First published in America in 2010 by

Eden Press

400 West 1st Street, Chico, California 95926

© 2010 by Eden Press

All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage

or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed and Bound in the United States of America

5

4

3

2

1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

For Your Eyes Only: An Anthology of Banned and Controversial Literature of the 20th Century and

Beyond / 1st Edition

Edited by: Cassi Deremo, Daniel Lopez, Cassandra Jones, Lauren Morrison, and Danielle Astengo

ISBN 978-1234567897

1

A word to the unwise.

Torch every book.

Char every page.

Burn every word to ash.

Ideas are incombustible.

And therein lies your real fear.

--John Lundberg

2

The Elephant Is Slow To Mate

D.H. Lawrence

The elephant, the huge old beast,

is slow to mate;

he finds a female, they show no haste

they wait

for the sympathy in their vast shy hearts

slowly, slowly to rouse

as they loiter along the river-beds

and drink and browse

and dash in panic through the brake

of forest with the herd,

and sleep in massive silence, and wake

together, without a word.

So slowly the great hot elephant hearts

grow full of desire,

and the great beasts mate in secret at last,

hiding their fire.

Oldest they are and the wisest of beasts

so they know at last

how to wait for the loneliest of feasts

for the full repast.

They do not snatch, they do not tear;

their massive blood

moves as the moon-tides, near, more near

till they touch in flood.

3

From “Shame,” The Rainbow

D.H. Lawrence

The bungalow was a tiny, two-roomed shanty set on a steep bank. Everything in it

was exquisite. In delicious privacy, the two girls made tea, and then they talked. Ursula

need not be home till about ten o’clock.

The talk was led, by a kind of spell, to love. Miss Inger was telling Ursula of a friend,

how she had died in childbirth, and what she suffered: then she told of a prostitute, and of

some of her experiences with men.

As they talked thus, on the little verandah of the bungalow, the night fell, there was a

little warm rain.

“It is really stifling,” said Miss Inger.

They watched a train, whose lights were pale in the lingering twilight, rushing across

the distance.

“It will thunder,” said Ursula.

The electric suspense continued, the darkness sank, they were eclipsed.

“I think I shall go and bathe,” said Miss Inger, out of the cloud-black darkness.

“At night?” said Ursula.

“It is best at night. Will you come?”

“I should like to”

“It is quite safe—the grounds are private. We had better undress in the bungalow,

for fear of the rain, then run down.”

Shyly, stiffly, Ursula went into the bungalow and began to remove her clothes. The

lamp was turned low, she stood in the shadow. By another chair Winifred Inger was

undressing.

Soon the naked, shadowy figure of the elder girl came to the younger.

“Are you ready?” she said.

“One moment.”

4

Ursula could hardly speak. The other naked woman stood by, stood near, silent.

Ursula was ready.

They ventured out into the darkness, feeling the soft air of night upon their skins.

“I can’t see the path,” said Ursula.

“It is here,” said the voice, and the wavering, pallid figure was beside her, a hand

grasping her arm. And the elder held the younger close against her, close, as they went

down, and by the side of the water, she put her arms round her, and kissed her. And she

lifted her in her arms, close, saying softly:

“I shall carry you into the water.”

Ursula lay still in her mistress’s arms, her forehead against the beloved, maddening

breast.

“I shall put you in,” said Winifred.

But Ursula twined her body about her mistress.

After a while the rain came down on their flushed, hot limbs, startling, delicious. A

sudden, ice-cold shower burst in a great weight upon them. They stood up to it with

pleasure. Ursula received the stream of it upon her breasts and her belly and her limbs. It

made her cold, and a deep, bottomless silence welled up in her, as if bottomless darkness

were returning upon her.

So the heat vanished away, she was chilled, as if from a waking up. She ran indoors, a

chill, non-existent thing, wanting to get away. She wanted the light, the presence of other

people, the external connection with the many. Above all she wanted to lose herself among

natural surroundings.

She took her leave of her mistress and returned home. She was glad to be on the

station with a crowd of Saturday-night people, glad to sit in the lighted, crowded railway

carriage. Only she did not want to meet anybody she knew. She did not want to talk. She

was alone, immune.

All this stir and seethe of lights and people was but the rim, the shores of a great

inner darkness and void. She wanted very much to be on the seething, partially illuminated

shore, for within her was the void reality of dark space.

5

For a time, Miss Inger, her mistress, was gone; she was only a dark void, and Ursula

was free as a shade walking in an underworld of extinction, of oblivion. Ursula was glad,

with a kind of motionless, lifeless gladness, that her mistress was extinct, gone out of her.

In the morning, however, the love was there again, burning, burning. She

remembered yesterday, and she wanted more, always more. She wanted to be with her

mistress. All separation from her mistress was a restriction from living. Why could she not

go to her today, today? Why must she pace about revoked at Cossethay, whilst her mistress

was elsewhere? She sat down and wrote a burning, passionate love-letter: she could not

help it.

6

Hiroshima Child

by Nazim Hikmet

I come and stand at every door

But none can hear my silent tread

I knock and yet remain unseen

For I am dead for I am dead

I'm only seven though I died

In Hiroshima long ago

I'm seven now as I was then

When children die they do not grow

My hair was scorched by swirling flame

My eyes grew dim my eyes grew blind

Death came and turned my bones to dust

And that was scattered by the wind

I need no fruit I need no rice

I need no sweets nor even bread

I ask for nothing for myself

For I am dead for I am dead

All that I need is that for peace

You fight today you fight today

So that the children of this world

Can live and grow and laugh and play

7

We Real Cool

Gwendolyn Brooks

THE POOL PLAYERS.

SEVEN AT THE GOLDEN SHOVEL.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

8

The Lottery

Shirley Jackson

The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day;

the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green. The people of the

village began to gather in the square, between the post office and the bank, around ten

o'clock; in some towns there were so many people that the lottery took two days and had to

be started on June 2th. but in this village, where there were only about three hundred

people, the whole lottery took less than two hours, so it could begin at ten o'clock in the

morning and still be through in time to allow the villagers to get home for noon dinner.

The children assembled first, of course. School was recently over for the summer, and the

feeling of liberty sat uneasily on most of them; they tended to gather together quietly for a

while before they broke into boisterous play. and their talk was still of the classroom and the

teacher, of books and reprimands. Bobby Martin had already stuffed his pockets full of

stones, and the other boys soon followed his example, selecting the smoothest and

roundest stones; Bobby and Harry Jones and Dickie Delacroix-- the villagers pronounced this

name "Dellacroy"--eventually made a great pile of stones in one corner of the square and

guarded it against the raids of the other boys. The girls stood aside, talking among

themselves, looking over their shoulders at rolled in the dust or clung to the hands of their

older brothers or sisters.

Soon the men began to gather. surveying their own children, speaking of planting and rain,

tractors and taxes. They stood together, away from the pile of stones in the corner, and

their jokes were quiet and they smiled rather than laughed. The women, wearing faded

house dresses and sweaters, came shortly after their menfolk. They greeted one another

and exchanged bits of gossip as they went to join their husbands. Soon the women,

standing by their husbands, began to call to their children, and the children came reluctantly,

having to be called four or five times. Bobby Martin ducked under his mother's grasping

hand and ran, laughing, back to the pile of stones. His father spoke up sharply, and Bobby

came quickly and took his place between his father and his oldest brother.

The lottery was conducted--as were the square dances, the teen club, the Halloween

program--by Mr. Summers. who had time and energy to devote to civic activities. He was a

round-faced, jovial man and he ran the coal business, and people were sorry for him.

because he had no children and his wife was a scold. When he arrived in the square, carrying

the black wooden box, there was a murmur of conversation among the villagers, and he

waved and called. "Little late today, folks." The postmaster, Mr. Graves, followed him,

9

carrying a three- legged stool, and the stool was put in the center of the square and Mr.

Summers set the black box down on it. The villagers kept their distance, leaving a space

between themselves and the stool. and when Mr. Summers said, "Some of you fellows want

to give me a hand?" there was a hesitation before two men. Mr. Martin and his oldest son,

Baxter. came forward to hold the box steady on the stool while Mr. Summers stirred up the

papers inside it.

