Addendum to the Institutional Report 9-21-12

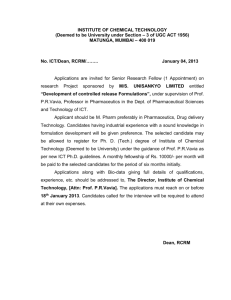

advertisement

1 Addendum to the NCATE Institutional Report Submitted by the University of Cincinnati BOE Visit: November 4-6, 2012 Responses to Concerns and Requests for Further Evidence Please refer to www.uc.edu/cech-accreditation for the NCATE Institutional Report, evidence, and further documentation. 2 In this addendum we have generated a response to each of the areas of concern and question posed in the NCATE Offsite Report to the University of Cincinnati. In addition, we have a parallel document that includes the evidence requested. Though it was our intent to provide the evidence directly with the narrative for ease of review, a separate document had to be generated due to page limitations in uploading through the aims.ncate.org site. We have, though, wherever it is possible, placed the evidence directly in the narrative for the convenience of the reviewer. The heading for each narrative is the question from the report. Lengthy evidence will be available to each BOE team member on a jump drive. *Please direct any further questions or concerns to Annie Bauer (anne.bauer@uc.edu) and every effort will be made to respond within 24 hours. Conceptual Framework Concern: Evidence of a shared vision regarding the CF is a central goal. Evidence of a shared vision is documented in printed materials on every syllabus, in field and program handbooks, and in materials distributed by programs. During orientation candidates are provided information on the conceptual framework, and mentors/cooperating teachers share are evaluated on their consistency with the vision by university supervisors and candidates. Placements and mentors/cooperating teachers who do not share the vision are no longer used. In the last set of data related to evaluation of placements, candidates (N=391) rated consistency with philosophy and framework of the field and clinical placements with University of Cincinnati programs at a mean of 4.14, with 1 being strongly disagree ranging to 5 strongly agree, with 174 candidates choosing 5 strongly agree. University supervisors (N =271) rated the item at a mean of 4.29 with 150 selecting 5 strongly agree. Consistency in the framework appears beyond recognizing the words to the practice of field and clinical faculty in the schools. 1. Who was involved in the development of the CF? There has been long standing participation of the professional community in the development, review, and revision of the conceptual framework. Beginning in 1986-1987, members of the professional community – particularly teachers in the Cincinnati Public Schools partner schools were engaged in the development of the Pattern Language. As those efforts moved to the Continuous Improvement Committee and eventually the University Council for Educator Preparation, members of the community have been an active part in the development, implementation, and revision of the conceptual framework. That involvement is documented by the following chronology (further evidence is also available in the addendum to Standard 6, summary and minutes of the University Council for Educator Preparation): 1987 – Teacher preparation programs initiated redesign; knowledge base described as “A Pattern Language for Teaching” grounded in Alexander’s pattern language for architecture and design. Consistent with Alexander’s description of patterns the conceptual framework began to evolve; “patterns can never be ‘designed’ or ‘built’ in one fell swoop- but patient piecemeal growth, designed in such a way that every individual act is always helping to create or generate these larger global. 1993 – “A Pattern Language for Teaching” became NCATE approved conceptual framework and knowledge base, with continued support from faculty members in the Cincinnati Public School Professional Practice Schools 3 1997 – “A Pattern Language for Teaching,” in its third iteration, is named as conceptual framework for the unit’s initial licensure programs; Educational Administration, Counseling, School Psychology, and Literacy posit individual conceptual frameworks grounded in their various programs. Public school teachers continue to review the document and participate in its development. 2000 – Programs are charged by Dean Lawrence Johnson to review their programs in terms of content area knowledge, resources, and national standards. Spring, 2001 – Continuous Improvement Committee formed to begin to address accreditation needs. Members include representatives of each educator preparation program and the public schools. Faculty surveyed related to program goals and candidate dispositions, mentor teachers, and principals responded to a survey asking for feedback on components from various sources (InTASC, state standards, literature review) June, 2001 – Continuous Improvement Committee formulates dispositions and indicators of conceptual framework. Members of these work groups include teachers from Cincinnati Public Schools. September, 2001 – Evolving document of Conceptual Framework provided to Workgroup Chairs and Program Chairs for discussion and faculty comments. School faculty were provided drafts to share with their colleagues. September, 2001 – Evolving document of Conceptual Framework posted for faculty and community comment on Blackboard site (guest accounts for mentor teachers negotiated) October, 2001 – Continuous Improvement Committee endorses conceptual framework and theme phrase. October, 2001 – Programs requested to comment and endorse framework. October, 2001 – December, 2001 – Individual programs endorse framework. December, 2001 – Edited Conceptual Framework posted and distributed for final review; summaries distributed to faculty members in the Professional Practice Schools and to mentors/cooperating teachers. January, 2002 - Begin to infuse conceptual framework statements into materials; Conceptual framework distributed via Blackboard and hard copy to mentors, candidates, faculty members July, 2002 – Conceptual framework presented to freshmen in teacher education programs during freshmen orientation. Autumn, 2002 – Conceptual framework reviewed with members of the University Council for Educator Preparation. Conceptual framework included in Handbooks for Professional Experiences provided to candidates and mentors. January, 2003 – Conceptual framework distributed to all faculty members in the unit and representatives of the professional community for review. April, 2003 – Conceptual framework discussed with Advisory Group members. May, 2003 – Conceptual framework reviewed and revised; Retreat for Teacher Education Faculty to discuss infusion of Conceptual Framework throughout programs Academic Year, 2003-2004 – Conceptual framework infused through practice and programs; focus on getting and maintaining involvement from members of the community May, 2004 – Development of briefings of dispositions and conceptual framework generated by UCEP to share with community November, 2004 – NCATE onsite visit; Institutional report grounded in conceptual framework May 2006 – Conceptual framework placed on UCEP agenda for 2006-2007 revision 4 May 2007 – Conceptual framework revision begun with UCEP meeting and members charge to discuss with programs or colleagues; updated through updating language and knowledge base, programs reaffirm endorsements Summer 2009 – University of Cincinnati responded to invitation to become a Transformation Initiative institution. Academic Year 2009-2010 – University Council for Educator Preparation begins discussion of Transformation Initiative; began shift of context to high needs schools and monitoring use of high needs schools as placements Summer 2010 – Stone Soup Group (university and school faculty engaged in action research in high needs schools) becomes the “summer institute group” taking the lead in developing the Transformation Initiative efforts November 2011 – Approval of conceptual framework revisions and assessment system revisions by UCEP February 2012 – UCEP discussion moving Transformation Initiative from narrative into themes grouped in three areas 2. How are faculty, both campus- based and clinical, prepared to implement the Transformation Initiative? “Preparation” seems to suggest that the Transformation Initiative was created and presented, and that participants in the process somehow needed to be made “ready.” Our initiative is more organic. The themes of the initiative were derived from the work of programs, individual faculty members, and our school partners. Through an evolving group of work groups, beginning with a “Stone Soup” group, morphing into the “Summer Institute” group, and becoming a steering committee engaged in increase the cohesive and developmental nature of our program around effective teaching of all students, the idea of “preparing” participants did not occur. Rather, the initiative came about by continuing to stretch the ideas within the themes and solidify our efforts into the three research questions. 