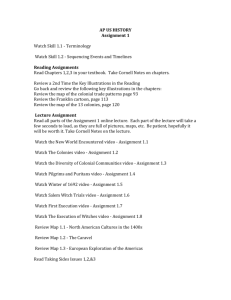

Fall 2014 Syllabus - Faculty

advertisement

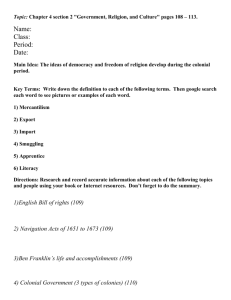

1 HISTORY 303—COLONIAL AMERICAN HISTORY, 1607-1763 Fall 2014 Vivian Bruce Conger 408 Office Hours: MW 2:00-4:00 p.m., and by appointment Office phone number: 4-3572 Office: Muller e-mail: vconger@ithaca.edu “Popular history, and also the history taught in schools, is influenced by this Manichaen tendency, which shuns half-tints and complexities; it is prone to reduce the river of human occurrences to conflicts, and the conflicts to duels—we and they, the good guys and the bad guys respectively, because the good must prevail, else the world would be subverted.” Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (1989) Course Description: Through discussion, this course examines the complex relationship between a wide range of people and institutions in early America from initial settlement to the eve of the American Revolution (it stops with the conclusion of the Seven Years War in 1763). By exploring the many ways in which people interacted with each other and with other groups of people, you will gain a better understanding of the foundations upon which Spanish, French, Dutch, and English colonists settled North America. In addition, you will gain an appreciation of the historical process by looking at the questions scholars address and why. Through primary and secondary sources, we will explore issues of race, gender, religion, the family, the economy, politics, and the meaning of community. “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) Course Goals and Expectations: Upon completion, students should be able to: analyze significant political, socioeconomic, and cultural developments in colonial American history draw conclusions and form opinions based on a critical analysis of historical facts and evidence (both primary and secondary) and effectively communicate those conclusions and opinions both orally and in writing analyze the similarities among and differences between the various colonies—and what led to and the consequences of those similarities and differences Evaluate the various geographical, cultural, political and economic factors that have affected the evolution of the American colonies. understand the role that race, class, gender, and ethnicity played in early American cities, towns, villages, and communities analyze contemporary events and organizations from an historical perspective. develop both a curiosity about history and the intellectual tools for a lifetime of study 2 All work turned in for this course must be completed on your own without unauthorized assistance. I do send cases of plagiarism to the Judicial Review Board! See below for a MUCH longer discussion of plagiarism. Required Readings: Anderson, Virginia DeJohn, Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America Bonomi, Patricia U., Lord Cornbury Scandal: The Politics of Reputation in British America Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity Lepore, Jill. New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan Taylor, Alan, American Colonies: The Settling of North America Wulf, Karin. Not all Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia Grading: The following breakdown is a general guideline to how I assign grades. A -- superlative, an outstanding grasp of facts, using them in support of an equally strong evaluation. B -- strong, with notable strengths balanced by some weaknesses in either evidence or evaluation. NOTE THAT GETTING A B OF ANY STRIPE MEANS YOU ARE ABOVE AVERAGE AND IT DOES NOT MEAN YOU ARE A FAILURE!! C -- adequate, on target, but with a limited grasp of either the evidence or evaluation, leaving the work narrow, unclear, and/or uneven. D -- problematic, often with factual errors and little evaluation, but with some points on target. F -- unacceptable, substantial misunderstanding of evidence and its context. LETTER GRADE A AB+ B BC+ C CD+ D DF HONOR POINTS 4.0 3.7 3.3 3.0 2.7 2.3 2.0 1.7 1.3 1.0 0.7 0.0 NUMERIC GRADE 92-100 90-91 88-89 81-87 79-80 77-78 69-76 67-68 65-66 55-64 50-54 <50 3 In calculating your final grade, the requirements will be weighed as follows (detailed descriptions follow): Attendance Participation New France OR Colonial Maps Written Analysis See the descriptions of the assignments at the end of the syllabus One-page reflection papers Colonial House Analysis Research paper 5% 15% 15% 10% 25% 30% In compliance with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act, reasonable accommodation will be provided to students with documented disabilities on a case-by-case basis. Students must register with Student Disability Services and provide appropriate documentation to the College before any academic adjustment will be provided. Attendance and Participation You will get TWO “free” absences (one week of classes). After that I will deduct one letter grade for each day you are absent (that is, your grade with start with an A, then drop to an A- for the first absence after the two free absences, then to a B+ for the next absence, and so on). After that, you must have an official written excused absence for the absence to be considered legitimate. DO NOT attempt to put me in the position of trying to decide which absences sound legitimate and which do not. Either save your absences for illness or plan your two days off wisely!!! This is Ithaca College’s official policy about visits to the Health Center: The IC Health Center no longer routinely issues "blue notes" documenting students' visits. According to recent policy, “We believe that students have the same responsibility for understanding and meeting the attendance requirements of their faculty as do employees in the workplace. Neither faculty nor students should be misled into overvaluing a ‘doctor's note.’ When necessary we will continue to provide students with written documentation for severe, prolonged, or unusual illness that causes them to miss class, e.g. in uncommon circumstances like those that might require any of us to provide a medical note to our employer. We will ask that these visits be by appointment, as they would be in the community, and will seek permission to document pertinent medical details when required.” This is Ithaca College’s Official Attendance policy: “Students at Ithaca College are expected to attend all classes, and they are responsible for work missed during any absence from class. At the beginning of each semester, instructors must provide the students in their courses with written guidelines regarding possible grading penalties for failure to attend class. Students should notify their instructors as soon as possible of any anticipated absences. Written documentation that indicates the reason for being absent may be 4 required. These guidelines may vary from course to course but are subject to the following restrictions: • In accordance with New York State law, students who miss class due to their religious beliefs shall be excused from class or examinations on that day. Such students must notify their course instructors at least one week before any anticipated absence so that proper arrangements may be made to make up any missed work or examination without penalty. • Any student who misses class due to a verifiable family or individual health emergency, or to a required appearance in a court of law shall be excused. The student or a family member/legal guardian may report the absence to the Office of Student Affairs and Campus Life, which will notify the student's dean's office, as well as residential life if the student lives on campus. The dean's office will disseminate the information to the appropriate faculty. Follow-up by the student with his or her professors is imperative. Students may need to consider a leave of absence, medical leave of absence, selected course withdrawals, etc., if they have missed a significant portion of classwork.” **PLEASE NOTE: Class participation means not simply showing up for class discussions, rather it means actively participating in those discussions. There is a direct correlation between attendance and discussion—if you are not in class, you cannot obviously participate. I watch and take notes—especially when you are in groups so don’t think this is a time to let someone else do the work. If you truly believe you cannot talk in front of others, please see me immediately and I will work something out with you. I have LOTS of class discussion because I think it is important for you to be ACTIVE learners. You learn more and you learn it better when you become an agent of your own education. It also makes the class more fun and engaging for all of us. "Colonial House" This is a PBS video about "Over two dozen modern-day adventurers from the US and UK" who “find out the hard way what early American colonial life was really like when they struggles to create a functioning and profitable colony.” The 8-hour video tracks “the first hand experiences of the colonists as they live for five months on an isolated stretch of the Maine coast. What happens when people are removed from familiar modern conveniences and placed into a 1628-era society with puritanical civil laws, rigid class and gender roles, indentured servitude, and mandatory religious worship?” You will ”witness the colonists' personal and communal challenges, seeing both the expected—backbreaking labor, bad weather and primitive living conditions—as well as the unexpected--religious conflicts, surprising confessions, devastating news from the outside world, and even an AWOL colonist. Colonial House brings history to life and provides a glimpse into the daily life and experiences that helped shape our national character.” I will show episodes 1, 4, 6, 7, and 8 in class. You must see the other episodes outside of class (the scheduled viewing times and places are below). According to IC policy, I must hold class during the exam period (state law requires that we meet as a class a specified number of hours and IC has included the exam period in those required hours)—or I can require an equivalent amount of time outside of the class sometime during the semester. So not only do I want you to see the entire series, viewing two episodes of “Colonial House” outside of class fulfills that