The original paraphernalia for the lottery had been lost long ago, and the black box now

resting on the stool had been put into use even before Old Man Warner, the oldest man in

town, was born. Mr. Summers spoke frequently to the villagers about making a new box,

but no one liked to upset even as much tradition as was represented by the black box. There

was a story that the present box had been made with some pieces of the box that had

preceded it, the one that had been constructed when the first people settled down to make

a village here. Every year, after the lottery, Mr. Summers began talking again about a new

box, but every year the subject was allowed to fade off without anything's being done. The

black box grew shabbier each year: by now it was no longer completely black but splintered

badly along one side to show the original wood color, and in some places faded or stained.

Mr. Martin and his oldest son, Baxter, held the black box securely on the stool until Mr.

Summers had stirred the papers thoroughly with his hand. Because so much of the ritual had

been forgotten or discarded, Mr. Summers had been successful in having slips of paper

substituted for the chips of wood that had been used for generations. Chips of wood, Mr.

Summers had argued. had been all very well when the village was tiny, but now that the

population was more than three hundred and likely to keep on growing, it was necessary to

use something that would fit more easily into he black box. The night before the lottery, Mr.

Summers and Mr. Graves made up the slips of paper and put them in the box, and it was

then taken to the safe of Mr. Summers' coal company and locked up until Mr. Summers was

ready to take it to the square next morning. The rest of the year, the box was put way,

sometimes one place, sometimes another; it had spent one year in Mr. Graves's barn and

another year underfoot in the post office. and sometimes it was set on a shelf in the Martin

grocery and left there.

There was a great deal of fussing to be done before Mr. Summers declared the lottery open.

There were the lists to make up--of heads of families. heads of households in each family.

members of each household in each family. There was the proper swearing-in of Mr.

Summers by the postmaster, as the official of the lottery; at one time, some people

remembered, there had been a recital of some sort, performed by the official of the lottery,

a perfunctory. tuneless chant that had been rattled off duly each year; some people believed

that the official of the lottery used to stand just so when he said or sang it, others believed

10

that he was supposed to walk among the people, but years and years ago this p3rt of the

ritual had been allowed to lapse. There had been, also, a ritual salute, which the official of

the lottery had had to use in addressing each person who came up to draw from the box,

but this also had changed with time, until now it was felt necessary only for the official to

speak to each person approaching. Mr. Summers was very good at all this; in his clean white

shirt and blue jeans. with one hand resting carelessly on the black box. he seemed very

proper and important as he talked interminably to Mr. Graves and the Martins.

Just as Mr. Summers finally left off talking and turned to the assembled villagers, Mrs.

Hutchinson came hurriedly along the path to the square, her sweater thrown over her

shoulders, and slid into place in the back of the crowd. "Clean forgot what day it was," she

said to Mrs. Delacroix, who stood next to her, and they both laughed softly. "Thought my

old man was out back stacking wood," Mrs. Hutchinson went on. "and then I looked out the

window and the kids was gone, and then I remembered it was the twenty-seventh and came

a-running." She dried her hands on her apron, and Mrs. Delacroix said, "You're in time,

though. They're still talking away up there."

Mrs. Hutchinson craned her neck to see through the crowd and found her husband and

children standing near the front. She tapped Mrs. Delacroix on the arm as a farewell and

began to make her way through the crowd. The people separated good-humoredly to let

her through: two or three people said. in voices just loud enough to be heard across the

crowd, "Here comes your, Missus, Hutchinson," and "Bill, she made it after all." Mrs.

Hutchinson reached her husband, and Mr. Summers, who had been waiting, said cheerfully.

"Thought we were going to have to get on without you, Tessie." Mrs. Hutchinson said.

grinning, "Wouldn't have me leave m'dishes in the sink, now, would you. Joe?," and soft

laughter ran through the crowd as the people stirred back into position after Mrs.

Hutchinson's arrival.

"Well, now." Mr. Summers said soberly, "guess we better get started, get this over with,

so's we can go back to work. Anybody ain't here?"

"Dunbar." several people said. "Dunbar. Dunbar."

Mr. Summers consulted his list. "Clyde Dunbar." he said. "That's right. He's broke his leg,

hasn't he? Who's drawing for him?"

"Me. I guess," a woman said. and Mr. Summers turned to look at her. "Wife draws for her

husband." Mr. Summers said. "Don't you have a grown boy to do it for you, Janey?"

Although Mr. Summers and everyone else in the village knew the answer perfectly well, it

11

was the business of the official of the lottery to ask such questions formally. Mr. Summers

waited with an expression of polite interest while Mrs. Dunbar answered.

"Horace's not but sixteen vet." Mrs. Dunbar said regretfully. "Guess I gotta fill in for the old

man this year."

"Right." Sr. Summers said. He made a note on the list he was holding. Then he asked,

"Watson boy drawing this year?"

A tall boy in the crowd raised his hand. "Here," he said. "I m drawing for my mother and

me." He blinked his eyes nervously and ducked his head as several voices in the crowd said

thin#s like "Good fellow, lack." and "Glad to see your mother's got a man to do it."

"Well," Mr. Summers said, "guess that's everyone. Old Man Warner make it?"

"Here," a voice said. and Mr. Summers nodded.

A sudden hush fell on the crowd as Mr. Summers cleared his throat and looked at the list.

"All ready?" he called. "Now, I'll read the names--heads of families first--and the men come

up and take a paper out of the box. Keep the paper folded in your hand without looking at it

until everyone has had a turn. Everything clear?"

The people had done it so many times that they only half listened to the directions: most of

them were quiet. wetting their lips. not looking around. Then Mr. Summers raised one hand

high and said, "Adams." A man disengaged himself from the crowd and came forward. "Hi.

Steve." Mr. Summers said. and Mr. Adams said. "Hi. Joe." They grinned at one another

humorlessly and nervously. Then Mr. Adams reached into the black box and took out a

folded paper. He held it firmly by one corner as he turned and went hastily back to his place

in the crowd. where he stood a little apart from his family. not looking down at his hand.

"Allen." Mr. Summers said. "Anderson.... Bentham."

"Seems like there's no time at all between lotteries any more." Mrs. Delacroix said to Mrs.

Graves in the back row.

"Seems like we got through with the last one only last week."

"Time sure goes fast.-- Mrs. Graves said.

"Clark.... Delacroix"

12

"There goes my old man." Mrs. Delacroix said. She held her breath while her husband went

forward.

"Dunbar," Mr. Summers said, and Mrs. Dunbar went steadily to the box while one of the

women said. "Go on. Janey," and another said, "There she goes."

"We're next." Mrs. Graves said. She watched while Mr. Graves came around from the side of

the box, greeted Mr. Summers gravely and selected a slip of paper from the box. By now, all

through the crowd there were men holding the small folded papers in their large hand.

turning them over and over nervously Mrs. Dunbar and her two sons stood together, Mrs.

Dunbar holding the slip of paper.

"Harburt.... Hutchinson."

"Get up there, Bill," Mrs. Hutchinson said. and the people near her laughed.

"Jones."

"They do say," Mr. Adams said to Old Man Warner, who stood next to him, "that over in the

north village they're talking of giving up the lottery."

Old Man Warner snorted. "Pack of crazy fools," he said. "Listening to the young folks,

nothing's good enough for them. Next thing you know, they'll be wanting to go back to

living in caves, nobody work any more, live hat way for a while. Used to be a saying about

'Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.' First thing you know, we'd all be eating stewed

chickweed and acorns. There's always been a lottery," he added petulantly. "Bad enough to

see young Joe Summers up there joking with everybody."

"Some places have already quit lotteries." Mrs. Adams said.

"Nothing but trouble in that," Old Man Warner said stoutly. "Pack of young fools."

"Martin." And Bobby Martin watched his father go forward. "Overdyke.... Percy."

"I wish they'd hurry," Mrs. Dunbar said to her older son. "I wish they'd hurry."

"They're almost through," her son said.

"You get ready to run tell Dad," Mrs. Dunbar said.

13

Mr. Summers called his own name and then stepped forward precisely and selected a slip

from the box. Then he called, "Warner."

