work more weekly hours than presently permissible. 5. Fanciful Industries has a patent on a design for a “better” mousetrap, and has been directly marketing that “better” mousetrap to various retailers. Rodent Enterprises, a competitor, markets its own mousetrap to other retailers. Fanciful believes that the Rodent trap infringes on its patent, and hires the law firm of France & England to bring a patent infringement action against Rodent. In that action, it seeks damages for Rodent’s direct infringement. It also seeks damages against Rodent for indirect infringement – for having induced Rodent’s customers to infringe on Fanciful’s patent. Lastly, it seeks injunctive relief enjoining Rodent (and others in active concert with Rodent) from infringing on Fanciful’s patent. Rodent denies infringement, and otherwise challenges the validity of Fanciful’s patent. As the case progresses, Fanciful’s discovery requests to Rodent reveal, inter alia, Rodent’s customer list, containing names and addresses of numerous retailers. France & England thus determine – for the first time – that one of its labor and employment clients is a wholesale purchaser-retail seller of Rodent’s trap. Should France & England be disqualified from representing Fanciful on these facts? If not, are there any limitations on France & England’s continued representation of Fanciful?

![Submission 68 [doc]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008000926_1-fed8eecce2c352250fd5345b7293db49-300x300.png)