jkw_gws_2015

advertisement

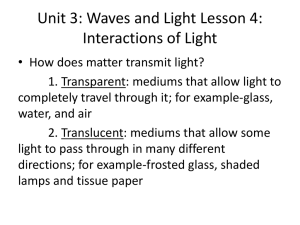

Why search for GWs? • • • • New tests of general relativity Study known sources – potential new discoveries that are inaccessible using EM View the universe prior to recombination. Observe T=0? The ultimate naked singularity? Because it’s fun (besides, Einstein said it’s worth doing!) 5695 papers with the words “Gravitational Waves” in the title, 2004-2014 http://science.gsfc.nasa.gov/663/images/gravity/GWspec.jpg http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html GW Sources: Relic background: A stochastic signal from the Big Bang itself, this consists of quantum fluctuations in the initial explosion that have been amplified by the early expansion of the Universe. While the spectral shape of this source can be predicted, its overall strength is highly uncertain, but is constrained by the fact that gravitational wave perturbations are one of several components contributing to the observed temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. This limits the maximum strength of gravitational waves at cosmological length scales. Two curves are shown: one at the upper limit of the observational constraints, and another an order of magnitude weaker. Binary background: Another stochastic signal, this one arising from thousands of binary systems emitting gravitational waves continuously in overlapping frequency bands. The individual signals are unresolveable. At long wavelengths (larger than 1014m), the binaries in question are pairs of supermassive black holes (millions of times the mass of the Sun) orbiting in the centers of galaxies. The hump at shorter wavelengths (1013 to 1011m) is contributed by binary white dwarf stars within our own Galaxy. SMBHB (Super-Massive Black Hole Binaries): Occasionally, one of the supermassive black hole systems mentioned above will merge, producing a huge burst of gravitational waves at millihertz frequencies. Such bursts would be detectable throughout most of the known Universe, though the rate is highly uncertain: one per year is an optimistic estimate. http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html GW Sources: WDB (White Dwarf Binaries): Above the white dwarf stochastic background are a few thousand individually-resolveable white dwarf binary systems in our Galaxy. Some of these systems have already been charted with conventional astronomy, and thus would be known callibrators for future gravitational-wave detectors. EMRI (Extreme-Mass-Ratio Inspirals): These are compact stellar remnants (white dwarfs, neutron stars, or stellar-mass black holes only a few times more massive than our Sun) in the process of being captured and swallowed by a supermassive black hole (millions of times more massive than the Sun). BHB (Black Hole Binaries): These are binary systems consisting of two stellar-mass black holes (a few times the mass of the Sun). NSB (Neutron Star Binaries): These are binary systems consisting of two neutron stars. NS (Neutron Stars): This refers to the gravitational waves generated by individual neutron stars as they spin. In order to generate gravitational waves, the neutron star must deviate from pure axisymmetry. Several mechanisms have been proposed for generating or sustaining such asymmetries, but their magnitudes are highly uncertain; the plot indicates some optimistic upper limits. http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html GW Detectors: Cosmic microwave background: Several thousand years after the Big Bang, when the hot plasma of protons and electrons cooled and combined to form the first atoms, electromagnetic radiation was released into the newly-transparent Universe. Today, this cooled and redshifted radiation is seen as a pervasive microwave background. Density fluctuations in the plasma resulted in small fluctuations in observed temperature across the sky, but long-wavelength gravitational waves will also contribute their own perturbations to the spectrum. At present these contributions are difficult to separate out, so the total observed fluctuations place an upper limit on the size of gravitationalwave fluctuations. http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html GW Detectors: Pulsar timing: Pulsars are spinning neutron stars that emit beams of electromagnetic radiation, seen as "pulses" when they sweep over the Earth. Since the spin of a neutron star is very stable, these pulses can be predicted and fit with high precision. A passing gravitational wave alters the path length between the pulsar and the Earth, changing the pulse arrival times in a fluctuating manner. The lack of such fluctuations can be interpreted as an upper limit on gravitational waves that have wave periods shorter than the total duration of the pulse observations (years or decades). A gravitational wave could be detected if two or more pulsars show a correlated pattern of fluctuations in pulse arrival times. http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html Detectors: LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory): This consists of two facilities in separated locations in North America. Each facility has an L-shaped vacuum tube 4 kilometres long, with masses hanging at the corner and ends of each arm, carefully shielded against vibrations or other outside disturbances. A passing gravitational wave changes the relative distances between the masses in the two arms, which can be detected by interfering laser beams traveling along each arm. Present-day sensitivity is at a level where detection of gravitational waves is plausible, if not likely. http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~teviet/Waves/gwave_spectrum.html Gravitational waves from inflation generate twisting pattern in the polarization of the CMB, known as a "curl" or B-mode pattern. Shown here is the actual B-mode pattern observed with the BICEP2 telescope, with the line segments showing the polarization from different spots on the sky. The red and blue shading shows the degree of clockwise and anti-clockwise twisting of this B-mode pattern. (BICEP2 Collaboration)