Cinematography - DPSSFilmAppreciation

advertisement

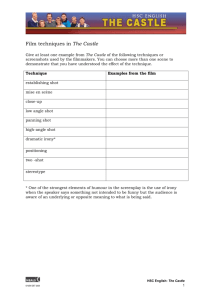

The use of the camera to create a world that we perceive on screen “Writing in pictures” Governed by certain conventions, but not restricted by these conventions; Reflecting and complementing the film’s other formal elements Setup: the camera’s position for a shot Shot: one uninterrupted run of the camera Take: the number of times a shot must be repeated (think “take two”) “There is no such thing as good photography per se. It is either right for a certain kind of film, and therefore good; or wrong- however lush, well-composed, meticulous- and therefore bad. “ “The cinematographer stands at the natural confluence of the main two streams of activity in the production of a film- where the imagination meets the reality of the film process.” “You will accomplish much more by fitting your cinematography to the story instead of limiting the story to the narrow confines of conventional photographic practice. And as you do so you’ll learn that the movie camera is a flexible instrument, with many of its possibilities left unexplored.” The cinematographer (Director of Photography) assisted by Camera operator and assistant camera operators (“ACs”) Electricians: “gaffer,” “best boy,” “grips” Gauges of film (8 mm – 70mm/IMAX) – width IMAX is 10 times bigger than a 35mm frame, and has been used recently for scenes in The Dark Knight and MI:Ghost Protocol Speed of film (fast, slow) – “graininess” Color Black-and-white In 1936, 1% of Hollywood films were shot in colour. By 1968 virtually all films were shot in colour. It is hard to imagine Sin City shot in full colour, or Metropolis, or The Night of the Hunter, or Persepolis. This year’s Best Picture Award winner at the Oscars was The Artist, shot in glorious Black and White! 1986, Film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert did a special episode of Siskel & Ebert addressing colorization as "Hollywood's New Vandalism." "It's about money" Siskel explained how networks were unable to show classic black-and-white films in prime-time unless they offer it in color. "They arrest people who spray subway cars, they lock up people who attack paintings and sculptures in museums, and adding color to black and white films, even if its only to the tape shown on TV or shown in stores, is vandalism nonetheless." Roger Ebert added, "What was so wrong about black and white movies in the first place? By filming in black and white, movies can sometimes be more dreamlike and elegant and stylized and mysterious. They can add a whole additional dimension to reality, while color sometimes just supplies additional unnecessary information." How shots are lit affects how we perceive them Lighting ratios: hard/high key, soft/low key 3-point system: keylight, fill light, backlight What’s NOT lit is an important aspect of lighting (just as offscreen space is as important as onscreen space) We will explore the 3 point system in a bit more detail a little later. It is the best known lighting convention in feature films. For now, consider this: The way a cinematographer lights and shoots an actor invariably affects how we look upon that character. The amount of light, the nature of the light, and the angle of the light are significant. This principle also works for settings and locations. The overall style of a film is determined by its production values, or the amount and quality of human and physical resources devoted to the image. A film’s lighting is an important element of its production values. Cinematographers work within the overall design of the film. In earlier years, each studio would cultivate its own distinct visual style as a form of “branding.” Cinematographers were compelled to work within those expectations. Additionally, cinematographers often work within the confines of a specific genre. Film Noir, for example, uses high contrast black and white tones to symbolize forces of good and evil. Westerns often employ bright exterior lighting and dim, underlit interiors, emphasizing the limitations of the indoor world and the expensiveness of the great outdoors. Focal length: wide, narrow angle, zoom. Different lenses are employed for different focal lengths (prime lenses, zoom lenses) Depth of field: what planes are in focus Aperture: an iris that limits light While a painter may select any shape of canvas he chooses, the cinematographer, throughout history, has been confined to variations on a rectangle, owing to the need for standardization of equipment and technology within the industry. Consider the theatres that show the films we watch. There are physical restraints on the size and shape of the screen that can be accommodated. In the 1930’s, as the industry boomed, a standard aspect ratio of 1:33:1 was adopted. Every theatre was equipped to this standard. (We might call it a 4:3 ratio today. In other words, the shape