Govt overview with SC Cases

advertisement

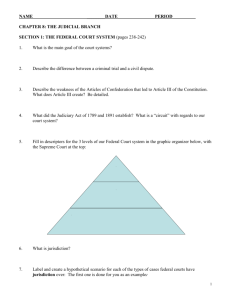

All right, you people, now you are in my area—the judicial system. And we’re going to learn about the American System of Justice That’s right, Judge Judy. Judge Wapner here. We’ll start by talking in general about American courts. First off, Judges do more than make decisions based on laws; they actually make laws. When judges announce specific decisions, they also provide the legal grounds for those decisions. Those grounds serve as precedents: guiding principles for determining what is legal in future situations that involve similar issues. Other judges—and lawyers—use these precedents in guiding their actions. so, judges by making precedents, actually make law, with no checks or balances. Article III of the Constitution: “the judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may . . . establish.” This provision gives the federal courts their jurisdiction—the authority to interpret and administer the law. The words of the Constitution are vague. Chief Justice John Marshall provided details regarding what the courts may do with his ruling in the crucial case of Marbury v. Madison (1803) John Adams commissioned William Marbury as DC Justice of the Peace. Midnight appointment New Secretary of State Madison refused to deliver; Marbury sued Marshall Court held: Madison had broken the law but that that part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional because it expanded the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court Marshall’s decision initiated the Court’s power of Judicial Review—interpreting what the law is Not used again until the decision in Dred Scott vs. Sanford in 1857 and only about 150 times since. Even though the Marshall Court’s decision in Marbury vs. Madison (1803) declared part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional, the structure of today’s federal court system was established by another part of that law. Lower federal courts have original jurisdiction: the authority to hear a case’s initial trial. But the limits on federal courts are that they may only hear cases arising under the Constitution and other federal laws, and other related factors—governments, foreign diplomats, etc. Lower courts are divided into district courts and courts of appeals District courts: trial courts in the federal court system They are assigned to specific geographic areas District courts make decisions in disputes based on the law and facts presented in the case Cases are tried before a district court judge and jury. Both sides present evidence, some of which is supplied by witnesses. Prosecutors represent the people; defense council represent defendants Courts of appeals hear appeals of cases that have been adjudicated by district courts There are 11 U. S. courts of appeals, each of which covers a jurisdiction called a circuit. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals covers the Western region: AK, HI, WA, OR, CA, NV, AZ, ID, and MT Each circuit court of appeals has 6-28 judges No juries; usually only 3 judges hear a case; however, at times the entire circuit court may hear a case—the Ninth Circuit and the Pledge of Allegiance “Under God” lawsuit Judges base their decisions on two inputs: written legal briefs submitted by the attorneys from both sides and from the written record from the actual trial Often, attorneys from both sides may also orally argue the case before a 3-judge panel The judges can reverse the lower court’s decision; affirm (or uphold) the lower court’s decision; or send the case back to the lower court for retrial. Usually, a reversal will come if the appeals court finds that the lower court did not properly apply a law. Students, also understand that federal judges serve “for life.” My fellow Founders and I wanted a system where judges could remain independent of political pressure. Federal judges are appointed by the President, and approved by the Senate. Through Senatorial Courtesy, presidents will give senators from their party who live in the region where the judge will serve the courtesy of reviewing and approving nominations. The United States Supreme Court Now, it’s our turn. Clarence Thomas (1991); Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1993); Stephen Breyer (1994); Samuel Alito (2006) Chief Justice: John Roberts (2005); John Paul Stevens (1975); Antonin Scalia (1986); Anthony Kennedy (1988), David Souter (1990) No background requirements: age, profession. But all have had significant preparation Constitution does not set size; Congress sets the size. The current number of 9 set 1869. Hello, again, students. Chief Justice John Marshall here. How long can a Supreme Court Justice serve, per the Constitution? “During good behavior” (or for life) Appointed by the President; approved by the U. S. Senate The Supreme Court is mostly an appeals court, reviewing cases from lower federal courts. About 12% of the cases we review come from state courts. Each year, the Supreme Court receives hundreds of cases. It sets its own agenda by choosing to hear cases on public policy issues that it considers the most pressing. Those cases are placed on the court’s docket (or schedule) Most