3. How has the expanded definition of diversity been incorporated in Standard 4? The expanded definition of diversity has pushed us to begin to put the following statement on our syllabi and Blackboard communities: CEC believes diversity means understanding and valuing the characteristics and beliefs of those who demonstrate a wide range of characteristics. This includes ethnic and racial backgrounds, age, physical and cognitive abilities, family status, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religious and spiritual values, and geographic location. The University of Cincinnati embraces diversity and inclusion as core values that empower individuals to transform their lives and achieve their highest potential. This course offers a challenging, yet nurturing intellectual climate with a respect for the spectrum of diversity and a genuine understanding of its many components — including race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity and expression, age, socio-economic status, family structure, national origin, sexual orientation, disability and religion — that enrich us as a vibrant, public, urban research university. This course is energized by the spirit of pluralism — the quest to celebrate differences within an intellectually stimulating environment, to seek understanding across social, economic and cultural barriers, to pursue transformation through sustained interaction with others, and to empower all members of the University of Cincinnati community. You are invited to explore your own diversity! 5 In addition, the expanded definition has pushed us to develop a rubric to help our candidates understand writing “about other people’s children.” This is not related to being “politically correct” or inoffensive. In “Cultural conflict in the classroom” (1995) Delpit describes the challenges individuals face "to perceive those different from themselves except through their own culturally clouded vision" (p. xiv).Our candidates come to us with varied levels of experience in writing about people who do not look, live, think, or act like them. Blatant racism is rare, yet in writing candidates struggle to write about other people’s children, and need support in avoiding the “all they need to do” thinking of new teachers and the deficit thinking of their own school experience. In addition, they tend to be concerned about what Milner (2011) describes as the achievement gap, an after the fact measure of performance. Rather, Milner contends the emphasis should be on the opportunity gap, the differences in how we are teaching students, economic resources, curriculum rigor, and expectations. In attempting to devise a rubric to support their communication efforts, we began with the literature (primarily Delpit, Gay, Gorki, and Millner) and an assignment, reviewed candidates’ responses, and generated this rubric for discussion: https://uceducation.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_0GnANWnnGxXF1je 4. How has the institution implemented the TI proposal to meet the claim that the new focus is on the learning of the students of their candidates? An example of the ways in which this shift has on our work is the development of our assessments. For example, in planning, we typically used a lesson plan and rubric similar to many other programs. We now are teaching students an “analysis of student work” protocol which goes beyond planning what to teach. Rather, candidates collect a set of student work, analyze the performance related to the standard being taught, and generate future teaching plans. An example of the protocol used is the Analysis of Student Work provided in the Evidence Addendum page 3. 5. How did the transformation initiative emerge from the conceptual framework? a. In what ways is it a natural extension? b. Are there any emerging elements that “push” the conceptual framework forward? c. How might you expect the transformation initiative to influence the conceptual framework in the future? The Transformation Initiative emerged from these candidate performance expectations. Candidates of the University of Cincinnati are committed to transforming the lives of P-12 students, their schools, and their communities, and Demonstrating the moral imperative to teach all students and address the responsibility to teach all students with tenacity. Addressing issues of diversity with equity and using skills unique to culturally and individually responsive practice. Using assessment and research to inform their efforts and improve outcomes. Demonstrating pedagogical content knowledge, grounded in evidence-based practices, committed to improving the academic and social outcomes of students. The Transformation Initiative themes related to the “who” – our candidates are both related to and propel the performance expectations related to the responsibility and moral imperative to teach all children and developing skills related to culturally and individually responsive practice. To increase the likelihood that these performance expectations are met, we must begin by helping candidates come to term with unintentional barriers and bias. Without equity, our candidates may fall into a deficit/remediation way of thinking rather than celebrating the funds of knowledge of their students and building on that unique information. Our emphasis on preparing candidates to teach in city schools 6 and providing those experiences further pushes our performance standards to a particular and challenging context – urban, high needs schools. Emphasizing reflection and analysis of teaching effectiveness is related to using assessment and research to inform their research and demonstrating pedagogical content knowledge. We are committed to helping our candidates truly reflect, and have begun to use the phrase “analysis of teaching” to urge them toward more sophisticated reflections. Our emphasis on analysis is apparent in the reflection rubric developed (https://uceducation.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_a2Tc3ZbGCTllJRy ). In addition, the Collaborative Assessment Log pushes candidates to identify evidence-based practice and emphasize both academic and social outcomes. Transformation Initiative More specific data to review the status and implementation of each of the themes of the Transformation Initiative and the relationship of themes to standards. The TI timeline to effectively assess the status of TI implementation. The following table indicates status of each element and the anticipated timeline. Research Question 1: What is the impact of changes in program structures and emphases on candidate knowledge, skills, and dispositions? Action Planned Implement coursework and embedded field experiences in schools with p-12 teacher partners Adding more and earlier field experiences Addressing unintentional barriers and biases Preparing teachers for city schools Implementation of researchbased strategies Academic language development Reflection When? Fall 2011 Status? ECE pilots; SPED; Grades 7-12 English/LA Spring 2012 Fall 2012 MDL pilots Planned Summer 2012 – Fall 2013 Fall 2011 Work group aligning series of experience and assessments Data Comparison of performance of candidates on dispositions and goal setting to past groups Program evaluations, candidate performance Assessments, rubric for candidate written efforts, racial identity activities All candidates in >1 urban, high Tracking placements; scripts ; focused poverty placement by policy disposition assessment Fall 2011 Research based strategies Meta-analysis of ratings of use of required on all plans/units research-based strategies Spring 2012- Reviewing literature; initiating Specific strategies to work with Fall 2013 work on strategies candidates to be developed Fall 2012Reviewing literature; developing Rubric for depth of reflection to be Fall 2013 rubric; collaborating with school developed partners on CAL Research Question 2: Does the Teacher Performance Assessment generate evidence that is used in refining educator preparation efforts? Action Planned When? Status? Data Implementation of TPA for all Spring 2012 MDL, ECE, and SPED uploading Available October 2012 programs Summarization and analysis of Winter 2013 Planned Summarized March 2013 quantitative data Coding of written comments Spring 2013 Planned Summarized May 2013 7 Summarization / analysis to Fall 2013 Planned Presented August 2013 programs for review to improve candidate performance and program Social Validity Questionnaire – Winter 2014 Planned Surveys and interviews conducted by including p-12 partners March 2014 Generating publications Sum2014 Planned Submitted by September 2014 Research Questions 3: What is the impact of changes in program structures and emphases on the learning and behavior of p-12 students? Action Planned Implement funded Evaluation Mosaic Studies Reissue rfps for Mosaic Evaluation project; commissioning other studies Identification of assessments Review of data generated Revising assessments Reliability, bias, and consistency studies When? Fall 2012 Planned Status? Spring 2013 Data Spring 2012 Planned Summer 2013 Spring 2012 Spring 2013 Spring 2013 2013-2014 AY Planned Planned Planned Planned Piloted Fall 2012 Summarized Spring 2013 Completed by June 2013 Completed by June 2014 Institutionalize assessments to Fall 2014 Planned Fall 2014-Fall 2018 collect adequate data to identify trends Research Question 4: What assessments emerge to measure the