Comprehensive Cardiometabolic Risk

advertisement

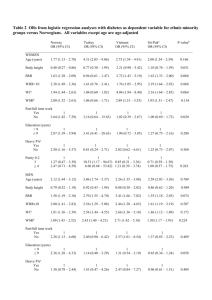

Comprehensive Cardiometabolic Risk-Reduction Program Phase 2 2009 Sponsored by National Lipid Association Case Study Special Considerations for the Overweight/Obese Patient Case Study Overview • A 46-year-old male lawyer is referred by his physician for persistent weight gain and high cardiomyopathy risk • Patient has hyperlipidemia and hypertension; comorbidities include asthma, attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), chronic fatigue, and depression • Family history of obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes • Current weight of 305.7 pounds is his highest – Admits poor nutritional habits and a low activity level • Reports waking up “snorting” from snoring at night – Experiences morning headaches and daytime somnolence The Regulation of Food Intake Is a Complex Process Brain Central Signals Stimulate NPY AGRP Galanin Orexin-A Dynorphin Peripheral Signals Glucose – CCK, GLP-1, Apo A-IV Vagal afferents + Insulin Ghrelin – + Inhibit a-MSH CRH/UCN GLP-I CART NE 5-HT External Factors Emotions Food characteristics Lifestyle behaviors Environmental cues Peripheral Organs Gastrointestinal tract Food Intake Adipose tissue Leptin Cortisol Adrenal glands Zhang Y, et al. Nature. 1994;372:425-432; Schwartz MW, et al. Nature. 2000;404:661-671. NPY=neuropeptide Y, AGRP=agouti-related protein, α-MSH=alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, CRH/UCN=corticotropin-releasing hormone/urocortin, GLP-1=glucagon-like peptide-1, CART=cocaine- and amphetamineregulated transcript, NE=norepinephrine, 5-HT= seratonin, CCK=cholecystokinin, Apo A-IV= apolipoprotein A-IV. Case Study Overview • Medications – – – – – – Metoprolol 100-mg BID Atorvastatin 10-mg QD Niacin 1500-mg BID Paroxetine 40-mg QD Lithium 900-mg QD Amphetamine/ dextroamphetamine 40-mg QD Starting Your Investigation • Look for – – – – Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) Medications causing weight-gain Depression Metabolic syndrome, prediabetes The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. October 2000. NIH Publication No. 00-4084. Clinical Pearl A Vicious Cycle Weight Gain Depression Sleep Apnea Drug-Associated Weight-Change Reference Remember to keep this list in your office! © 2007 Cardiometabolic Support Network Case Study Medications That May Be Contributing to This Patient’s Excess Body Weight MAOIs=monoamine oxidase inhibitors, TCAs=tricyclic antidepressants, ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme Case Study Laboratory Results • Glucose: 106 mg/dL • hs-CRP: 8.2 mg/L=high risk • TC: 184 mg/dL • A1c: 5.9% • HDL-C: 33 mg/dL • Creatinine: 1.2 mg/dL • LDL-C: 103 mg/dL • AST: 27 U/L • TG: 240 mg/dL • ALT: 43 U/L • eGFR: >60 mL/min • Non–HDL-C: 151 mg/dL • EKG: sinus bradycardia, rate 56 TC=total cholesterol, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=triglycerides, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, ALT=alanine aminotranferase, hsCRP=high-sensitivity C-reactive protein Case Study Initial Registered-Dietitian Appointment • Weight: 305.1 pounds, height: 72 inches, BMI: 41.4 kg/m2, waist: 48 inches • Former athlete with low activity level • Volume eater with little sense of satiety “when he gets started” • Daytime fatigue noted, being treated for ADHD • Diet – Little fast food/red meat – Eats before bed and sometimes wakes up in the middle of the night to eat – Breakfast: nothing, lunch: salad, snack: fruit, dinner: Greek salad with chicken or stirfry, snack: “bad” • Plan – Keep food records – Begin to eat breakfast – Eat higher lean-protein lunches and dinners and begin to reduce refined carbohydrates – Goal of 30 minutes of walking/day ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, BMI=body mass index Clinical Pearl High-frequency telephone- and web-based nutritional counseling can be effective ways to help patients lose weight Clinical Pearl Breakfast and