The Economics of Banking

advertisement

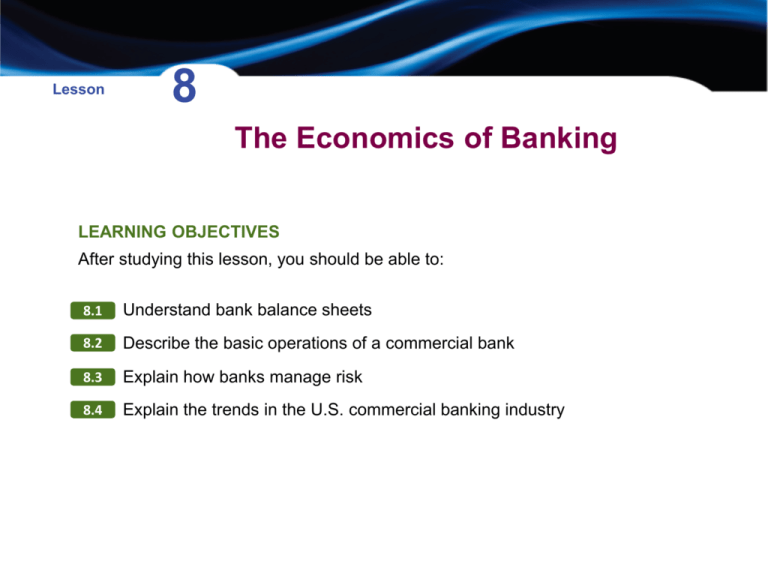

Lesson 8 The Economics of Banking LEARNING OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you should be able to: 8.1 Understand bank balance sheets 8.2 Describe the basic operations of a commercial bank 8.3 Explain how banks manage risk 8.4 Explain the trends in the U.S. commercial banking industry CHAPTER 8 The Economics of Banking WHAT HAPPENS WHEN LOCAL BANKS STOP LOANING MONEY? • In the recovery from the financial crisis of 2007–2009, banks had become extremely cautious in making loans. • Banks were turning away borrowers with flawed credit histories and avoiding industries that were hard hit by the recession. • As the value of real estate declined, the collateral that small businesses could use to borrow against also declined. Key Issue and Question Issue: During and immediately following the 2007–2009 financial crisis, there was a sharp increase in the number of bank failures. Question: Is banking a particularly risky business? If so, what types of risks do banks face? 8.1 Learning Objective Understand bank balance sheets. • The key commercial banking activities are taking in deposits from savers and making loans to households and firms. • A bank’s primary sources of funds are deposits, and primary uses of funds are loans, which are summarized in the bank’s balance sheet. Balance sheet A statement that shows an individual’s or a firm’s financial position on a particular day. • The typical layout of a balance sheet is based on the following accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ equity. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Asset Something of value that an individual or a firm owns; in particular, a financial claim. Liability Something that an individual or a firm owes, particularly a financial claim on an individual or a firm. Bank capital The difference between the value of a bank’s assets and the value of its liabilities; also called shareholders’ equity. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Bank Liabilities Checkable Deposits Checkable deposits Accounts against which depositors can write checks, also called transaction deposits. • Demand deposits are checkable deposits on which banks do not pay interest. • NOW (negotiable order of withdrawal) accounts are checking accounts that pay interest. • Checkable deposits are liabilities to banks and assets to households and firms. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Nontransaction Deposits • The most important types of nontransaction deposits are savings accounts, money market deposit accounts (MMDAs), and time deposits, or certificates of deposit (CDs). • Checkable deposits and small-denomination time deposits are covered by federal deposit insurance. • CDs of less than $100,000 are called small-denomination time deposits. CDs of $100,000 or more are called large-denomination time deposits. CDs worth $100,000 or more are negotiable, which means that investors can buy and sell them in secondary markets prior to maturity. Federal deposit insurance A government guarantee of deposit account balances up to $250,000. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Borrowings • Banks often make more loans than they can finance with funds they attract from depositors. • Bank borrowings include short-term loans in the federal funds market, loans from a bank’s foreign branches or other subsidiaries or affiliates, repurchase agreements, and discount loans from the Federal Reserve System. • Although the name indicates that government money is involved, the loans in the federal funds market involve the banks’ own funds. The interest rate on these interbank loans is called the federal funds rate. • With repurchase agreements—otherwise known as “repos,” or RPs—banks sell securities, such as Treasury bills, and agree to repurchase them, typically the next day. Repos are typically between large banks or corporations, so the degree of counterparty risk is small. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Making the Connection The Incredible Shrinking Checking Account Households hold less in checking accounts relative to other financial assets than they once did, partly due to the wealth effect. As wealth has increased over time, households have been better able to afford to hold assets, such as CDs, where their money is tied up for a while but on which they earn a higher rate of interest. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Bank Assets Bank assets are acquired by banks with the funds they receive from depositors, with funds they borrow, with funds they acquired initially from their shareholders, and with profits they retain from their operations. Reserves and Other Cash Assets Reserves A bank asset consisting of vault cash plus bank deposits with the Federal Reserve. Vault cash Cash on hand in a bank; includes currency in ATMs and deposits with other banks. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Required reserves Reserves the Fed requires banks to hold against demand deposit and NOW account balances. Excess reserves Any reserves banks hold above those necessary to meet reserve requirements. • Excess reserves can provide an important source of liquidity to banks, and during the financial crisis, bank holdings of excess reserves soared. • Another important cash asset is claims banks have on other banks for uncollected funds, which is called cash items in the process of collection. