Unit 5 - Guthrie Public Schools

advertisement

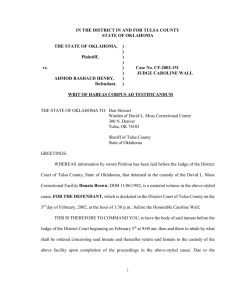

Unit 5 War and Development Governor Charles N. Haskell The states first governor March 1907 Haskell became publisher of the New State Tribune Haskell’s first official act as governor of the State of Oklahoma was to prevent Standard Oil Company from connecting a pipeline from Bartlesville into Kansas. Haskell’s action gave the state government time to decide upon necessary regulations for governing the pipeline industry before pipelines entered the state. The Oklahoma State Penitentiary was built at McAlester during Haskell’s administration. Moving the State Capital Haskell’s administration is best known for the removal of the state capital from Guthrie to Oklahoma City. The location of the Capital had been a matter of dispute since territorial days. The controversy began with the Organic Act in 1890 when Territorial Government was approved. Guthrie was named by that act as the meeting place of the first legislature. However the act also stated that the lawmaking body and the governor should name a permanent location as soon as they found it necessary. Some contending cities were granted other prizes to satisfy their hopes for importance in the Territory and later the state. Stillwater received OSU, Edmond UCO, Norman OU Moving Capital cont. IN 1906 Bird McGuire of Pawnee was a delegate to Congress. He saw a provision attached to the Enabling Act naming Guthrie as temporary state capital until 1913. An election was set for June 14, 1910 to name the capital site. Oklahoma City, Guthrie, and Shawnee were the Choices offered to the citizens. Before the Governor signed the proclamation announcing the election he changed the date from Tuesday June 14 to Saturday June 11. This meant that the results would become known on a Sunday when business offices were closed. Of the 135,000 votes counted almost 100,000 were for OKC. The governor arranged for a special train to OKC and contacted his Secretary W.B. Anthony to meet him there with Secretary of State Bill Cross and the State Seal Moving the Capital cont. With the help of the governor’s chief clerk, Paul Nesbitt, and two other employees of the governor’s office Earl Keys and Porter Spaulding, the state seal and the state recording book were removed from the vault and spirited out of the building through a watchful crowd of self-appointed guards. The articles were concealed in a bundle of laundry which Anthony claimed to have left in the Governors office earlier. Several legends survive concerning the transporting of the seal to OKC. Some say it was sent in a limo that was waiting outside the Guthrie office building. Others say an African-American man riding a mule carried it into the city. And others claim it went by train. However it was done it was done successfully. No real records were kept on the subject Moving cont. Lawsuits were filed and on November 15 the State Supreme Court ruled that the petition for election had contained a fatal error. It had not begun with the question, “Shall it be adopted.” The election therefore was void. The governor called a special session, he appealed too the governing body in the name of the people, pointing out that they had made their wishes known through a public election. The legislature ratified OKC as the new capital on December 16, 1910. Oil fields and Boom Towns The oil industry moved into the state at the turn of the century, and in 1905 the famous Glenn Pool was discovered on the Ida Glenn farm, ten miles south of Tulsa. The greatest problem of the big producers was transportation. While oil from other areas was bringing more than $2 a barrel prices at Glenn Pool from 25 cents to 40 cents per barrel because of the problem of getting the oil out of the field. By statehood the first pipelines had opened and in October 1907 the first Glenn Pool oil reached the refineries in Port Arthur Texas. The Glenn Pool brought several large companies into Oklahoma, such as the Texas Company (Texaco) , Gulf Oil Company, and Standard Oil of New Jersey. Boom towns cont. Boom towns sprang up in every oil field, creating law enforcement problems. Where a small village, or no town at all, had existed before, suddenly thousands of people came. Many were speculators and investors, and some were small business people who followed the oil booms, supplying customers with products and services. When a field was drilled out, the drillers began to leave and so did everyone else. The boom towns soon became ghost towns or returned to the size of small villages. Kiefer and Cushing were two such boom towns. The Oklahoma oil fields were still booming when the United States declared war on Germany in 1917. During World War I, oil was one of the state’s major contributions to the war effort. The Capital Building Construction of the new capitol building had begun during Governor Lee Cruce’s administration in June, 1914, and was completed in time for the legislature to meet in its new chambers during the 1917 session. The