development of candidate knowledge, skills, and dispositions prior to student teaching and the Teacher Performance Assessment? Action Planned When? Status? Data Identify signature embedded Fall 2012 Planned End of December 2012 assessments Post signature assessments and rubrics on program web-pages Spring 2013 Planned Completed? Implement Assessments Spring 2013 Planned End of spring 2013 Review data and redesign Fall 2013 Planned End of December 2013 Reliability, bias, and consistency 2013-2014 Planned Completed by June 2014 studies AY Institutionalize assessments to Fall 2014 Planned Fall 2014-Fall 2018 collect adequate data to identify trends Evidence of how and specifically where the recommendations of the NCATE Committee on Transformation have been taken into account. Clarify the version for this visit. The version of the Transformation Initiative to be used by the Board of Examiners is provided as a separate document. Though submitted in April, 2011, our initiative was not reviewed for over a year. With the offsite and onsite reviews approaching, we reflected on the proposal, simplified the language and resubmitted it. In late March, we were notified that the proposal was approved and provided a series of questions for consideration which we felt were excellent feedback. In response, we: a) Re-studied the work of Haberman, Diez, and Darling-Hammond, and supplemented the literature support for our work; 8 b) Expanded our theoretical perspective, realigning our effort with the conceptual framework and desired outcomes for our candidates; c) Reorganized our outcomes as goal statements, clarifying potential results so that we will be able to more clearly judge the success and impact of the proposal; d) Provided additional information related to the development of our signature assessments; and e) Clarified our research questions, data sources, and methodology. Standard 1 1. Alumni survey data regarding program effectiveness and satisfaction. At the University of Cincinnati, alumni survey data are referred to as “follow-up” survey data. Follow-up program completer surveys are one of multiple measures used to monitor candidate success. The follow-up survey provided in the evidence addendum demonstrate our continued effort to employ a simple, valid tool and to gather adequate returns that results are useful. The 2009 Follow-Up Survey (2007 and 2008 program completers – 38 responses) were mailed to graduates’ homes with an addressed, postage paid envelopes. The spread of responses across the programs did not generate strong data for programs. In the 2010 Follow –up Survey (2008 and 2009 completers – 42 responses) we received slightly more responses through the use of Surveymonkey. Our 2011 surveys (2009 and 2010 completers – 15 responses) had far fewer responses; we later learned that the University of Cincinnati had begun closing student email accounts after a year. In order to deal with this problem, we asked candidates to provide us with a “permanent” (as permanent as email addresses can be) email address on the licensure application form. This was successful in raising our response rates, and we were able to report initial and advanced programs separately. These 2012 surveys (2010 and 2011 completers) were also administrated through Qualtrics, which is more user friendly. “Alumni Survey Data” are provided in the Evidence Addendum beginning on page 5. 2. Assessments used for candidates within the Curriculum & Instruction M.S.Ed. program. It is not clear in Exhibit 1.4.e.6 how candidates meet each of the NBPTS standards. The Curriculum and Instruction M. Ed. program is grounded in the six propositions of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. These principles form a framework for “the rich amalgam of knowledge, skills, dispositions, and beliefs” that characterize effective teachers. These are not standards and are not something that is “met.” Each of the 25 NBPTS certificates has a unique set of standards and are grouped in three areas: Preparing the way for productive student learning; Advancing student learning in the classroom; and supporting student learning through long-range initiatives. A single certificate may have 15-20 standards related to both the content area and the age of the students involved. Our advanced students in Curriculum and Instruction represent teachers in a variety of content areas and age groups, and to use the individual standards of each of the 25 certificates may generate several “cohorts” of one candidate. Rather than using these standards, we aligned the program with the propositions or framework of the NBPTS effort. Direct alignment, however, is with our institutional standards. Our institutional standards are assessed at the M. Ed. level through performance in coursework, dispositions demonstrated, performance in action research (field experience), and written products. As we redesigned our programs in accordance with the NCATE 2008 revisions, we generated this table: 9 NCATE Language Institutional Standard Performance Assessments 1a. Content Knowledge for Teacher Candidates Candidates in advanced programs for teachers have an in-depth knowledge of the content that they teach. 1b. Pedagogical Content Knowledge and Skills for Teacher Candidates Candidates in advanced programs for teachers understand the relationship between content and content specific pedagogy. They are able to select and use a broad range of instructional strategies that promote student learning. 1c. Professional and Pedagogical Knowledge and Skills for Teacher Candidates Candidates in advanced programs for teachers synthesize research and policies that impact their work. 1d. Student Learning for Teacher Candidates Candidates in advanced programs for teachers understand and apply the major concepts and theories related to assessing student learning. 1g. Professional Dispositions for All Candidates Experienced teachers in graduate programs build upon and extend their knowledge and experiences to improve their own teaching and student learning in classrooms. Demonstrating foundation knowledge, including knowledge of how each individual learns and develops within a unique developmental context; Articulating the central concepts, tools of inquiry, and the structures of their discipline Demonstrating pedagogical content knowledge, grounded in evidence-based practices, committed to improving the academic and social outcomes of students. Grades in core coursework; Literature review Using assessment and research to inform their efforts and improve outcomes. Literature review; analysis of critical incident; cultural autobiography; Use of technology assessment Using assessment and research to inform their efforts and improve outcomes. Action research project; educator impact rubric Demonstrating the moral imperative to teach all students and address the responsibility to teach all students with tenacity; Addresses issues of diversity with equity and using skills unique to culturally and individually responsive practice. Dispositions assessment; Reflection and analysis of practice embedded signature assessment; Writing about other people’s children embedded signature assessment Action research project; Analysis of critical incident Candidates in these graduate programs develop the ability to apply research and research methods. They also develop knowledge of learning, the social and cultural context in which learning takes place, and practices that support learning in their professional roles. Confirm Praxis II pass rate as reported for consistency. Evidence was reviewed to insure that appropriate pass rates were documented. Involvement of the advanced programs in the Transformation Initiative. At this time the advanced programs are not engaged in the Transformation Initiative. The steering committee will review the potential of expansion of the Transformation Initiative across all programs. Standard 2 Policies for handling student complaints Students at the University of Cincinnati has several ways to address their complaints. These include addressing complaints made (a) at the college; (b) to the ombudsman; (c) through www.feedback.uc.edu ; and (d) through the student grievance procedures. Complaints made at the college. At every first year student orientation, the associate dean for academic affairs informs that concerns and issues that emerge should be dealt with the faculty member 10 first, and then addressed to the coordinator, school director, and finally the dean’s office. However, candidates frequently begin the process by going directly to the dean, associate dean, provost, or president. All complaints directed at the university level are returned to the dean’s office. The process followed by the associate dean is: 1. Student makes complaint to the dean, associate dean, provost, or president. 2. Complaint is forwarded to the associate dean for academic affairs. 3. The associate dean meets individually with the student to clarify the complaint. 4. The associate dean engages in fact finding, and in some cases is able to develop a solution after information is gathered. 