"Seventy-seventh year I been in the lottery," Old Man Warner said as he went through the

crowd. "Seventy-seventh time."

"Watson" The tall boy came awkwardly through the crowd. Someone said, "Don't be

nervous, Jack," and Mr. Summers said, "Take your time, son."

"Zanini."

After that, there was a long pause, a breathless pause, until Mr. Summers. holding his slip of

paper in the air, said, "All right, fellows." For a minute, no one moved, and then all the slips

of paper were opened. Suddenly, all the women began to speak at once, saving. "Who is

it?," "Who's got it?," "Is it the Dunbars?," "Is it the Watsons?" Then the voices began to say,

"It's Hutchinson. It's Bill," "Bill Hutchinson's got it."

"Go tell your father," Mrs. Dunbar said to her older son.

People began to look around to see the Hutchinsons. Bill Hutchinson was standing quiet,

staring down at the paper in his hand. Suddenly. Tessie Hutchinson shouted to Mr.

Summers. "You didn't give him time enough to take any paper he wanted. I saw you. It

wasn't fair!"

"Be a good sport, Tessie." Mrs. Delacroix called, and Mrs. Graves said, "All of us took the

same chance."

"Shut up, Tessie," Bill Hutchinson said.

"Well, everyone," Mr. Summers said, "that was done pretty fast, and now we've got to be

hurrying a little more to get done in time." He consulted his next list. "Bill," he said, "you

draw for the Hutchinson family. You got any other households in the Hutchinsons?"

"There's Don and Eva," Mrs. Hutchinson yelled. "Make them take their chance!"

"Daughters draw with their husbands' families, Tessie," Mr. Summers said gently. "You

know that as well as anyone else."

"It wasn't fair," Tessie said.

14

"I guess not, Joe." Bill Hutchinson said regretfully. "My daughter draws with her husband's

family; that's only fair. And I've got no other family except the kids."

"Then, as far as drawing for families is concerned, it's you," Mr. Summers said in

explanation, "and as far as drawing for households is concerned, that's you, too. Right?"

"Right," Bill Hutchinson said.

"How many kids, Bill?" Mr. Summers asked formally.

"Three," Bill Hutchinson said.

"There's Bill, Jr., and Nancy, and little Dave. And Tessie and me."

"All right, then," Mr. Summers said. "Harry, you got their tickets back?"

Mr. Graves nodded and held up the slips of paper. "Put them in the box, then," Mr. Summers

directed. "Take Bill's and put it in."

"I think we ought to start over," Mrs. Hutchinson said, as quietly as she could. "I tell you it

wasn't fair. You didn't give him time enough to choose. Everybody saw that."

Mr. Graves had selected the five slips and put them in the box. and he dropped all the

papers but those onto the ground. where the breeze caught them and lifted them off.

"Listen, everybody," Mrs. Hutchinson was saying to the people around her.

"Ready, Bill?" Mr. Summers asked. and Bill Hutchinson, with one quick glance around at his

wife and children. nodded.

"Remember," Mr. Summers said. "take the slips and keep them folded until each person has

taken one. Harry, you help little Dave." Mr. Graves took the hand of the little boy, who came

willingly with him up to the box. "Take a paper out of the box, Davy." Mr. Summers said.

Davy put his hand into the box and laughed. "Take just one paper." Mr. Summers said.

"Harry, you hold it for him." Mr. Graves took the child's hand and removed the folded paper

from the tight fist and held it while little Dave stood next to him and looked up at him

wonderingly.

"Nancy next," Mr. Summers said. Nancy was twelve, and her school friends breathed heavily

as she went forward switching her skirt, and took a slip daintily from the box "Bill, Jr.," Mr.

15

Summers said, and Billy, his face red and his feet overlarge, near knocked the box over as he

got a paper out. "Tessie," Mr. Summers said. She hesitated for a minute, looking around

defiantly. and then set her lips and went up to the box. She snatched a paper out and held it

behind her.

"Bill," Mr. Summers said, and Bill Hutchinson reached into the box and felt around, bringing

his hand out at last with the slip of paper in it.

The crowd was quiet. A girl whispered, "I hope it's not Nancy," and the sound of the whisper

reached the edges of the crowd.

"It's not the way it used to be." Old Man Warner said clearly. "People ain't the way they used

to be."

"All right," Mr. Summers said. "Open the papers. Harry, you open little Dave's."

Mr. Graves opened the slip of paper and there was a general sigh through the crowd as he

held it up and everyone could see that it was blank. Nancy and Bill. Jr.. opened theirs at the

same time. and both beamed and laughed. turning around to the crowd and holding their

slips of paper above their heads.

"Tessie," Mr. Summers said. There was a pause, and then Mr. Summers looked at Bill

Hutchinson, and Bill unfolded his paper and showed it. It was blank.

"It's Tessie," Mr. Summers said, and his voice was hushed. "Show us her paper. Bill."

Bill Hutchinson went over to his wife and forced the slip of paper out of her hand. It had a

black spot on it, the black spot Mr. Summers had made the night before with the heavy

pencil in the coal company office. Bill Hutchinson held it up, and there was a stir in the

crowd.

"All right, folks." Mr. Summers said. "Let's finish quickly."

Although the villagers had forgotten the ritual and lost the original black box, they still

remembered to use stones. The pile of stones the boys had made earlier was ready; there

were stones on the ground with the blowing scraps of paper that had come out of the box

Delacroix selected a stone so large she had to pick it up with both hands and turned to Mrs.

Dunbar. "Come on," she said. "Hurry up."

16

Mr. Dunbar had small stones in both hands, and she said. gasping for breath. "I can't run at

all. You'll have to go ahead and I'll catch up with you."

The children had stones already. And someone gave little Davy Hutchinson few pebbles.

Tessie Hutchinson was in the center of a cleared space by now, and she held her hands out

desperately as the villagers moved in on her. "It isn't fair," she said. A stone hit her on the

side of the head. Old Man Warner was saying, "Come on, come on, everyone." Steve Adams

was in the front of the crowd of villagers, with Mrs. Graves beside him.

"It isn't fair, it isn't right," Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.

17

The Beautiful Poem

Richard Brautigan

I got to bed in Los Angeles thinking

about you.

Pissing a few moments ago

I looked down at my penis

affectionately.

Knowing it has been inside

you twice today makes me

feel beautiful.

3 A.M.

January 15, 1967

18

The Color Purple

Alice Walker

You better not never tell nobody but God. It’d kill your mammy.

Dear God,

I am fourteen years old. I am I have always been a good girl. Maybe you can give me

a sign letting me know what is happening to me.

Last spring after little Lucious come I heard them fussing. He was pulling on her arm.

She say It too soon, Fonso, I ain’t well. Finally he leave her alone. A week go by, he pulling

on her arm again. She say Naw, I ain’t gonna. Can’t you see I’m already half dead, an all of

these children.

She went to visit her sister doctor over Macon. Left me to see after the others. He

never had a kine word to say to me. Just say You gonna do what your mammy wouldn’t.

First he put his thing up gainst my hip and sort of wiggle it around. Then he grab hold my

titties. Then he push his thing inside my pussy. When that hurt, I cry. He start to choke me,

saying You better shut up and git used to it.

But I don’t never git used to it. And now I feels sick every time I be the one to cook.

My mama she fuss at me an look at me. She happy, cause he good to her now. But too sick

to last long.

Dear God,

My mama dead. She die screaming and cussing. She scream at me. She cuss at me.

I’m big. I can’t move fast enough. By time I git back from the well, the water be warm. By

time I git the tray ready the food be cold. By time I git all the children ready for school it be

dinner time. He don’t say nothing. He set there by the bed holding her hand an crying,

talking bout don’t leave me, don’t go.

She ast me bout the first one Whose is it? I say God’s. I don’t know no other man or

what else to say. When I start to hurt and then my stomach start moving and then that little

baby come out my pussy chewing on it fist you could have knock me over with a feather.

Don’t nobody come see us.

She got sicker and sicker.

Finally she ast Where is it?

I say God took it.

He took it. He took it while I was sleeping. Kilt it out there in the woods. Kill this one

too, if he can.