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Securities • Marketable securities are liquid assets that banks trade in financial markets. • Banks are allowed to hold securities issued by the U.S. Treasury and other government agencies, corporate bonds that received investment-grade ratings when they were first issued, and some limited amounts of municipal bonds, which are bonds issued by state and local governments. • Because of their liquidity, bank holdings of U.S. Treasury securities are sometimes called secondary reserves. • In the United States, commercial banks cannot invest checkable deposits in corporate bonds or common stock. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Loans • The largest category of bank assets is loans. Loans are illiquid relative to marketable securities and entail greater default risk and higher information costs. • There are three categories of loans: (1) loans to businesses—called commercial and industrial, or C&I, loans; (2) consumer loans, made to households primarily to buy automobiles, furniture, and other goods; and (3) real estate loans, including both residential and commercial mortgages. • The development of the commercial paper market in the 1980s meant that banks also lost to that market many of the businesses that had been using short-term C&I loans. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Figure 8.1 Loans The Changing Mix of Bank Loans, 1973–2010 The types of loans granted by banks have changed significantly since the early 1970s. Real estate loans have grown from less than one-third of bank loans in 1973 to two-thirds of bank loans in 2010. Commercial and industrial (C&I) loans have fallen from more than 40% of bank loans to less than 20%. Consumer loans have fallen from more than 27% of all loans to about 20%. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Other Assets Other assets include banks’ physical assets, such as computer equipment and buildings. This category also includes collateral received from borrowers who have defaulted on loans. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Bank Capital • Bank capital, also called shareholders’ equity, or bank net worth, is the difference between the value of a bank’s assets and the value of its liabilities. • In 2010, for the U.S. banking system as a whole, bank capital was about 12% of bank assets. • A bank’s capital equals the funds contributed by the bank’s shareholders through their purchases of stock the bank has issued plus accumulated retained profits. • Note that as the value of a bank’s assets or liabilities changes, so does the value of the bank’s capital. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Solved Problem 8.1 Constructing a Bank Balance Sheet The following entries are from the actual balance sheet of a U.S. bank as of December 31, 2009. a. Use the entries to construct a balance sheet similar to the one in Table 10.1, with assets on the left side of the balance sheet and liabilities and bank capital on the right side. b. The bank’s capital is what percentage of its assets? The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Solved Problem 8.1 Constructing a Bank Balance Sheet Solving the Problem Step 1 Review the lesson material. Step 2 Answer part (a) by using the entries to construct the bank’s balance sheet, remembering that bank capital is equal to the value of assets minus the value of liabilities. The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet Solved Problem 8.1 Constructing a Bank Balance Sheet Step 3 Answer part (b) by calculating the bank’s capital as a percentage of its assets. Total assets = $2,223 billion Bank capital = $231 billion Bank capital as a percentage of assets $231 = = 0.104, or 10.4% $2,223 The Basics of Commercial Banking: The Bank Balance Sheet 8.2 Learning Objective Describe the basic operations of a commercial bank. T-account An accounting tool used to show changes in balance sheet items. The T-accounts below show what happens when you open a checking account with $100 at Wells Fargo. In this example, Wells Fargo uses its excess reserves to buy Treasury bills worth $30 and make a loan worth $60. The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank Making the Connection The Not-So-Simple Relationship between Loan Losses and Bank Profits • During the term of the loan, if the bank decides that the borrower is likely to default, the bank must write down or write off the loan. • Banks set aside part of their capital as a loan loss reserve to anticipate future loan losses and avoid large swings in its reported profits and capital from write-offs. • During the financial crisis of 2007–2009, banks set aside enormous loan loss reserves as they anticipated write-downs on mortgage-related loans. • The SEC has argued that banks will sometimes increase their loan loss reserves more than is justified during an economic expansion, when defaults are relatively rare. The banks can then draw down the reserves during a recession, evening out their reported profits. • If true, this practice would amount to “earnings management,” which is prohibited under accounting rules because it may give a misleading view of the firm’s profits. The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank Bank Capital and Bank Profits Net interest margin The