original plans for the capitol building had included a dome, for which there was not enough money appropriated, and the legislature agreed to postpone adding it. During the Frank Keating administration, construction on a dome was begun, and the new dome was dedicated on November 16, 2002. Oklahoman’s in WWI The first military units called from Oklahoma to serve a national cause were Oklahoma Territory’s Troop D and Troops L and M from Indian Territory. These men served in the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry commanded by Colonel Leonard Wood and Lt. Colonel Theodore Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War of 1898. After statehood, the Territorial Guard became the Oklahoma National Guard, and guardsmen were called to active duty in 1916 to serve under General John J. Pershing to protect the U.S.Mexican border. Those who served in Mexico returned home just in time for World War I. Oklahoma’s guardsmen shipped out with the 36th Infantry, the 42nd Infantry (known as the Rainbow Division), and the 90th Infantry Division (also called the Texas-Oklahoma Division). WWI cont. The first Oklahomans to arrive in France were those in the 36th Infantry Division. When the war ended on November 11, 1918 — at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month — 90,527 Oklahomans, including 5,000 African-Americans, had served their country’s cause. Of these, 4,154 were wounded in battle, 502 were missing in action, 1,064 were killed, and 502 died of disease. While the men were away fighting the war, the women were at home running things. They worked in munitions factories, in stores, on streetcars and on railroads. Women’s suffrage, or voting rights, became an issue. In 1918, at the close of the war, Oklahoma voters passed a state constitutional amendment giving Oklahoma’s women the right to vote, two years before the national amendment was adopted. Alice Mary Robertson In 1920 Alice Mary Robertson became the second woman ever to be elected to the United States Congress. During her short legislative career, Alice Mary Robertson became the first woman to preside over a session of the House of Representatives. Tulsa Race Riot The postwar period also brought a great deal of racial tension to the nation. This racial tension helped set the scene for the Tulsa race riot of 1921, billed by the New York Times as “the worst race riot in history.” The situation began when Dick Rowland, a nineteen-year-old bootblack in Tulsa, delivered a package to the Drexel Building downtown. He rode the elevator with Mrs. Sarah Page, a young white woman who was working as the elevator operator. Upon leaving the elevator, Rowland stumbled and stepped on Mrs. Page’s foot. Mrs. Page became frightened and screamed. Rowland, also frightened, ran from the building. Mrs. Page claimed Rowland had tried to assault her, and the young AfricanAmerican man was arrested the following day. Race Riot cont. Following Rowland’s arrest, the Tulsa Tribune printed the story of the incident, including false statements concerning torn clothing and scratches on Mrs. Page’s face. Despite the denials by Tulsa’s chief of police, county sheriff, and mayor that any harm had been done to the woman, and despite the admission of the managing editor of the Tulsa Tribune that the statements about Mrs. Page’s facial scratches and torn clothes were false, anger had been aroused among the city’s whites. Lynch talk began to circulate. By 7:00 p.m. on May 31, 1921, a crowd of white men were gathering around the County Courthouse. The jail in which Rowland was being held was on the third floor. Race Riot cont. By 9:30 p.m., a crowd of African-American men began to gather, also, determined not to allow Rowland to be lynched. Approximately 2,000 white men had gathered, and groups of African-American men were circling the block in cars. Several of both groups were reportedly armed. Pleas from law enforcement officials for the crowd to disperse were ignored. Some seventy-five African-American men exited the cars and began milling with the white crowd. This incensed several of the white men, and one white man tried to disarm an African-American man. During the ensuing struggle, the weapon discharged and the chaos began. Several shots were fired, and one white man sitting in his car a block away was killed by a stray bullet. When one African-American man was wounded and ambulances arrived to attend him, white rioters surrounded him and refused to let the ambulance attendants remove him. He died where he lay. Race Riot cont. By midnight, factions had formed combat lines along both sides of the railroad tracks which separated the African-American section from the white section of town. The worst fighting occurred between midnight and dawn of Wednesday, June 1. White mobs infiltrated the African-American areas, looting and burning the entire district and preventing firefighters from combating the fires. When the riot was over, between thirty and forty blocks of homes and businesses had been burned in