19

Dear God,

He act like he can’t stand me no more. Say I’m evil an always up to no good. He took

my other little baby, a boy this time. But I don’t think he kilt it. I think he sold it to a man an

his wife over Monticello. I got breasts full of milk running down myself. He say Why don’t

you look decent? Put on something. But what I’m sposed to put on? I don’t have nothing.

I keep on hoping he fine somebody to marry. I see him looking at my little sister. She

scared. But I say I’ll take care of you. With God help.

Dear God,

He come home with a girl from round Gray. She be my age but they married. He be

on her all the time. She walk round like she don’t know what hit her. I think she thought she

love him. But he got so many of us. All needing somethin.

My little sister Nettie is got a boyfriend in the same shape almost as Pa. His wife died.

She was kilt by her boyfriend coming home from church. He got only three children though.

He seen Nettie in church and now every Sunday evening here come

Mr. _____. I tell Nettie to keep at her books. It be more then a notion taking care of

children ain’t even yourn. And look what happened to Ma.

Dear God,

He beat me today cause he say I winked at a boy in church. I may have got

something in my eye but I didn’t wink. I don’t even look at mens. That’s the truth. I look at

women, tho, cause I’m not scared of them. Maybe cause my mama cuss me you think I kept

mad at her. But I ain’t. I felt sorry for mama. Trying to believe his story kilt her.

Sometime he still be looking at Nettie, but I always git in his light. Now I tell her to

marry Mr. _____. I don’t tell her why.

I say marry him, Nettie, an try to have one good year out your life. After that, I know

she be big.

But me, never again. A girl at church say you git big if you bleed every month. I don’t

bleed no more.

Dear God,

Mr. _____ finally come right out an ast for Nettie hand in marriage. But He won’t let

her go. He say she too young, no experience. Say Mr. _____ got too many children already.

20

Plus What about the scandal his wife cause when somebody kill her? And what about all this

stuff he hear bout Shug Avery? What bout that?

I ast our new mammy bout Shug Avery. What it is? I ast. She don’t know but she say

she gon fine out.

She do more then that. She git a picture. The first one of a real person I ever seen.

She say Mr. _____ was taking somethin out his billfold to show Pa an it fell out an slid under

the table. Shug Avery was a woman. The most beautiful woman I ever saw. She more

pretty then my mama. She bout ten thousand time more prettier then me. I see her there in

furs. Her face rouge. Her hair like something tail. She grinning with her foot up on

somebody motocar. Her eyes serious tho. Sad some.

I ast her to give me the picture. An all night long I stare at it. An now when I dream, I

dream of Shug Avery. She be dress to kill, whirling and laughing.

Dear God,

I ast him to take me instead of Nettie while our new mammy sick. But he just ast me

what I’m talking bout. I tell him I can fix myself up for him. I duck into my room and come

out wearing horsehair, feathers, and a pair of our new mammy high heel shoes. He beat me

for dressing trampy but he do it to me anyway.

Mr. _____ come that evening. I’m in the bed crying. Nettie she finally see the light of

day, clear. Our new mammy she see it too. She in her room crying. Nettie tend to first one,

then the other. She so scared she go out doors and vomit. But not out front where the two

mens is.

Mr. _____ say, Well Sir, I sure hope you done change your mind.

He say, Naw, Can’t say I is.

Mr. _____say, Well, you know, my poor little ones sure could use a mother.

Well, He say, real slow, I can’t let you have Nettie. She too young. Don’t know

nothing but what you tell her. Sides, I want her to git some more schooling. Make a

schoolteacher out of her. But I can let you have Celie. She the oldest anyway. She ought to

marry first. She ain’t fresh tho, but I spect you know that. She spoiled. Twice. But you

don’t need a fresh woman no how. I got a fresh one in there myself and she sick all the time.

He spit, over the railing. The children git on her nerve, she not much of a cook. And she big

already.

Mr. _____he don’t say nothing. I stop crying I’m so surprise.

21

She ugly. He say. But ain’t no stranger to hard work. And she clean. And God done

fixed her. You can do everything just like you want to and she ain’t gonna make you feed it

or clothe it.

Mr. _____still don’t say nothing. I take out the picture of Shug Avery. I look into her

eyes. Her eyes say Yeah, it bees that way sometime.

Fact is, he say, I got to git rid of her. She too old to be living here at home. And she a

bad influence on my other girls. She’d come with her own linen. She can take that cow she

raise down there back of the crib. But Nettie you flat out can’t have. Not now. Not ever.

Mr. _____ finally speak. Clearing his throat. I ain’t never really look at that one, he

say.

Well, next time you come you can look at her. She ugly. Don’t even look like she kin

to Nettie. But she’ll make the better wife. She ain’t smart either, and I’ll just be fair, you

have to watch her or she’ll give away everything you own. But she can work like a man.

Mr. _____ say How old she is?

He say, She near twenty. And another thing—She tell lies.

Dear God,

It took him the whole spring, from March to June, to make up his mind to take me.

All I thought about was Nettie. How she could come to me if I marry him and he be so love

struck with her I could figure out a way for us to run away. Us both be hitting Nettie’s

schoolbooks pretty hard, cause us know we got to be smart to git away. I know I’m not as

pretty or as smart as Nettie, but she say I ain’t dumb.

The way you know who discover America, Nettie say, is think bout cucumbers. That

what Columbus sound like. I learned all about Columbus in first grade, but look like he the

first thing I forgot. She say Columbus come here in boats call the Neater, the Peter, and the

Santomareater. Indians so nice to him he force a bunch of ‘em back home with him to wait

on the queen.

But it hard to think with gitting married to Mr. _____ hanging over my head.

The first time I got big Pa took me out of school. He never care that I love it. Nettie

stood there at the gate holding tight to my hand. I was all dress for first day. You too dumb

to keep going to school, Pa say. Nettie the clever one in this bunch.

But Pa, Nettie say, crying, Celie smart too. Even Miss Beasley say so. Nettie dote on

Miss Beasley. Think nobody like her in the world.

Pa say, Whoever listen to anything Addie Beasley have to say. She run off at the

mouth so much no man would have her. That how come she have to teach school. He never

look up from cleaning his gun. Pretty soon a bunch of white mens come walking across the

yard. They have guns too.

Pa git up and follow ‘em. The rest of the week I vomit and dress wild game.

22

But Nettie never give up. Next thing I know Miss Beasley at our house trying to talk

to Pa. She say long as she been a teacher she never know nobody want to learn bad as

Nettie and me. But when Pa call me out and she see how tight my dress is, she stop talking

and go.

Nettie still don’t understand. I don’t neither. All us notice is I’m all the time sick and

fat.

I feel bad sometime Nettie done pass me in learnin. But look like nothing she say can

git in my brain and stay. She try to tell me something bout the ground not being flat. I just

say, Yeah, like I know it. I never tell her how flat it look to me.

Mr. _____ come finally one day looking all drug out. The woman he had helping him

done quit. His mammy done said No More.

He say, Let me see her again.

Pa call me. Celie, he say. Like it wasn’t nothing. Mr. _____ want another look at you.

I go stand in the door. The sun shine in my eyes. He’s still up on his horse. He look

me up and down.

Pa rattle his newspaper. Move up, he won’t bite, he say.

I go closer to the steps, but not too close cause I’m a little scared of his horse.

Turn round, Pa say.

I turn round. One of my little brothers come up. I think it was Lucious. He fat and

playful, all the time munching on something.

He say, What you doing that for?

Pa say, Your sister thinking bout marriage.

Didn’t mean nothing to him. He pull my dresstail and ast can he have some

blackberry jam out the safe.

I say, Yeah.

She good with children, Pa say, rattling his paper open more. Never heard her say a

hard word to nary one of them. Just give ‘em everything they ast for, is the only problem.

Mr. _____ say, That cow still coming.

He say, Her cow.

23

Education for Leisure

Carol Ann Duffy

Today I am going to kill something. Anything.

I have had enough of being ignored and today

I am going to play God. It is an ordinary day,

a sort of grey with boredom stirring in the streets.

I squash a fly against the window with my thumb.

We did that at school. Shakespeare. It was in

another language and now the fly is in another language.

I breathe out talent on the glass to write my name.

