Institutional Analysis of Natural Resource Policy Course title and

Institutional Analysis of Natural Resource Policy

Course title and number

Term

Meeting times and

Location

ESSM 689 SPTP- Institutional Analysis of Natural Resource Policy

(3-0). Credit 3

Fall 2015

T & TH, 2:20-3:35 PM

CE203

Short Description

This class provides an introduction to theories of institutional analysis as applied to studying the governance of natural resources. We will learn how rules are made and change, and how they can be analyzed systematically to understand their impacts on the dynamics of collective action around the management of natural resources. The course is built around extensive reading and discussion. In addition, students will work together as a team to conduct research that will serve as the basis for an institutional analysis of a policy problem. As such, the course will also have a laboratory-like component, in that students will learn how to conduct research through the process of doing research.

Course Description and Prerequisites

This course is designed to introduce research oriented graduate students to a set of theories for studying environmental and natural research policy. The core theory taught in this class is called institutional analysis, and it draws on political economic research traditions as they have developed over the last half of a century in the fields of political science and economics, although with significant influence from the other social sciences. Emphasis will be placed on what is sometimes called the “Workshop,” “Indiana,” or “Bloomington” school of thought, after the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University in Bloomington, where many of the core ideas and methods were developed by Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues.

Institutional Analysis places the problem of collective action at the core of understanding human societies, and their interactions with ecosystems: How can individuals work together in groups, communities, or larger polities to govern themselves and solve problems? Institutional Analysis posits that institutions are the core means by which groups of people solve collective action problems, and thus the core means by which environmental problems are created (and can be solved). Institutions act by providing incentives to individuals to behave in certain ways, and thus understanding individuals, and how they react to incentives, is crucial to understanding how institutions influence collective action and ultimately affect the environment. Institutional analysis provides a set of conceptual tools for analyzing these problems, and although the focus in this class is on understanding environmental policy, these same conceptual tools can be utilized to understand a broad array of policy problems.

In this course we will study the core literature of institutional analysis, along with influential related literature, and examine a selection of important uses of institutional analysis as they relate to environmental policy. In order to deepen our understanding of the application of institutional analysis, we will work together on a team project in which we attempt to apply institutional analysis to a policy problem of our own choosing.

This course is designed as an introduction to a complex field. In order to emphasize those aspects of institutional analysis that are most directly relevant to the analysis of environmental policy problems, other elements have been deemphasized. A wide variety of methods are utilized in institutional analysis, and students who wish to gain a deeper understanding of these methods are encouraged to consider other coursework in social science research methods, game theory, and political processes, among other subjects.

Prerequisites: Graduate Standing or approval of instructor. Students lacking a background in political science & economics should check with the instructor for recommended supplemental readings.

Learning Outcomes or Course Objectives

1.

Students will be able to apply the conceptual tools of institutional analysis to the analysis of environmental problems.

2.

Students will be able to design research that advances the field of institutional analysis.

3.

Students will improve their ability to present social scientific research in a professional manner and act as colleagues in an interdisciplinary setting.

Instructor Information

Name: Dr. Forrest Fleischman

Telephone number: 979-862-1071 Office (please note that email is preferred)

Email address:

Office hours:

Office location: forrestf@tamu.edu

Weds 2-4 pm, Thursday 3:35-5 pm

310 HFSB

Assessment, Grading & Course Structure

The first assessment is a weekly memo to be written as a reflection on the week’s readings, and due each week on Tuesday at 9 AM (i.e. the morning before the first class of the week) except for the first week of the class, when the memo will be due Thursday, September 3, at 9 AM.

Some weeks a specific assignment will be given, while for other weeks, students will be asked to reflect more independently on the week’s readings. Students should complete reading responses for each of the 12 weeks which have assigned readings. Only the highest 10 grades will count towards the final grade (allowing students to drop their lowest 2 memo grades).

Collectively, this accounts for 30% of the final grade.

The second assessment is participation in class, which will account for 20% of the final grade.

Students are required to meaningfully participate in every session of the class by engaging in discussion of the assigned readings and developing project work. Students are expected to come to class with questions and/or thoughts to share with the class, engage critically and positively with their peers, and attend the class regularly. Interim participation grades will be shared with students after week 4 and week 8.

The third form of assessment will be a group assignment. As a class, we will conduct an institutional analysis of an environmental problem in Texas. We will work together to collectively conduct research and analyze our findings. Students will be evaluated based on their individual contribution to this project, as well as on the final outcome of the project as a whole. Four elements are required:

Project proposal (worth 100 points)

Interim Field work report (worth 100 points)

Rough draft (worth 100 points)

Final Draft (worth 200 points)

Grading Policies

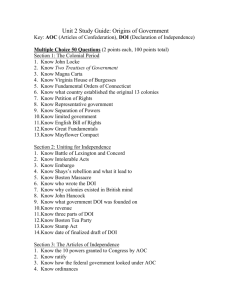

The points in the course will be assigned as follows

Number of

Points Assignment

Weekly reading responses/reflections (10 worth 30 points each) 300

200

500

In class participation

Final Project

Grading Scale:

900-1000 = A

800-899 = B

700-799 = C

600-699 = D

Below 599 = F

Attendance and Late Work Policy

Students are expected to attend class regularly, participate actively in in-class activities, including both full-class discussions and small-group project work, and submit assignments on time. Students who do not attend class regularly, or who attend but do not actively participate, will be penalized directly, through their in-class participation grade, as well as indirectly, through their limited ability to complete other assignments.