the African-American sector of Tulsa. Race Riot cont. In Tulsa during the riot, white soldiers, law officers, and deputized volunteers disarmed African-Americans and took them prisoner. African-American prisoners were taken to Convention Hall, where they were searched and then transported to various holding camps around the city. White rioters, on the other hand, were simply disarmed and sent home. The total official death count was thirty- six — twenty-six African-Americans and ten whites The Ku Klux Klan On Thanksgiving night, 1915, outside Atlanta, Georgia, Colonel William Joseph Simmons and a handful of supporters resurrected the terror of the South, the Ku Klux Klan. By the 1920s, the Klan had reached a peak of power never before achieved, and Oklahoma was a prime Klan state. It was a ripe time for the basic Klan doctrines of patriotism, Protestantism, white supremacy, and law and order. Other segments of society were ignoring law and order by drinking bootleg liquor and participating in gambling and other unlawful forms of entertainment. A whole new vocabulary had to be learned in order to participate in the activities. A bootlegger was a man who stuffed his cowboy boots with small, flat bottles of illegal liquor. A moonshiner distilled his corn liquor by the light of the moon. A speakeasy was an establishment where a patron knocked on the door and whispered the secret code word or the name of a trusted person in order to be admitted. Membership in the KKK grew to more than 100,000 in the state. Crime and Criminals Crime was a big business nationwide in the twenties and thirties. Prohibition had spawned gangs of illegal liquor traffickers and sellers of other vices. Bank robbers blasted their way around the nation, and some of them came from the depressed areas of eastern Oklahoma. George “Machine Gun” Kelly and his wife, Kathryn, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, and Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd all made the most-wanted list of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were killed by law officers, but “Machine Gun” and Kathryn Kelly were captured and convicted of kidnapping Oklahoma City oilman Charles Urschel. They were sent to the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. George “Machine Gun” Kelly Pretty Boy Floyd Bonnie and Clyde The Great Depression On October 29, 1929, the stock market plum meted after a meteoric rise. A record 16 million shares were sold on the stock exchange floor, and stock prices fell an average of 40 points each. The stock market crash is generally considered the beginning of the U.S. plunge into the Great Depression. During the first two years of the Depression, farm prices fell 30 percent, but the taxes the farmers paid and the prices they paid for necessities stayed high. Between 1930 and 1935 more than 750,000 farms were lost through foreclosures and bankruptcy sales nationwide. Governor William H. Murray Although Oklahoma farmers and farmers nationwide were suffering the ravages of depression, William H. Murray believed that the only lasting society was an agrarian society. Alfalfa Bill” Murray believed in the family farm, the yeoman farmer, the values of Thomas Jefferson, and the greatness of the Democratic Party. He believed in equal distribution of arable land (land suitable for raising crops), and he advocated laws to prevent accumulation of large tracts of land by corporations or foreign owners. Murray cont. Without funds, Alfalfa Bill borrowed $40 from a Tishomingo bank and launched a campaign for governor. He toured the state in a used car, stopping to sit curbside, eating his lunch from a paper sack and talking politics with citizens on street corners. He was often unshaven and unkempt, but many unemployed workers and tenant farmers identified with him. William H. Murray advertised himself as “the common man,” a man of the people, and he was elected. He borrowed $250 to attend his own inaugural ball, which was a square dance with the new governor as the caller. Murray cont. Depression conditions were growing worse. Wheat prices dropped from $1 a bushel to thirty-eight cents a bushel. Western Oklahoma depended on the wheat crop. Soon the roads were filled with families moving west — tenant farmers looking for agricultural work. Governor Murray asked for legislative appropriations to furnish free seed and emergency food rations for the needy. Despite his concern for the state’s poor, Murray opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policy and made overt efforts to prevent its coming to the state. Murray cont. William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray was the most colorful, controversial figure in the history of state government. Many loved him. Many hated him. Few were indifferent. He believed in the benefits of an agrarian society to the extent that he rejected industrialization, urbanization, and centralization of governmental power. Yet he wielded the power of the governor’s office more fiercely than any preceding