Nighttime Eating • Skipping breakfast can drive nighttime eating – – – – Breakfast=none Lunch=breakfast Dinner=lunch Nighttime snack=dinner • Nighttime eating drives skipping breakfast • The cycle continues… ARS Question Which may be the best diet for someone with a lack of satiety? A. Low protein B. Low fat C. Low glycemic Glycemic Index (GI) • Although data vary, a low-GI meal may reduce subsequent energy intake1 • Cochrane systematic review indicates that decreasing the GI* of a diet may be an effective way to promote weight-loss and improve lipid profiles2 *GI=area under the curve (AUC) of the 2-hour blood glucose response curve divided by the AUC of an equal amount of glucose, multiplied by 100 Low GI food/meal = 55 or less 1. Flint A, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1365-73. 2. Thomas DE, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD005105.pub2. Clinical Pearl Diet: What Is Most Important? Calorie restriction, with high macronutrient quality* *High quality indicates more than 5 servings of fruits and vegetables/day, lean protein sources including some vegetarian sources, nuts, healthy oils, nonfat dairy products, whole grains, low in sweets and refined carbohydrates, low in fat Favorable Option for This Patient • Low refined-carbohydrate diet with increased fiber intake – – – – Patient has prediabetes Rapid weight-loss is desirable Patient’s snacks tend to be refined carbohydrates Lower refined-carbohydrates reduce hunger in some patients – Higher fiber associated with satiety • Higher protein intake – Protein increases satiety – Lean protein has little fat and saturated fat, making it a healthy option for weight loss Practical Tips: Increasing Fiber and Lean Protein • Fiber – Fiber One® bran cereal • Sprinkle it on low-fat yogurt as a bedtime snack – Whole grains, fruits, and vegetables • Lean protein – Ham, turkey, and roast beef are the leanest sandwich meats • Have 1/2 sandwich, but double the thickness – Carnation® Instant Breakfast® No Sugar Added with skim milk=inexpensive, low-GI meal replacement – Modified pastas that are no longer “refined carbohydrates” • Barilla® PLUS® (2-cups cooked)=17-g protein, 7-g fiber, 360mg omega-3 fatty acid Case Study Initial MD Appointment • Weight: 305.7 lbs, height: 72 inches, BMI: 41.5 kg/m2, blood pressure: 138/90, heart rate: 68 bpm, waist: 48 inches • Patient is at his highest weight – Several prior weight-loss attempts: no significant progress, has been steadily gaining weight – Admits poor nutritional habits and a low activity level • Reports waking up “snorting” from snoring at night – Has morning headaches and daytime somnolence • Food records show nighttime eating pattern, with large quantities consumed after 6:00 PM Case Study • Medications – – – – – – Metoprolol 100-mg BID Atorvastatin 10-mg QD Niacin 1500-mg BID Paroxetine 40-mg QD Lithium 900-mg QD Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine 40-mg QD • Action plan – – – – Reinforce importance of continued dietitian visits Sleep study to evaluate for obstructive sleep apnea Stop metoprolol; initiate ramipril, titrate ↑ to 5-mg BID Begin metformin ER 500-mg QD, with goal to increase Clinical Pearl What if β-Blockers Are Necessary? If a β-blocker is necessary as part of a multi-agent antihypertensive regimen, an agent that does not aggravate insulin resistance (eg, carvedilol) may be a favorable choice ARS Question According to the 2007 ADA Consensus Statement on impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), which of the following is not true? Metformin is appropriate for use in patients with IFG, IGT, and A. A1c ≥5.0% B. Hypertension C. BMI ≥35 kg/m2 D. Family history of diabetes in first-degree relative ADA=American Diabetes Association, BMI=body mass index Pharmacological Intervention in the Progression to Diabetes: Recent Statements • ADA 2007 Consensus Statement – Metformin as an adjunct/alternative to lifestyle in patients with IFG and IGT, and any of the following • <60 years of age, BMI >35 kg/m2, family history of type 2 diabetes in first-degree relative, ↑ triglycerides, ↓ HDL-C, hypertension, A1C >6.0% • ACE 2008 Consensus Statement – Metformin or acarbose as an adjunct to lifestyle in patients with prediabetes at particularly high risk ADA=American Diabetes Association, IFG=impaired fasting glucose, IGT=impaired glucose tolerance, BMI=body mass index, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, ACE=American College of Endocrinology Nathan DM, et al. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:753-759. American College of Endocrinology Task Force on Pre-Diabetes. Available at: www.aace.com/meetings/consensus/hyperglycemia/hyperglycemia.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2008. Diabetes Prevention Program Don’t Forget: Lifestyle Is More Effective Than Metformin Weight Decrease loss in risk* Cumulative Incidence of Diabetes (%) 40 Placebo 0.1 kg 30 Metformin 20 Lifestyle 10 0 0 1 2 Years 3 4 P<0.001 for each comparison. *Decrease in risk of developing diabetes compared to placebo group. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403. 2.1 kg 31% 5.6 kg 58% Case Study Month 2—MD Visit 2 • Weight: 294.5 lbs, blood pressure: 140/90, heart rate: 64 bpm, waist: 47 inches • Followed diet very strictly for first few weeks – Now on diet ≈70% of the time – Still skips breakfast • Patient rescheduled sleep study, reminded of importance by MD – Reports being very fatigued and realizes he eats to stay awake • Action plan – Increase metformin 500-mg to BID, eat protein breakfast instead of skipping the meal Case Study Sleep-Study Results • Apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 57.8 – Diagnosis: severe obstructive sleep apneahypopnea syndrome • Action plan – Began continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment with 12 cm H20 • Follow-up AHI of 5.0 Clinical Pearl Many patients won’t tolerate CPAP… Risk of erectile dysfunction can be a strong motivator Case Study Month 3—Registered-Dietitian Visit 2 • Weight: 290.6 lbs • Not eating breakfast – “No time, no interest, not hungry” • Eating less at night • Patient hurt his back and is going to physical therapy, but little aerobic activity secondary to fatigue • Seeing new psychiatrist who will evaluate medical regimen • Plan – Meal replacements for breakfast – Continue low-glycemic index diet (increase vegetables, steak only 1x/week) Meal Replacements • Important for patients who have – Little time for food shopping and preparation – Hit a weight plateau – Persistent difficulty managing food and social cues related to overeating • Advantages – Provide adequate and consistent nutrition as a low-fat, calorie-controlled replacement for 1 or 2 meals per day – Eliminate food choices and temptations – Simplify food shopping and preparation – Convenient to carry and store Meal Replacements Promote Short- and Long-Term Weight Loss Phase 1* Phase 2 CF MR-1 Weight Loss (%) 0 5 MR-2 10 15 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 18 Time (mo) 24 *1200–1500 kcal/d diet prescription CF=conventional foods; MR-2=replacements for 2 meals, 2 snacks daily; MR-1=replacements for 1 meal, 1 snack daily Fletchner-Mors, et al. Obes Res. 2000;8:399. 30 36 45 51 Case Study Month 5—MD Visit 3 • Weight: 277.7 lbs (-28 lbs), BMI: 37.7 kg/m2; blood pressure: 130/80, heart rate: 64 bpm, waist: 44 inches • Now on CPAP at 12 cm H20 – Notes that he feels much better, with more energy and focus • Since sleep study and CPAP use, psychiatrist decreased lithium to 600-mg QD, paroxetine to 20-mg QD, and amphetamine/ dextroamphetamine to 20-mg QD DHA/EPA=docosahexaenoic acid/eicosapentaenoic acid Case Study Month 5—MD Visit 3 Lab Results • • • • • • Glucose: 92 mg/dL TC: 176 mg/dL HDL-C: 30 mg/dL LDL-C: 106 mg/dL TG: 200 mg/dL Non–HDL-C: 146 mg/dL • • • • • hs-CRP: 3.1 mg/L A1c: 5.6% Creatinine: 1.2 mg/dL AST: 25 U/L ALT: 40 U/L TC=total