requirement and we will not have to meet during exam week. 5 Normally I teach this course on a TR schedule, but this semester I have switched to a MWF schedule. The reason you need to know that is that it will be difficult for me to get an episode of “Colonial House” in one class period since most are slightly longer than 50 minutes. That means on those days, I will start the documentary right on time (if not a minute or two early) and will go the entire class period (if not a minute or two longer). Believe me, on those days I have to cut it a few minutes short, you will be disappointed. At the end of the semester, you will write an analysis of the video using ALL the readings in the class. By this point, you will be quite knowledgeable about colonial American history and this is your chance to reflect upon the material and present your culminating thoughts. Since “Colonial House” only portrays late seventeenth century New England from a particular perspective, you must -compare and contrast it with life in other colonies -compare and contrast it with what you learned about life in New England (that is, was it historically accurate?) -explore how AND WHY life changed over time (if it did) You should, of course, discuss issues of race, class, gender, politics, culture, and social conditions. Hopefully you will come to understand and appreciate the complexity of early America! A paper that merely discusses “Colonial House” and that does not address the above issues will not succeed. You must integrate the semester’s readings with the documentary. Weekly reflection papers FOR EACH READING ASSIGNMENT beginning the week of September 25 (that is, this requirement does not apply to Taylor’s American Colonies), you must write a one page (and no more than one page) reflection paper and it must be completed by the date of the reading assignment. I will not collect them regularly, but you better have them done in case I do or in case I call on you to talk about what you wrote. Here are some issues you could address—don’t focus on the same issue for every reaction paper, however. the author’s main argument (that is, the thesis) the main points the author uses to prove that argument is the author convincing and why or why not? analyze the sources the author uses as best you can what do you think is the most important point or points you learned from the reading (this is not necessarily the same as the author’s main points) and explain why this seems important to you 6 what connections does this reading make to earlier readings? Start analyzing patterns— stepping back and drawing broad implications for your understanding of early America I will not grade these individually, but I will read them and I take very seriously the simple fact of you doing them regularly and consistently. Your grade for this part of the course will depend heavily on whether you are doing the work or not. Research Paper This paper is to be at least 15 pages long on any topic related to colonial America (just a gentle reminder that for the purposes of this class, the colonial period ends in 1763). Think about what interests you. If you don’t pick a topic you like, it will be a VERY long semester. If you get stuck, you should look through the table of contents and index of Alan Taylor's American Colonies: The Settling of North America. I also have a 5-volume encyclopedia of colonial history in my office that you are welcome to come in and look through. Between the two you should get a good sense of the wide variety of topics you could pursue. Of course, I encourage you to see me in my office to talk about your topic. At any rate, this paper should not be simply a retelling of other historians’ work. You MUST base your research as much as possible on primary sources. Your final product should involve historiography, critical analysis, evaluation, and selection of primary and secondary source materials—and you should weave all of this into a clear and logical narrative. There are sufficient printed sources between IC and CU—and there primary sources on the Internet. I also have several different primary sources that you are welcome to use. Speaking of the internet, you absolutely CANNOT use it for secondary sources and I must approve what primary documents you use. If I see any reference to Wikipedia, I will lower your grade. ALL PAPERS ARE TO BE TYPED (12 POINT FONT, DOUBLE SPACED WITH 1” MARGINS ALL AROUND. PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING DATES: A one-page research prospectus that describes the topic, takes a thoughtful look at initial assumptions, details research questions, and list at least two secondary sources and two primary sources (court records, newspapers, letters, diaries, visual images, artifacts, the built environment--houses, gravestones) is due on Friday, September 28. This means, of course, that you cannot put this off to the last minute. It requires you to think about your project and to explore whether you can do what you want to do. A preliminary bibliography is due on Friday, October 10. A historiographical analysis (which will become part of your final version) is due on