Articles - Center Grove Community School Corporation

advertisement

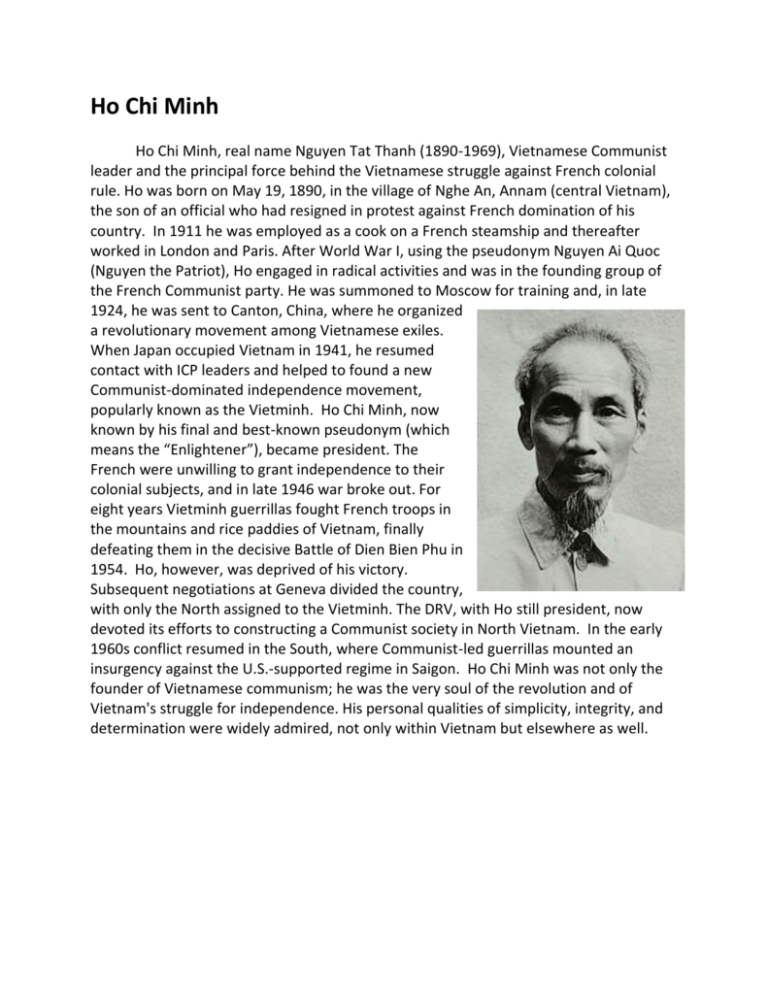

Ho Chi Minh Ho Chi Minh, real name Nguyen Tat Thanh (1890-1969), Vietnamese Communist leader and the principal force behind the Vietnamese struggle against French colonial rule. Ho was born on May 19, 1890, in the village of Nghe An, Annam (central Vietnam), the son of an official who had resigned in protest against French domination of his country. In 1911 he was employed as a cook on a French steamship and thereafter worked in London and Paris. After World War I, using the pseudonym Nguyen Ai Quoc (Nguyen the Patriot), Ho engaged in radical activities and was in the founding group of the French Communist party. He was summoned to Moscow for training and, in late 1924, he was sent to Canton, China, where he organized a revolutionary movement among Vietnamese exiles. When Japan occupied Vietnam in 1941, he resumed contact with ICP leaders and helped to found a new Communist-dominated independence movement, popularly known as the Vietminh. Ho Chi Minh, now known by his final and best-known pseudonym (which means the “Enlightener”), became president. The French were unwilling to grant independence to their colonial subjects, and in late 1946 war broke out. For eight years Vietminh guerrillas fought French troops in the mountains and rice paddies of Vietnam, finally defeating them in the decisive Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Ho, however, was deprived of his victory. Subsequent negotiations at Geneva divided the country, with only the North assigned to the Vietminh. The DRV, with Ho still president, now devoted its efforts to constructing a Communist society in North Vietnam. In the early 1960s conflict resumed in the South, where Communist-led guerrillas mounted an insurgency against the U.S.-supported regime in Saigon. Ho Chi Minh was not only the founder of Vietnamese communism; he was the very soul of the revolution and of Vietnam's struggle for independence. His personal qualities of simplicity, integrity, and determination were widely admired, not only within Vietnam but elsewhere as well. Dien Bien Phu The domino theory was the idea that if Vietnam fell to communism, its closest neighbors would follow. This in turn would threaten Japan, the Philippines, and Australia. In short, stopping the communists in Vietnam was important to the protection of the entire region. In 1954, the French lost their eight-year struggle to regain Vietnam. The Vietminh trapped a large French garrison at Dien Bien Phu, a military base in northwest Vietnam, and laid siege to it for 55 days. During the siege, which one Frenchman described as, “hell in a very small place,” Vietminh troops, led by Vo Nguyen Giap, destroyed the French airstrip, cut French supply lines, and dug trenches to attack key French positions. Finally, on May 7, 1954, after suffering 15,000 casualties, the French surrendered. The next day at an international peace conference in Geneva, Switzerland, France asked for peace in Vietnam. France granted independence to Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. According to the Geneva Accords, Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel into two countries, North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh’s communist forces ruled North Vietnam, and an anti-communist government, supported by the United States, assumed power in South Vietnam. Vietminh troops plant their flag over a captured French position. Ho Chi Minh (center) and Vo Nguyen Giap (right) plan the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Guerilla Warfare Ho Chi Minh and the Vietminh used a guerilla style of fighting against superior forces in Vietnam. He chose to use the style developed by Mao Zedong, communist leader of China. This Chinese rebel leader had fought a guerilla war for more than 20 years against his