I am a genius. I could be anything at all, with half

the chance. But today I am going to change the world.

Something’s world. The cat avoids me. The cat

knows I am a genius, and has hidden itself.

I pour the goldfish down the bog. I pull the chain.

I see that it is good. The budgie is panicking.

Once a fortnight, I walk the two miles into town

for signing on. They don’t appreciate my autograph.

There is nothing left to kill. I dial the radio

and tell the man he’s talking to a superstar.

He cuts me off. I get our bread-knife and go out.

The pavements glitter suddenly. I touch your arm.

24

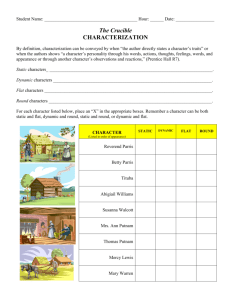

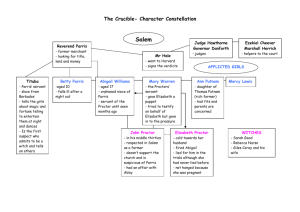

From The Crucible, Act 1

Arthur Miller

A small upper bedroom in the home of Reverend Samuel Parris, Salem, Massachusetts, in the

spring of they year 1692. There is a narrow window a the left. Through its leaded panes the

morning sunlight streams> A candle still burns near the bed, which is at the right. A chest, a

chair, and a small table are the other furnishings. At the back a cdoor opens on the landing of

the stairway to the ground floor. The room gives off an air of clean sparseness. The roof rafters

are exposed, and the wood colors are raw and unmellowed.

As the curtain rises, Reverend Parris is discovered kneeling beside the bed, evidently in prayer.

His daughter, Betty Parris, aged ten, is lying on the bed, inert. His niece, Abigail Williams,

seventeen, enters; she is all worry and propriety.

At the time of these events Parris was in his middle forties. In history he cut a

villainous path, and there is very little good to be said for him. He believed he was being

persecuted wherever he went, despite his best efforts to win people and God to his side. In

meeting, he felt insulted if someone rose to shut the door without first asking his

permission. He was a widower with no interest in children, or talent with them. He regarded

them as young adults, and until this strange crisis, he, like the rest of Salem, never conceived

that the children were anything but thankful for being permitted to walk straight, eyes

slightly lowered, arms at the sides, and mouths shut until bidden to speak.

His house stood in the “town” – but we today would hardly call it a village. The

meeting hose was nearby, and from this point outward – toward the bay or inland – there

were a few small-windowed, dark houses snuggling against the raw Massachusetts winter.

Salem had been established hardly forty years before; to the European world the whole

province was a barbaric frontier inhabited by a sect of fanatics who, nevertheless were

shipping out products of slowly increasing quantity and value.

No one can really know what their lives were like. They had no novelists – and would

not have permitted anyone to read a novel if one were handy. Their creed forbade anything

resembling a theater or “vain enjoyment.” They did not celebrate Christmas, and a holiday

from work meant only that they must concentrate even more on prayer.

Which is not to say that nothing broke into this strict and somber way of life. When a new

farmhouse was built, friends assembled to “raise the roof,” and there would be special

foods cooked and probably some potent cider passed around. There was a good supply of

ne’er-do-wells in Salem, who dallied at the shovelboard in Bridget Bishop’s tavern. Probably

25

more than the creed, hard work kept the morals of the place from spoiling for the people

were forced to fight the land like heroes for every grain of corn, and no man had very much

time for fooling around.

That there were some jokers, however, is indicated by the practice of appointing a

two-man patrol whose duty was to “walk forth in the time of God’s worship to take notice

of such as either lye about the meeting house, without attending to the word and

ordinances, or that lye at home or in the fields without giving good account thereof, and to

take the names of such persons and to present them to the magistrates, whereby they may

be accordingly proceeded against.” This predilection for minding other people’s business

was time-honored among the people of Salem, and it undoubtedly created many of the

suspicions which were to feed the coming madness. It was also, in my opinion, one of the

things that a John Proctor would rebel against, for the time of the armed camp had almost

passed, and since the country was reasonably – although not wholly – safe, the old

disciplines were beginning to rankle. But, as in all such matters the issue was not clear-cut,

for danger was still a possibility and in unity still laid the best promise of safety.

The edge of the wilderness was close by. The American continent stretched endlessly

west, and it was full of mystery for them. It stood dark and threatening, over r their

shoulders night and day, for out of it Indian tribes marauded from time to time and

Reverend Parris had parishioners who had lost relatives to these heathen.

Abigail: Uncle, the rumor of witchcraft is all about; I think you’d best go down and deny it

yourself. The parlor’s packed with people, sir. I’ll sit with her.

Parris: Abigail, I cannot go before the congregation when I know you have not opened with

me. What did you do with her in the forest?

Abigail: We did dance, uncle, and when you leaped out of the bush so suddenly, Betty was

frightened and then she fainted. And there’s the whole of it.

Parris: Now look you, child, your punishment will come in its time. But if you trafficked with

spirits in the forest, I must know it now, for surely my enemies will, and they will ruin me

with it.

Abigail: But we never conjured spirits.

Parris: Then why can she not move herself since midnight? This child is desperate! [Abigail

lowers her eyes]It must come out – my enemies will bring it out. Abigail, do you understand

that I have many enemies?

26

Abigail: I have heard of it, uncle.

Parris: There is a faction that is sworn to drive me from my pulpit? Do you understand that?

Abigail: I think so, sir.

Parris: Now, in the midst of such disruption, my own household is discovered to be the very

centre of some obscene practice. Abominations are done in the forest –

Abigail: It were sport, uncle!

Parris, pointing at Betty: You call this sport? Pause.

[Enter Mrs. Anne Putnam. She is a twisted soul of forty-five, a death-ridden woman, haunted by

dreams.]

Parris, as soon as the door begins to open: No—no, I cannot have anyone. He sees her. A

certain deference springs into him, although his worry remains.] Why Goody Putnam, come in.

Mrs. Putnam [full of breath, shiny eyed]: It is a marvel. It is surely a stroke of hell upon you.

Parris: No, Goody Putnam, it is –

Mrs. Putnam, glancing at Betty: How high did she fly, how high?

Parris: No, no, she never flew –

Mrs. Putnam: [very pleased with it] Why, it’s sure she did. Mr. Collins saw her goin’ over

Ingersoll’s barn, and come down light as bird, he says!

Parris: Now look your, Goody Putnam, she never – [Enter Thomas Putnam, a well-to-do, hardhanded landowner, near fifty.] Oh, good morning, Mr. Putnam.

Putnam: It is a providence the thing is out now! It is a providence. [He goes directly to the

bed.]

Parris: What’s out, sir, what’s – ?

[Mrs. Putnam goes to the bed]

Putnam: Why, her eyes is closed! Look you, Ann.

27

Mrs. Putnam: Why, that’s strange. To Parris: Ours is open.

Parris: Your Ruth is sick?

Mrs. Putnam: I’d not call it sick; the Devil’s touch is heavier than sick. It’s death, y’know, it’s

death drivin’ into them, forked and hoofed.

Parris: oh, pray not! Why, how does Ruth ail?

Mrs. Putnam: She ails as she must – she never waked this morning, but her eyes open and

she walks, and hears naught, sees naught, and cannot eat. Her soul is taken, surely.

[Parris is struck]

Putnam: [As though for further details] They say you’ve sent for Reverend Hale of Beverly?

Parris, with dwindling conviction now: A precaution only. He has much experience in all

demonic arts, and I—

Mrs. Putnam: He has indeed; and found a witch in Beverly last year, and let you remember

that.

Parris: Now, Goody Ann, they only thought that were a witch, and I am certain there be no

element of witchcraft here.

Putnam: No witchcraft! Now look you, Mr. Parris –

Parris: Thomas, Thomas, I pray you, leap not to witchcraft. I know that you – you least of all,

Thomas, would ever wish so disastrous a charge laid upon me. We cannot leap to witchcraft.

They will howl me out of Salem for such corruption in my house.

(3)

Mrs. Putnam: Reverend Parris, I have laid seven babies unbaptized in the earth.

They were murdered, Mr. Parris!

