SeanFinalProjectDraft2

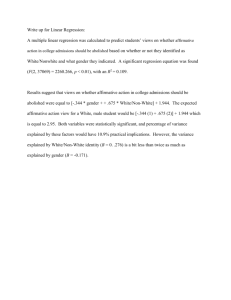

advertisement

Running head: AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND NORTEASTERN UNIVERSITY Final Project by Sean O’Connell EDU-7253 The Legal Environment of Higher Education 12/5/13 1 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 2 Abstract This field project looks at the issue of affirmative action, and, more specifically, affirmative action within the context of a non-profit, private, urban university: Northeastern University. The researcher mined information about affirmative action from government documents, scholarly journals, and law journals. Moreover, for information about Northeastern University, the researcher relied on websites, books, and interviews with Northeastern University employees, both former and present. The project concludes that despite high-profile law cases that have threatened some universities’ affirmative action efforts, affirmative action endeavors on the part of higher education institutions are often legal, and, more importantly, necessary, in creating a more just society, and this was found to be true for Northeastern University. Keywords: affirmative action, diversity, Northeastern University AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 3 Affirmative Action and Northeastern University Affirmative action was created with intentions of, among other things, granting more people of color admission to American universities. Today, however, it is sometimes the center of controversy. Those who support it argue that it helps to right the wrongs that have been done to people of color throughout American history, and that a more diverse student body leads to better educational outcomes and learning experiences for all students. Those who oppose it, in many cases, see it as being reverse discrimination; that is, they argue that this policy, though meant to curb discrimination, actually employs it by denying qualified students admission to colleges while less qualified students are admitted based on their race or ethnicity. Regardless of one’s personal views of the merits of affirmative action policies, it is clear that the practice can elicit strong emotions from the general public, and in some cases the issue has been the center of highly-publicized court cases at the state and federal level. Although not the target of any high-profile litigation cases over unfair affirmative actionrelated issues, Northeastern University, the subject of this case study, is reflective of affirmative action law and the way it’s evolved throughout the years. It has tried to adhere to the rules of law regarding affirmative action, from implementing the policy to attain a more diverse student body in the wake of civil rights legislation, to not relying solely on students’ races or ethnicities, lest the college be the target of a lawsuit today. With the institution currently recruiting a breadth of students from different backgrounds – racially, ethnically, economically, geographically, etc. – and becoming a more elite institution in terms of its admission requirements, the issue of affirmative action is still very pertinent, and it is important to consider warranted actions – those already in place and those that should be in place in the future – to ensure that its measures work effectively. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 4 Causes and/or Antecedents On a Macro Level Sadly, much of the economic growth and development in America prior to the Civil War resulted from its use of slave labor, a practice that denied a segment of the country’s population one of its most inherent values: freedom. Even after the end of the war and emancipation of slaves, the country continued to make discrimination against black legal via the Jim Crow Laws, unjust laws that pervaded for about a century. It was not until Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al. (1954) that public school segregation was declared to be illegal, and the already-burgeoning civil rights movement for people of color gained even more momentum. Soon thereafter, affirmative action policies in the wake of the 1964 Civil Rights Act required that universities level the playing field for their admissions policies; thus, many institutions made a concerted effort to admit more students of color, and indeed, according to law, they had to. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act required colleges to follow federal guidelines and show proof that they were acting within the law, hence admitting a higher number of students of color (Kaplin & Lee, 2007; Northeastern University, 2013b). In this way, most American colleges, Northeastern included, were required to reach out to underrepresented student population; there was no debate or controversy surrounding affirmative action policies at this time in American history. It was simply the law. However, later high-profile court cases, namely at public institutions where plaintiffs claimed that their rights were violated under the Equal Opportunity Clause, helped to ignite controversy surrounding the issue of affirmative action (Kaplin & Lee, 2007). For instance, the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) centered on a white male who applied to AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 5 the University of California at Davis’ medical school. After being denied, he filed suit, alleging that the university, which had a policy of admitting a certain number of students of color, discriminated against him based on his race. When the case reach the U.S. Supreme Court, it found that though some affirmative action