5. If the complaint is not solved to the students’ satisfaction following information gathering, the associate dean meets with the coordinator to develop a plan. 6. If the student wishes, he or she meets collaboratively with the program coordinator and associate dean to develop a plan. If the student does not wish to meet but wants to continue the complaint, the associate dean serves as mediator between the two parties. 7. A solution is proposed and agreed upon (if possible). If a solution cannot be developed, the rationale for the solution is provided to the student. These cases usually involve the student’s request to be inconsistent with university or college policy. A summary of complaints that were addressed in this way for the 2011-2012 academic year follows: 2011-2012 Complaints file 11 12 sent to AB Aug 22 2012 Start Student Grad/UG Program Issue Resolution 8/8/11 a UG MDL b GRAD SPED struggling student; action plans; mother upset student needs help with drop/add 8/15/11 c UG SEC student removed from program; struggles in field plans developed; student unable to meet GPA requirements for cohort student registered for same class twice; staff helped documentation of performance in the field by several assessor shared with students 8/8/11 10/16/11 d UG SEC student has dispositional concerns meeting held with associate Dean student met w/RS; expressed strong statements about SEC program student concerned w/grade student agreed to work out problem with instructor instructor worked something out w/student student using wrong email 12/8/11 12/14/11 10/18/11 e GRAD SPED 10/28/11 r GRAD A & S/FL 10/29/11 g GRAD SPED 11/23/11 h UG ECE? 12/2/11 i GRAD SEC 1/3/12 j UG MDL 3/2/12 k UG ECE 3/7/12 3/22/12 l m UG GRAD SEC CI (MECI) 4/11/12 n GRAD CI student wondered why no one was responding to his emails student wanted specifics on program of study student having trouble connecting with instructor student ranting on social media; other students afraid student wondered about staying in licensure program student concerned about cohort process for MDL student struggling in field; parents involved student needed help with grade change grade problem reported by student student wanted to walk during created plan of study instructor using old work email Asst. Dean Student Services Center met with student; helped student understand Prog coord encouraged meeting and developing a plan (12U grad) parents & Student met w/administrators, student given answers coordinator found new placement registrar helped; student received licensure coordinator worked with instructor to change grade student admitted to doc program; probl for 11 5/16/12 o UG SPED 5/16/12 p UG MDL 6/20/12 q UG SPED commencement student having trouble in field; action plan developed student wrote to UC is Listening re: Tools instructor student having dispositional issues graduation (Masters) certified for graduate 12S faculty checked, were surprised by comments (rec'd A grade) enrolled 12S The complete file for these complaints will be available onsite during the BOE visit. Complaints made to the ombudsman. The University Ombuds indicates that it helps individual students through listening to the complaint, advising the student of options, answering questions about university policies and procedures; facilitating a mutually satisfying agreement or mediating a resolution; or referring to the appropriate university office or individual. The ombuds office supports students in financial concerns, undergraduate grade grievances, course schedule difficulties, academic dishonesty complaints, fee disputes, sexual harassment, discrimination, campus housing concerns, or grievance procedures. The ombuds office is available to students, faculty, staff, alumni, and parents, and typically receives more than 2500 inquiries a year. Due to the confidentiality issues related to the ombuds actions, we are not able to provide further information related to candidates in the unit. www.feedback.uc.edu is an online way to share compliments, complaints, questions, suggestions, and surveys. The information gathered on this web-based questionnaire is sent to the provosts’s office and then provided to the appropriate administrator. Students can request a response or simply complete the form. The student grievance procedures. Undergraduate students may grieve when 1. A student believes that he/she has been subjected to an academic evaluation which is capricious or biased or 2. A student believes he/she has been subjected to other improper treatment. The following procedures appear in the Universities Federal Compliance document: To use these procedures, a student may initiate an informal complaint in the University Ombuds Office (607 Swift Hall) or the college office in which the course is offered no later than the end of the quarter following the quarter in which the activity that gave rise to the complaint occurred. A student registered for cooperative education through the Division of Professional Practice will receive an extension of one quarter upon his/her request. All complaints shall be heard without unnecessary delay. Complaints regarding a course will be in the jurisdiction of the college offering the course. If the course is offered in a different college than the student’s home college or school, the complainant’s college representative will sit as an ad hoc member of the College Grievance Review Committee (CGRC) (see Step 3). Two or more students with the same complaint may join in a group action. A single statement of complaint shall be submitted and processed in the manner described herein for individuals, but all those joining in such a group action must sign the statement. The University Ombuds shall determine whether, in fact, all of the students have the same complaint. If it is found that they do not, they will be divided into two or more subgroups. One individual may represent the entire group but all complainants may be required to meet with the University Ombuds or the CGRC. Step 1 – Informal Resolution. The parties involved must first attempt to resolve the complaint informally. First the student must talk with the faculty member about his/her complaint. A faculty member must be willing to meet with a student for discussion. If the complaint is not resolved, the student must talk with the faculty member’s department or unit head or a college representative designated by the dean, who will attempt to resolve the complaint. If the complaint is not satisfactorily 12 resolved, a student may proceed to Step 2, Mediation, or Step 3, Formal Resolution, no later than the end of the following quarter. Step 2 – Mediation. Mediation shall be requested of and conducted by the Office of the University Ombuds. The University Ombuds (UO) shall consult with the college and shall meet with the individuals separately and/or together to attempt to reach a solution (written) which is agreeable to and signed by all parties to the dispute. All individuals directly involved shall receive a copy of the signed resolution. No written records, other than the final resolution, shall be retained by the UO. Original documents shall be returned to their source or to another site as agreed in the signed resolution. All other notes shall be destroyed. If the complaint is not resolved through mediation, the UO shall immediately notify the chair of the CGRC in the college in which the dispute originated and inform all affected parties in writing. Step 3 – Formal Resolution. Following the receipt of the notification that the complaint was not resolved informally through Mediation (Step 2), the student(s) may file a grievance with the chair of the CGRC. The chair, who is appointed by the college dean, shall schedule a grievance review meeting. The CGRC shall be composed of two faculty selected from a pool of four elected from the faculty of the college, two students from a pool of four selected by the College Tribunal or student government, and the chair. Any party to the complaint may challenge the participation of any committee member on the grounds of conflict of interest. Challenges must be submitted in writing to the chair of CGRC within two (2) days after the parties have been notified of the CGRC composition. If the chair is challenged, the appointing dean shall determine the validity of the challenge and either replace or retain the chair. The challenge must specify reasons that would prevent the individual from being unbiased with respect to the grievance. Any faculty member directly involved in the grievance shall not participate as a member of a CGRC. A student may withdraw a grievance from further consideration at any time by submitting a written statement to the chair of the CGRC. No reason needs to be given for withdrawal of the grievance. Following the grievance review meeting, the CGRC shall issue a report to the college dean. The CGRC’s report shall contain: (1) Relevant information including, but not limited to, documentation of written and oral information presented to the CGRC; (2) Relevant university rules and policies; and (3) Decisions and the reasons therefore. The college dean shall notify both parties in writing of the CGRC’s decision. Either party may appeal the decision of the CGRC in writing to the college dean within 10 days following notification. Grounds for appeal shall be limited