Putnam: Don’t you understand it, sir? There is a murdering witch among us, bound to keep

herself in the dark. Parris turns to Betty, a frantic terror rising in him. Let your enemies make

of it what they will, you cannot blink it more.

28

Parris, turns now, with new fear, and goes to Betty, looks down at her, and then, gazing off:

Oh, Abigail, what proper payment for my charity! Now I am undone.

Putnam: You are not undone! Let you take hold here. Wait for no one to charge you –

declare it yourself. You have discovered witchcraft!

Parris: Will you leave me now, I would pray a while alone.

Putnam: Come down, speak to them – pray with them. They’re thirsting for your word,

Mister! Surely you’ll pray with them.

Parris, swayed: I’ll lead them in a psalm, but let you say nothing of witchcraft yet.

Parris, Putnam, and Mrs. Putnam go out.

Mary Warren: Abby, we’ve got to tell! Witchery’s a hangin’ error, a hangin’ like they done in

Boson two years ago! We must tell the truth, Abby! You’ll only be whipped for dancin’, and

the other things!

Abigail: Oh, we’ll be whipped!

Mary Warren: I never done none of it, Abby. I only looked!

Betty, on bed, whimpers. Abigail turns to her at once.

Abigail: Betty? Goes to her. Now, Betty, dear, wake up now. It’s Abigail. She sits Betty up and

furiously shakes her. I’ll beat you, Betty! Betty whimpers. My, you seem improving. I talked to

your papa and I told him everything. So there’s nothing to –

Betty, darts off bed, frightened of Abigail, and flattens herself against the wall: I want my

mama!

Abigail, with alarm, as she cautiously approaches Betty: What ails you, Betty? Your mama’s

dead and buried.

Betty: I’ll fly to Mama. Let me fly! She raises her arms as though to fly, and streaks towards

window, gets one leg out.

29

Abigail, pulling her away from window: I told him everything; he knows now, he knows

everything we –

Betty: You drank blood, Abby! You didn’t tell him that! You drank a charm to kill John

Proctor’s wife! You drank a charm to kill Goody Proctor!

Abigail: Betty, you never say that again! You will never –

Betty: You did, you did! You drank a charm to kill John Proctor’s wife! You drank a charm to

kill Goody Proctor!

Abigail, smashes her across the face: Shut it! Now shut it! Betty collapses on bed, begins to sob.

Abigail: Now look you. All of you. We danced. And Tituba conjured Ruth Putnam’s dead

sisters. And that is all. And mark this. Let either of you breathe a word, or the edge of a

word, about the other things, and I will come to you in the black of some terrible night and I

will bring a pointy reckoning that will shudder you. And you know I can do it; I saw Indians

smash my dear parents’ heads on the pillow next to mine, and I have seen some reddish

work done at night, and I can make you wish you had never seen the sun go down! Goes and

roughly sits Betty up. Now, you – sit up and stop this!

Betty collapses in her ands and lies inert on the bed.

Mary Warren, with hysterical fright: What’s got her? Abigail stares in fright at Betty. Abby,

she’s going to die! It’s a sin to conjure, and we –

Abigail: I say shut it, Mary Warren!

30

From Scene 2, A Streetcar Named Desire

Tennessee Williams

Blanche: Never arithmetic, sir; never arithmetic! [With a laugh] I don't even know my

multiplication tables! No, I have the misfortune of being an English instructor. I attempt to

instill a bunch of bobby-soxers and drug-store Romeos with reverence for Hawthorne and

Whitman and Poe!

Mitch: I guess that some of them are more interested in other things.

Blanche: How very right you are! Their literary heritage is not what most of them treasure

above all else! But they're sweet things! And in the spring, it's touching to notice them

making their first discovery of love! As if nobody had ever known it before! [The bathroom

door opens and Stella comes out. Blanche continues talking to Mitch.] Oh ! Have you

finished? Wait - I'll turn on the radio.

[She turns the knobs on the radio and it begins to play ' Wien, Wien, nur du allein'. Blanche

waltzes to the music with romantic gestures. Mitch is delighted and moves in awkward

imitation like a dancing bear.

Stanley stalks fiercely through the portieres into the bedroom. He crosses to the small white

radio and snatches it off the table. With a shouted oath, he tosses the instrument out of the

window.]

Stella; Drunk - drunk - animal thing, you! [She rushes through to the poker table,'} All of you please go home I If any of you have one spark of decency in you –

Blanche [wildly]: Stella, watch out, he's [Stanley charges after Stella.]

Men [feebly]'. Take it easy, Stanley. Easy, fellow. - Let's all –

Stella: You lay your hands on me and I'll [She backs out of sight. He advances and disappears. There is the sound of a blow. Stella

cries out. Blanche screams and runs into the kitchen. The men rush forward and there is

grappling and cursing. Something is overturned with a crash.]

31

Blanche [shrilly]: My sister is going to have a baby 1

Mitch: This is terrible.

Blanche: Lunacy, absolute lunacy!

Mitch: Get him in here, men.

[Stanley is forced, pinioned by the two men, into the bedroom. He nearly throws them off.

Then all at once he subsides and is limp in their grasp. They speak quietly and lovingly to him

and he leans his face on one of their shoulders.]

Stella [in a high, unnatural voice, out of sight]: I want to go away, I want to go away !

Mitch: Poker shouldn't be played in a house with women.

[Blanche rushes into the bedroom.]

Blanche: I want my sister's clothes We’ll go to that woman's upstairs!

Mitch: Where is the clothes?

Blanche [opening the closet}: I've got them! [She rushes through to Stella.] Stella, Stella,

precious! Dear, dear little sister, don't be afraid!

[With her arms around Stella, Blanche guides her to the outside door and upstairs.]

Stanley [dully]: What's the matter; what's happened?

Mitch: You just blew your top, Stan.

Pablo: He's okay, now.

Steve: Sure, my boy's okay.

Mitch: Put him on the bed and get a wet towel.

Pablo: I think coffee would do him a world of good, now.

32

Stanley [thickly}: I want water.

Mitch: Put him under the shower.

[The men talk quietly as they lead him to the bathroom.]

Stanley: Let go of me, you sons of bitches I

[Sounds of blows are heard. The water goes on full tilt.]

Steve: Let's get quick out of here!

[They rush to the poker table and sweep u? their winnings on their way out.]

Mitch [sadly but firmly}: Poker should not be played in a house with women.

[The door closes on them and the place is still. The Negro entertainers in the bar around the

corner play 'Paper Doll' slow and blue. After a moment Stanley comes out of the bathroom

dripping water and still in his clinging wet polka dot drawers.]

Stanley: Stella! [There is a pause.] My baby doll's left me.

[He breaks into sobs. Then he goes to the phone and dials, still shuddering with sobs.]

Eunice ? I want my baby [He waits a moment; then he hangs up and dials again.} Eunice I'll

keep on ringin' until I talk with my baby

[An indistinguishable shrill voice is heard. He hurls phone to floor. Dissonant brass and piano

sounds as the rooms dim out to darkness and the outer walls appear in the night light. The

blue piano' plays for a brief interval. Finally, Stanley stumbles half-dressed out to the porch

and down the wooden steps to the pavement before the building. There he throws back his

head like a baying hound and bellows his wife's name: 'Stella! Stella, sweetheart! Stella!'

Stanley: Stell- lahhhhh

Eunice [calling down from the door of her upper apartment]; Quit that howling out there

an' go back to bed

33

Stanley: I want my baby down here. Stella, Stella

Eunice: She ain't comin' down so you quit I Or you'll git th' law on you I

Stanley: Stella!

Eunice: You can't beat a woman an' then call 'er back She won't come! And her goin' t' have

a baby ... You (You whelp of a Polack, you hope they do haul you in and turn the fire hose on

you, same as the last time

Stanley [humbly]: Eunice, I want my girl to come down with me!

Eunice: Hah I [She slams her door.]

Stanley [with heaven-splitting violence]. Stella- AHHHHH!