programs, such as the quota system used by the UC Davis, are unfair, taking race into consideration for admissions is permissible when it’s considered as just one of many qualities that are reviewed by admissions personnel, and that a diverse student body is beneficial to a college and its students. Similarly, two seminal affirmative action cases in the context of college admissions at state universities took place in 2003, both involving the University of Michigan, and they essentially affirmed the rulings in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978). In Gratz v. Bollinger (2003), a case that centered on a white student being denied admission to the university as an undergraduate, the plaintiff accused the university of discriminating against her because it assigned points to applicants who were students of color. These points then put those students at an advantage when compared to other, non-minority students. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that, like Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), Gratz v. Bollinger (2003) demonstrates an unfair use of race in admissions, and that it violates students’ rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The other case at the University of Michigan, Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), focused on admissions of students to the university’s law school, and the university was once again accused of unfairly admitting students based on their race. In this case, however, the Supreme Court ruled that race was a fair and admissible factor to consider in admissions because the law school did not rely on a quota or points system in its admitting students of color. Instead, it considered race and ethnicity as one of a number of factors in reviewing student applicants, and in this way, AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 6 its review of applicants was holistic in nature. Moreover, the Court found the university’s argument – that a diverse student body is of great value to student growth and learning – to be compelling and convincing. In short, the Court deemed that a holistic approach to admissions and an argument focused, in part at least, on student diversity is strong; hence, affirmative action was found to be lawful in this instance. Lastly, the most recent affirmative action case to garner nationwide attention happened in the summer of 2013. In this case, Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (2013), a student denied admission to the university again accused it of unfair affirmative action practices. While no decisive decision resulted – the case was remanded for further review – it did show that the Supreme Court would not tolerate lower courts haphazardly skimming the details in cases such as these. In fact, the Supreme Court argued that the University of Texas at Austin’s affirmative action policies must be subject to “strict scrutiny” to ensure that they don’t discriminate against students who would not be traditionally aided by affirmative action efforts. The insistence that “strict scrutiny” be used shows the Supreme Court’s acknowledgement that the issue is serious and deserving of special attention. On a Micro Level In terms of affirmative action’s role within the history of the university that is the subject of this field project, Northeastern University, it came to prominence primarily as a result of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, which demanded, “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance” (Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act). Although the university was founded on AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 7 democratic principles – after all, unlike many traditional colleges in the Boston region where students would room and board full time on a college campus, Northeastern was founded with a mission to provide a part-time education to working people who would take night classes in the Huntington Avenue YMCA (Northeastern University, 2013b) – it didn’t have a racially diverse student body for most of the early to mid-20th century. However, because of the 1960’s cultural and political movements towards providing the country’s people of color with more opportunities, as well as new requirements to adhere to the law, Northeastern did begin to make a strong effort to create a pluralistic student body. For example, in 1966, only 2.7% of the population was black, but this number increased to 10.6% of the student population by 1971, as the university worked to comply with federal civil rights legislation (Frederick, 1982). During the 1970’s, outreach to students of color from Boston continued. Scholarships were made available to students who were deemed as having successful experiences in Balfour Academy, a summer program for middle school and high school students from Northeastern’s surrounding neighborhoods, such as the Fenway, Roxbury, and Mission Hill. Furthermore, the university worked in concert with the Boston Housing Authority, offering up to sixty scholarships for highly qualified students who lived in public housing (Frederick, 1995). In general, the 1970’s were viewed as a time in which affirmative action was greatly emphasized at Northeastern. President Asa Knowles established an affirmative action office on campus, designed to adhere to federal laws that required institutions to maintain equity in their hiring of personnel and admission of students. Moreover, his administration founded the university’s African-American Institute, a platform through which students could learn about and embrace African-American culture. Knowles was succeed by President