to procedural error or new information not available at the time of the hearing. The college dean shall have the authority to accept and implement or modify the decisions of the CGRC. If the grievance alleges capricious or biased academic evaluation and the CGRC finds in favor of the grievant, the college dean may exercise his/her authority to alter the grade. Decisions of the college dean shall be final. Graduate students follow the grievance procedures of the graduate school. The process is described at http://grad.uc.edu/student-life/policy/grievances.html . Evidence of active involvement of faculty in the TI process. The following table describes the active involvement of faculty members in the TI process: Faculty Name Bauer, Anne Role in Initiative Vertical alignment, early field experiences, dispositions, steering committee 13 Breiner, Jon Brydon-Miller, Mary Camp, Emilie Carnahan, Christi Dell, Laura Graden, Janet Gregson, Susan A. Haring, Karen A Haydon, Todd Hord, Casey Johnson, Holly A Dispositions, steering committee Stone soup Vertical alignment, steering committee Embedding field experience Vertical alignment , steering committee Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, dispositions Johnson, Marcus Kohan, Mark Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Kroeger, Stephen Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Laine, Chester H Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Meyer, Helen Palmieri, Maria Schroeder, Sarah Stringfield, Sam Embedded field experiences Steering committee Course design and instructional support for all themes/activities Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Swoboda, Chris Troup, Karen S. Zydney, Janet Embedded signature assessments Standard 3 Requested interviews about field placements and clinical experience with candidates, mentors, district administration, and faculty. These interviews are scheduled. Clarified description of field and clinical experiences. Field and clinical experiences start when the candidate is admitted into the proposed education program and are grouped into three types: 1) initial field experiences, 2) more intensive experiences and 3) Clinical/Student Teaching. Each addresses minimum requirements of each field experience. There is a minimum of 100 total hours for all field experiences and these hours are to be distributed across the entire proposed education program. These experiences are aligned with the Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession. The characteristics of each of these levels of experiences as provided by our programs are presented in this table: Initial Field Experiences 1. Observations 2. All experiences supervised 14 3. Method of earning hours (embedded, course based) 4. Documentation of candidate performance by university supervisors and/or P12 teachers 5. Benchmarks or gateways are clearly defined More intensive Experiences Clinical Experiences or Student Teaching 1. All experiences are supervised-yes, university supervisor and school based mentor teacher 2. Experiences during methods block should be at least 60 hours 3. Additional hours should range between 10-30 hours 4. Must include documentation of how hours were earned 5. Documentation of candidate performance by university supervisors, and/or P12 teachers 6. Documentation that experiences are within the reading core, including AYA and multi-age programs-lesson plans taught by student must have approval of mentor teacher and/or university supervisor 1. All experiences are supervised 2. Minimum of twelve weeks, including at least four consecutive weeks of full-time teaching responsibility (planning, implementing, learning, activities, assessments) 3. Includes a minimum of three face-to-face observations by university supervisors using Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession assessments 4. Includes a minimum of three evaluations by the cooperating teacher aligned with Ohio Standards for the Teaching Profession 5. Additional specific assessments determined by the program (action research, case study, teacher work samples)-Student will be required to complete the TPA A table of the experiences and clock hours for initial licensure and baccalaureate programs is provided here: Program Initial and Undergraduate Teacher Preparation Programs Initial Field Experiences More Intensive Experiences Course Hours Early Childhood Learning Community: Prek Associate/ BSED Completion Program Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Student Teaching 100 Introduction to Education 10 Preschool Practicum 245 Early Childhood Education Pre-K - Third Grade Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Kindergarten Practicum 227+ Introduction to Education 10 Primary Practicum 227+ Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Field Practicum 1 75 Introduction to Education 10 Field Practicum 2 75 Introduction to Field Exp. 15 Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Teaching Reading 75 Introduction to Education 10 FirstField Experience 75 Second Field 75 Middle Childhood Education (may include generalist) Grades 7-12 English/Language Arts Course Hours Clinical/ student teaching Course Hours Internship 200 Student Teaching 300+ Student Teaching 300+ Student Teaching 300+ 15 Grades 7-12 Mathematics Grades 7-12 Science Grades 7-12 Social Studies Multiage Foreign Language (DORMANT) Intervention Specialist (Mild Moderate +Moderate Intense Licenses) Woodrow Wilson Fellows Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Field Experience 75 Student Teaching 300+ Introduction to Education 10 Second Field Experience 75 Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Field Experience 75 Student Teaching 300+ Introduction to Education 10 Second Field Experience 75 Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Field Experience 75 Student Teaching 300+ Introduction to Education 10 Second Field Experience 75 Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Field Experience 75 Student Teaching 300+ Introduction to Education 10 Second Field Experience 75 Intro to Exceptionalities 10 Instructional Strategies 40 Internship Mild/Moderate 300+ Introduction to Education 10 Teaching Associate Mild/Moderate 90 Internship Moderate Intense 300+ Assessment and Curriculum Planning 30 Teaching Associate Moderate Intense 90 Summer Field Experience 75 Clinical Experience I 200+ Clinical Experience II 300+ Field and clinical experience for advanced programs and other school personnel are presented in this table: Program Course Gifted Endorsement Early Childhood Generalist Grades 4-5 Practicum Field Experience Curriculum and Instruction Field Experience (collecting data, analyzing impact on student learning) Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Superintendent Practicum Clinical Internship Pre-placement Placement Clinical Internship Pre-placement Placement Internship Action research project Practica Assessment, Instruction, and Practicum I Assessment, Instruction, Practicum II Principal Special Education Second License Special Education Advanced School Psychology Literacy M. Ed. and Reading Endorsement Teacher Leader Practicum Hours 75 20 75+ 75 approximately 20 300+ approximately 20 300+ 75+ 75+ 400+ 100 clock hours at three grade bands 75+ 16 Selection of Clinical Faculty. Potential clinical faculty members are brought to the attention of the programs a variety of ways. Four years ago, when we striving to increase the number of placements in Cincinnati Public Schools, Hamilton, Newport, and Covington (at times referred to as the urban core) field coordinators of each of the programs met with principals, described the program, and identified potential clinical faculty members who met the criteria of appropriate licensure, at least three years of successful experience, and graduate degrees. In addition, members of the Partnership Panel were asked to nominate mentors who they felt would be appropriate and met the criteria. These activities, as well as recommendations from current successful mentors, have allowed us to generate a pool that exceeds the diversity represented among teachers in Ohio. Placements and mentors are evaluated by both university supervisors and candidates, and these data are used to identify mentors who are not meeting the expectation of being strong school professionals. Clinical Faculty Member Participation in the Transformation Initiative Our current clinical faculty participants in the Transformation Initiative are school faculty members with whom we have had ongoing relationships for several years. These partnerships began during the Cincinnati Initiative for Teacher Education, which implemented a five-year initial teacher preparation program at the University of Cincinnati in response to participation in the Holmes Partnership. At that time Cincinnati Public Schools identified liaisons in each of our Professional Practice Schools. Though the model was dissembled due to funding and decreasing enrollments, the relationships continued. Strong relationships vary by program and participating faculty members. Working person-to-person has the advantage of engaged school faculty members as true partners on behalf of the students, candidates, and