5.0 Continental Glaciation

advertisement

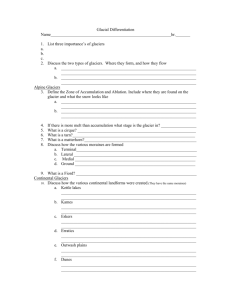

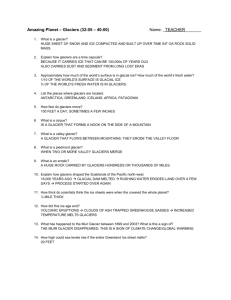

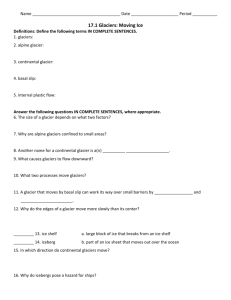

Glaciers Louis Agassiz In 1837 Louis Agassiz, a Christian geologist, proposed the “glacial theory” that the earth had years ago been covered with huge ice sheets (up to 3 km thick) that formed some of the land features seen today. His theory was ridiculed at the time, but has since been shown to be correct supported by countless lines of evidence. Drill Core Evidence Drill cores from deep sea sediments and ice layers in Antarctica and Greenland have shown that ice sheets advanced and retreated a number of times during the Pleistocene era (2 million years ago to present). Scientists feel that we are presently in an interglacial period (a warming time with glacier melting) but that we are still overall in the glacier period of our planet. Glaciation Even in Ancient Times From its earliest history, our planet has had periods of glaciation, sometimes very extensive. Today glaciers are the largest reservoir of freshwater on earth. The Causes of Glaciation Glaciers form and advance as the earth goes through a cooling cycle. The causes for these cooling cycles could be many. One key factor is thought to be the amount of CO2 (carbon dioxide) and CH4 (methane). These gases are greenhouse gases and tend to trap radiation energy in the earth’s atmosphere which raises the temperature of the earth. The Causes of Glaciation Volcanic activity produces much of these gases so lower volcanic activity could cool the planet. Changes in the earth’s orbit, changes in the sun’s radiation, tectonic movements and changes in ocean currents might also influence glacier retreat or advance. Maximum Extent of Glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere Global glaciers put much of the earth’s liquid water into a solid state which caused the world ocean levels to drop. General Effects of Glaciation The white ice caps had more albedo (degree of light reflection) which cooled the northern ice cap. The tropical areas had about the same temperatures as before but the warm belt from the equator shrunk dramatically so that temperate regions were much cooler. This affected vegetation and animals in the temperate zones. How a Glacier Forms With sufficient cold and annual moisture falling as snow, layers of snow build up and compress lower layers into ice crystals called firn. Firn is ice with many air pockets between the ice crystals. With continued pressure from upper layers of firn and snow, the firn is squeezed into solid glacial ice. It can take up to 100 years and 100 m of firn to make glacial ice in a climate that is below freezing year round. In climates with warmer months above freezing, snow and firn may melt and form glacial ice in only two years under 10-15 m of firn. What Makes Glaciers Flow Pressure on firn and ice has three effects that leads to downward movement. Pressure on firn causes its ice crystals to flatten and slip past each other which allows ice to flow downslope in a process called plastic deformation. Pressure also causes shearing which is when ice forms cracks and blocks that slip past each other. Finally pressure melts ice along the bottom of the glacier which creates a liquid layer that acts as a lubricant, allowing basal slippage. Rates of Glacier Movement Glaciers can move from 1m/day to 30m/day (Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier in Greenland). At times glaciers surge or move faster than they typically do. If they move more than 1 km/year, glaciers generate earthquakes which can have magnitudes up to 6.1. Greenland has this type of earthquake from July-September. Uneven Movement Within a Glacier Friction at the sides of a glaciers slows movement at the edges while the middle section and especially the top section moves faster. A glacier moves outward in all directions unless landforms channel it in certain directions. Glacial Ice: Always in Motion The front or snout of a glacier will move forward if the deposition of snow and firn exceeds the melting of the glacier, will retreat backwards if the melting exceeds snow deposition and will remain stationary if deposition and melting are balanced. But even with retreating or stationary glaciers, the ice beneath keeps moving downhill, never standing still. Glacier Erosion Processes: Abrasion Glacier rubbing at its base against its substate is referred to as abrasion. This removes weaker rock materials which become embedded in the base of the glacier and which scour further bedrock from the substrate like sandpaper. The rocks and boulders embedded at the base of the glacier leave scratches called striations and smaller embedded grit often polishes the bedrock. Glacier Erosion Processes: Glacial Plucking In warmer summers, meltwater from the glacier seeps into the bedrock beneath a glacier. Later when the water freezes, it may break apart the bedrock and become attached to the bottom of the glacier in a process called glacial plucking which leaves holes that are smoothed and deepened. Glacier Erosion Processes: Glacial Ploughing The weight of a glacier often is sufficient to push apart and carry away obstructions like hills or ridges and this is called glacial