Prompt completion of work in this class is important. Students who hand in assignments after the time it is due will receive 50% credit for the assignment if completed and handed in within

24 hours of the due date, after which it will receive a zero. Please note the statement above, which indicates that some memos can be dropped. Late work will be accepted in the case of a

University Excused Absence with no penalty. There will be no makeup for missed exams, except in the case of an University Excused Absence. The University views class attendance as the responsibility of an individual student. Attendance is essential to complete the course successfully. University rules related to excused and unexcused absences are located on-line at http://student-rules.tamu.edu/rule07 . I will grant extensions in situations not covered by university rules only in extenuating circumstances, and only if you contact me before the due date for the assignment.

Textbook and/or Resource/Reading Material

The following texts are required for the course. All except for Ostrom (1990) are available as electronic books – and can be found through the University library catalog or in the electronic course reserves system: http://library-reserves.tamu.edu/areslocal/index.htm

. Ostrom (1990) is available as a print reserve at the West Campus Library. Most other readings are available through Texas A&M online library resources. When they are not available through library resources, they will be available through the class eCampus page.

1.

Steinberg, P. F. (2015). Who Rules the Earth? How Social Rules Shape Our Planet and

Our Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for

Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

3.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance .

New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

4.

Poteete, A. R., Janssen, M., & Ostrom, E. (2010). Working together : collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press.

5.

Sabatier, P. A., & Weible, C. M. (2014). Theories of the Policy Process . New York:

Westview Press.

6.

Gibson, C. C., Andersson, K., Ostrom, E., & Shivakumar, S. (2005). The Samaritan's

Dilemma: The Political Economy of Development Aid. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Other Pertinent Course Information

You are allowed to use electronic devices during class time for appropriate purposes (i.e. writing, working with students). Inappropriate use of electronic devices (i.e. for purposes not related to the class) is disrespectful and disruptive. If inappropriate use is frequent, this privilege will be suspended.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a federal anti-discrimination statute that provides comprehensive civil rights protection for persons with disabilities. Among other things, this legislation requires that all students with disabilities be guaranteed a learning environment that provides for reasonable accommodation of their disabilities. If you believe you have a disability requiring an accommodation, please contact Disability Services, in Cain Hall, Room B118, or call

845-1637. For additional information visit http://disability.tamu.edu

Academic Integrity

You are expected to follow the Aggie Honor code. For additional information please visit: http://aggiehonor.tamu.edu

“An Aggie does not lie, cheat, or steal, or tolerate those who do.”

Course Outline

Week 1 (August 31-September 6): Course Introduction: institutions and rules as a framework for understanding environmental governance

Steinberg, P. F. (2015). Who Rules the Earth? How Social Rules Shape Our Planet and

Our Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lemos, M. C., & Agrawal, A. (2006). Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ.

Resour., 31 , 297-325.

Thiel, A., Mukhtarov, F., & Zikos, D. (2015). Crafting or designing? Science and politics for purposeful institutional change in Social–Ecological Systems. Environmental Science

& Policy, 53, Part B , 81-86. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.018

Primack, R. B., Cigliano, J. A., & Parsons, E. C. M. (2014). Editorial: Coauthors gone bad; how to avoid publishing conflict and a proposed agreement for co-author teams.

Biological Conservation, 176(0), 277-280. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.06.003

Week 2 (Sept 7-13): Collective Action as a core problem

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective

Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Agrawal, A. (2001). Common Property Institutions and Sustainable Governance of

Resources. World Development, 29(10), 1649-1672.

Cox, M., Arnold, G., & Villamayor Tomás, S. (2010). A Review of Design Principles for

Community-based Natural Resource Management. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 38.

Week 3 (Sept 14-20): The Political-economic view of institutions.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance . New

York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Henrich, J. P., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., . . .

Ziker, J. (2006). Costly Punishment Across Human Societies. Science, 312(5781), 1767-

1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1127333

Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political Science and the Three New

Institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44 (5), 936-957.

Week 4 (Sept 21-27): Methods for Institutional Analysis

Poteete, A. R., Janssen, M., & Ostrom, E. (2010). Working together : collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press.