Kenneth Ryder, who continued to AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 8 make affirmative action a priority and who hired two prominent African-American civic leaders in the city, Ellen Jackson and John O’Bryant, to head the African-American Institute and division of Student Affairs, respectively (Frederick, 1995). Following the lead of President Knowles’ and President Ryder’s strong support for affirmative action, John Curry, the university’s president from 1989-1996, continued to prioritize making Northeastern a welcoming and inclusive environment for people of diverse backgrounds. Among other things, Curry commissioned an on-campus study of how to reduce “intolerance and discrimination,” he created an ombudsman position to oversee the recruitment of diverse faculty and students, he established an executive board that would focus solely on issues of campus diversity, and he founded eight scholarships that would be reserved for students of Hispanic and Latino heritage (Feldscher, 2000, p. 157). And President Curry’s successor, Richard Freeland, continued to closely monitor the campus climate in regards to diversity, administering studies on the topic, creating job opportunities solely for minority candidates, hiring a head for the Institutional Office for Diversity and Inclusion who would embrace the spirit of diversity and do so in a positive light, and setting targets for admitting students of color and students from lowincome families (R. Freeland, personal communication, November 5, 2013). All of Northeastern’s efforts to comply with affirmative action standards are impressive, and some might even say that Northeastern has traditionally been an institution to welcome a wide-range of students. Still, one has to wonder how its affirmative policies have been shaped as a result of the intense debates and legal outcomes in recent years surrounding affirmative action at the national level. Have these controversies swayed Northeastern to reshape or revise any of its policies? Have they cut any or, conversely, added new ones? Grodsky and Kalogrides (2008) observe, “As the legal environment changes, or even as it is perceived to change, risk-adverse AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 9 institutions may simply abandon or repackage their affirmative action programs to avoid scrutiny” (p. 27). Indeed, one wonders what Northeastern has done over the years to either maintain or minimize its affirmative action endeavors; one of the central purposes of this field was to address this question. Data Collection The data collection for this case study was based on a number of sources of information. First, the author consulted government websites to gain a better understanding of federal laws that made affirmative action programs – both in terms of job hiring and student admissions – a priority in this country. It was essential that the researcher gain a historical perspective on how this issue came about and how it developed over time. Second, the author consulted academic journal articles that focused on the idea of affirmative action. Scholarly sources, such as American Journal of Education, Political Research Quarterly. Research in Higher Education, and Sociology in Education, were helpful in providing a better understanding of the arguments surrounding affirmative action. They showed that the issue is tied not only to America’s higher education system, but to the collective conscious of most Americans – their views on American history, politics, and culture – and the consequences of living in a country in which a significant proportion the country’s ancestors was once legally enslaved, and, even after becoming emancipated, legally disenfranchised. Third, the law journals – for example, Stanford Law Review, Boston College Law Review, Northern Illinois University Law Review, etc. – gave a thorough analysis of some of the seminal court cases focusing on affirmative action. Though most of the authors of these articles were in favor of affirmative action, and thus not providing much information about why such policies AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 10 should be challenged or rejected, they did critique some of the reasoning used by parties involved in court cases as well as court judgments themselves. Detail-oriented law reviews pointed to how affirmative action has evolved over the years, and how universities must use it in ways that keep them safe from prosecution while still adhering to ethical and legal principles about access and equality. Lastly, Northeastern University archives and books, as well as interviews with former and current university employees, helped to illuminate the issue of affirmative action within the context of a single higher education institution. The archives provided sound information about university changes in admissions and hiring practices in the wake of civil rights legislation. They also pointed to how campus leaders played a role in trying to make the university a more diverse community. As for personal interviews, speaking with employees – for example, Molly Dugan, the director of the Foundation Year program, or Brian Murphy-Clinton, Executive Director of Enrollment in the College of Professional Studies – demonstrated how affirmative action plays a role at Northeastern and, more specifically, within Northeastern University’s College of Professional Studies and the Foundation Year program which is housed there. Warranted Actions Actions Already in Place Based on the research conducted for this case study, it’s become clear that Northeastern University is conscientious about maintaining fair admissions