Open House 2012

advertisement

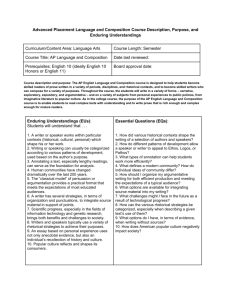

At the end of the course, each student will be able to read, interpret, speak, and write about a variety of fiction, nonfiction, dramatic, and poetic works, while utilizing an eloquent and scholastic vocabulary. As an introductory college-level course that is designed using the intentions of The College Board as stated and paraphrased here, students, as readers of prose that have been written in various rhetorical contexts, employ skilled reading techniques. In the same fashion, students develop writings to an array of purposes. Mutually working together, these reading and writing skills enable the student to be attentive to the large and subtle nuances in writer’s purpose, subject, and audience expectations. Furthermore, students analyze how genre conventions and the resources of language contribute to a writer’s power and influence. Students prepare for the AP English Language and Composition exam in May, which may grant advanced placement and/or college credit. Because of this, students spend a minimum of five hours of course work per week outside of class. This work involves both written and reading assignments. Gerard A. Hauser: Introduction to Rhetorical Theory (1986) “Rhetoric is an instrumental use of language. […] One person engages another person in an exchange of symbols to accomplish some goal. It is not communication for communication's sake. Rhetoric is communication that attempts to coordinate social action. For this reason, rhetorical communication is explicitly pragmatic. Its goal is to influence human choices on specific matters that require immediate attention. George Kennedy: "A Hoot in the Dark" (1992) “Rhetoric in the most general sense may perhaps be identified with the energy inherent in communication: the emotional energy that impels the speaker to speak, the physical energy expanded in the utterance, the energy level coded in the message, and the energy experienced by the recipient in decoding the message.” Bazerman, Charles: “The study of how people use language and other symbols to realize human goals and carry out human activities [. . .] ultimately a practical study offering people great control over their symbolic activity.” As a foundational course for all college disciplines, the AP English Language and Composition course includes a varied curriculum. The College Board notes that “the overarching objective in most firstyear writing courses is to enable students to write effectively and confidently in their college courses across the curriculum and in their professional and personal lives.” Class writings focus on the expository, analytical, and argumentative, which form the basis of most academic, professional, and personal pieces. Students read both primary and secondary works and synthesize these texts in their own compositions, while citing sources using the Modern Language Association (MLA) guidelines, the University of Chicago Press (The Chicago Manual Style) guidelines, and the American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. In the AP English Language and Composition course, students write for a mature reader by creating prose that surpass the canned five-paragraph essay, thereby, creating stronger connections with the reader. Writings emphasize content, purpose, and audience. These writings develop over several drafts and revisions and often include additional outside research. The researched argumentative pieces develop over time after reflection, interpretation, and analysis. Citations enhance the overall written text and move with the argument as integral components. In order to unite the reader with the piece, students develop style. Specifically, students use grammar, vocabulary, sentence structure, logical organization, and rhetoric for emphasis. From The College Board “Ordinarily, the exam consists of 60 minutes for multiple-choice questions, a 15-minute reading period to read the sources for the synthesis essay and plan a response, and 120 minutes for essay questions. Performance on the free-response section of the exam counts for 55 percent of the total score; performance on the multiple-choice section, 45 percent. Multiple-choice scores are based on the number of questions answered correctly. Points are not deducted for incorrect answers, and no points are awarded for unanswered questions.” Within the first quarter, students will be placed into a workshop group. This group will consist of three to four members and will meet during class time on prescribed days prior to the final deadline of all papers. On these days, students are required to bring in four copies of the paper such that each member has his/her own text to read. The writer will not bring in a rough draft but rather a finished product for the critique. Incomplete drafts can only earn 70% on these assignments. For instance, a one-two page draft is not considered complete, finished. On these workshop days, students will read, rethink, and help the writer clarify and enhance his/her paper. Preparation and participation on these days count for 10% of each quarter’s grade. As this is a crucial part of the writing process, absences on these days must be made up before the final turn in date. Make up workshop days will be held on a student scheduled afternoon at 3:00 in my classroom. The absent writer is responsible for organizing a reading group. Absences not made up will adversely affect his/her workshop grade. While reading class selections, students will maintain a journal. The structure of these entries may vary but should implement one of these strategies: dialectical journal, rhetorical journal, SOAPSTone, or OPTIC. Journals will be graded mostly on completion. The central components of this course are reading, analyzing, synthesizing, and writing. Grading policies match these aims. Traditional daily assignments are not given. In this way, this class follows those practices of a university by working and grading finished, summative tasks. Late work will not be accepted. Using AP rubrics, the final graded papers result from multiple drafts. At this stage, the papers will be evaluated for their final grades. Because this course is the equivalent of a college class, student grades are determined according to the following quarter breakdown, which varies from the English Department’s policies: Major Paper (First) Major Paper (Second) Timed Writings Multiple-Choice Workshop Preparation & Participation Journal 30% 35% 10% 10% 10% 5% *Quarter 1’s breakdown slightly differs from the above. The first summer reading essay is worth 5%. Major Paper #1 is 25%. Major Paper #2 is 35%. **Quarter 4—The first timed writing will count for the first Major Paper. Check Pinnacle Call me or email me: jsullivan@mayfieldschools.org; 440-9956970 Remind your child about my motto: “We are all striving for excellence.” I can and will meet with your child at any point during an assignment. The both of us will figure out how to meet the learning objectives and skills. I am available for extra help 3rd and 5th periods. None Encourage your child to read, even if he/she does not have assigned reading. Go to the library or bookstore and initiate at least an hour outside reading a day. Read the book with your child. Ask questions and have him/her come into class with questions. Ask to read over his/her paper. Point out any place where you are confused. Read the paper backwards, forwards. Does each sentence make sense? Last year 93.8% of our AP Language students earned college credit. Before leaving this evening and on the provided note card, please take a moment to tell me about your child. Have there been any hurdles in his/her learning? Is he/she quiet and reserved? Does he/she need that extra push? After all and as the parent, you know your child the best. Simply, is there anything that I need to know to promote his/her growth and potential?