DOSCHER_Proposal_5_24_11_DEFENSE

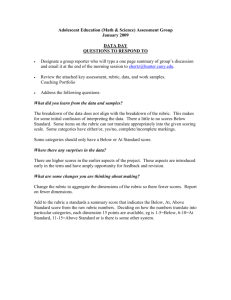

advertisement