policies and fostering policies that will yield a pluralistic student body. As stated on its webpage for potential applicants, the university aspires to “build a diverse community of bright, mature, and highly curious students who are a good match for our distinctive educational experience” (Northeastern University, AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 11 2013a). In trying to achieve this diverse student body, while also, one would assume, trying to avoid litigation about discriminatory admissions processes, it uses a variety of techniques. First, according to Brian Murphy-Clinton, Executive Director of Enrollment in the College of Professional Studies, students applying to the university as freshman are asked to supply a written answer to a question about their “commitment to diversity” (B. Murphy-Clinton, personal communication, October 22, 2013). In this way, students are evaluated not based on their own respective race or ethnicity, but rather on their attitudes towards the concept of diversity and how they value it in their lives. According to Murphy-Clinton, from the perspective of Northeastern admissions staff and administrators, a diverse student body is not narrowly defined as just students from different racial or ethnic backgrounds. Rather, today it can also be defined by students’ sexual orientations, gender identifications, and physical or mental disabilities. Furthermore, because the university has rapidly climbed the rankings of competitive American universities in recent years and hence has record numbers of applicants, it also can define diversity in terms of where students hail from geographically, whether different regions of the United States or even different countries from throughout the world (B. MurphyClinton, personal communication, October 22, 2013). Second, although the term “affirmative action” is not used in recruitment literature and recruitment literature does not explicitly state that the university seeks students of color or of various ethnic backgrounds, there are still some programs on Northeastern’s campus that end up serving a high percentage of minority students. For example, the Torch Scholar Program aims to recruit and admit qualified students who have “overcome exceptional odds,” and the mission of the program centers on “closing the achievement gap for first-generation, low-income students from diverse backgrounds” (Northeastern University, 2013d). This program admits about a AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 12 dozen students per year and recruits them from locales throughout the country. Most of the students are highly qualified in terms of their academic preparation for college, but personal finances or family circumstances might hinder their success in traditional college settings; hence, the program offers a variety of supports to help these students enroll in Northeatern, and then persists and succeed while there. Again, while the program does not specifically target students of color, the majority of the students fit this category. Similar to the Torch Scholars Program, but on a larger scale and housed solely within the university’s College of Professional Studies, is the Foundation Year program, a program that aims to improve the college persistence rates among students who attended high school in Boston. This endeavor was initiated as a result of a study done by Northeastern’s Center for Labor Market Studies, which found that students from Boston high schools were entering college at high rates but persisting and graduating from college at low ones. To be more specific, the 2008 longitudinal study found that among Boston Public School (BPS) graduates from 2000, only 40% of them had earned a two-year or four-year degree by the summer of 2007 (Northeastern University Center for Labor Market Studies, 2008). Worried about these findings, Boston area politicians, business leaders, and educators made it a priority to improve the college retention and graduation rates for students from Boston. Consequently, Northeastern created Foundation Year. Admissions to Foundation Year are dependent on various factors, but the sole constant among all of those admitted is that they must have attended a Boston school – whether public, parochial, or private – and that they have attained a high school diploma or GED. In this sense, the program acts like a community college, but one situated within a four-year institution. Furthermore, the program was founded with a funding model that would combine federal, state, AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 13 and university funds in meeting the financial needs of all accepted students, and nearly all of the students who attend pay little to nothing out of their own pockets. Nowhere in the Foundation Year informational literature is there a mention of actively recruiting students of color. Yet when considering that most of the students come from within the city and that most of them are in need of significant financial aid assistance, it’s a given that the majority of the students will be students of color, as this demographic of the city of Boston’s population comprises a higher proportion of low-income residents. As Foundation Year faculty member Peter Plourde describes: “Though the goal of Foundation Year was to improve the city’s college graduation rate of students from BPS, it indirectly also serves to bolster the rate of minority students on campus since BPS is mainly servicing a minority population largely reflective of the Roxbury/Mission Hill neighborhood it is situated within” (P. Plourde, personal communication, October 7, 2013). In