a review on venture capital

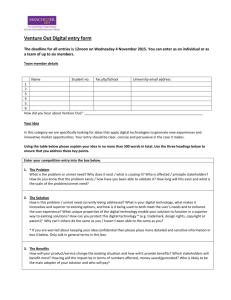

advertisement