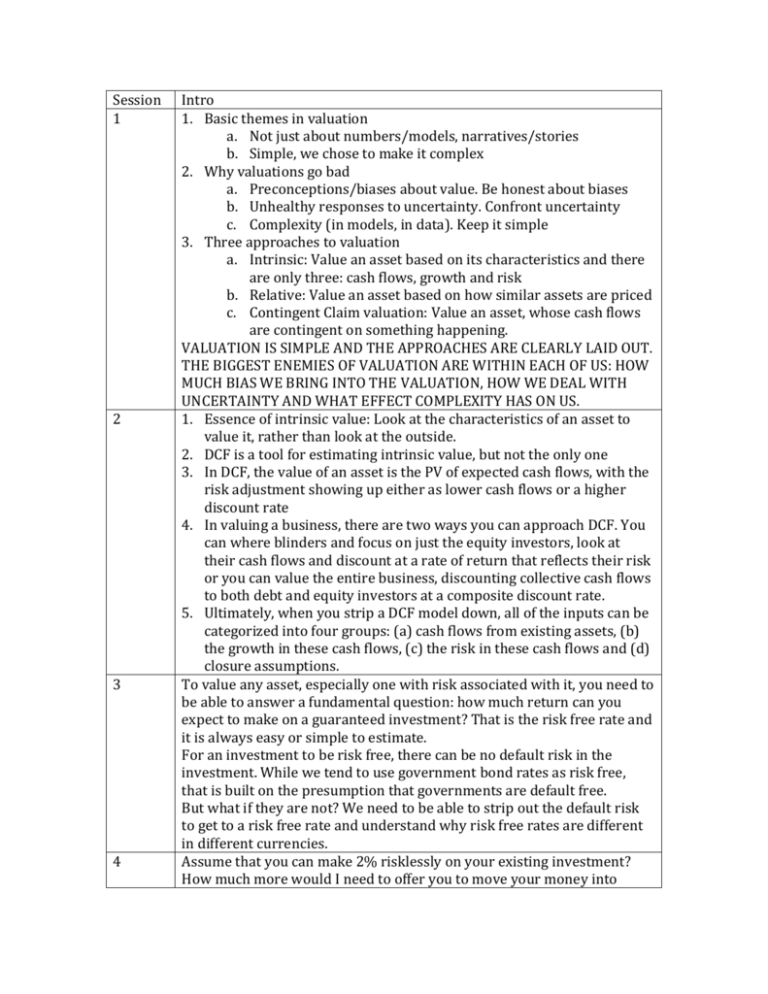

Intros to the sessions - NYU Stern School of Business

advertisement

Session 1 2 3 4 Intro 1. Basic themes in valuation a. Not just about numbers/models, narratives/stories b. Simple, we chose to make it complex 2. Why valuations go bad a. Preconceptions/biases about value. Be honest about biases b. Unhealthy responses to uncertainty. Confront uncertainty c. Complexity (in models, in data). Keep it simple 3. Three approaches to valuation a. Intrinsic: Value an asset based on its characteristics and there are only three: cash flows, growth and risk b. Relative: Value an asset based on how similar assets are priced c. Contingent Claim valuation: Value an asset, whose cash flows are contingent on something happening. VALUATION IS SIMPLE AND THE APPROACHES ARE CLEARLY LAID OUT. THE BIGGEST ENEMIES OF VALUATION ARE WITHIN EACH OF US: HOW MUCH BIAS WE BRING INTO THE VALUATION, HOW WE DEAL WITH UNCERTAINTY AND WHAT EFFECT COMPLEXITY HAS ON US. 1. Essence of intrinsic value: Look at the characteristics of an asset to value it, rather than look at the outside. 2. DCF is a tool for estimating intrinsic value, but not the only one 3. In DCF, the value of an asset is the PV of expected cash flows, with the risk adjustment showing up either as lower cash flows or a higher discount rate 4. In valuing a business, there are two ways you can approach DCF. You can where blinders and focus on just the equity investors, look at their cash flows and discount at a rate of return that reflects their risk or you can value the entire business, discounting collective cash flows to both debt and equity investors at a composite discount rate. 5. Ultimately, when you strip a DCF model down, all of the inputs can be categorized into four groups: (a) cash flows from existing assets, (b) the growth in these cash flows, (c) the risk in these cash flows and (d) closure assumptions. To value any asset, especially one with risk associated with it, you need to be able to answer a fundamental question: how much return can you expect to make on a guaranteed investment? That is the risk free rate and it is always easy or simple to estimate. For an investment to be risk free, there can be no default risk in the investment. While we tend to use government bond rates as risk free, that is built on the presumption that governments are default free. But what if they are not? We need to be able to strip out the default risk to get to a risk free rate and understand why risk free rates are different in different currencies. Assume that you can make 2% risklessly on your existing investment? How much more would I need to offer you to move your money into 5 6 7 8 stocks? The answer to that question is the equity risk premium and it will vary among investors, because they have different risk aversion, and across time, because the risk you see in equities will change over time. Estimating this time varying ERP is a challenge. Some people use historical premiums, but stock returns are very “noisy”. You need a forward looking, dynamic number that changes as the market changes and you also need a way of extending the approach to younger, emerging markets where there may not be much historical data. Ultimately, if you use too low or too high an ERP, you are going to bias your valuations. Assume that you have a risk free rate and have estimated what you would demand as a premium for an average risk investment. To value a risky asset, you now need to make one final extension and estimate how risky that asset is relative to the average. That is the role played by beta. While modern portfolio theory argues for a beta estimated by looking at how an asset (stock) moves with the market, thinking of beta in statistical terms misses the mark. If you truly dislike beta, there are alternative approaches that are based upon accounting numbers or even qualitative judgments that can take that place. Risk free rate, ERP and beta all feed into an estimate of “cost of equity”, i.e, what it costs you to raise equity to finance a business. The other source of financing is debt and there are two questions that you need to address: (a) What is debt? First, not everything that accountants classify as liabilities is debt. Second, not everything that is debt shows up as a liability on the balance sheet (b) The cost of debt is not the rate at which you borrowed money in the past. Once you have a cost of debt, you can then bring it together with the cost of equity and the ‘appropriate” weights to get to a cost of capital, which is the overall cost of funding the business. While analysts spend the bulk of the time estimating and finessing discount rates, they miss a key truth, which is that the big mistakes in valuation are on the cash flows, not the discount rates. Estimating cash flows is a four step process, starting with fine tuning earnings to make sure that they measure what they are supposed to, netting out the right amount in taxes, subtracting out what you need to reinvest to grow and if you are estimating cash flows to equity investors, incorporating the cash flows to or from debt. When estimating cash flows for last year, you have a crutch of accounting statements. When estimating growth for the future, you should start getting uncomfortable because I am asking you to play God. There are generically three ways of estimating growth. One is to look at past growth and extrapolate. The second is to outsource the estimate and use those made by analysts and managers. The third is to tie the growth estimate to fundamentals of the firm: how much and how well it reinvests. If you are doing intrinsic valuation, I see the third way as the most consistent.