difference between the interest a bank receives on its securities and loans and the interest it pays on deposits and debt, divided by the total value of its earning assets. • An expression for the bank’s total profits earned per dollar of assets is called return on assets. Return on assets (ROA) The ratio of the value of a bank’s after-tax profit to the value of its assets. After−tax profit ROA = Bank assets The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank • To judge how a bank’s managers are able to earn on the shareholder’s investment, we use the return on equity. Return on equity (ROE) The ratio of the value of a bank’s after-tax profit to the value of its capital. ROE = After−tax profit Bank capital • ROA and ROE are related by the ratio of a bank’s assets to its capital: ROE = ROA × Bank assets Bank capital The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank • Managers of banks and other financial firms may have an incentive to hold a high ratio of assets to capital. • The ratio of assets to capital is one measure of bank leverage, the inverse of which (capital to assets) is called a bank’s leverage ratio. Leverage A measure of how much debt an investor assumes in making an investment. Bank leverage The ratio of the value of a bank’s assets to the value of its capital, the inverse of which (capital to assets) is called a bank’s leverage ratio. • A high ratio of assets to capital—high leverage—is a two-edged sword: Leverage can magnify relatively small ROAs into large ROEs, but it can do the same for losses. The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank • Moral hazard can contribute to high bank leverage. • If managers are compensated for a high ROE, they may take on more risk than shareholders would prefer. • Federal deposit insurance has increased moral hazard by reducing the incentive depositors have to monitor the behavior of bank managers. • To deal with this risk, government regulations called capital requirements have placed limits on the value of the assets commercial banks can acquire relative to their capital. The Basic Operations of a Commercial Bank 8.3 Learning Objective Explain how banks manage risk. Managing Liquidity Risk Liquidity risk The possibility that a bank may not be able to meet its cash needs by selling assets or raising funds at a reasonable cost. • Banks reduce liquidity risk through strategies of asset management and liquidity management. • Asset management involves lending funds in the federal funds market, usually for one day at a time. • A second option is to use reverse repurchase agreements, which involve a bank buying Treasury securities owned by a business or another bank while at the same time agreeing to sell the securities back at a later date, often the next morning. These very short term loans can be used to meet deposit withdrawals. • Liability management involves determining the best mix of borrowings from other banks or businesses using repurchase agreements or from the Fed by taking out discount loans. Managing Bank Risk Managing Credit Risk Credit risk The risk that borrowers might default on their loans. Diversification • By diversifying, banks can reduce the credit risk associated with lending too much to a single borrower, region, or industry. Credit-Risk Analysis Credit-risk analysis The process that bank loan officers use to screen loan applicants. • Banks often use credit-scoring systems to predict whether a borrower is likely to default. Historically, the high-quality borrowers paid the prime rate. Today, most banks charge rates that reflect changing market interest rates instead of the prime rate. Prime rate Formerly, the interest rate banks charged on six-month loans to highquality borrowers; currently, an interest rate banks charge primarily to smaller borrowers. Managing Bank Risk Collateral • Collateral, or assets pledged to the bank in the event that the borrower defaults, is used to reduce adverse selection. • A compensating balance is a required minimum amount that the business taking out the loan must maintain in a checking account with the lending bank. Credit Rationing Credit rationing The restriction of credit by lenders such that borrowers cannot obtain the funds they desire at the given interest rate. • Loan and credit limits reduce moral hazard by increasing the chance a borrower will repay. • If the bank cannot distinguish the low- from the high-risk borrowers, high interest rates risk dropping the low-risk borrowers out of the loan pool, leaving only the high-risk borrowers—a case of adverse selection. Managing Bank Risk Monitoring and Restrictive Covenants • Banks keep track of whether borrowers are obeying restrictive covenants, or explicit provisions in the loan agreement that prohibit the borrower from engaging in certain activities. Long-Term Business Relationships • The ability of banks to assess credit risks on the basis of private information on borrowers is called relationship banking. • By observing the borrower, the bank can reduce problems of asymmetric information. Good borrowers can obtain credit at a lower interest rate or with fewer restrictions. Managing Bank Risk Managing Interest-Rate Risk Interest-rate risk The effect of a change in market interest rates on a bank’s profit or capital. A rise (fall) in the market interest rate will lower (increase) the present value of a bank’s assets and