[The low-tone clarinet moans. The door upstairs opens again. Stella slips down the rickety

stairs in her robe. Her eyes are glistening with tears and her hair loose about her throat and

shoulders. They stare at each other. Then they come together with low, animal moans. He

falls on his knees on the steps and presses his face to her belly, curving a little with

maternity. Her eyes go blind with tenderness as she catches his head and raises him level

with her. He snatches the screen door open and lifts her off her feet and bears her into the

dark flat. Blanche comes out on the upper landing in her robe and slips fearfully down the

steps.]

Blanche: Where is my little sister? Stella? Stella?

[She- stops before the dark entrance of her sister's flat. Then catches her breath as if struck.

She rushes down to the walk before the house. She looks right and left as if for sanctuary,

The music fades away. Mitch appears from around tin comer.]

Mitch: Miss DuBois?

Blanche: oh

Mitch: All quiet on the Potomac now?

34

Blanche: She ran downstairs and went back in there with him.

Mitch: Sure she did.

Blanche: I'm terrified!

Mitch: Ho-ho I There's nothing to be scared of They're crazy about each other.

Blanche: I'm not used to such Mitch: Naw, it's a shame this had to happen when you just got here. But don't take it

serious.

Blanche: Violence! Is so Mitch: Set down on the steps and have a cigarette with me.

Blanche: I'm not properly dressed.

Mitch: That don't make no difference in the Quarter.

Blanche: Such a pretty silver case.

Mitch: I showed you the inscription, didn't I?

Blanche: Yes. [During the pause, she looks up at the sky.]

There's so much - so much confusion in the world.... [He coughs diffidently.] Thank you for

being so kind I need kindness now.

35

From “Nausicaa,” Ulysses

James Joyce

But Gerty was adamant. She had no intention of being at their beck and call. If they

could run like rossies she could sit so she said she could see from where she was. The eyes

that were fastened upon her set her pulses tingling. She looked at him a moment, meeting

his glance, and a light broke in upon her. Whitehot passion was in that face, passion silent as

the grave, and it had made her his. At last they were left alone without the others to pry and

pass remarks and she knew he could be trusted to the death, steadfast, a sterling man, a

man of inflexible honour to his fingertips. His hands and face were working and a tremour

went over her. She leaned back far to look up where the fireworks were and she caught her

knee in her hands so as not to fall back looking up and there was no-one to see only him and

her when she revealed all her graceful beautifully shaped legs like that, supply soft and

delicately rounded, and she seemed to hear the panting of his heart, his hoarse breathing,

because she knew too about the passion of men like that, hotblooded, because Bertha

Supple told her once in dead secret and made her swear she'd never about the gentleman

lodger that was staying with them out of the Congested Districts Board that had pictures cut

out of papers of those skirtdancers and highkickers and she said he used to do something

not very nice that you could imagine sometimes in the bed. But this was altogether different

from a thing like that because there was all the difference because she could almost feel him

draw her face to his and the first quick hot touch of his handsome lips. Besides there was

absolution so long as you didn't do the other thing before being married and there ought to

be women priests that would understand without your telling out and Cissy Caffrey too

sometimes had that dreamy kind of dreamy look in her eyes so that she too, my dear, and

Winny Rippingham so mad about actors' photographs and besides it was on account of that

other thing coming on the way it did.

And Jacky Caffrey shouted to look, there was another and she leaned back and the

garters were blue to match on account of the transparent and they all saw it and they all

shouted to look, look, there it was and she leaned back ever so far to see the fireworks and

something queer was flying through the air, a soft thing, to and fro, dark. And she saw a

long Roman candle going up over the trees, up, up, and, in the tense hush, they were all

breathless with excitement as it went higher and higher and she had to lean back more and

more to look up after it, high, high, almost out of sight, and her face was suffused with a

divine, an entrancing blush from straining back and he could see her other things too,

nainsook knickers, the fabric that caresses the skin, better than those other pettiwidth, the

green, four and eleven, on account of being white and she let him and she saw that he saw

36

and then it went so high it went out of sight a moment and she was trembling in every limb

from being bent so far back that he had a full view high up above her knee where no-one

ever not even on the swing or wading and she wasn't ashamed and he wasn't either to look

in that immodest way like that because he couldn't resist the sight of the wondrous

revealment half offered like those skirtdancers behaving so immodest before gentlemen

looking and he kept on looking, looking. She would fain have cried to him chokingly, held

out her snowy slender arms to him to come, to feel his lips laid on her white brow, the cry of

a young girl's love, a little strangled cry, wrung from her, that cry that has rung through the

ages. And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind blank and O! then the Roman candle

burst and it was like a sigh of O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures and it gushed out of it a

stream of rain gold hair threads and they shed and ah! they were all greeny dewy stars

falling with golden, O so lovely, O, soft, sweet, soft!

Then all melted away dewily in the grey air: all was silent. Ah! She glanced at him as

she bent forward quickly, a pathetic little glance of piteous protest, of shy reproach under

which he coloured like a girl He was leaning back against the rock behind. Leopold Bloom

(for it is he) stands silent, with bowed head before those young guileless eyes. What a brute

he had been! At it again? A fair unsullied soul had called to him and, wretch that he was, how

had he answered? An utter cad he had been! He of all men! But there was an infinite store of

mercy in those eyes, for him too a word of pardon even though he had erred and sinned and

wandered. Should a girl tell? No, a thousand times no. That was their secret, only theirs,

alone in the hiding twilight and there was none to know or tell save the little bat that flew so

softly through the evening to and fro and little bats don't tell.

Cissy Caffrey whistled, imitating the boys in the football field to show what a great

person she was: and then she cried:

— Gerty! Gerty! We're going. Come on. We can see from farther up.

Gerty had an idea, one of love's little ruses. She slipped a hand into her kerchief

pocket and took out the wadding and waved in reply of course without letting him and then

slipped it back. Wonder if he's too far to. She rose. Was it goodbye? No. She had to go but

they would meet again, there, and she would dream of that till then, tomorrow, of her

dream of yester eve. She drew herself up to her full height. Their souls met in a last lingering

glance and the eyes that reached her heart, full of a strange shining, hung enraptured on her

sweet flowerlike face. She half smiled at him wanly, a sweet forgiving smile, a smile that

verged on tears, and then they parted.

37

“Howl”

Allen Ginsberg

For Carl Solomon

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving

hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry

fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the

starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the

supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of

cities contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and saw Mohammedan angels

staggering on tenement roofs illuminated,

who passed through universities with radiant cool eyes hallucinating Arkansas and Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war,

who were expelled from the academies for crazy & publishing obscene odes

on the windows of the skull,

who cowered in unshaven rooms in underwear, burning their money in

wastebaskets and listening to the Terror through the wall,

who got busted in their pubic beards returning through Laredo with a belt

of marijuana for New York,

who ate fire in paint hotels or drank turpentine in Paradise Alley, death, or

purgatoried their torsos night after night

with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and

endless balls,

incomparable blind streets of shuddering cloud and lightning in the mind

leaping toward poles of Canada & Paterson, illuminating all the motionless world of Time between,

Peyote solidities of halls, backyard green tree cemetery dawns, wine drunkenness over the rooftops, storefront boroughs of teahead joyride neon

blinking traffic light, sun and moon and tree vibrations in the roaring

winter dusks of Brooklyn, ashcan rantings and kind king light of

mind,

who chained themselves to subways for the endless ride from Battery to holy

Bronx on benzedrine until the noise of wheels and children brought

them down shuddering mouth-wracked and battered bleak of brain

all drained of brilliance in the drear light of Zoo,

who sank all night in submarine light of Bickford's floated out and sat

38

through the stale beer afternoon in desolate Fugazzi's, listening to the

crack of doom on the hydrogen jukebox,

who talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue

to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge,

a lost battalion of platonic conversationalists jumping down the stoops off fire

escapes off windowsills of Empire State out of the moon,

yacketayakking screaming vomiting whispering facts and memories and

anecdotes and eyeball kicks and shocks of hospitals and jails and wars,

whole intellects disgorged in total recall for seven days and nights with

brilliant eyes, meat for the Synagogue cast on the pavement,

who vanished into nowhere Zen New Jersey leaving a trail of ambiguous

picture postcards of Atlantic City Hall,

suffering Eastern sweats and Tangerian bone-grindings and migraines of

China under junk-withdrawal in Newark's bleak furnished room,

who wandered around and around at midnight in the railroad yard wondering where to go, and went, leaving no broken hearts,