people who petition the Supreme Court request a writ of certiorari. If the Court agrees to hear the case, it grants a cert under the Rule of Four—if 4 justices vote to hear the case. Lawyers who may argue before the Supreme Court must be members of the Supreme Court bar—having been a member of a state bar for at least 3 years and known to be of Good moral and professional character. For cases we choose to hear (about 140 out of the nearly 8,000 cases filed each year), lawyers for each side file written briefs—summaries of their arguments based on law, the Constitution, and evidence. If one of the sides in a case is the United States Government, the Solicitor General of the United States, an official of the Department of Justice, files the brief. Groups who are not the main parties but who have great interest in a case may file amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs as well After the Court has read the written briefs, lawyers for both sides present oral arguments before the Court. Generally, each side has 30-minutes to present its case; however, usually my colleagues and I use most of that time by asking them to respond to our (the justices’) questions. After hearing arguments on cases for about three weeks, the members of the Court go into consideration sessions—they discuss the cases, in order of seniority, starting with the Chief Justice, and decide how they will rule. If we are not unanimous, the senior person on each side of an issue assigns opinion-writing responsibilities. The majority opinion—the views of the majority of the court in both the outcome of the case and on the Court’s grounds for deciding it. Concurring opinions—a justice writes one of these if he/she agrees with the majority outcome, but disagrees with all or part of the grounds stated in the majority opinion. A justice might write a dissenting opinion if he or she disagrees with the decision reached by the majority. In this document, the justice notes the grounds for his or her dissent. The Supreme Court rarely reverses the decision of an earlier court, placing great weight on stare decisis—or upholding precedents set by earlier courts. There are major differences in civil and criminal cases. In a criminal law case, the people, or the prosecutor, must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, for example. But in a civil suit the plaintiff does not have to prove wrongdoing by the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt. That’s why I walked away acquitted of murder in 1996, but in the civil suit brought by Fred Goldman and others I lost almost everything. Since the decision of the Marshall Court in Marbury v. Madison (1803) Supreme Courts have made thousands of decisions. Some of them, however, have been so important, that they are considered landmark—or very important--decisions. In this short class we shall discuss some of those landmark decisions. Good evening Columbians. I was Chief Justice Earl Warren. Our first case was a multi-amendment case (with emphasis on the First Amendment) that my court, the Warren Court, decided: Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). A Connecticut law criminalized counseling married couples about or giving married couples medical treatment for the purposes of preventing conception of a child. Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) Issue: Does the Constitution protect the right of marital privacy against state restrictions on a couple’s ability to be counseled in the use of contraceptives? The Court held: together the First, Third, Fourth and Ninth Amendments create the right to privacy among married people. The Connecticut law was therefore unconstitutional and rendered null and void. Yet another case that the Warren Court, decided, similar in many respects to Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) was Loving v. Virginia (1967.) In 1958 a Virginia law was in effect that banned interracial marriages. Two residents of Virginia, Mildred Jeter, an African-American woman and Richard Loving, a white male, were married in Washington, D. C., and shortly after returned to Virginia. They were charged with violating the Virginia law, found guilty and sentenced each to a year in jail. Loving v. Virginia (1967) Issue: Did Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? In a unanimous decision, the Court held: that distinctions drawn according to race were generally “odious to a free people” and were subject to “the most rigid scrutiny” under the Equal Protection Clause. The Virginia law had no legitimate purpose “independent of invidious racial discrimination.” The Court further rejected Virginia’s argument that the statute was legitimate because it applied equally to blacks and whites. Columbians, I was Chief Justice Warren Burger. We will now discuss one of my Court’s landmark decisions in a case regarding the Fourteenth Amendment: Roe v. Wade (1973) Norma McCorvey (Roe), a Texas resident, sought to terminate her pregnancy by abortion, because the pregnancy was the result of rape. Texas law prohibited abortions except to save a pregnant woman’s life. Roe sued claiming that the Texas law violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Roe v. Wade (1973) Issue: Does the Constitution embrace a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy by abortion? The Burger Court held: a woman’s right to an abortion fell within the right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut--1965) protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision gave a woman total autonomy over her pregnancy during the first trimester. Now we are going to discuss 4 cases that primarily pertain to the rights of the accused in criminal cases. The first case is Mapp v. Ohio (1961) While searching her home for a fugitive, Ohio police discovered obscene materials in Dolree Mapp’s possession. The police admitted that the search of the home for the fugitive violated the Fourth Amendment. Still, Mapp was convicted of possessing obscene materials. Mapp v. Ohio (1961) Issues: 1) Were the confiscated materials protected by the First Amendment? 2) May evidence obtained in a search that violated the Fourth Amendment be used in a state court? The Court held: all evidence obtained through illegal searches and seizures is inadmissible in state court. This decision created the exclusionary rule, placing on all levels of government the requirement of excluding illegally obtained evidence from all criminal court proceedings. Our next case concerns the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments; specifically the right to counsel: Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) Gideon was arrested in Florida and charged with felony breaking and entering. He lacked funds to hire a lawyer and requested a courtappointed lawyer. The judge refused; Gideon defended himself, was convicted, and sentenced to 5 years in state prison. Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) Issue: Do the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments guarantee a right to legal counsel in all cases? The court held: Gideon had a right to be represented by a court-appointed attorney. Overruled Betts v. Brady (1942). Justice Black: “an obvious truth” that a fair trial for a poor defendant requires a competent legal counsel. “Lawyers are a necessity, not a luxury.” Another landmark decision dealing with the right of an accused person to an attorney was the 1964 decision, Escobedo v. Illinois. Escobedo was arrested in connection with a murder and, during interrogation at a local police station, the police denied him access to his attorney. Without his lawyer present, he confessed to firing the shot that killed the victim and, based on that confession, was convicted. Escobedo v. Illinois (1964) Issue: Is an accused person entitled to have an attorney present during questioning.? The Warren Court held: based on the “exclusionary rule” from Mapp v. Ohio (1961), the police obtained Escobedo’s confession in an illegal manner. His conviction was overturned. The Court also created the Escobedo Rule: based on the Sixth Amendment, police must warn an accused of the rights to remain silent and to have an attorney present during questioning. Columbians, Elle here. Our next case is one of the most famous in American history. It involves the Fifth Amendment: Miranda v. Arizona (1966) Miranda was arrested in Arizona and the police questioned him without advising him of his constitutional rights under the Fifth Amendment (selfincrimination.) He confessed to part of the crime. His confession was used in court and he was convicted, based, in part, on his confession. Miranda v. Arizona (1966) Issue: Did the police practice of interrogating individuals without advising them of their right to counsel and protection against self-incrimination violate the Fifth Amendment? The Court held: Prosecutors could not use statements in court that had been made by defendants unless police had advised them of their privilege against self-incrimination. The Court also specifically outlined what police warnings to suspects must include (right to remain silent, right to counsel present during questioning, etc.) In 1896 the Court ruled, in I was Justice Thurgood Marshall. When I was an attorney, I argued, and won, the single most important Supreme Court case regarding civil rights: Brown v. Board of Plessy v. Ferguson, Education of Topeka, KS that Blacks could be (1954). placed in separate facilities if they were “equal” to those used by whites. School districts therefore created separate “but equal” schools Brown v. Board of Education (1954) An African-American girl named Linda Brown lived near an all-white school in Topeka, KS. To get to her all-black school, she had to cross several dangerous roads and railroads. Her father, Oliver Brown, filed suit to overturn Plessy v. Ferguson to enable Linda Brown to attend the all-white school near her home. Issue: Did the “separate but equal” provision of Plessy v. Ferguson violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? Brown v. Board of Education (1954) The Warren Court held: Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal rule” was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Racial segregation in public education “has a detrimental effect on minority children because it is interpreted as a sign of inferiority.” Result: beginning of the end of all forms of state-maintained racial segregation.