this way, the program could be considered an affirmative action program, though once again it doesn’t explicitly say so in the literature it provides online or in hard copy form. Foundation Year Director, Molly Dugan, however, is more frank in her opinion about the program’s place in the context of affirmative action. When asked directly if asked if Foundation Year is an affirmative action program, she replied, “I believe we could say that Foundation Year is illustrative of affirmative action, because we have the mission of improving the educational opportunities of students from Boston, most of whom are from minority racial and ethnic groups” (M. Dugan, personal communication, October 22, 2013). Important to understand is that even though Foundation Year has a targeted student population – again, students who attended high school in Boston and earned a diploma or GED – and this population is largely comprised of students of color, the program reviews applicants in a holistic manner, and considers many of the traits and characteristics that students bring with AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 14 them, not solely their racial or ethnic background. Because of this holistic and flexible admissions process, Foundation Year, and programs of similar ilk, should be safe from accusations of reverse discrimination because they’re very individualized in their admission of students, not necessarily tied to quotas or points systems based on applicants’ race or ethnicity (Devins, 2003; Poreda, 2013). Also noteworthy is that Northeastern has an Office of Institutional Diversity and Inclusion. According to its website, its main objective is to foster the “university’s commitment to equal opportunity, affirmative action, diversity, and social justice while building a climate of inclusion on and beyond campus” (Northeastern University, 2013c). Nevertheless, the office caters more towards affirmative action in the context of employment, and as for students it centers more on students who’ve already been accepted and how they can experience and celebrate diversity on campus. Nowhere on the site does it mention affirmative action as an admissions strategy. To summarize, while Northeastern programs such as the Torch Scholars and Foundation Year don’t explicitly state that their purpose is to recruit and serve students of color, they do so through different means: Foundation Year does so by recruiting students from a certain geographic location, Boston, and the Torch Scholars program does so by recruiting students who have shared a similar experience, overcoming significant obstacles in their life. Actions that Should be Put in Place If Northeastern is intent on avoiding reverse discrimination accusations of unfairly admitting students of certain races and ethnicities, they could use an alternative means of recruiting and admitting students, doing so based on students’ socio-economic backgrounds. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 15 This type of socio-economic targeted admissions effort is in keeping with proponents of classbased admissions, who argue that because many minorities have disproportionately low incomes, colleges can open their doors to low-income students and hence increase their number of students of color admitted (Young & Johnson, 2004). To some degree, part of Foundation Year’s mission, which is to provide significant portions of financial aid to students so that students’ lack of economic resources is not a barrier to their pursuit of a college degree (B. Murphy-Clinton, personal communication, October 25, 2013), does fulfill the concept of targeting students and creating a diverse student body based on economics. One would assume that other colleges within the Northeastern University have similar admissions goals and processes, but if not, this is certainly one way the university could create a more diverse student body. Furthermore, in striving for a diverse student population Northeastern could also target students from varied geographic locations. Alon (2011) and Bibbings (2006) argue that selection of students for admission can be tailored based on students’ geographic locales, and in doing so make a university have a more diverse student body in a given class of incoming freshmen. Once again, Foundation Year, and its focus on students who are from Boston, demonstrates how geography can be another way to increase student diversity. Although this researcher asked a senior member of Northeastern’s “day school” admissions staff for an interview, the request was denied, and thus it’s uncertain how other Northeastern University colleges, besides the College of Professional Studies, review their applicants. But if the day school’s admissions staff is given the benefit of the doubt, one would assume that this selection process is very methodical and fair to all student applicants. If not, however, those colleges will need to be careful about how they shape their admissions processes AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 16 so that selection of students is holistic, thoughtfully considering each student as an individual, lest they face lawsuits and undergo strict scrutiny by the courts (Green, 2004; Kim, 2005). Indeed, affirmative action programs need to frequently evaluate and then reevaluate their own admissions policies to make sure they’re conforming to the law, while also reaching their full potential in working effectively with a wide-range of students (Cordes, 2004). Perhaps because Northeastern does not explicitly name race or ethnicity as factors considered for admission, it avoids accusations of reverse discrimination