Friday, October 24, a revised bibliography and your introduction (which will become part of your final version) are due on Friday, November 7. I am giving you the option of turning in a rough draft which is due Friday, November 14. IF YOU DON’T TURN IT IN ON THAT DAY, I WILL NOT READ YOUR ROUGH DRAFT NO MATTER HOW MUCH YOU BEG, PLEAD, CRY, OR SCREAM. The final paper is due on Friday, December 5. PAY ATTENTION: THESE DEADLINES ARE NOT OPTIONAL. Incomplete or missing assignments will be penalized five points for each infraction (think about it—if you had an 85 (that is, a B) on the final paper 7 and incurred one 5-point penalty along the way, you would get an 80 (that is, a B-). NOW THE NITTY-GRITTY RULES. They are designed to create a professional intellectual atmosphere in which we treat each other with respect and so there are no distractions or disruptions for the 75 minutes that I consider “mine.” JUST A WORD OF WARNING, I AM VERY SERIOUS ABOUT THEM. I DO NOT GIVE EXTENSIONS, I DO NOT ACCEPT LATE ASSIGNMENTS—so read the syllabus carefully and plan your semester accordingly. You CANNOT have a cell phone turned on during class—not even on vibrate mode. You CANNOT have your cell phone out and on the desk—that is, you CANNOT use it to check the time or to check or send text messages. If I catch you using your phone during class, I will ask you to leave the room and I will not give you credit for attending class that day. If you use a computer to read course material or take notes, you cannot use it to check email, Facebook, Twitter, or the internet. If I ask, you must be able to show me that you are only using your computer for this class and this class only. If you find the class so boring that you simply must use your computer in inappropriate ways, then I suggest you drop the course. It is distracting to me and to your fellow classmates. Do not walk in and out of class at your leisure. It is rude and disruptive--not only to me but especially to your fellow students. If you do, I will deduct one point from your total attendance points for each time you do. If you leave 10 minutes early or arrive more than 5 minutes late, I will NOT credit you with attending class. In addition, if you walk in after I have begun to take roll, it is your responsibility to make sure I have marked your attendance. Don’t leave class without making sure. If you drop me an e-mail several days or several weeks later and say, by the way . . . there is likely no way I can verify the veracity of your claim. If you miss a class, it is your responsibility to follow up to see if I made any announcements, provided any handouts, or handed back assignments AVOIDING PLAGIARISM Every college takes plagiarism very seriously and provides penalties for those who are caught practicing it. For the purposes of college writing, we may define "plagiarism" as "the use of someone else's published or unpublished material or ideas without proper citation." These rules apply to both rough drafts and final versions. Plagiarism can take many forms; the worst cases involve obvious attempts at cheating. A handout distributed by the IC Writing Center lists these common forms of plagiarism: 1. Handing in a paper written by someone else as if it were your own. 2. Plagiarizing your own work by handing in a paper written for another course (unless both instructors know about this and agree to it). 3. Copying directly from sources without using quotation marks; cobbling together whole papers from bits and pieces drawn from several published sources. 8 More often, though, student writers seem to lapse into plagiarism unintentionally by: 4. Failing to document borrowed words and ideas both in the body of the paper and in the Bibliography (historians follow the Chicago Manual of Style and we do NOT use a “works cited” page); just because something appears in your bibliography, it does not mean you can borrow from it freely and without acknowledgement. 5. Inadequately paraphrasing a source by only changing the original wording slightly, instead of rephrasing it in your own words. This may be the most common form of plagiarism. Borrowed quotations, information and ideas must be identified as such and properly documented. Actual quotations must be enclosed in quotation marks and provided with citations. If you summarize or paraphrase borrowed ideas and information in your own words, you don't need the quotation marks, but you still need to provide citations that tell where you got that information. To avoid plagiarism, you must know when to document the sources for your work and the correct procedures for doing so. What kinds of borrowings do you need to cite? This is one of the most vexing questions for student writers. A paper that consists almost solely of cited material may seem to lack original thought from its writer. But your thesis is only as strong as the evidence you use to support it, and in college papers, that evidence comes mostly from published sources. It may be easier for you to decide when you need to cite your sources if you keep in mind why you document your borrowings. You provide documentation of your sources for three reasons: 1. To acknowledge your borrowings from others; it's simply dishonest to do otherwise. 