who lit cigarettes in boxcars boxcars boxcars racketing through snow toward

lonesome farms in grandfather night,

who studied Plotinus Poe St. John of the Cross telepathy and bop kabbalah

because the cosmos instinctively vibrated at their feet in Kansas,

who loned it through the streets of Idaho seeking visionary indian angels

who were visionary indian angels,

who thought they were only mad when Baltimore gleamed in supernatural

ecstasy,

who jumped in limousines with the Chinaman of Oklahoma on the impulse

of winter midnight streetlight smalltown rain,

who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or

soup, and followed the brilliant Spaniard to converse about America

and Eternity, a hopeless task, and so took ship to Africa,

who disappeared into the volcanoes of Mexico leaving behind nothing but

the shadow of dungarees and the lava and ash of poetry scattered in

fireplace Chicago,

who reappeared on the West Coast investigating the FBI in beards and shorts

with big pacifist eyes sexy in their dark skin passing out incomprehensible leaflets,

who burned cigarette holes in their arms protesting the narcotic tobacco haze

of Capitalism,

who distributed Supercommunist pamphlets in Union Square weeping and

undressing while the sirens of Los Alamos wailed them down, and

wailed down Wall, and the Staten Island ferry also wailed,

who broke down crying in white gymnasiums naked and trembling before

the machinery of other skeletons,

who bit detectives in the neck and shrieked with delight in policecars for

committing no crime but their own wild cooking pederasty and

39

intoxication,

who howled on their knees in the subway and were dragged off the roof

waving genitals and manuscripts,

who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and

screamed with joy,

who blew and were blown by those human seraphim, the sailors, caresses of

Atlantic and Caribbean love,

who balled in the morning in the evenings in rosegardens and the grass of

public parks and cemeteries scattering their semen freely to whomever come who may,

who hiccuped endlessly trying to giggle but wound up with a sob behind

a partition in a Turkish Bath when the blond & naked angel came to

pierce them with a sword,

who lost their loveboys to the three old shrews of fate the one eyed shrew

of the heterosexual dollar the one eyed shrew that winks out of the

womb and the one eyed shrew that does nothing but sit on her ass

and snip the intellectual golden threads of the craftsman's loom.

who copulated ecstatic and insatiate with a bottle of beer a sweetheart a

package of cigarettes a candle and fell off the bed, and continued

along the floor and down the hall and ended fainting on the wall with

a vision of ultimate cunt and come eluding the last gyzym of consciousness,

who sweetened the snatches of a million girls trembling in the sunset, and

were red eyed in the morning but prepared to sweeten the snatch of

the sunrise, flashing buttocks under barns and naked in the lake,

who went out whoring through Colorado in myriad stolen night-cars, N.C.,

secret hero of these poems, cocksman and Adonis of Denver--joy to

the memory of his innumerable lays of girls in empty lots & diner

backyards, moviehouses' rickety rows, on mountaintops in caves or

with gaunt waitresses in familiar roadside lonely petticoat upliftings

& especially secret gas-station solipsisms of johns, & hometown alleys

too,

who faded out in vast sordid movies, were shifted in dreams, woke on a

sudden Manhattan, and picked themselves up out of basements hungover with heartless Tokay and horrors of Third Avenue iron dreams

& stumbled to unemployment offices,

who walked all night with their shoes full of blood on the snowbank docks

waiting for a door in the East River to open to a room full of steamheat and opium,

who created great suicidal dramas on the apartment cliff-banks of the Hudson under the wartime blue floodlight of the moon & their heads shall

be crowned with laurel in oblivion,

who ate the lamb stew of the imagination or digested the crab at the muddy

bottom of the rivers of Bowery,

40

who wept at the romance of the streets with their pushcarts full of onions

and bad music,

who sat in boxes breathing in the darkness under the bridge, and rose up to

build harpsichords in their lofts,

who coughed on the sixth floor of Harlem crowned with flame under the

tubercular sky surrounded by orange crates of theology,

who scribbled all night rocking and rolling over lofty incantations which in

the yellow morning were stanzas of gibberish,

who cooked rotten animals lung heart feet tail borsht & tortillas dreaming

of the pure vegetable kingdom,

who plunged themselves under meat trucks looking for an egg,

who threw their watches off the roof to cast their ballot for Eternity outside

of Time, & alarm clocks fell on their heads every day for the next

decade,

who cut their wrists three times successively unsuccessfully, gave up and

were forced to open antique stores where they thought they were

growing old and cried,

who were burned alive in their innocent flannel suits on Madison Avenue

amid blasts of leaden verse & the tanked-up clatter of the iron regiments of fashion & the nitroglycerine shrieks of the fairies of advertising & the mustard gas of sinister intelligent editors, or were run down

by the drunken taxicabs of Absolute Reality,

who jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge this actually happened and walked

away unknown and forgotten into the ghostly daze of Chinatown

soup alleyways & firetrucks, not even one free beer,

who sang out of their windows in despair, fell out of the subway window,

jumped in the filthy Passaic, leaped on negroes, cried all over the

street, danced on broken wineglasses barefoot smashed phonograph

records of nostalgic European 1930s German jazz finished the whiskey and threw up groaning into the bloody toilet, moans in their ears

and the blast of colossal steamwhistles,

who barreled down the highways of the past journeying to the each other's

hotrod-Golgotha jail-solitude watch or Birmingham jazz incarnation,

who drove crosscountry seventytwo hours to find out if I had a vision or you

had a vision or he had a vision to find out Eternity,

who journeyed to Denver, who died in Denver, who came back to Denver

& waited in vain, who watched over Denver & brooded & loned in

Denver and finally went away to find out the Time, & now Denver

is lonesome for her heroes,

who fell on their knees in hopeless cathedrals praying for each other's salvation and light and breasts, until the soul illuminated its hair for a

second,

who crashed through their minds in jail waiting for impossible criminals

41

with golden heads and the charm of reality in their hearts who sang

sweet blues to Alcatraz,

who retired to Mexico to cultivate a habit, or Rocky Mount to tender Buddha

or Tangiers to boys or Southern Pacific to the black locomotive or

Harvard to Narcissus to Woodlawn to the daisychain or grave,

who demanded sanity trials accusing the radio of hypnotism & were left with

their insanity & their hands & a hung jury,

who threw potato salad at CCNY lecturers on Dadaism and subsequently

presented themselves on the granite steps of the madhouse with

shaven heads and harlequin speech of suicide, demanding instantaneous lobotomy,

and who were given instead the concrete void of insulin Metrazol electricity

hydrotherapy psychotherapy occupational therapy pingpong & amnesia,

who in humorless protest overturned only one symbolic pingpong table,

resting briefly in catatonia,

returning years later truly bald except for a wig of blood, and tears and

fingers, to the visible madman doom of the wards of the madtowns

of the East,

Pilgrim State's Rockland's and Greystone's foetid halls, bickering with the

echoes of the soul, rocking and rolling in the midnight solitude-bench

dolmen-realms of love, dream of life a nightmare, bodies turned to

stone as heavy as the moon,

with mother finally ******, and the last fantastic book flung out of the

tenement window, and the last door closed at 4 a.m. and the last

telephone slammed at the wall in reply and the last furnished room

emptied down to the last piece of mental furniture, a yellow paper

rose twisted on a wire hanger in the closet, and even that imaginary,

nothing but a hopeful little bit of hallucination-ah, Carl, while you are not safe I am not safe, and now you're really in the

total animal soup of time-and who therefore ran through the icy streets obsessed with a sudden flash

of the alchemy of the use of the ellipse the catalog the meter & the

vibrating plane,

who dreamt and made incarnate gaps in Time & Space through images

juxtaposed, and trapped the archangel of the soul between 2 visual

images and joined the elemental verbs and set the noun and dash of

consciousness together jumping with sensation of Pater Omnipotens

Aeterna Deus

to recreate the syntax and measure of poor human prose and stand before

you speechless and intelligent and shaking with shame, rejected yet

confessing out the soul to conform to the rhythm of thought in his

naked and endless head,