in the name of affirmative action. Nevertheless, the absence of a clear mission in aiding students of certain races and ethnicities is troubling to some scholars who argue that relying on a model of admissions that emphasizes socio-economic status or students’ geographical background ignores the original, and paramount, reason for the establishment of affirmative action in the first place – that of social justice, and a system that’s trying to make amends for an ugly, unjust history of institutional racism (Anderson, 2007; Beauchamp, 1997; Finnie, 2008). To put it another way, a system of affirmative action based solely on students’ socio-economic stature or geographic locale could have the effect of ignoring or eliminating the idea that it’s important to help America’s people of color, people who have traditionally been underserved and the targets of unjust discrimination. Because of this fear that affirmative action policies are digressing too far away from their original intent, these critics would argue that programs should not be reticent about touting their social justice missions (Greenberg, 2002; Marable, 2005; Tierney, 2007). Given the criticism from some who feel that colleges have wrongly moved their affirmative action goals away from their focus on students of color, Northeastern, with its proud heritage of being a university that serves urban, working people, perhaps should be less cautious and subtle about its aims to serve students of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. In contrast AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 17 to its nuanced approach for creating a pluralistic student body, maybe it should be explicit in stating its goals, and in this way appease those who feel that affirmative action policies have been watered down since originally implemented. Northeastern University education professor, Lula Petty-Edwards, a faculty member for almost thirty years and an African-American woman raised in the Jim Crow south, feels that the university’s current climate surrounding affirmative action is “symbolic, but not substantive” (L. Petty-Edwards, personal communication, October 4, 2013). Likewise, other critics might feel the same way; thus, the university may want to address the issue of affirmative action in a more transparent manner. Indeed, if the university was to return to a campus climate where affirmative action was spoken about in a more explicit manner, where it was discussed in the context of recruiting students of color and of different ethnic backgrounds, then it would be important to hold discussions among students about the issue of affirmative action. Some researchers have studied college students’ perceptions of the term, and in this research found that white male students accounted for the most negative criticism of affirmative action practices compared to their peer groups (Zamani-Gallaher, 2007), but this doesn’t mean that they’re the sole critics of this practice, nor does it mean, of course, that all white males are opposed to affirmative action to begin with. In fact, one has to consider whether students of color, students who traditionally have benefitted from affirmative action in the past, feel that the practice can stigmatize them as students who were unfairly admitted to a college. In addition, it’s important to note that one’s views of affirmative action may evolve over the course of his or her college tenure. For instance, Park (2009) supports the notion that students’ views on affirmative action may change over time, and says this happens in large part because during college students are “taking new information and forming new opinions about the nexus of race and politics” (p. 668). With this theory in AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 18 mind, one sees how students’ perceptions of affirmative action may change over time, and how the discussion of affirmative action can lead to profound learning experiences for said students. Additionally, if the university had more candid discussions about affirmative action in the context of race and ethnicity, it could emphasize the benefits of students learning in a diverse population. Indeed, many of the Supreme Court’s findings in high-profile affirmative action cases have supported the idea that a diverse student body is of great value to student learning (Anderson, 2007; Bakken, 2004; Green, 2004; Poreda, 2013). This being the case, the university could use these findings and the research of scholars who are experts on this issue as support for having a diverse student body, and, as a result, be more explicit in its aspirations to recruit more students of color and different ethnicities. In fact, those who oppose affirmative action policies should recognize that the reduction of affirmative action programs would not only harm students of color, because fewer of these students would conceivably be admitted to competitive institutions (Cortes, 2010; Pidot, 2006), but would also harm white students because they’d, in turn, be exposed to a less diverse student body and the heterogeneous viewpoints and experiences that come with this mix of students (Bakken, 2004; Mortin, 1997). Lastly, it’s crucial to note that despite criticism on behalf of those who feel that affirmative action practices should be more pervasive today, the absence of the term “affirmative action” in student recruitment and admissions literature at Northeastern and other universities does not necessarily suggest these universities are omitting these terms for purely legal purposes, nor does it suggest, once again, that affirmative action is necessarily absent in these