2. To lend credibility and authority to your claims. 3. To allow readers to refer back to your sources. The following is from the IC library—there is more information on their home page, so check it out! A definition from the Ithaca College Policies Manual 7.1.5.1 Plagiarism Whether intended or not, plagiarism is a serious offense against academic honesty. Under any circumstances, it is deceitful to represent as one's own work, writing or ideas that belong to another person. Students should be aware of how this offense is defined. Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of someone else's published or unpublished ideas, whether this use consists of directly quoted material or paraphrased ideas. Although various disciplines follow styles of documentation that differ in some details, all forms of documentation make the following demands: That each quotation or paraphrase be acknowledged with a footnote or in-text citation; 9 That direct quotations be enclosed in quotation marks and be absolutely faithful to the wording of the source; That paraphrased ideas be stated in language entirely different from the language of the source; That a sequence of ideas identical to that of a source be attributed to that source; That sources of reprinted charts or graphs be cited in the text; That all the sources the writer has drawn from in paraphrase or direct quotation or a combination of paraphrase and quotation be listed at the end of the paper under "Bibliography," "References," or "Works Cited," whichever heading the particular style of documentation requires. A student is guilty of plagiarism if the student fails, intentionally or not, to follow any of these standard requirements of documentation. In a collaborative project, all students in a group may be held responsible for academic misconduct if they engage in plagiarism or are aware of plagiarism by others in their group and fail to report it. Students who participate in a collaborative project in which plagiarism has occurred will not be held accountable if they were not knowledgeable of the plagiarism. What, then, do students not have to document? They need not cite their own ideas, or references to their own experiences, or information that falls in the category of uncontroversial common knowledge (what a person reasonably well-informed about a subject might be expected to know). They should acknowledge anything else. Paraphrasing How to Recognize Unacceptable and Acceptable Paraphrases. (taken from Plagiarism: What it Is and How to Avoid It). Retrieved October 29, 2001 from the Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. http://www.indiana.edu/~wts/wts/plagiarism.html An acceptable paraphrase avoids plagarism when the writer: accurately relays the information in the original. uses her or his own words. lets her reader know the source of her information. Common Knowledge 10 You do not have to quote or cite a fact that either is documented in numerous places or widely known. It is common knowledge, even if you didn't know it before, that Abraham Lincoln was our 16th President. It may not be widely known that Jesse Jackson was born on October 8, 1941, but that information can be looked up in any of multiple encyclopedias and biographical dictionaries. Therefore you do not need to document either of these facts. What is not common knowledge are facts that may be difficult to document or ideas that are more interpretation than fact. Right-wing pundit Ann Coulter has lied about her age, according to left-wing pundit Al Franken. If different sources supply different birthdates for her or if her birthdate is not easily found, you may need to cite the source if you are going to include her birthdate in your paper. If this were a formal paper, the "fact" reported by Al Franken would need to be documented more precisely. Avoiding Plagiarism also adapted from Plagiarism: What it Is and How to Avoid It). Retrieved October 29, 2001 from the Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. http://www.indiana.edu/~wts/wts/plagiarism.html 1. If you have copied it directly, put it in quotations 2. When taking notes, make sure you mark what is copied directly and what is not. 3. When you paraphrase, you must use your own words. Do not just rearrange or replace a few words. 