cholesterol, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=triglycerides, hsCRP=high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, ALT=alanine aminotranferase ARS Question Which of the following would you be most likely to consider as part of the action plan for this visit? A. Increase statin dosage B. Switch to a different statin C. Add a fibrate D. Discontinue niacin and add omega-3 FAs Case Study Month 5—MD Visit 3 Action plan • Discontinue niacin • Start omega-3 (DHA/EPA) fatty acids (FA) 2000-mg QD, to BID • Increase metformin to 850-mg BID Clinical Pearl Due to the negative effect of niacin on glucose control and insulin resistance1,2, omega-3 fatty acids may be a preferred alternative in patients at risk for diabetes* *Reflects opinion of program Steering Committee. TC=total cholesterol, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=triglycerides, hsCRP=high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, ALT=alanine aminotranferase 1. Vittone F, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:203-210. 2. Goldberg RB, et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008; 83:470-8. Case Study Month 6—Registered-Dietitian Visit 3 • Weight: 274.6 lbs • Patient has been doing well with breakfast meal replacements, but is bored with diet and feels he has hit a weight plateau • Plan – Congratulate him on losing 30 lbs! – Continue low-glycemic index diet, but brainstorm alternative breakfast and snack options – Food records 3 days/week, self-monitor weight every day for next 2 weeks – Reinforce need for physical activity Case Study Month 8—MD Visit 4 • Weight: 270.7 lbs (-35 lbs [-11%]), blood pressure: 124/82, heart rate: 68 bpm, waist: 43 inches • Current meds: atorvastatin 10-mg QD, metformin 850mg BID, omega-3 fatty acids (DHA/EPA) 2000-mg BID, ramipril 5-mg BID, amphetamine/dextroamphetamine 20-mg QD, paroxetine 20-mg QD, lithium 600-mg QD • Using CPAP regularly and has good energy level • Fair compliance to diet secondary to stress/family – Has some night eating, but generally minimizing sugar and carbohydrates • He now feels active enough to exercise and is walking 20 min/day 4x/week Case Study Month 8—MD Visit 4, Laboratory Results • Glucose: 90 mg/dL • TC: 157 mg/dL • HDL-C: 42 mg/dL • LDL-C: 91 mg/dL • TG: 120 mg/dL • Non–HDL-c: 115 mg/dL • A1c: 5.2% • hs-CRP: 1.2 mg/L TC=total cholesterol, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG=triglycerides, hs-CRP=high-sensitivity C-reactive protein Case Study Month 8—MD Visit 4, Action Plan • Psychiatrist stopped lithium, reduced paroxetine to 10-mg QD and reduced amphetamine/dextroamphetamine to 10mg QD • Continue metformin 850-mg BID and use of CPAP • Prescribe exercise regimen Clinical Pearl • In addition to lifestyle factors, biology favors weight regain Eckel RH. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1941-1950. ARS Question According to the US Department of Health and Human Services 2008 guidelines, how many minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise do many people need to maintain their weight after a significant amount of weight loss? A. B. 60 120 C. 180 D. >300 US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx. Accessed February 6, 2009. Clinical Pearl Although caloric restriction is the key to weight loss, regular physical activity is crucial to maintaining a lower body weight National Weight Control Registry: Cardinal Behaviors of Successful Long-Term Weight Management • Self-monitoring – Diet: record food intake daily, limit certain foods or food quantity – Weight: check body weight >1x/week • Low-calorie, low-fat diet – Total energy intake: 1300–1400 kcal/day – Energy intake from fat: 20%–25% • Eat breakfast daily • Regular physical activity: 2500–3000 kcal/week (eg, walk 4 miles/day) Klem, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:239. McGuire, et al. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord.1998;22:572. Key Learnings: Medical • Look for sleep apnea and treat it • Get your patients off drugs that cause obesity (when possible) • Consider insulin sensitizers • Assess medications for aggravation of comorbidities • Ask patients how well they are sticking to their intended lifestyle changes Key Learnings: Behavioral • Adapt the diet to your patient • Inform patients that breakfast is associated with weight loss/lower bodyweight • Encourage self-monitoring – Food records – Regular “weigh-ins” • Reinforce that exercise is critical for the maintenance of weight loss At the initial clinical presentation, would this patient have been a candidate for bariatric surgery? • Weight: 305.7 lbs, BMI: 41.5 kg/m2, waist: 48 inches, blood pressure: 138/90, heart rate: 68 bpm • Patient at his highest weight and gaining – Several weight-loss attempts without significant progress • Hyperlipidemia, hypertension, asthma, attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder, fatigue, depression, obstructive sleep apnea • Family history of obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes Laboratory Test Results • TC: 184 mg/dL • HDL-C: 33 mg/dL • LDL-C: 103 mg/dL • TG: 240 mg/dL BMI=body mass index • • • • Non–HDL-C: Glucose: A1c: hs-CRP: 151 mg/dL 106 mg/dL 5.9% 8.2 mg/L Bariatric Surgery • Indications – BMI >40 kg/m2 or BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2 and lifethreatening cardiopulmonary disease, severe diabetes, or lifestyle impairment – Failure to achieve adequate weight-loss with nonsurgical treatment • Contraindications – History of noncompliance with medical care – Certain psychiatric illnesses: personality disorder, uncontrolled depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse – Unlikely to survive surgery Adapted from www.obesityonline.org. NIH Consensus Development Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956. Clinical Pearl Surgeon experience is the single best predictor of success To locate an ASMBS Center of Excellence http://www.surgicalreview.org/ ASMBS=American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. ARS Question Which of the following is true about the effects of bariatric surgery? A. It has not yet been associated with a significant improvement in overall mortality B. At 10-years postprocedure, it is associated with a decrease in the incidence of hypertension C. At 10-years postprocedure, over 1/3 of patients with diabetes at baseline no longer had the disease Swedish Obese Subjects Study Bariatric Surgery: Long-Term Effects on Weight and Cardiovascular Risk Factors • Prospective, controlled intervention trial of 4047 obese subjects (age=48 years, BMI=41 kg/m2); gastric surgery* vs conventional treatment • At 10 years – Weight change—surgery: 16.1% – Weight change—control: 1.6% (P<0.001) – Lower incidence of diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and hyperuricemia (P<0.05 for each) Rate of Recovery (% of Subjects) 100 † 73 80 † 60 40 Control 53 † 46 † Surgery 48 36 ‡ 24 27 19 13 11 20 0 Hypertriglyceridemia Low HDL Cholesterol Sjostrom L, et al. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683-2693. Diabetes Hypertension Hyperuricemia *Banding, vertical-banded gastroplasty, gastric bypass †P≤0.001 ‡P=0.02 Swedish Obese Subjects Study Bariatric Surgery: Long-Term Weight Loss and Decreased Mortality • Up to 16 years follow-up • Overall mortality – Hazard ratio*=0.76 (95% CI: 0.59–0.99), P=0.04 14 Cumulative Mortality (%) Change in Weight (%) 0 Control 10 Banding -20 Vertical-Banded Gastroplasty Gastric Bypass -30 12 Control 10 8 6 Surgery 4 P=0.04 2 0 0 1 2 3 4 6 8 10 Years *Surgical group vs control group at 16 years Sjostrom L, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-752. 15 0 2 4 6 8 Years 10 12 14 16 Key Learnings: Bariatric Surgery • Advantages – “Forced” lifestyle changes – Improved cardiometabolic risk-factors – Decrease in diabetes • Both recovery and incidence – Decrease in mortality • Pitfalls – Surgical complications – “Forced” lifestyle changes – Patients can “get around” the surgery