school. However, we have had some school partnerships fade away as individual faculty members leave. We have made consistent efforts in professional development of our partners. A specific question was posed as to whether school faculty members have the skills to measure student learning and mentor candidates in that effort. An example of special education’s response is a recent in-service with mentor teachers and their candidates to insure that all participants understood the data collection, single case design, and data-based decision making in which the candidates must participate. Activities of the Center for Hope and Justice also have included working with the Freedom Center and Freedom Writers Foundation to make sure university and school faculty members are “on the same page” related to measuring impact on student learning. In that we are in the early stages of our Transformation Initiative, we anticipate that the number and strength of partnerships will continue to grow. Examples of efforts to prepare mentors and supervisors are provided in the Evidence Addendum page 10. Standard 4 There are no clearly defined TI diversity-related efforts for advanced programs. At this time the transformation initiative is primarily an initial program effort. A large percent of school-based faculty members’ race/ethnicity was reported as unknown. Our initial data collection system of mentor (school-based faculty) qualifications did not include race. The demographics form provided by NCATE related to faculty demographics indicates “include schoolbased faculty if possible”. The data reported were those provided voluntarily in response to a request to university supervisors. Recognizing the issues related to this incomplete data and our challenges to 17 provide a diverse experience for our candidates, we revised our data collection system and implemented a direct survey at the end of Fall 2011. These are the data from the most recent survey: Ohio general population: 11.5% black, 1.9 Latino, Asian <1% Hamilton County Public School Teacher Statistics: 93.8% white, 5% black. .6% Latino, .1% American Indian or Alaskan Native, .2% multiracial or did not specify Mentor Teacher Demographics Response 26 28 % 8% 9% 7-12 Mathematics 7-12 Sciences Multiage Foreign Language Early Childhood Education Middle Level Education Intervention Specialist: Mild/Moderate 29 26 8 31 23 43 9% 8% 3% 10% 7% 14% Intervention Specialist: Moderate/Intense Multiage Art Multiage Music Elementary Education Other 24 21 0 82 61 8% 7% 0% 27% 20% 238 54 10 3 78% 18% 3% 1% 245 81% Additional graduate work Doctorate Total Please indicate all that apply to you: National Board Certified Resident Educator Mentor or District Mentor 52 5 302 17% 2% 100% 19 48 14% 35% Teacher Leader Endorsement Other awards or recognitions Race: Latino of any race Black or African American American Indian or Alaskan Native 32 75 23% 54% 3 33 0 1% 11% 0% Asian Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander White 5 0 263 2% 0% 87% 7-12 English/Language Arts 7-12 Social Studies License: Professional Permanent (certificate) Lead Professional Educator Senior Professional Educator Education: Masters 18 Total 304 100% Updated data related to race and ethnicity of advanced candidates. Our data warehouse has recently recoded student data in view of the new federal guidelines. We still have a number of candidates who prefer to indicate “unknown.” In that this is self-reported data it is voluntary, and we have no way to clarify or change the “unknown” race and ethnicity. With the recoding, and pulling data from the 20112012 academic year, we were able to derive these data for our advanced candidates: Race/Ethnicity American Indian or Alaskan Native Asian-Pacific Islander Black, Non-Hispanic Latino Non-Resident Alien White Mixed Race Unknown # 1 5 68 11 3 539 6 68 701 Percent 0.14% 0.71% 9.70% 1.60% 0.40% 76.90% .85% 9.70% Specifics for schools used for field and clinical experiences. Because of our large number of field experiences, we had initially provided the NCATE required data at the district level in table 4.4.g. In an effort to provide more thorough evidence, however, we have provided data for the initial program which indicates the number of schools used in each district and the number of placements in those schools. We have also provided the individual school data with number of placements for schools in Hamilton County, where all but a few placements are made. Advanced program placements are used by only one or two students each year, so we did not break down those data in that way. Demographics of school districts used for clinical practice are included in 4.4g. Data related to specific schools, which, as a group, comprise over 98% of our field experiences are provided in the Evidence Addendum beginning on page 10. Other districts/ sites are used rarely. Opportunities for initial and advanced candidates to work together on projects and committees related to education and content areas. The “acceptable” rubric states: Candidates engage in professional education experiences in conventional and distance learning programs with male and female candidates from different socioeconomic groups, and at least two ethnic/racial groups. They work together on committees and education projects related to education and the content areas. Affirmation of the value of diversity is shown through good-faith efforts the unit makes to increase or maintain pool of candidates, both male and female, from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic/racial groups.” The “target” rubric states, Candidates engage in professional education experiences in conventional and distance learning programs with candidates from the broad range of diverse groups. The active participation of candidates from diverse cultures and with different experiences is solicited, valued, and promoted in classes, field experiences, and clinical practice. Candidates reflect on and analyze these experiences in ways that enhance their development and growth as professionals. “In our review of our efforts, we were unable to identify aspects of the rubric that required initial and advanced candidates to work together on projects and committees. Initial and advanced candidates do collaborate in the Middle Childhood Education Society and the Council for Exceptional Children. They 19 work together in field experiences when assigned as members of the group. Explicit activities are not planned to force collaboration among initial and advanced candidates. Are initial candidates all required to take both Introduction to Education and Introduction to Exceptionalities? Yes. Curriculum components and experiences of the Transformation Initiative that are related to diversity. The following curriculum components and experiences are related to diversity: Early field experiences in all initial programs that occur in urban settings. Though data are not yet available, candidates in the Introduction to Education class complete a course portfolio reflecting on their efforts, data are not yet available. In the Introduction to Exceptionalities class, candidates respond to their early field experiences by engaging in a pre and post test of perceptions of disabilities. Data are currently being collected. Embedded field experiences in large urban high poverty schools that provide faculty members the opportunity to model interacting with administrators, teachers, and students of different ethnicity, race, socioeconomic gender, exceptionalities, and language. In these experiences, candidates complete specific tasks to ease their movement into the school environment. These experiences include a reading survey, a motivation to read survey, and an analysis of student work. These assessments were piloted last year, and data collection is currently taking place. The general outcome of the 4-year Vertical Alignment of a Teacher Education Program to develop a diversity repertoire is to prepare teachers to acknowledge, affirm, and practice culturally and individually responsive pedagogy. This project is grounded in our desire to teach our candidates to recognize what Milner (2010) refers to as an opportunity gap rather than an achievement gap. As a result of this project, teacher candidates will: Recognize and respond to a diversity repertoire in their teaching and writing • Recognize difference between intent and impact • Develop a shared vision, motivation, knowledge, and community of practice • Develop a vision of learning on a continuum (ex. accessing the environment) and avoiding labels (ex. disability as perception) • Using students’ funds of knowledge to expand knowledge and skills • See people first As a direct object of this project teacher candidates will engage in consistent and critical activities to identify opportunity gaps and address them in the pedagogy across all four years of their coursework. The process measure is the development of a diversity repertoire, which will be monitored through both formative and summative assessments. Baseline data from the open ended prompt. Rather than analyzing data from a discussion board prompt responding to a quote related to “color- blindness”, these responses were used to generate a rubric for “writing