4. Since accidents can happen, check your quotations to be sure they are accurate and double check your paraphrases to be sure you have not repeated lengthy phrases or significant words found in the original text. THIS IS FROM THE STUDENT CONDUCT CODE OF ITHACA COLLEGE: Whether intended or not, plagiarism is a serious offense against academic honesty. Under any circumstances, it is deceitful to represent as one's own work writing or ideas that belong to another person. Students should be aware how this offense is defined: Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of someone else's published or unpublished ideas, whether this use consists of directly quoted material or paraphrased ideas. Although various disciplines follow styles of documentation that differ in some details, all forms of documentation make the following demands: That each quotation or paraphrase be acknowledged with footnotes or in-text citation; That direct quotations be enclosed in quotation marks and be absolutely faithful to the wording of the source; 11 That paraphrased ideas be stated in language entirely different from the language of the source; That a sequence of ideas identical to that of a source be attributed to that source; That all the sources the writer has drawn from in paraphrase or direct quotation or a combination of paraphrase and quotation be listed at the end of the paper under "Bibliography," "References," or "Works Cited," whichever heading the particular style of documentation requires. A student is guilty of plagiarism if he/she fails, intentionally or not, to follow any of these standard requirements of documentation. In a collaborative project, all students in the group may be held accountable for academic misconduct if they engage in plagiarism or are aware of plagiarism by others in their group and fail to report it. Students who participate in a collaborative project in which plagiarism has occurred will not be held accountable if they were not knowledgeable of the plagiarism. What, then, do students not have to document? They need not cite their own ideas, references to their own experiences, or information that falls in the category of uncontroversial common knowledge (what a person reasonably well-informed about a subject might be expected to know.) They should acknowledge anything else. Note: Students who would like additional help in learning how to paraphrase or document sources properly should also go to the Writing Center. I THINK YOU GET THE PICTURE! 12 TOPICS, READINGS, AND ASSIGNMENTS Aug 27 Aug 29 Brief introduction to course "Colonial House" Episode 1 THE BROAD OVERVIEW Sept 1 Sept 3 Sept 5 LABOR DAY—NO CLASS! Taylor, American Colonies, “Introduction” and Part I, “Encounters,” Chapters 1-3 Taylor, American Colonies, Part I, “Encounters,” Chapters 4-5 Sept 8 Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Colonies,” Chapters 6-8 EVENING SHOWING of “Colonial House,” episode 2, 7:00 p.m Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Colonies,” Chapters 9-10 Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Colonies,” Chapters 11-12 Sept 10 Sept 12 Sept 15 Sept 17 Sept 19 Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Empires,” Chapters 13-14 EVENING SHOWING of “Colonial House,” episode 3, 7:00 p.m. Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Empires,” 15-16 Taylor, American Colonies, Part II, “Empires,” Chapters 17-18 (to page 437— stop at “Imperial Crisis”) THE UNIQUE FOCUS Sept 22 Sept 24 Sept 26 Sept 29 Oct 1 Oct 3 Oct 6 Oct 8 Oct 10 Marcy Norton, “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 3 (June 2006), 660-691. POSTED ON SAKAI EVENING SHOWING of “Black Robe”—no regular class Natalie Zemon Davis, “New Worlds: Maria L’Incarnation,” in Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives. POSTED ON SAKAI (You must read this BEFORE you come to the film this evening) Mary Beth Norton, “Gender and Defamation in Seventeenth-Century Maryland,” William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), 3-39. POSTED ON SAKAI DUE: Research prospectus (see description above) The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, “What’s in a Name,” Prologue, and Chapters 1-2 The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, 3-5 The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, Chapters 6-8 and Epilogue Anderson, Creatures of Empire, Prologue and Chapters 1-3 Anderson, Creatures of Empire, Prologue and Chapters 4-5 Anderson, Creatures of Empire, Chapters 6-7 and Epilogue DUE: Preliminary bibliography 13 Oct 13 Oct 15 Oct 18 “Colonial House” Episode 4 DUE: “Black Robe and Maria L’Incarnation Analysis FALL BREAK—NO CLASS! Oct 20 Oct 22 Oct 24 Bonomi, Lord Cornbury Scandal, Prologue and Chapters 1-3 Bonomi, Lord Cornbury Scandal, Prologue and Chapters 4-6 Bonomi, Lord Cornbury Scandal, Chapters 7-9 DUE: Historiographical analysis Oct 27 Essays from Martin Bruckner, ed., Early American Cartographies ON COURSE RESERVE: Jess Edwards, “A Compass to Steer by: John Locker, Carolina, and the Politics of Restoration Geography,” 93-115. Gavin Hollis, “The Wrong Side of the Map? The Cartographic Encounters of John Lederer,” 145-168 Essays from Martin Bruckner, ed., Early American Cartographies ON COURSE RESERVE: Matthew H. Edney, “Competition over Land, Competition over Empire: Public Discourse and Printed Maps of the Kennebec River,” 276-305 Judith Ridner, “Building Urban Spaces for the Interior: Thomas Penn and the Colonization of Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania,” 306-338 Oct 29 Oct 31 Pritchard, Margaret Beck, “Degrees of Latitude,” Colonial Williamsburg: The Journal of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Summer 2002. POSTED ON SAKAI Nov 3 New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, Prologue and Chapters 1-3 New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, Prologue and Chapters 4-5 