Bernard, H. R. (2011). Chapter 8 - Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing

Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Walnut

Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Cox, M. (2015). A basic guide for empirical environmental social science. Ecology and

Society, 20(1). doi: 10.5751/ES-07400-200163

Week 5 (Sept 28-Oct 4): Delving deeper into Institutional Analysis

Initial Project Proposal due this week.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

McGinnis, M. D. (2011). An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom

Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1),

169-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00401.x

Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Chapter 1: Rules games & Common pool resource problems in Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-

Pool Resources. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. P. 3-22

Week 6 (Oct. 5-11): Institutional Analysis of Governments and public programs

Gibson, C. C., Andersson, K., Ostrom, E., & Shivakumar, S. (2005). The Samaritan's

Dilemma: The Political Economy of Development Aid. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arnold, G., & Fleischman, F. D. (2013). The Influence of Organizations and Institutions on Wetland Policy Stability: The Rapanos Case. Policy Studies Journal, 41(2), 343-364. doi: 10.1111/psj.12020

Fleischman, F. D. (2014). Why do Foresters Plant Trees? Testing Theories of

Bureaucratic Decision-Making in Central India. World Development, 62 , 62-74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.008

Capano, G., Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2015). Bringing Governments Back in:

Governance and Governing in Comparative Policy Analysis. Journal of Comparative

Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 17 (4), 311-321. doi:10.1080/13876988.2015.1031977

Week 7 (Oct 12-18): Alternative theories of the policy process: Policy Process theory

Sabatier, P. A., & Weible, C. M. (2014). Theories of the Policy Process . New York:

Westview Press.

Meier, K. J. (2009). Policy Theory, Policy Theory Everywhere: Ravings of a Deranged

Policy Scholar. Policy Studies Journal, 37 (1), 5-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-

0072.2008.00291.x

Cairney, P. (2013). Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: How Do We Combine the

Insights of Multiple Theories in Public Policy Studies? Policy Studies Journal, 41(1), 1-

21. doi: 10.1111/psj.12000

Week 8 (Oct 19-25): Property and institutional analysis

Coase, R. H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3 , 1-

44.

Selections from Bromley, D. W. (1991). Environment and Economy: Property Rights and

Public Policy. Oxford: Blackwell.

McKean, M. A. (2000). Common Property: What is it, What is it good for, and What

Makes it Work. In C. C. Gibson, M. A. McKean, & E. Ostrom (Eds.), People and

Forests: Communities, Institutions, and Governance . Cambridge, MA: The MIT PRess.

Schlager, E., & Ostrom, E. (1992). Property-Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A

Conceptual Analysis. Land Economics, 68 (3), 249-262.

Galik, C. S., & Jagger, P. (2015). Bundles, Duties, and Rights: A Revised Framework for

Analysis of Natural Resource Property Rights Regimes. Land Economics, 91 (1), 76-90.

Ostrom, E. (2003). How Types of Goods and Property Rights Jointly Affect Collective

Action. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 15 (3), 239-270. doi:

10.1177/0951692803015003002

Week 9 (Oct 26-Nov 1): Large-scale social-ecological Systems

Preliminary Report of fieldwork due this week

Entire Special Issue of the International Journal of the Commons, Volume 8, number 2, on large-scale social-ecological systems “Introducing SESMAD” – pgs. 265-456 – please also study the SESMAD website, http://sesmad.dartmouth.edu.

Guest Lecture by Michael Cox

Week 10 (Nov 2-8): Power and Change

Selections from Knight, J. (1992). Institutions and Social Conflict. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Rochon, T. R., & Mazmanian, D. A. (1993). Social Movements and the Policy Process.

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 528, 75-87.

Agrawal, A. (2005). Environmentality: Community, Intimate Government, and the

Making of Environmental Subjects in Kumaon, India. Current anthropology, 46(2), 161-

190. doi: doi:10.1086/427122

Moe, T. (2005). Power and Political Institutions. Perspectives on Politics, 3, 215-233.

Cepek, M. L. (2011). Foucault in the forest: Questioning environmentality in Amazonia.

American Ethnologist, 38 (3), 501-515. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1425.2011.01319.x

Kashwan, P. (2015). Integrating power in institutional analysis: A micro-foundation perspective. Journal of Theoretical Politics . doi: 10.1177/0951629815586877

Week 11 (Nov 9-15): Institutional Analysis of Decentralization, Participation, & Communitybased conservation

Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of

Community in Natural Resource Conservation. World Development, 27(4), 629-649.

Agrawal, A., & Ribot, J. C. (1999). Accountability in Decentralization: A Framework with South Asian and West African Cases. The journal of developing areas, 33(4), 473-

502.

Agrawal, A., & Chhatre, A. (2006). Explaining success on the commons: Community forest governance in the Indian Himalaya. World Development, 34(1), 149-166.

Chhatre, A. (2008). Political Articulation and Accountability in Decentralisation: Theory and Evidence from India. Conservation and Society, 6(1), 12-23.

Fleischman, F.D. & Rodriguez Solorzano, C. (in prep). Supply and demand for

Participation.

Week 12 (Nov 16-22): TBA

Dr. Fleischman will be away on Tuesday Nov. 17. Possible guest lecture by Marty

Anderies on this date. Readings to be organized in conjunction with Anderies’ visit.

Depending on schedule, weekly memo may be due on Thursday.

Rough Draft of Project report due this week

Week 13: (Nov 23-29): Thanksgiving break: No class

Week 14: (Nov 30-Dec 6): Class time to complete the group project

Week 15: LAST DAY OF CLASS: DEC. 8 Final Project report due this class period.