institutions. In fact, Richard Freeland – a higher education scholar, the president of Northeastern from 19962006 , and the current Commissioner of the Board of Higher Education of Massachusetts – AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 19 claims that the term “affirmative action” essentially shifted to “diversity” as a result of the culture of American higher education institutions, not for legal or political reasons (R. Freeland, personal communication, November 5, 2013). In other words, on the heels of the civil rights movement of the 1960’s and the multicultural movement that followed it, colleges and universities strived to create campuses were students from different backgrounds would feel welcome and where colleges could proactively celebrate students’ differences in culture. In this way, the move away from the term “affirmative action” was less of a change made in order to avoid litigation, and more so a concerted effort to embrace a more welcoming term that represented colleges’ goals to encompass a range of students from different backgrounds (R. Freeland, personal communication, November 5, 2013). Conclusion America is a diverse, multicultural society today and it’s continuing its trajectory in this direction. Within the next half century, the population of whites will decrease, while the population of blacks will increase by 50% and the number of Hispanics in the country will double (United States Census, 2012). In fact, as the demographics continue to shift, many predict that the nations will soon be comprised of a “minority majority,” meaning that those once considered “minorities” will make up most of the population while whites citizens will become the minority. Therefore, affirmative action programs, if continued to be found legal and just, must work more effectively while demographic changes occur and better educate all American students so that they’re able to participate in a democracy and compete economically with people from around the world (Alon & Tienda, 2005; King, 2005; Mortin, 1997). AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 20 Perhaps the most pertinent questions to consider today are: What will public perceptions of affirmative action be like in the future and will these types of programs continue to be lawful? It seems that most well-reasoned people, whether pro-affirmative action or anti-affirmative action, have a similar goal for the future, which is that affirmative action will no longer be necessary. In other words, these people would hope racial and ethnic disparities in jobs and college admissions would decrease, and applicants would be considered fairly, regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds. Indeed, the Supreme Court has said as much – see, for example, Gratz v. Bollinger (2003) and Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) – arguing that affirmative action practices in college admissions should be a temporary measure, one that should end at some point. And this tension about when it should end is at the crux of the debate. On the one hand, some think it should end immediately because contemporary higher education provides many opportunities for students to pursue a college degree, and for those who are applying to competitive universities, they should all be treated fairly by college admissions teams, judged on their merits, regardless of race. On the other hand, there are those who feel that contemporary society, though certainly offering more opportunities to people of color and treating them more fairly in the past, is still comprised of subtle forms of institutional racism and unfair discrimination; consequently, they feel that those who are from underrepresented populations should be given a slight advantage in their pursuits of a college degree. Obviously, the culture of the nation, its politicians, and those serving on the Supreme Court at a given time will have a big impact on the future of affirmative action. Nevertheless, the culture of the nation’s colleges in the future – their students and personnel (e.g., administrators, faculty, and staff) – should have the greatest impact on what affirmative action looks like years from now and how it’s perceived by the public. In many of these higher education contexts, affirmative action is perceived in a AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 21 positive light and deemed by many as a necessity (Lipson 2009). The term may have changed in recent years – true, today it’s more common to hear about colleges touting their “diversity” than their “affirmative action” practices – but it remains a significant value for most colleges, and this is certainly true in the case of Northeastern University. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 22 References Alon, S. (2011). The diversity dividends of a need-blind and color-blind affirmative action policy. Social Science Research, 40(6), 1494-1505. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.05.005 Alon, S., & Tienda, M. (2005). Assessing the "mismatch" hypothesis: Differences in college graduation rates by institutional selectivity. Sociology of Education, 78(4), 294-315. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org Anderson, J. D. (2007). Past discrimination and diversity: A historical context for understanding race and affirmative action. Journal of Negro Education, 76(3), 204-215. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org Bakke v. Regents of University of Cal, 438 U.S. 265 (1976) Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Beauchamp, T. L. (1998). In defense of affirmative action. The Journal of Ethics, 2(2), 143-158. Bibbings, L. S. (2006). Widening participation and higher education. Journal of Law & Society, 33(1), 74-91. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6478.2006.00348.x Cortes, K. E. (2010). Do bans on affirmative action hurt minority students? evidence from the texas top 10% plan. Economics of Education Review, 29(6), 1110-1124. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.004 Daneil Bakken, The Supreme Court Strikes down the University of Michigan’s Admission Policy but Finds Diversity to be a Compelling Interest, 80 N. Dak. L. Rev. 289 (2004). Retrieved from http://lexisnexis.com Devins, N. (2003). Explaining grutter V. bollinger. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 152(1), 347-383. Retrieved from http://0-ehis.ebscohost.com AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 23 Feldscher, K. (1995). Northeastern University, 1989-1996: The Curry Years. Boston: Northeastern University. Frederick, A. (1982). Northeastern University: An Emerging Giant, 1959-1975. Boston: Northeastern University. Frederick, A. (1995). Northeastern University, Coming of Age: The Ryder Years, 1975-1989. Boston: Northeastern University. Finnie, S. (2008). The debate over class-based versus raced-based affirmative action in higher education. Journal of Intercultural Disciplines, 8, 181-191. Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, 133 S. Ct. 2411 (2013) Grodsky, E., & Kalogrides, D. (2008). The declining significance of race in college admissions decisions. American Journal of Education, 115(1), 1-33. 152(1), 347-383. Retrieved from http://0-ehis.ebscohost.com Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003) Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) Jack Greenberg, Affirmative Action in Higher Education: Confronting the Condition and Theory, 43 B.C.L. Rev 521 (2002). Retrieved from http://lexisnexis.com Jeramy Green, Affirmative Action: Challenges and Opportunities, BYU Educ. & L.J. 139 (2004). Retrieved from http://lexisnexis.com Justin Pidot, Intuition or Proof: The Social Science Justification for the Diversity Rationale in Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger, 59 Stan. L. Rev. 761 (2006). Retrieved from http://lexis.nexis.com Kaplin, A. & Lee, B. (2007). The Law of Higher Education 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 24 Kim, J. K. (2005). From bakke to grutter: Rearticulating diversity and affirmative action in higher education. Multicultural Perspectives, 7(2), 12-19. doi:10.1207/s15327892mcp0702_3 King, D. (2005). Facing the future: America's post-multiculturalist trajectory. Social Policy & Administration, 39(2), 116-129. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2005.00429.x Linda Mortin, Affirmative Action in the University of California Admissions: An Examination of the Constitutionality of Resolution, 19 Whittier L. Rev. 373 (1997). Retrieve from http://lexisnexis.com Lipson, D. N. (2011). The resilience of affirmative action in the 1980s: Innovation, isomorphism, and institutionalization in university admissions. Political Research Quarterly, 64(1), 132-144. doi:10.1177/1065912909346737 Marable, M. (2005). The promise of brown: Desegregation, affirmative action and the struggle for racial equality. Negro Educational Review, 56(1), 33-41. Mark W. Cordes, Affirmative Action After Grutter and Gratz, 24 N. Ill. U. L. Rev. 691 (2004). Retrieved from http://lexis.nexis.com Michael Poreda, Perspectives on Fisher v. University of Texas and the Strict Scrutiny Standard in the University Admissions Context, BYU Educ. & L. J. 319 (2013). Retrieved from http://lexisnexis.com Northeastern University (2013a). Admissions. Retrieved from http://www.northeastern.edu/# Northeastern University (2013b). Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. Retrieved from http://library.northeastern.edu/archives-special-collections/findcollections/northeastern-university-archives-and-history Northeastern University (2013c). Office of Institutional Diversity and Inclusion. Retrieved from AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 25 http://www.northeastern.edu/diversity/ Northeastern University (2013d). Torch Scholars Program. Retrieved from http://www.northeastern.edu/torch/ Northeastern University Center for Labor Market Studies (2008). Getting to the Finish Line College Enrollment and Graduation: A Seven Year Longitudinal Study of the Boston Public School Class of 2000. Retrieved from http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/news/ mayor-menino-double-college-graduation-rate-boston-students Park, J. J. (2009). Taking race into account: Charting student attitudes towards affirmative . Research in Higher Education, 50(7), 670-690. Tierney, W. G. (2007). Merit and affirmative action in education. Urban Education, 42(5), 385402. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (2013). Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/cor/coord/titlevistat.php United States Census. (2012). U.S. Census Bureau Projections Show a Slower Growing, Older, More Diverse Nation a Half Century from Now (CB12-243). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/Newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html Young, J. W., & Johnson, P. M. (2004). The impact of an ses-based model on a college's undergraduate admissions outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 45(7), 777-797. Zamani-Gallaher, E. (2007). The confluence of race, gender, and class among community college students: Assessing attitudes toward affirmative action in college admissions. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40(3), 241-251. doi:10.1080/106656807