New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, Chapters 6-7 and Epilogue DUE: Revised bibliography and your introduction Nov 5 Nov 7 Nov 10 Nov 12 Nov 14 “Colonial House,” episode 5 DUE: Map assignment Frank Lambert, "Pedlar in Divinity": George Whitefield and the Great Awakening, 1737-1745,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 77, No. 3 (Dec., 1990), 812-837. POSTED ON SAKAI David Hancock, “Commerce and Conversation in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic: The Invention of Madeira Wine,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Autumn, 1998), 197-219. POSTED ON SAKAI DUE: Optional rough draft—this is due in class and it must be a full rough draft 14 Nov 17 Nov 19 Nov 21 “Colonial House,” Episode 6 Wulf, Karin, Not All Wives, “Introduction,” and Chapters 1-2 Wulf, Karin, Not All Wives, Chapters 3-4 Nov 24 Nov 26 Nov 28 THANKSGIVING BREAK—NO CLASSES!! THANKSGIVING BREAK—NO CLASSES!! THANKSGIVING BREAK—NO CLASSES!! Dec 1 Dec 3 Dec 5 Colonial House" Episodes 7 Colonial House" Episodes 8 DUE: Research Paper—I will accept this paper until 5:00 p.m. Dec 8 Dec 10 Wulf, Karin, Not All Wives, Chapters 5-6 T. H. Breen, “An Empire of Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690-1776,” Journal of British Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4, Re-Viewing the Eighteenth Century (Oct., 1986), 467-499. POSTED ON SAKAI END OF SEMESTER CELEBRATION Dec 12 THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18—DUE NO LATER THAN 10:30 AM: Historical analysis of "Colonial House” (assignment description above). OF COURSE, I WILL GLADLY ACCEPT PAPERS EARLIER THAN DECEMBER 18. 15 ANALYZING NEW FRANCE Analyze the role of gender, race, cultural values, economic values, and/or religion (you do not have to incorporate all issues—the paper is too short for that—but you should explore at least three issues) in seventeenth-century New France using the book chapter “New Worlds: Marie De l’Incarnation,” the film “Black Robe,” Alan Taylor’s American Colonies, AND AT LEAST FOUR DOCUMENTS FROM THE JESUIT RELATIONS. You can find the entire collection online at http://puffin.creighton.edu/jesuit/relations. This database is fully searchable and how you choose to utilize the writings is up to you. For example, you could search for terms that seem relevant to you; you could search for Marie de l’Incarnation’s presence in the documents (either written by her or about her); you could search for particular years; or you could . . . . You might want to explore if and if so, how and why the role of gender, race, cultural values, economic values, and religion may have changed over the brief period of time the film and the chapter cover (you might want the documents you chose to go beyond that time frame to explore change over time more fully). If you so choose, you could also use the Norton article on gender and defamation to do some comparative analysis. At any rate, you should have a clear argument to make about New France and I MUST see evidence that you used the above sources. This paper should be 3-5 pages long. ANALYZING COLONIAL AMERICA THROUGH MAPS Analyze at least four early American maps (remember—only up to 1763) ACROSS TIME. You can either look at one area (New England, the Middles Colonies, the Chesapeake, the South, or the Caribbean) or compare areas (pick only two). Look closely at the details (zoom in!): images, names of places and things, boundaries, date of the maps, the map maker, who bought or owned the maps (yes, I know that you might not be able to locate some of the latter information). Then explain what these maps tell you about early American social, cultural, economic, or economic values. You should have a clear argument to make about maps. This paper should be 3-5 pages long. In addition to the five chapters/articles you read (make good use of them), be sure to return to Creatures of Empire and re-read what Anderson wrote about reading early maps (look at the footnotes for this section). It will be very helpful! Also, there are plenty of articles in Bruckner’s Early American Cartographies for further reference. I only assigned you four chapters from a total of twelve chapters. You will likely find the introduction very useful. I have put these two books on reserve to help you: Pritchard, Margaret, Degrees of Latitude: Mapping Colonial America Bruckner, Martin, The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity (chapter 1) 16 You could search for the specific maps in the assigned readings—especially if some seem like they would be particularly interesting or useful (DO NOT USE ONLY THE MAPS IN THE READINGS), but to make your life easier, I have listed here some internet sites for finding early American maps (there are certainly other sites and I URGE you to use them): http://www.history.org/history/museums/mappingExhibit.html http://www.davidrumsey.com/ http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/maps/ (in the drop-down box navigate to North America) http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/themes/colonial-america/exhibitions.html http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/maps/maps.cfm