Salutations: My understanding of 'sustainable development' holds

advertisement

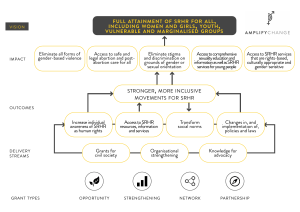

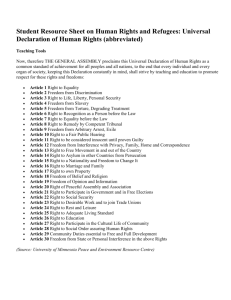

Salutations: My understanding of ‘sustainable development’ holds justice- economic, social, political, reproductive justice at the heart of it- of ‘development justice’. Human rights are at the centre of this and there can be no equivocating on this point. We cannot still be in a place where we barter peoples’ rights and autonomies for oil or trade or for corporate gains or to sustain an inequitable system that favours a select few over the rights of all peoples. To realise a truly just, sustainable future, to truly have youth at the heart of development- as the Bali Global Youth Forum envisioned and attempted to do- we require a radical transformation of the current global, political and economic systems. A strengthened global partnership for development that recognises the common but differentiated responsibilities of countries is also critical. We need an unequivocal commitment to a redistributive framework that targets the reduction of inequalities of wealth, power and resources between countries, between rich and poor, and between men and women. The 1994 ICPD PoA is hailed for heralding a paradigm shift – for putting people and human rights at the centre of development, and reaffirming a comprehensive, inter-sectoral and intersectional approach; placing SRHR and gender equality firmly within the broad development framework. I believe that these are non-negotiable principles for not just SRHR but “sustainable” development as a whole and we must only move forward from here- to actually ensure enabling conditions so people- all people- can claim, exercise, and enjoy all their rights. I think, in this sense, the Bali Global Youth Forum, and the other ICPD review conferences and consultations, including most of the regional consultations, all echo this same vision: a world where everyone’s rights are respected, upheld, and can be exercised Last night, as I was agonising over what to say and how to say it; I was speaking with a colleague about the Global Youth Forum & she asked me what I thought made it so important. The GYF was able to create a safe space for young people from all over the world to discuss, challenge, and sketch out a world that they envision for themselves. The GYF created a space for young people to articulate exactly what the world they envision looks like, to assert themselves- and for me, that’s an immensely important vision. It is essential to acknowledge and understand the diversity of young people and the multiple factors that influence their identities—not just in terms of age, ability, class, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity or expression, citizenship or migrant status, or the languages they speak; and the contexts—cultural, social, religious, political, economic, militarised—that they live in; but in what their experiences are, the access they have to different avenues, and the ways in which negotiating and navigating entrenched, unequal power structures are often a part of their everyday lives. This is something that the Bali Declaration reaffirms consistently – it attempts to understand the contexts that young people live in and offer up recommendations that are relevant to it. It is in this vein that the Declaration offered up a first attempt at defining the ever-evolving concept of ‘family’ beyond the heteronormative, and gender binary imposed norm that has, until now, been seen as a given. It also affirmed young people’s sexuality and pleasure as core rights. It calls for universal access to a basic package of youth friendly health services including mental health care and sexual and reproductive health services, as well as access to safe and legal abortion. The Bali declaration advanced an integrated approach to health and well-being that went beyond the prevention and treatment of diseases alone to focus on the conditions and enabling environments- including comprehensive education, meaningful engagement and civic participation, and employment- necessary for young people to lead healthy lives free from coercion, discrimination, violence and stigma. The Bali Declaration is a reflection not just of the world that young people envision, but the world that they demand. If we are to learn from the lessons of the MDGs, we must ensure that we approach ‘development’ holistically and across the artificial silos of ‘goal one’ and ‘goal two’ and so on- rather than continue to shunt gender equality, SRHR and young peoples’ rights to the margins, they must be seen as centralised; cross-cutting themes, and must be placed within a broader framework that includes fulfilling basic rights to education, health, food, nutrition, housing, livelihood, political participation, and freedom of expression. SRHR, gender equality and equity, and human rights must be recognised as, simultaneously, goals in themselves; as well as essential drivers of sustainable development. . To quote the always-apt Audre Lorde, ‘There is no such thing as single issue struggle because we do not live single issue lives’. We need to ensure that people- especially the most marginalized -can hold governments, corporations, international institutions, donors and other powerholders to account. We must develop accountability mechanisms from the grassroots to the global; we must have strong community and budget monitoring tools to provide input into monitoring mechanisms. The needs and realities of young people vary greatly, and specific interventions that are rooted in their contexts are necessary to address young peoples’ needs. Programmes and interventions that fail to do this, also fail to engage with young people in any real, meaningful and “sustainable” manner, and instead re-etch the same ineffective overwhelmingly patriarchal top-down systems. Understanding the diversity of young people means recognising and respecting their “evolving capacities”, the growth and progression of young peoples’ lives; understanding the impact of their contexts on their access to services, information, and the conditions under which they make their “choices”- this is crucial for young peoples’ rights and for any sincere attempt at sustainable development. This the only way forward towards a future that young people not only want and desire, to one that is just; but one that they have full ownership over.