about other peoples’ children.” This rubric will be piloted during the 2012-2013 academic year. Focused assessment data. Data are also now available on the pilot related to our detailed or focused dispositions assessment, which assists supervisors, mentor teachers, and candidates’ peers in identifying and developing measurable behaviors identified in the literature as consistent with effective teaching in 20 large, urban, high poverty settings. This assessment is now institutionalized in all initial programs. Pilot data are available in the Evidence Addendum beginning on page 21. Reflections related to the work at Hughes STEM High School. The report of the progress of the Hughes STEM Literacy Initiative are provided in the Evidence Addendum beginning on page 26. Standard 5 Faculty information form. These data are available Evidence addendum on beginning on page 36 and is posted at www.uc.edu/cech-accreditation Mentor and university supervisor training. In order to insure uniformity of information, all mentors, university supervisors, and candidates use the same program handbook which is available on the program field assessment sites. Any additional information developed during the semester are also posted on the www.cech.uc.edu/oaci site. A full series of the resources and workshops offered to mentors and supervisors is provided in the evidence addendum beginning on page 10. Preparation related to the Teacher Performance Assessment. The Teacher Performance assessment was piloted in 2010-2011 and field tested in 2011-2012. During that time the Teacher Performance Assessment coordinator, Dr. Chet Laine, met with each program to support their understanding and implementation of the Teacher Performance Assessment. In addition, materials are provided to each teacher related to the assessment and the level of support that may be provided. Dr. Laine has also made presentations to the University Council for Educator Preparation. Materials shared during those workshops and meetings are provided in the evidence addendum beginning page 73. Encouraging professional development. The statement “The unit has policies and practices that encourage all professional education faculty to be continuous learners” is found in “target” rather than “acceptable” language. Though this request for evidence exceeds “acceptable” expectations, professional development is indeed encouraged on all levels. At the university level, a “faculty development one-stop” site is provided (http://www.uc.edu/facdev/home.aspx). Three fellows of the university’s Academy of Fellows of Teaching and Learning are professional education faculty (Drs. Cheri Williams, Linda Plevyak, and Annie Bauer). These faculty members mentor new faculty in teaching. In addition, the Collective Bargaining Agreement Article 24.3 states that “Each college and library system will develop a process for planning and implementing annual Faculty development programs.” The university, by AAUP contract, is also required to encourage participation in activities of professional organizations and requires policies for reimbursement of travel and assistance from other sources beyond the unit’s travel budget. Section 24. 7 states: The University shall provide $660,000 for each of the three years of this contract to fund professional development” which are awarded through an application process. Each academic unit has additional resources to encourage professional development, such as the College of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Service’s Dean’s incentive fund, which distributes $100 for professional development for each presentation and refereed article up to $300 per academic year. Faculty Evaluation System. The Offsite report requested evidence to determine “a) that faculty reflection is meaningful part of the evaluation system (b) how extensively used is the peer observation system; (c) the ability of faculty to model best practices in instruction including those related to the TI part of the evaluation system, and (d) the results of faculty evaluation used to design professional 21 learning of faculty. “ At the acceptable le level, the rubric only states “the unit conducts systematic and comprehension evaluations of faculty reaching performance to enhance the competence and intellectual vitality of the professional education faculty. Evaluations of professional education faculty are used to improve the faculty’s teaching, scholarship, and service.” At the target level the rubric states, “The unit’s systematic and comprehensive evaluation system includes regular and comprehensive reviews of the professional education faculty’s teaching, scholarship, service, collaboration with the professional community, and leadership in the institution and profession.” All faculty evaluation is constrained by the AAUP-UC Collective Bargaining Agreement Contract, and additional requirements on faculty members is not possible. The contractual annual faculty evaluation states: “Following the directive of H.B. 1521, the Annual Performance Review is a yearly evaluation of each faculty member’s work performance in relation to the unit’s mission statement and goals as well as its established workload policy. Developmental in nature, the annual review is used to promote professional growth and guide faculty members in their subsequent work responsibilities, interests, and activities. Following the contractual understandings of the university and UC’s chapter of the AAUP, the review serves as an opportunity for the unit head and faculty member to determine the faculty member’s work responsibilities in relation to the faculty member’s interests and activities. The review is further used as a venue for the unit head and faculty member to discuss changes in the interests and skills of the faculty member, and serves as an opportunity to make adjustments to faculty members’ contributions to the unit. It is also used to prompt discussion of the resources needed by faculty members to develop or maintain skills, interests, research, scholarship, while also presenting accomplishments from the year prior. Thus, the annual performance review is for anticipating the next year and a review of the past. It also allows for the accumulation of evidence for the performance of the faculty member who may be tenured but has not achieved all promotions available. With oversight by the unit head, the Annual Performance Review is an official document that works best when it is an instrument for faculty and unit development, and thus is prepared in tandem between faculty member and unit administration. Written by the unit head or delegated to an appropriate designee, differing opinions about the content of the review are included in the summary statement, a copy of which is given to the faculty member while the original is placed in the faculty member’s personnel file. The format the unit utilizes addresses teaching, advising, educational innovation, research and creative activity, university professional, and public service, and other accomplishments pertinent to the mission. At present, faculty members are expected to turn in an annual reflection of their work for the preceding year along with a Workload Plan for the subsequent year that has been filled out jointly by the School Director (who determines the teaching load). Both documents are due on June 30 of the academic year. The School Director then reviews the faculty member’s reflection and evaluates their progress based on the Unit’s mission and goals, and the faculty member’s Workload Plan for that year. The School Director then sends the faculty member their evaluation. If there are errors of fact, those are changed (such as the number of courses taught, the evaluation data, etc). The faculty member is invited to respond to the evaluation and upon receiving the signed document back from the faculty member, the School Director attaches the evaluation to the Annual Reflection, which then becomes part of the faculty member’s personnel file. “ 22 Standard 6 Unit governance. At the University of Cincinnati, the following colleges are engaged in educator preparation: Arts and Sciences Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services (School of Education and School of Human Services) College/Conservatory of Music Design, Art, Architecture, and Planning In that educator preparation cuts across colleges, the provost serves as the unit head. In order to provide shared governance among the various colleges, and to include candidates and members of the professional community, the University Council of Educator Preparation was formed. This group makes unit decisions under the charge given the group by the Provost. It is a provostal council and informs the provost (Lawrence Johnson, Ph. D.) regarding the efforts of the unit. The dean of the College of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services is charged by the University Council for Educator Preparation and the provost with managing the accreditation process, but has been judged inappropriate to serve as the head a cross-college effort. Though most educator preparation programs are housed in the School of Education within the College of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services, the