Nationalist opponents, eventually defeating them in 1949. This is the same style of fighting used by the American patriots against the British in the Revolutionary War. Mao instituted three distinctly different, but interrelated stages of guerilla warfare which were applied simultaneously: 1. Gain the support of the people – specifically the peasants in the countryside. This stage required guerillas to help poor farmers with their problems. The guerillas would do anything to gain the people’s support, respect, and trust, in order to eventually recruit them to fight in their organization. 2. Fight in small units using hit and run tactics – this strategy included blowing up barracks where the enemy eats and sleeps, killing unpopular leaders, and ambushing the enemy soldiers as they march to their next location. Guerillas were taught to immobilize their opponents by interrupted travel and drive them out of the countryside. 3. Obtain help from other communist countries – use captured weapons to create a credible, conventional military force. When the enemy is sufficiently weakened, mount full-scale attacks with conventional weapons. Ho Chi Minh modeled his strategy according to these stages of guerilla warfare. The basic strength of his movement lay in support from peasants who hated the French for what they had done to them. Many Vietnamese peasants lost their homes due to French rule and they did not want any further presence of foreign influence. North Vietnamese guerilla fighters, known as Vietcong, launched attacks in which they assassinated government officials and destroyed roads and bridges. Supplied by North Vietnam, the Vietcong used hit-and-run tactics to weaken the South Vietnamese and American soldiers. Vietcong guerillas relied on large tunnel networks to hide from—and launch surprise attacks against—American forces. Diagram of a Vietcong tunnel system. American soldiers search for Vietcong. Gulf of Tonkin Incident A few days after August 2, 1964, Americans heard that an American destroyer, the U.S.S. Maddox, had been attacked by North Vietnamese PT (patrol torpedo) boats. It seemed there had been no cause for this attack, which appeared to have taken place outside North Vietnamese territorial waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Maddox had escaped with one bullet hole, but was forced to dodge torpedoes from three North Vietnamese boats. The attack ended with one North Vietnamese patrol boat sunk and the other two badly damaged. President Lyndon Johnson warned North Vietnam that any further attacks would provoke “grave consequences.” Two days later, another “attack” occurred on the Maddox, and another destroyer, the Turner Joy. President Johnson responded by ordering full-scale air attacks against North Vietnam. He then went on national TV and proclaimed: “The North Vietnamese have decided to attack the U.S. This is plain for all the world to see. If we do not challenge these attacks they will continue…” President Johnson then issued the Gulf of Tonkin resolution to Congress to ask for full, wide-ranging military powers that would allow him to enter the U.S. into war in Vietnam. The resolution passed in Congress by a vote of 504-2. One of those opposed to the resolution was Senator Ernest Gruening. Senator Gruening objected, saying, "Sending our American boys into combat in a war in which we have no business, which is not our war, into which we have been misguidedly drawn, which is steadily being escalated". Years later, evidence came forward that proved the first attack on the Maddox may have been provoked by the American ship illegally entering enemy territory. Evidence also points towards the second “attack” having never even occurred at all. Either way, the U.S. was at war, and by the end of 1964, President Johnson had sent more than 23,000 troops to Vietnam.

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)