governor of Oklahoma. Although he failed in some areas, he succeeded in making the state government financially sound during the worst economic crisis in national history. The Dust Bowl In 1933 a drought hit western Oklahoma, and with it, the high winds of the Great Plains turned that part of the state and parts of Texas and Kansas into the “Dust Bowl.” Debilitating heat, clouds of sand and dirt, and swarms of grasshoppers and locusts plagued the residents of the Panhandle. Tons of Oklahoma topsoil were carried off by the wind and scattered across the country. Dust Bowl cont. As their forebears had come to the territories seeking a better life, these migrants left Oklahoma in search of a better life. Both desperate and courageous they loaded their belongings and their families onto their vehicles and traveled west in search of jobs they had heard about in the fruitful fields of Arizona, New Mexico, and California. Though many of them were from Arkansas, Kansas, Texas, Colorado, and Missouri, they all became known as “Okies.” The Grapes of Wrath, a novel by John Steinbeck published in 1939, was a best-selling book telling the story of the plight of a migrant family from Oklahoma. Through the popularity of the book, the name Okie became a permanent part of the American vocabulary. Will Rogers and Wiley Post In August, 1935, the deaths of two Oklahomans shocked the nation and especially the state. Will Rogers, an internationally known humorist-actorjournalist, and Wiley Post, an internationally famous pilot, were killed in a plane crash near Point Barrow, Alaska. Wiley Post, in 1933, the first man to fly solo around the world, was the adventurer who had put pride into the hearts of Oklahomans otherwise humbled by the Depression. The state mourned its two favorite sons, and for many, it seemed that the only bright spots of the decade were gone. Woody Guthrie During the years 1936 to 1940, some 309,000 Oklahomans emigrated to other parts of the country in the second stage of the great Okie migration. Ninety percent of them blamed the drought or unemployment for their move. One of the migrants of the thirties was an Okemah folksinger named Woody Guthrie, his folksongs were among the most meaningful in the country’s social history. Composer of “This Land Is Your Land,” “Riding in My Car,” “California Blues,” “Pretty Boy Floyd,” “Tom Joad,” and others, Woody was asked to record his Dust Bowl ballads for the Library of Congress in 1940. Marland administration Ernest W. Marland succeeded Alfalfa Bill Murray in the governor’s mansion. Born in Pennsylvania, Marland had come to Oklahoma and had established an oil empire at one time worth $85 million. With 150,000 Oklahomans unemployed and 700,000 drawing some kind of relief, Marland had devised a state relief aid plan that became known during his campaign as the little new deal WWII and the Division The United States entered World War II during Phillips’s administration, following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Anticipating American involvement in the war, President Roosevelt mobilized the Oklahoma National Guard in 1940. In 1923, when the Guard was expanded to a division, it was designated the 45th Infantry Division. The original insignia for the 45th resembled a gold swastika on a red background — an Indian “good luck” sign. However, when the swastika became infamous as the Nazi symbol with the rise of Adolph Hitler, the original symbol was abandoned. In 1940, the Indian “thunderbird” symbol was adopted in yellow on a red diamond field, and the members of the 45th Infantry became known as the Thunderbirds. th 45 Infantry 45th cont. At one time, American military codes were easily broken by German communications experts, and American soldiers often found themselves stopped by enemy soldiers with advance information. The “codes” of the 45th Infantry Division were never broken, however, because they used communications people who were members of Oklahoma’s Indian tribes. The codes were not codes at all. They were native Indian languages. These men were called “code talkers.” The Thunderbirds were always “gainers,” too. They were the only division that never lost an inch of ground. General George S. Patton, Jr., praised the 45th Infantry with these words: “Born at sea, baptized in blood, your fame will never die. Your division is one of the best, if not the very best, division in the history of American arms.” Governor Robert S. Kerr Oklahoma elected a new governor during the war. Robert S. Kerr, elected in 1942, was the first governor actually born in the state. An attorney and oilman, one of the founders of the Kerr-McGee Oil Company, Kerr was born in a log cabin near Ada in the Chickasaw Nation. Kerr sought to draw industry into the state, and he did a great deal to improve Oklahoma’s image in the nation. Kerr was almost solely responsible for the Arkansas River Navigation Project. This project opened the Arkansas River to handle trade and transport between inland Oklahoma and the Gulf of Mexico.