liabilities. Managing Bank Risk Measuring Interest-Rate Risk: Gap Analysis and Duration Analysis Gap analysis An analysis of the difference, or gap, between the dollar value of a bank’s variable-rate assets and the dollar value of its variable-rate liabilities. • Gap analysis is used to calculate the vulnerability of a bank’s profits to changes in market interest rates. • Most banks have negative gaps because their liabilities—mainly deposits—are more likely to have variable rates than are their assets—mainly loans and securities. Managing Bank Risk Duration analysis An analysis of how sensitive a bank’s capital is to changes in market interest rates. • If a bank has a positive duration gap, the duration of the bank’s assets is greater than the duration of the bank’s liabilities. In this case, an increase in market interest rates will reduce the value of the bank’s assets more than the value of the bank’s liabilities, which will decrease the bank’s capital. Managing Bank Risk Reducing Interest-Rate Risk • Banks with negative gaps can make more adjustable-rate or floating-rate loans. That way, if market interest rates rise and banks must pay higher interest rates on deposits, they will also receive higher interest rates on their loans. • Banks can use interest-rate swaps in which they agree to exchange, or swap, the payments from a fixed-rate loan for the payments on an adjustable-rate loan owned by a corporation or another financial firm. • Banks have available to them futures contracts and options contracts that can help hedge interest-rate risk. Managing Bank Risk 8.4 Learning Objective Explain the trends in the U.S. commercial banking industry. The Early History of U.S. Banking The National Banking Act of 1863 made it possible for a bank to obtain a federal charter. National bank A federally chartered bank. Dual banking system The system in the United States in which banks are chartered by either a state government or the federal government. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Bank Panics, the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation • The Federal Reserve plays the role of a lender of last resort by making discount loans to banks suffering from temporary liquidity problems. • Before the Fed existed, banks were subject to bank runs. • If many banks simultaneously experienced runs, the result would be a bank panic, which often resulted in banks being unable to return depositors’ money and having to temporarily close their doors. • Bank panics typically resulted in recessions. After the severe bank panic of 1907, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. • The Great Depression led to bank panics, and Congress responded with the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), established in 1934. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Figure 8.2 Commercial Bank Failures in the United States, 1980–2010 Bank failures in the United States were at low levels from 1960 until the savings and loan crisis of the mid-1980s. By the mid-1990s, bank failures had returned to low levels, where they remained until the beginning of the financial crisis in 2007. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry The Rise of Nationwide Banking • In the early 1900s, banks were prohibited from crossing state lines. Unit banking meant that banks were kept small, serving the local area. • In 1900, of the 12,427 commercial banks in the United States, only 87 had any branches. • The U.S. system of many small, geographically limited banks failed to take advantage of economies of scale in banking. • Restrictions on branching within the state loosened after the mid-1970s, and in 1994, Congress passed the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, which allowed for the phased removal of restrictions on interstate banking. • These changes led to rapid consolidation of banks, from 14,384 in 1975 to only 6,839 by 2009. In 2010, concerns about bank size and banks “too big to fail” were discussed in Congress, but no limits on size were finally enacted. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Expanding the Boundaries of Banking • Between 1960 and 2010, banks increased their funds and borrowings; they relied less on C&I and consumer loans, and more on real estate loans; they expanded into nontraditional lending activities and activities generating revenue from fees instead of interest. Off-Balance-Sheet Activities Off-balance-sheet activities Activities that do not affect a bank’s balance sheet because they do not increase either the bank’s assets or its liabilities. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Off-Balance-Sheet Activities Four important off-balance-sheet activities that banks have come to rely on to earn fee income include: 1. Standby letters of credit. Standby letter of credit A promise by a bank to lend funds, if necessary, to a seller of commercial paper at the time that the commercial paper matures. 2. Loan commitments. Loan commitment An agreement by a bank to provide a borrower with a stated amount of funds during some specified period of time. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Off-Balance-Sheet Activities Four important off-balance-sheet activities that banks have come to rely on to earn fee income include: 3. Loan sales. Loan sale A financial contract in which a bank agrees to sell the expected future returns from an underlying bank loan to a third party. 