number of programs in the School of Human Services makes naming the director of the School of Education as the head of the unit inappropriate as well. The two bodies that are most conversant regarding the Transformation Initiative are (a) the University Council for Educator Preparation and (b) the Transformation Initiative Steering Committee, headed by Associate Dean Holly Johnson, who manages innovation and outreach for the College of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services. The Office of Assessment and Continuous Improvement, led by Dr. James Vondrell, is responsible for the day to day implementation of the assessment system, field and clinical experiences, and the licensure process. The Office of Assessment and Continuous Improvement is part of the Office of the Dean, and the way in which the dean insures that the accreditation process is managed. The Transformation Initiative and Standard 6. The relationship of the Transformation Initiative to Standard 6 was described as “troublesome.” It is the contention of the Transformation Initiative Steering Committee that this is true in the Transformation Initiative efforts are not directed to modify, transform, or have a direct impact on the unit governance and resources. The Transformation Initiative effort has not involved additional funding or governance structures. The University Council for Educator Preparation endorsed the Transformation Initiative for submission to NCATE, and has been the body to review and revise the conceptual framework and assessment systems as well. As such, there is knowledge and guidance provided to the Transformation Initiative, but at this time the initiative does not change the way in which the unit is governed nor the way in which resources are distributed. Interviews have been scheduled with the Provost, members of the University Council on Teacher Preparation, and the Transformation Initiative Steering Committee. In addition, tours of the renovated space will be scheduled Minutes of the University Council for Educator Preparation are available in the Evidence Addendum beginning on page 61. 23 Clerical, advisement, and IT resources in the unit. Rather than clerical assistance, the unit uses “academic directors” to manage procedures and practices. For example, an academic director manages the licensure process and another oversees distance learning programs. Each program has an assistant academic direct who manages monitoring student progress, course orders, data from assessments, and other tasks that may emerge. In terms of advisement, we have set up interviews with the director of the Student Services Center. In terms of information technology, a fully staffed IT office is available in Teachers College. At the university level, UCIT provides a helpline, walk in computer support, software support, and manages Blackboard. There is a 24/7 computer lab in the Langsam Library, and additional computer labs in Teachers College with both PC and Macs available. Each classroom in Teachers College (and throughout the university) has an instructor station with Internet access, a document projector, screen, and projector. SMART boards are being installed according to a university-wide plan, and several are in place in Teachers College. Transformation Initiative Summary Faculty engaged in the Transformation Initiative. Data available for the addendum indicate that there are 74 full time professional education faculty members. Of these 23 (31.1%) are activity engaged in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the Transformation Initiative. This does not take into account the individuals who only implement program and curricular changes (university supervisors of early field experiences, instructors in the vertically aligned diversity coursework, graduate assistants engaged in data collection and analysis). Faculty members and their participation efforts are provided here: Faculty Name Bauer, Anne Breiner, Jon Brydon-Miller, Mary Camp, Emilie Carnahan, Christi Dell, Laura Graden, Janet Gregson, Susan A. Haring, Karen A Haydon, Todd Hord, Casey Johnson, Holly A Role in Initiative Vertical alignment, early field experiences, dispositions, steering committee Dispositions, steering committee Stone soup Vertical alignment, steering committee Embedding field experience Vertical alignment , steering committee Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, dispositions Johnson, Marcus Kohan, Mark Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Kroeger, Stephen Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Laine, Chester H Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Meyer, Helen Embedded field experiences 24 Palmieri, Maria Schroeder, Sarah Stringfield, Sam Swoboda, Chris Troup, Karen S. Zydney, Janet Steering committee Course design and instructional support for all themes/activities Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences Impact on student learning Vertical alignment, steering committee, impact on student learning, early field experiences, dispositions Embedded signature assessments Publications and presentations that emerged from the transformation initiative are listed here: Embury, D.C. & Kroeger, S. D. (2012). Let's ask the kids: Consumer constructions of co-teaching. International Journal of Special Education, 27 (3). Israel, M., Carnahan, C., Snyder, K. & Williamson, P. (accepted). Supporting new teachers of students with significant disabilities through virtual coaching: A proposed model. Remedial and Special Education. Johnson, H., Kohan, M., Laine, C., & Meyer, H. (2012, February). Exploring four exemplary educational partnerships for democracy and justice. Realizing imagined partnerships: Working towards a common goal. AACTE Annual Convention. Chicago, Illinois. Killham, J., Kohan, M., & EDST 201 students. (2012, May). A dangerous game for pre-service teachers: Playing for transformation through arts-based inquiry. International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry. Urbana-Champaign, Illinois Kohan, M. & Hughes High School Freedom Writers. (September, 2011). Cincinnati freedom writers project possibilities. Mayerson Student Service & Leadership Conference. Cincinnati, Ohio. Kohan, M., Laine, C., & Hughes High School Freedom Writers (2012, April). Leading for respect & diversity through the Cincinnati freedom writers’ project. University of Cincinnati Annual Diversity Conference. Cincinnati, Ohio. Kroeger, S., Brydon-Miller, M., Laine, C., Troup, K., Haring, K., Johnson, H. (04/15/2009). Stone Soup: Using Action Research to Create Opportunities for Program Integration in Teacher Education. American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA. Kroeger, S., Embury, D., Cooper, A., Brydon-Miller, M., Laine, C., & Johnson, H. (2012Stone soup: using co-teaching and Photovoice to support inclusive education, Educational Action Research, 20:2, 183-200 Laine, C., Kohan, M., and Hughes High School Freedom Writers. (2011, November). Reading the past and writing the future: An urban literacy initiative. NCTE Annual Convention. Chicago, Illinois. Kroeger, S. D., Laine, C. H. (2010).Pre-service English teachers and special educators: Opportunities and barriers to collaboration. In Hruby, G., Heron-Hruby, A., &Eakle, J. (Eds.) Exploring Literacy and 25 Collaboration in the 21st Century. American Reading Forum Online Yearbook.http://www.americanreadingforum.org/ Kroeger, S. D., Embury, D. C., Cooper, A., Brydon-Miller, M., Laine, C., & Johnson, H. (2012). Stone Soup: Using co-teaching and Photovoice to support inclusive education. Educational Action Research, 20(2), 183-200. Laine, C., Bauer, A., Johnson, H., Kroeger, S., Troup, K., & Meyer, H. (2010). From reaction to reflection: Program commitment to learning for all. In P.C. Murrell, Jr., M. Diez, S. Feiman-Nemser, & D. L. Schussler. (Eds.), Teaching as a Moral Practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 73-93. Kroger, S., Laine, C., & Troup, H. (2010) Teacher Education Division Conference, St. Louis, MO. Informing Program Transformation through Co-Teaching. Collaboration and service opportunities emerging from the initiative. Several collaboration and service opportunities have emerged from the initiative. Our strongest collaborations are with the Cincinnati Public Schools, particularly Hughes STEM High School. In this effort we have collaborated with and provided professional development to school faculty, specific interventions to students, and technology in terms of a pilot program using iPads with students with intense educational needs. We have also collaborated with Children’s Hospital Medical Center to provide educational and social skills interventions with adolescents with sickle cell disease. Through our collaborations, candidates have worked with inner city school based Girl Scout programs, Special Olympics, Kids Café, Homework Help, chaperoning at Hughes’ pep rallies, games, and dances, and managing curriculum area book rooms. Resources, governance, and technology accomplishments and needs. At this point in our efforts we have not identified any changes in resources, governance, or technology that have either occurred or emerged as needs.