of the TV you owned before you owned your new one!) Television had a significant effect upon the film industry as it progressively drew viewers away from the movies. Something had to be done, so film companies turned to widescreen presentation in order to provide viewers an experience they could not have at home. (3D was an another early 50’s gimmick, as was smell-o-vision!) The Tingler was a 1959 horror-thriller about a scientist who discovers a parasite in humans called a tingler. The film tells the story of a scientist who discovers a parasite in human beings, called a "Tingler", which feeds on fear. The creature earned its name by making the spine of its host "tingle" when the host is frightened. The gimmick used for marketing The Tingler was called "Percepto!", which featured vibrating devices in some of the theater chairs which activated in time with the onscreen action! Starting in 1952, companies experimented with widescreen aspect ratios, some of the most common include: 1:66:1 European Widescreen 1:85:1 American Widescreen 2:2:1 Super Panavision and Todd A-O 2:35:1 Panavision and Cinemascope 2:75:1 Ultra Panavision Consider the implications of what these different ratios mean. Here is Picasso’s Guernica: (You saw this painting in Children of Men) How would you show this painting in Academy Standard? (Think of your old TV) You could crop it by cutting off the outside edges and always focusing on the centre of the screen. Tis would be disastrous when we consider The Rule of Threes You could Pan and Scan, constantly shifting the area of focus across the original “widescreen” painting You could show it in letterbox, leaving black bars across the top and bottom of your screen. You won’t lose any of the painting, but the image will be smaller and lack clarity You could squeeze the image, distorting it out of recognition Pan and Scan involved panning and scanning back and forth across the widescreen image so that the main action of the scene was always the focal point of what you saw. But what didn’t you see? You might see the speaker, but not the person being spoken to. You might see 2 of the 4 cowboys riding the range. In short, what you might see is this: We will watch some widescreen examples later this week. One of the best examples of widescreen can be seen in Ben Hur, the 1959 classic that won 11 Academy Awards. The highlight of that film is the famous chariot race, which still amazes today! It was filmed to be projected at a 2:75:1 aspect ratio! When we watch it, consider the challenge of showing this film on TV. Imagine a lowly technician at the Louvre museum trying to solve a problem. He’s got a bunch of oversized paintings, a bunch of undersized frames that the paintings don’t fit, and a boxcutter. By the time he’s done, the paintings now fit the frames. Absurd? Of course, but the widescreen frame image is beautifully composed and balanced, as we will see. It is unthinkable that someone other than the director should tamper with the image. Slow-motion emphasizes the action Fast-motion is usually funny Long take (film permits 10 minutes, but this can be extended) creates feeling of real time and space Contrast a Michael Bay or a Bourne film or Run Lola Run with Children of Men or something more measured, like Road to Perdition, or Citizen Kane, or Shawshank Redemption. Closeup shot Medium shot (typical) Long shot and gradations of these three i.e., XCS, XLS, MCS Deep-space composition Deep-focus cinematography The rule of thirds Eye-level shot (from typical POV) High angle shot (from overhead) Low angle (from below) Dutch angle (tilted) Aerial view (from above – long shot) Pan shot (“All the Things I Wasn’t”) Tilt shot Dolly or tracking shot (The Shining/The Godfather) Zoom shot (a camera effect) (See DVD Tutorial) Crane shot (Touch of Evil) Handheld or steadicam shot (Atonement/Goodfellas) Omniscient POV (most “usual”) Single-character POV (can also rotate) Group POV Slow Motion decelerates action to build suspense and prolong tension to convey subjectivity and memory to demonstrate heightened awareness Conveys an altered state of consciousness Often used for comedic effect To give a heightened sense of the passing of time Gives a sense of an unpredictable landscape/location (“The time is out of joint”) Average length of a shot is 10 seconds Long take can run from 1 to 10 minutes Allows film-makers to preserve real space and real time through an absence of cuts The long take can eliminate the need for multiple set ups. Consider the dolly shot in Shawshank Redemption when the camera closes in on Red at his parole hearing. permits the development of a story involving more than 2 lines of action without crosscutting allows cause and effect (the heart of narrative) to be recorded in one shot Steadicam allows for scenes to unfold in multiple locations with a fluid progression within the scene. Used to great effectiveness in Children of Men