4. Trading activities. • Banks earn fees from trading in the multibillion-dollar markets for futures, options, and interest-rate swaps. • Bank losses from trading in securities became a concern during the financial crisis of 2007-2009. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Electronic Banking • The first important development in electronic banking was the spread of automatic teller machines (ATMs). • By the mid-1990s, virtual banks, or banks that carry out all their banking activities online, began to appear. • By the mid-2000s, most traditional banks had also begun providing online services. • Check clearing is now done electronically. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Making the Connection Can Electronic Banking Save Somalia’s Economy? • For a market economy to function, a government needs to maintain a minimum level of order. • Banks are particularly vulnerable to robberies. Not surprisingly, brick-andmortar banks are scarce in Somalia, which has been subjected to incessant civil wars and rampant violence. • But for the past three years, Somali GDP has been growing, and entrepreneurs have realized that they can provide virtual banking services through cell phones and Internet access. • Somalis are now able to keep deposits online, transfer money, and obtain credit. • While electronic banking appears to have contributed to the welcome economic progress, the country’s other problems present significant obstacles to maintaining that growth. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry The Financial Crisis, TARP, and Partial Government Ownership of Banks • As the financial crisis unfolded, residential real estate mortgages began to decline in value. • The market for mortgage-backed securities froze, meaning that buying and selling of these securities largely stopped, making it very difficult to determine their market prices. These securities became known as “toxic assets.” • Evaluating balance sheets and determining the true value of bank capital was difficult. • Banks responded to their worsening balance sheets by tightening credit standards for consumer and commercial loans. The resulting credit crunch helped bring on the recession that started in December 2007, as households and firms had increased difficulty funding their spending. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) A government program under which the U.S. Treasury purchased stock in hundreds of banks to increase the banks’ capital. Another initiative to inject capital into banks, called the Capital Purchase Program (CPP), also relied on the U.S. Treasury to purchase stock in hundreds of troubled banks. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Making the Connection Small Businesses: Key Victims of the Credit Crunch • Small businesses play a key role in the economy. Businesses with fewer than 500 employees generate most of the jobs in the economy. • During the financial crisis, banks were building their reserves and tightening lending requirements, so it became increasingly difficult for small firms to fund their operations. • As commercial real estate values declined, borrowing against the value of stores or factories became more difficult. • Banks worried that the severity of the recession would increase adverse selection and moral hazard. Pressure from government regulators to avoid making risky loans and credit limits on credit cards also limited the borrowing ability of small businesses. • The large employment losses during the recession came in part from the difficulty of small businesses to obtain loans. Trends in the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry Answering the Key Question At the beginning of this lesson, we asked the question: “Is banking a particularly risky business? If so, what types of risks do banks face?” In a market system, businesses of all types face risks, and many fail. Economists and policymakers are particularly concerned about the risk and potential for failure that banks face because they play a vital role in the financial system. In this lesson, we have seen that the basic business of commercial banking—borrowing money short term from depositors and lending it long term to households and firms—entails several types of risks: liquidity risk, credit risk, and interest-rate risk. AN INSIDE LOOK AT POLICY Interest-Rate Hikes Threaten Bank Profits REUTERS, U.S. Regulators Warn Banks on Interest Rate Risk Key Points in the Article • In early 2010, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) urged commercial banks to protect themselves against a likely increase in interest rates. • Banks had profited by borrowing funds at low rates and purchasing assets such as Treasury securities that had higher yields. • Some institutions are expecting interest rates to remain at historic lows, but it is unlikely that the Fed will keep rates near zero forever. • As interest rates rise, banks relying heavily on short-term funds could see their funding costs accelerate. Longer-term assets may no longer be profitable to own, forcing banks to sell securities en masse and potentially weakening the financial sector again. AN INSIDE LOOK AT POLICY Evidence of U.S. banks’ profits can be found in their balance sheets. Bank capital as a percentage of assets was lower when interest rates were higher prior to the financial crisis.