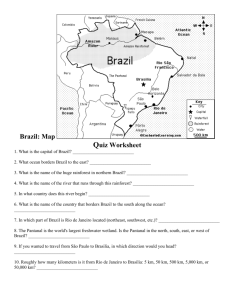

Full Text (Final Version , 485kb)

advertisement