ploughing. Two Types of Glaciers Continental glaciers are major, continuous sheets of ice covering a large part of a continent or island. Alpine glaciers are mountain glaciers that form in upland mountain areas in valleys and basins. Features Left by Continental Glaciers The largest and most visible features left by continental glaciers are rock basin lakes in which the former glacier has dug channels or large depressions in which water has collected. Aerial photos of these lakes show how they often follow bedrock fractures or layers of softer rocks that were eroded by the former glaciers. Landscapes with rock basin lakes and rounded hills are called rock knob topography. Features Left by Continental Glaciers Near their origins, continental glaciers are thick and powerful, eroding soils and many rocks, creating bedrock plains. At the edges of former continental glaciers are arc-like remains of rock and soil that were scoured from the bedrock by the glacier and formed the terminal moraine or debris material. Glaciation and Terminal Moraines Gravel deposits (hills of terminal moraine) are found in many locations which continental glaciers left behind. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Glacial till is unsorted debris dropped by a glacier as it melted. It consists of boulders, rocks, gravel, sand and clay. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Rivers and streams from glaciers deposit outwash materials in layers with the heaviest and largest at the bottom and progressively lighter and smaller particles in higher layers. Seasonal changes in the glacier stream velocity produce outwash patterns of alternating coarse and fine sediments. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Glacial erratics are rocks and boulders that have been carried and deposited by glaciers to distant locations. Canadian shield rocks have been carried to southern Ontario and the Praries. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Moraines are hills of debris pushed up in front of or at the bottom of a glacier as it advances. These debris hills will be made up of unsorted glacial till. Moraines forming during halts as a glacier is retreating are called recessional moraines. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Kettles are depressions formed when ice blocks trapped beneath till materials melt. If they fill with water, kettles are called kettle lakes. The name, pitted outwash plain is used when kettle lakes are common in the glacier outwash plain of debris. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Drumlins are streamlined, tear-shaped hills of debris with rounded front ends (stoss) and a longer tapering tail. These form when glaciers re-advance over existing moraine and form these tear-shaped structures. The tails of drumlins point in the direction of the glacier readvance motion. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers A roche moutannee should not be confused with a drumlin. A roche moutannee also has a rounded tear shape but it is made of solid rock and the “tail” of a roche moutannee is pointing in the direction that the glacier came from, the opposite way that a drumlin tail points. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers When glacial streams empty into glacial lakes, they produce extensive sand plains (like the Norfolk Sand Plain in Ontario). If the waters are calm over long periods, clay plains are created as clay settles out of the calmer waters. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Glacier meltwater streams full of sediments may erode the landscape forming wide shallow valleys called spillways (number 1 in diagram). Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Eskers are snake-like ridges of sorted sands, gravels and boulders that were formed by glacial meltwater streams, heavy with sediments, flowing on, in or beneath glacial ice that deposited their sediments as they slowed, in ridges. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Kames are small conical hills of sorted sands and gravels that are the remains of deltas that formed where glacial meltwater streams emptied into ponds or lakes. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Continental glaciers are important to humans because they have provided the gravel deposits which are used in road and home building projects and for making concrete. As these gravel deposits are used, features like eskers, kames and spillway deposits disappear from the landscape. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers Perhaps the most important contribution of continental glaciers for humanity is the rich, fertile soils they left behind. Glacial loess soils formed away from the edges of glaciers through the action of winds. As continental glaciers retreated, their meltwater streams deposited sorted layers of sediments with sand, silt and clay at their surfaces. As these dried, winds picked them up and deposited them many hundreds of km south of the glaciers to form fertile soils. The most productive agricultural regions of the world are on loess soils, many of them glacial loess soils. Land Features Associated With Continental Glaciers European loess soils are found in various regions including the Ukraine region and Russia. End of Presentation A A